1. Background

In many societies, suicide prevention efforts predominantly target younger populations due to their higher reported rates of suicidal ideation and attempts (1). Adolescents and young adults frequently appear in media reports, policy priorities, and academic research, often overshadowing the needs of other vulnerable groups. Globally, suicide is the second leading cause of death among individuals aged 15 to 29, with studies estimating that suicidal thoughts in this demographic range from 9% to nearly 30% (2). While such attention is warranted given the severity of youth suicide rates, it has inadvertently marginalized older adults in public health strategies.

Older populations face distinct psychosocial challenges — including chronic illnesses, bereavement, reduced autonomy, and social isolation — that increase their vulnerability to suicide but often remain underexamined. In fact, elderly individuals are significantly more likely to complete suicide compared to younger individuals, despite reporting fewer attempts (3). For example, in the United States in 2021, people aged 60 and above made up about 13% of the population but accounted for approximately 20% of all completed suicides (4). Projections suggest that by 2030, older adults may represent one-third of all suicides if current trends continue (5). This imbalance between actual suicide outcomes and policy attention highlights a critical gap in prevention efforts that urgently needs to be addressed.

The elevated lethality of suicide attempts among the elderly is well documented. Older adults are more likely to use violent and fatal methods such as firearms or hanging, and their intent to die is often stronger and more premeditated (6). According to Beck’s theory, while younger individuals may express suicidal ideation impulsively or as a cry for help, older individuals typically act with greater resolve, perceiving suicide as a rational escape from prolonged suffering. Their decisions are more frequently driven by chronic pain, loneliness, and a perceived burden on others (7).

In contrast, suicidal ideation in young people is often intertwined with acute emotional crises. These may include anger, guilt, revenge, or the desire to provoke a response from others. Many such behaviors serve communicative purposes, aiming to express distress rather than a definitive intent to die (8). Therefore, age-sensitive interpretation of suicidal behavior is crucial in both research and clinical practice (9).

Cultural factors also exert a strong influence on suicide-related behavior, especially in non-Western and collectivist societies. In Iran, for instance, family responsibilities, religious values, and social expectations may play a protective role, especially among the elderly. Despite this, few studies have examined how these cultural elements influence age-specific patterns of suicidal ideation and the protective reasons that deter individuals from attempting suicide. A deeper understanding of these culturally embedded factors is essential for designing effective, context-sensitive prevention strategies (10).

In regions like Kermanshah — a socio-culturally diverse area of western Iran — religion, familial ties, and social duty are deeply embedded in everyday life. Such cultural norms can serve as both protective and risk factors, depending on how individuals internalize them. For instance, while strong moral objections to suicide rooted in religious doctrine may prevent some from acting on suicidal thoughts, others may feel trapped by cultural expectations that discourage help-seeking or emotional disclosure (11).

Additionally, family structure plays a critical role. Parenthood and a sense of duty toward one's children often emerge as strong reasons for living (RFL) among older adults in Iranian culture. A finding from our study supports this: While only 13% of young participants reported being parents, over 90% of elderly participants had children, indicating a profound generational difference in perceived familial responsibility (12).

Despite these cultural nuances, most standardized tools used to assess suicidal ideation and protective beliefs were developed in Western contexts. While the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) and the RFL Inventory are well-validated instruments internationally, cultural adaptation is crucial for their use in Iran. In this study, the Persian versions of both tools were employed, which were translated and psychometrically validated in prior research — including adaptation for elderly populations. Nevertheless, further studies should continue to assess how effectively these instruments capture the lived experience of suicidal ideation in diverse cultural settings (13).

Another point of contention in the literature — and in this study’s preliminary abstract — is the misinterpretation of suicidal ideation levels across age groups. While the initial version of our abstract stated that no elderly participant showed severe suicidal ideation (BSSI ≥ 15), 59% reported mild ideation (BSSI scores between 1 - 14). In fact, our results show that 59% of older adults reported at least mild ideation on the BSSI. However, the severity levels were generally lower compared to the younger group, and the proportion of severe ideation was markedly smaller among the elderly. This emphasizes the importance of precise language and clear differentiation between presence, intensity, and clinical significance of suicidal thoughts (14).

Incorporating this understanding into public health messaging is crucial. Suicidal ideation in older adults often goes unnoticed due to their reluctance to seek help, societal stigma, and generational attitudes toward mental health. Elderly individuals may perceive discussing suicidal thoughts as shameful or burdensome, which limits their engagement with supportive resources such as crisis centers, counseling, or psychiatric care. Their suffering may remain internalized, further increasing their risk of suicide (15).

On the other hand, elderly individuals often express strong life-sustaining beliefs that can be leveraged in suicide prevention. Previous research has shown that older adults often score higher on subscales of the RFL Inventory, particularly in areas such as moral objections to suicide, concern for children, and family responsibility. These beliefs reflect long-standing cultural, spiritual, and relational investments that enhance resilience. In contrast, younger individuals may lack such deeply rooted protective frameworks, making them more susceptible to fluctuations in emotional states and social stressors (16).

2. Objectives

In light of these observations, this study aims to compare suicidal ideation and RFL between two distinct age groups — young adults (18 - 25) and older adults (60 and above) — in Kermanshah, Iran. By using culturally adapted instruments and stratified sampling methods, we seek to identify age-specific patterns in suicide risk and resilience. The findings are expected to inform targeted intervention strategies that address the unique psychological, familial, and cultural dynamics of each demographic (17).

Ultimately, a nuanced understanding of both risk and protective factors across the lifespan will support more effective and inclusive suicide prevention efforts. Especially in cultural contexts like Iran, where religion and family play central roles in shaping identity and behavior, prevention programs must integrate these cultural assets rather than adopt one-size-fits-all models developed in Western settings.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This research employed a causal-comparative design to explore differences in suicidal ideation and RFL across two distinct age groups. The study population consisted of elderly individuals (aged 60 and above) and young adults (aged 18 to 25) residing in Kermanshah province, Iran. Using stratified random sampling, participants were recruited from both urban and rural districts to reflect a range of socioeconomic statuses, gender identities, and educational backgrounds. Recruitment was conducted through local health centers, community organizations, and university networks to ensure demographic balance. Efforts were made to approximate the age-gender distribution outlined in the most recent Kermanshah census to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Response rates were approximately 82% overall, and demographic distributions (age, gender, education) were reviewed and found to closely align with the most recent census data from Kermanshah province.

A total of 124 individuals voluntarily participated in the study, divided evenly across the two age groups. All participants provided informed consent after receiving a clear explanation of the study’s goals, procedures, and ethical safeguards. Participation was anonymous, and individuals were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation

The BSSI is a 19-item self-report questionnaire used to assess suicidal thoughts, plans, and intent. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, yielding a total score range of 0 to 38. The instrument consists of three subscales: Desire for death, preparation for suicide, and actual suicide desire.

The Persian version of the BSSI used in this study was translated using forward-backward translation and validated in Iranian populations, including the elderly. Its Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients range from 0.81 to 0.95, with strong test-retest reliability (R = 0.88) reported in previous research (18-20).

3.2.2. Reasons for Living Inventory

The RFL Inventory, originally developed by Linehan et al., consists of 48 items assessing beliefs that serve as protective factors against suicide. Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 ("not at all important") to 6 ("extremely important"). The RFL comprises six subscales: Survival and coping beliefs, responsibility to family, concern for children, fear of suicide, fear of social disapproval, and moral objections (21).

A short-form version of the RFL for elderly populations was psychometrically validated in Iran by Rostami et al. Their study confirmed strong reliability (e.g., test-retest R = 0.84) and acceptable construct validity in both clinical and non-clinical elderly groups. The questionnaire showed meaningful negative correlations with suicidal ideation and depression, and good model fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Therefore, the instrument is considered culturally appropriate and psychometrically sound for assessing protective beliefs in Iranian elderly samples (22).

3.3. Procedure

Data were collected between April and August 2023. After obtaining informed consent, participants were asked to complete the BSSI and RFL questionnaires in person at designated community centers or via secure online platforms, depending on accessibility. Trained research assistants were available to assist elderly participants who had difficulties with reading or writing. To protect participant well-being, ethical protocols were in place to respond to signs of acute suicidal risk. Any participant who scored in the severe range on the BSSI (≥ 15) was referred to a licensed clinical psychologist affiliated with the Hamraz Counseling Center. Additionally, brief psychoeducation materials and a list of local mental health resources were offered to all participants after data collection.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25 (23). After initial screening for missing data, assumptions of normality were tested. Outliers were detected and removed using Mahalanobis Distance. For hypothesis testing, independent t-tests were used to compare means between the two groups on the BSSI and RFL total and subscale scores. Where normality assumptions were violated, Mann-Whitney U tests were employed as non-parametric alternatives. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated to assess the practical significance of the findings. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05. Bonferroni correction was applied to control for type I error in multiple comparisons.

4. Results

After reviewing and scoring the questionnaires, the following results were obtained. The participants included both men and women. In terms of age, the lowest frequency was related to those aged 23 to 25 years (7%), while the highest frequency was shared between the 25 to 30 years age group among young adults and the 60 to 65 years age group among older adults (41.6%).

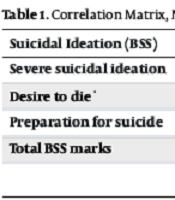

In Table 1, the descriptive statistics for the variables are presented separately for the elderly and young age groups. As shown in Table 1, both groups displayed evidence of suicidal ideation. For the younger group, the scores on the BSSI ranged from 0 to 23, with 65% showing mild suicidal ideation, defined by a non-zero score. For the older group, the scores ranged from 0 to 14, with 59% showing mild suicidal ideation. Additionally, 12% of younger individuals and 6% of older individuals reported moderate to severe suicidal ideation (severe suicidal ideation was defined as BSSI scores of 15 or greater, based on established cutoff points), although these differences were not statistically significant (n = 123, P = 0.17).

| Suicidal Ideation (BSS) | Elderly (Mean ± SD) | Youth (Mean ± SD) | t | d.f | P-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe suicidal ideation | 0.12 ± 0.49 | 0.31 ± 0.96 | 1.44 | 123 | 0.161 | 0.24 |

| Desire to die | 0.47 ± 1.05 | 0.86 ± 1.51 | 1.80 | 123 | 0.061 | 0.28 |

| Preparation for suicide | 0.99 ± 1.58 | 1.34 ± 2.10 | 1.20 | 123 | 0.231 | 0.18 |

| Total BSS marks | 2.43 ± 3.30 | 3.63 ± 9.94 | 1.86 | 123 | 0.066 | 0.28 |

Abbreviation: BSS, Beck Scale for suicide ideation.

To examine the differences in total suicidal ideation scores and its subscales (real suicide intent, death desire, and suicide preparation) between the groups, independent t-tests were used. Moreover, to determine which group differences were significant, the Bonferroni post-hoc test was employed. As seen in Table 1, there was no significant difference between the age groups in terms of suicidal ideation and its subscales. Given the non-normal distribution of the sample, non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney U) were also utilized, yielding the same results. Therefore, it can be concluded that the types and levels of suicidal thoughts do not significantly differ between the two age groups studied. The effect size (Cohen's d) was small (ranging from 0.18 to 0.28), indicating that age had a minimal impact on the types and levels of suicidal thoughts.

Next, to explore differences in the total RFL scores and its subscales (survival and coping beliefs, responsibility to family, child-related concerns, fear of social disapproval, and moral objections) between the groups, independent t-tests and Bonferroni post-hoc tests were employed. As shown in Table 2, older adults scored higher on the subscales of moral objections, responsibility to family, and child-related concerns compared to the younger group.

| RFL | Elderly (Mean ± SD) | Youth (Mean ± SD) | t | d.f | P-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival and coping beliefs | 4.95 ± 0.96 | 4.73 ± 0.76 | 1.53 | 123 | 0.133 | 0.27 |

| Concerns about children | 4.94 ± 1.73 | 4.92 ± 1.91 | 3.69 | 123 | 0.004 a | 0.46 |

| Responsibility to family | 4.48 ± 1.41 | 3.34 ± 1.01 | 2.31 | 123 | 0.003 a | 0.34 |

| Moral objections | 4.62 ± 1.43 | 3.35 ± 1.46 | 2.69 | 123 | 0.005 a | 0.42 |

| Fear of social disapproval | 4.11 ± 1.28 | 3.08 ± 1.36 | 0.37 | 123 | 0.654 | 0.35 |

| Fear of suicide | 2.34 ± 1.12 | 3.19 ± 1.02 | 1.91 | 123 | 0.432 | 0.23 |

| Total BSS marks | 4.24 ± 1.32 | 3.86 ± 1.23 | 1.42 | 123 | 0.381 | 0.36 |

Abbreviation: RFL, reasons for living.

a P < 0.01.

5. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to compare the prevalence and characteristics of suicidal ideation and RFL between younger (18 - 25 years) and older (60 years and above) adults in Kermanshah, Iran. Contrary to some prior assumptions and portions of our preliminary text, the findings demonstrated that suicidal ideation exists in both age groups, albeit with differences in intensity and protective psychological factors. Importantly, 59% of elderly participants reported mild suicidal ideation, while 65% of young adults exhibited similar patterns. Although the proportion of participants with severe ideation (BSSI ≥ 15) was higher among the young group (12% vs. 6%), the difference was not statistically significant. These findings correct the previously stated claim that elderly individuals “exhibited no signs of suicidal ideation”, which was inaccurate and rightly flagged by reviewers. The presence of even mild ideation in a majority of elderly participants calls for greater attention to this often-overlooked population in suicide prevention efforts.

What clearly differentiated the two groups, however, was the strength of protective beliefs. Older adults scored significantly higher on three critical RFL subscales: Moral objections to suicide, responsibility to family, and concerns about children. These findings are in line with existing research suggesting that culturally and socially ingrained values serve as a powerful deterrent to suicide in older adults (24-26). In particular, moral and religious beliefs, as well as intergenerational obligations, are deeply embedded in Iranian culture. These beliefs can act as internalized barriers against suicidal behavior, even in the face of significant psychological distress (27, 28).

The clinical significance of these findings should not be underestimated, despite small to moderate effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.34 - 0.46). Because, in the context of suicide prevention, even small shifts in protective cognition can yield meaningful differences in behavior and outcomes — particularly when such beliefs are closely aligned with cultural values. Suicide prevention is not only a matter of symptom reduction but also of strengthening internal and social resources that support resilience and meaning-making (29).

These results also emphasize the importance of contextualizing suicidal ideation. While suicidal thoughts in youth may often emerge from emotional reactivity, impulsivity, or social conflict (such as guilt, rejection, or academic failure), suicidal ideation in the elderly often reflects chronic suffering, existential despair, or a perceived loss of dignity and autonomy (30, 31). The elderly are also more likely to act on suicidal thoughts with lethal intent, often choosing more violent methods and rarely communicating their distress. This makes detection and prevention particularly challenging (32, 33).

Moreover, this study found a significant disparity in parental status between groups: Ninety percent of older adults were parents, whereas only 13% of young adults reported having children. This difference is not merely demographic — it has profound psychological implications. Parenthood, in many cultures including Iran, is strongly linked to self-worth, life purpose, and interdependence. Older adults may feel that they have an enduring role and obligation to their children and grandchildren, which can counter suicidal impulses. This aligns with studies indicating that family responsibility is a strong reason for living among adults in later life (34, 35).

The higher scores of the elderly on the moral objections subscale also reflect the sustained influence of religious and ethical frameworks in this population. Islam, which is predominant in Iran, generally prohibits suicide, emphasizing the sanctity of life and accountability in the afterlife. For older adults who have been socialized in such moral systems, these beliefs likely serve as strong cognitive barriers to suicide, even when other protective factors (e.g., physical health, social activity) decline (36).

In contrast, younger adults — despite having higher emotional expressiveness and access to support — may lack these structured internal belief systems. Their protective beliefs may be more fragile, especially in times of acute emotional distress. Therefore, suicide prevention strategies for youth must go beyond symptom control and focus on developing meaning, identity, community connection, and purpose, especially in transitional periods such as entering university or facing unemployment.

The findings also suggest that preventive interventions for the elderly should not rely solely on medical or psychological models. Rather, they should integrate spiritual counseling, family engagement, and community-based elder support programs. Promoting social connectedness, respecting autonomy, and reinforcing the individual's role in family and community life may significantly enhance life satisfaction and reduce suicide risk (37).

5.1. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that suicidal ideation exists across the lifespan in both youth and older adults. However, protective factors — particularly those rooted in moral values, religious beliefs, and familial responsibility — are significantly stronger among the elderly. These findings emphasize the need for culturally sensitive, age-specific suicide prevention strategies. For older adults, interventions should focus on reinforcing existing life-preserving beliefs and facilitating their ongoing role in family and society. For youth, the challenge lies in cultivating new sources of purpose, connection, and identity, particularly in the face of uncertainty and social pressure.

Ultimately, suicide prevention in Iran and similar contexts must move beyond Western-centered, symptom-focused models. It should embrace a holistic approach that integrates cultural, spiritual, and familial dimensions to effectively address the unique needs of different age groups.

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sample size (n = 124), while sufficient for detecting group-level differences, may not fully capture the diversity within each age group. Additionally, the sample was non-clinical, limiting generalizability to high-risk psychiatric populations. Future studies should replicate these findings in clinical samples, including patients with diagnosed mood disorders, chronic pain, or terminal illnesses.

Second, while validated Persian versions of the BSSI and RFL were used, the study did not include qualitative interviews that might have captured deeper, culturally nuanced understandings of suicide and resilience. Incorporating mixed-method approaches in future research could offer richer data on how older and younger adults perceive their life circumstances, obligations, and beliefs.

Third, the cross-sectional design prevents any inference of causality between protective factors and suicidal ideation. Longitudinal research is needed to explore how protective beliefs evolve over time and how life transitions — such as retirement, bereavement, or economic hardship — influence ideation and behavior.

Finally, although an ethical protocol was in place to refer participants scoring high on BSSI to mental health professionals, a more detailed suicide risk protocol (e.g., structured interview follow-up, immediate intervention availability) would enhance the safety and validity of future research in this sensitive area.