1. Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the most prevalent chronic metabolic disorders worldwide, with a steadily rising incidence and serious cardiovascular consequences. Among these complications, coronary artery disease (CAD) holds particular significance as it remains the leading cause of mortality in patients with diabetes (1). The underlying pathophysiology of CAD is characterized by the progressive accumulation of lipids, inflammatory cells, and fibrotic tissue within the walls of coronary arteries, resulting in reduced myocardial perfusion and the development of stable or unstable angina (2).

Diabetes markedly accelerates the atherosclerotic process. Consequently, patients with T2DM not only face a higher risk of developing CAD but also typically exhibit more extensive and severe coronary involvement compared to non-diabetic individuals (3).

In recent years, the Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI), which is calculated as the ratio of ankle systolic blood pressure to brachial systolic blood pressure, has emerged as a simple, non-invasive tool for detecting peripheral artery disease (PAD). An ABI value < 0.9 is generally indicative of significant peripheral atherosclerosis (4). Growing evidence, however, suggests that a reduced ABI may reflect systemic atherosclerosis, including involvement of the coronary arteries. Several studies have reported that diabetic patients with lower ABI values tend to have more severe and extensive coronary atherosclerosis, as confirmed by coronary angiography (5, 6). These observations raise the possibility that ABI could serve as a surrogate or complementary marker for estimating the coronary atherosclerotic burden in patients with diabetes (7, 8).

Despite these findings, results from existing studies have been inconsistent. While some investigations have demonstrated a significant association between ABI and the severity or extent of coronary atherosclerosis, others have failed to confirm such a relationship. Discrepancies may arise from differences in atherosclerosis assessment methods (conventional angiography vs. CT angiography), heterogeneity in study populations regarding glycemic control, the presence or absence of symptomatic CAD, and concomitant cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia. Moreover, many prior studies did not specifically focus on diabetic patients or extrapolated findings from mixed populations, despite the fact that diabetes itself can independently influence both ABI values and the progression of atherosclerosis (9-15).

Thus, it remains unclear whether the ABI can independently and accurately predict the severity and extent of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with T2DM presenting with stable angina pectoris.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to address existing gaps in the literature, resolve prior conflicting results, and provide robust evidence that may enhance cardiovascular risk assessment and prognostic evaluation in patients with T2DM.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between March 2022 and March 2024 at Shohadaye Tajrish and Masih Daneshvari hospitals in Tehran, Iran. We enrolled 420 consecutive adult patients aged 18 - 70 years who had confirmed T2DM, presented with chronic stable angina pectoris, and had at least one coronary artery stenosis ≥ 50% or greater. All patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography as part of their routine clinical care.

Patients with known PAD, history of lower-limb revascularization or amputation, acute coronary syndromes, age above 70 years, or severe comorbidities that could affect ABI measurement were excluded. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1404.180)

3.2. Patient Evaluation and Data Collection

All patients underwent diagnostic coronary angiography performed by experienced interventional cardiologists. The extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis were quantitatively assessed using the SYNTAX score. To ensure consistency and reproducibility, SYNTAX score calculation and interpretation for the entire cohort were performed by a single experienced member of the research team.

The SYNTAX score was derived by assigning points to each significant coronary lesion (≥ 50% diameter stenosis) located in vessels ≥ 1.5 mm in diameter, according to the American Heart Association 16-segment coronary tree classification. Each segment was first given a baseline weight ranging from 0.5 (small distal branches) to 5.0 (left main coronary artery) or 3.5 (proximal left anterior descending artery). A multiplication factor of 2 was applied for non-occlusive stenoses (50 - 99%) and a factor of 5 for total occlusions. Additional points (+1 for each feature) were added for total occlusion > 3 months duration, blunt stump, bridging collaterals, first visible segment beyond the occlusion, and side branches ≥ 1.5 mm in diameter. Lesions in vessels < 1.5 mm or stenoses < 50% were not scored. The final SYNTAX score was automatically computed by the algorithm. Patients were subsequently categorized as low (< 18), intermediate (18 - 27), or high (> 27) SYNTAX score for descriptive and subgroup analyses. Following coronary angiography and SYNTAX score calculation, demographic characteristics and cardiovascular risk factors were systematically recorded from electronic medical records and patient interviews using a standardized case report form.

The ABI was measured in all patients on the day immediately following angiography during the same hospitalization, ensuring no loss to follow-up; measurements were performed by a single trained operator using a validated automated device in accordance with international guidelines. Systolic blood pressures were obtained simultaneously in both arms and ankles, and the patient’s ABI was defined as the lower of the two leg indices (higher ankle pressure divided by higher brachial pressure). The ABI values were classified as severe PAD (< 0.50), moderate (0.50 - 0.69), mild (0.70 - 0.89), normal (0.90 - 1.40), or suggestive of medial arterial calcification (> 1.40), with values ≤ 0.90 or > 1.40 considered abnormal for primary comparative analyses.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Quantitative variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD), and qualitative variables were reported as frequency and percentage. To determine differences in qualitative factors between the compared groups, the chi-square (χ2) test was used, and for quantitative variables, the paired t-test was employed. Additionally, to compare more than two means, the ANOVA test was used. The association between ABI and the severity and extent of coronary atherosclerosis was evaluated using correlation analysis. Multivariable regression analysis was performed to assess the independent association between ABI and coronary atherosclerosis after adjusting for potential confounding factors. A P-value of 0.05 was considered the level of statistical significance.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 420 patients with T2DM and stable angina were included in the analysis. The age range of patients was 39 - 69 years. Abnormal ABI (≤ 0.90 or > 1.40) was present in 97 patients (23.1%). Patients with abnormal ABI were significantly older (64.05 ± 5.77 vs. 57.53 ± 6.96 years, P < 0.0001), more frequently male (47.4% vs. 66.3%, P = 0.001), had a higher prevalence of smoking history (54.6% vs. 27.9%, P < 0.0001), and hypertension (53.6% vs. 38.4%, P = 0.01), and exhibited poorer glycemic control as reflected by higher HbA1c levels (7.58 ± 0.75% vs. 7.18 ± 0.64%, P < 0.0001). The mean SYNTAX score was markedly higher in the abnormal-ABI group (20.08 ± 7.63 vs. 12.19 ± 6.13, P < 0.0001), indicating substantially greater severity and extent of coronary atherosclerosis (Table 1).

| Parameters | Total (N = 420) | Normal ABI (N = 323) | Abnormal ABI (N = 97) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 260 (61.9) | 214 (66.3) | 46 (47.4) | 0.001 |

| Smoking history | 143 (34) | 90 (27.9) | 53 (54.6) | 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 25 | 321 (76.4) | 245 (75.9) | 76 (78.4) | 0.39 |

| 25 - 30 | 74 (17.6) | 56 (17.3) | 18 (18.6) | - |

| > 30 | 25 (6) | 22 (6.8) | 3 (3.1) | - |

| Mean ± SD | 23.62 ± 3.65 | 23.30 ± 3.69 | 23.34 ± 3.53 | 0.39 |

| Hypertension | 176 (41.9) | 124 (38.4) | 52 (53.6) | 0.01 |

| CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m2) | 37 (8.8) | 30 (9.3) | 7 (7.2) | 0.68 |

| LDL (> 55 mg/dL) | 351 (83.6) | 272 (84.2) | 79 (81.4) | 0.53 |

| ABI | ||||

| 0.9 - 1.4 (normal) | 323 (76.9) | 323 (100) | - | - |

| 0.7 - 0.9 | 38 (9) | - | 38 (39.2) | - |

| 0.5 - 0.7 | 34 (8.1) | - | 34 (35.1) | - |

| < 0.5 | 17 (4) | - | 17 (17.5) | - |

| > 1.4 | 8 (1.9) | - | 8 (8.2) | - |

| Mean ± SD | 0.94 ± 0.17 | 1.01 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.20 | 0.0001 |

| Age (y) | 59.04 ± 7.24 | 57.53 ± 6.96 | 64.05 ± 5.77 | 0.0001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.27 ± 0.68 | 7.18 ± 0.64 | 7.58 ± 0.75 | 0.0001 |

| FBS (mg/dL) | 180.3 ± 40.66 | 179.11 ± 41.58 | 184.23 ± 37.43 | 0.27 |

| SYNTAX score | 14.01 ± 7.30 | 12.19 ± 6.13 | 20.08 ± 7.63 | 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

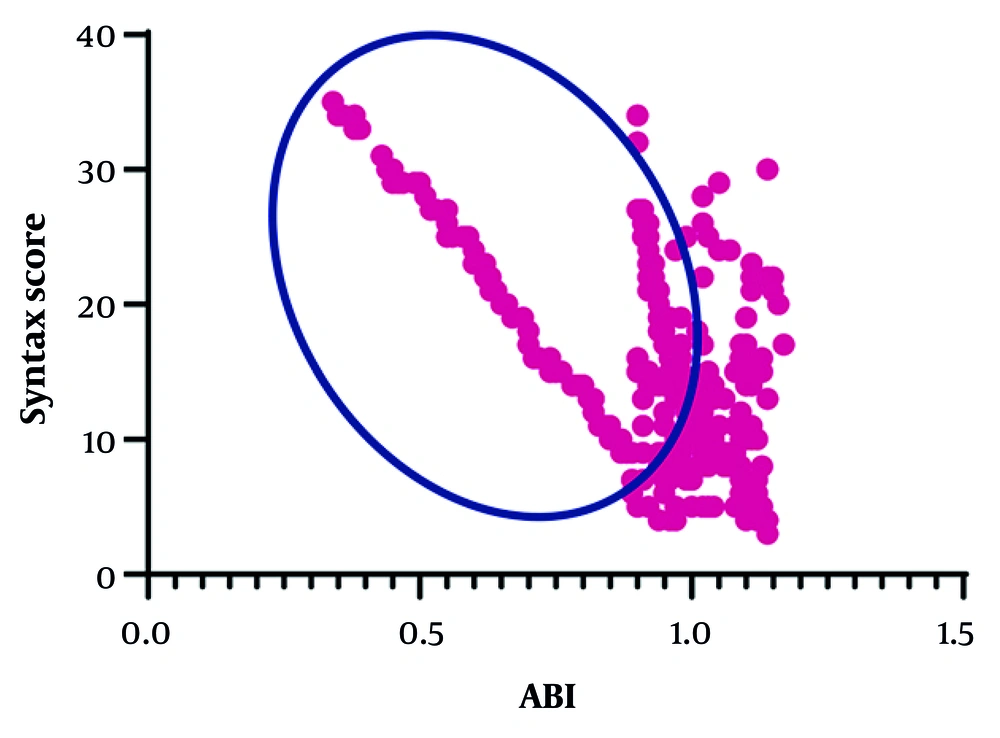

4.2. Correlation Between Ankle-Brachial Index Values and SYNTAX Score

The correlation between ABI and SYNTAX score was evaluated in the entire cohort and in the subgroup with abnormal ABI. A strong inverse correlation was observed between ABI values and SYNTAX score in the overall study population (R = -0.677, P < 0.0001). This negative relationship was even slightly stronger among the subgroup of patients with abnormal ABI (R = -0.685, P < 0.0001), indicating that lower ABI values were associated with progressively higher degrees of coronary atherosclerotic burden (Figure 1).

4.3. Comparison of SYNTAX Score Across Different Ankle-Brachial Index Categories

When patients were stratified according to ABI categories, a highly significant difference in the severity of coronary atherosclerosis was observed (overall P < 0.0001). As shown in Table 2, patients with normal ABI (0.9 - 1.4) had the lowest mean SYNTAX score of 12.19 ± 6.13. In contrast, those with ABI 0.7 - 0.9 exhibited a mean SYNTAX score of 18.94 ± 7.13, patients with ABI 0.5 - 0.7 had a mean score of 19.97 ± 9.02, and individuals with ABI < 0.5 showed the highest mean score among the low-ABI groups at 22.00 ± 7.05. Patients with ABI > 1.4, suggestive of medial arterial calcification, also demonstrated a substantially elevated mean SYNTAX score of 21.87 ± 3.68, comparable to the most severe PAD categories (Table 2).

| Category | SYNTAX Score | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| ABI | 0.0001 | |

| 0.9 - 1.4 | 12.19 ± 6.13 | |

| 0.7 - 0.9 | 18.94 ± 7.13 | |

| 0.5 - 0.7 | 19.97 ± 9.02 | |

| < 0.5 | 22.00 ± 7.05 | |

| > 1.4 | 21.87 ± 3.68 |

Abbreviation: ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

4.4. Independent Predictors of Coronary Atherosclerotic Burden

Multivariable linear regression analysis was performed to assess the predictive value of ABI for the extent of atherosclerosis alongside other variables. Lower ABI emerged as the strongest independent predictor of higher SYNTAX score (standardized β = -0.646, t = -16.68, P < 0.0001, 95% CI: -29.801 to -23.517). Additional independent predictors included hypertension (β = 0.09, P = 0.017), higher HbA1c (β = 0.077, P = 0.034), and LDL > 55 mg/dL (β = -0.103, P = 0.009), while age, male gender, smoking, BMI, chronic kidney disease, and fasting blood glucose did not reach statistical significance in the fully adjusted model (Table 3).

| Variables | Beta | t | P-Value | Lower-Upper Bound (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 0.11 | 0.301 | 0.764 | -0.119 - 0.162 |

| CKD | 0.045 | 1.143 | 0.254 | -0.84 - 3.172 |

| Smoking | 0.072 | 1.822 | 0.069 | -0.087 - 2.298 |

| Male gender | -0.063 | -1.597 | 0.111 | -2.1 - 0.218 |

| LDL (> 55 mg/dL) | -0.103 | -2.624 | 0.009 | -3.565 - -0.511 |

| Hypertension | 0.09 | 2.389 | 0.017 | 0.236 - 2.425 |

| Age | -0.053 | -1.45 | 0.148 | -0.127 - 0.019 |

| HbA1c | 0.077 | 2.13 | 0.034 | 0.063 - 1.581 |

| FBS | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 1.000 | -0.013 - 0.013 |

| ABI | -0.646 | -16.68 | 0.0001 | -29.801 - -23.517 |

Abbreviation: ABI, Ankle-Brachial Index.

5. Discussion

In this study of patients with T2DM undergoing coronary angiography for stable angina, abnormal ABI was observed in approximately 23.1% of cases. Patients with abnormal ABI exhibited significant differences in gender, smoking history, hypertension, age, HbA1c, and SYNTAX score compared with those having normal ABI. A strong inverse correlation was found between ABI values and SYNTAX score across the entire cohort and particularly in the subgroup with abnormal ABI, indicating that lower ABI was associated with greater severity and extent of coronary atherosclerosis. Multivariable regression analysis identified elevated LDL, hypertension, higher HbA1c, and lower ABI as independent predictors of higher SYNTAX score.

Our finding of a strong inverse correlation between ABI and SYNTAX score is consistent with numerous previous reports. Several studies have demonstrated that low ABI (typically ≤ 0.90) is associated with greater severity and complexity of CAD, including higher SYNTAX scores (16-18). The biological plausibility is clear: Reduced ABI reflects increased systemic atherosclerotic burden and PAD, which frequently coexists with more extensive coronary involvement (19). In diabetic populations, chronic hyperglycemia accelerates endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and atherosclerotic progression, further strengthening this relationship (16, 20).

The independent predictive roles of elevated LDL, hypertension, and HbA1c align with established evidence. These traditional risk factors promote plaque formation and lesion complexity, and their persistent influence despite adjustment confirms their central importance in diabetic coronary atherosclerosis (19-21). The addition of ABI — a simple peripheral vascular marker — to these metabolic and hemodynamic parameters provides a more comprehensive estimation of overall atherosclerotic burden.

Recent studies specifically examining the ABI-SYNTAX relationship have reported similar findings. For example, Petracco et al. observed a correlation between low ABI and higher SYNTAX scores in patients with acute coronary syndromes (17), while Aly et al. reported a significant negative correlation (R ≈ -0.48) (16). Studies from diverse geographic regions (India, Pakistan, and Europe) have consistently linked lower ABI with increased CAD severity or complexity (22, 23), supporting the generalizability of our results.

Despite overall consistency, heterogeneity in the strength of association exists across studies. Differences may arise from variations in ABI cutoff values, patient populations (stable angina vs. acute coronary syndrome vs. asymptomatic), degree of risk-factor control, SYNTAX scoring methods, and sample size. In diabetic patients, medial arterial calcification can falsely elevate ABI, potentially reducing its sensitivity — SD a limitation acknowledged in meta-analyses (20, 24, 25). Some studies included predominantly acute coronary syndrome patients, in whom more active and extensive atherosclerosis may produce stronger ABI-SYNTAX correlations than observed in our stable angina cohort (17).

Medial arterial calcification in diabetic patients may cause falsely normal or elevated ABI values, potentially leading to underestimation of peripheral disease in some individuals; complementary measures such as the Toe-Brachial Index could be considered in this subgroup. Although multivariable adjustment was performed, residual confounding by factors such as duration of diabetes, current medication intensity, inflammatory markers, or socioeconomic status cannot be fully excluded. The study population was recruited from two tertiary centers in Iran, which may limit generalizability to other ethnic or healthcare settings. Limitations related to medial calcification in diabetes and the need for larger, longitudinal, multicenter studies to confirm long-term prognostic implications should be acknowledged.

5.1. Conclusions

In patients with T2DM presenting with stable angina who underwent coronary angiography, abnormal ABI was present in approximately one-fourth of cases and was strongly and inversely associated with the severity and extent of coronary atherosclerosis as measured by SYNTAX score. Lower ABI, together with elevated LDL, hypertension, and higher HbA1c, emerged as an independent predictor of more severe coronary disease. Given its simplicity, low cost, and non-invasive nature, ABI measurement can serve as a valuable adjunctive tool (alongside traditional risk factors) for identifying diabetic patients at higher risk of complex coronary atherosclerosis. Routine ABI measurement in diabetic patients with stable angina may help prioritize early invasive evaluation or intensification of preventive therapies in those at highest risk of complex coronary disease.