1. Background

Hookah smoking (HS) among teenagers, especially girls, has been increasing in recent years in Iran. This phenomenon not only threatens the physical and mental health of adolescents but also brings significant social and economic costs (1). The importance of this issue becomes even more evident as research indicates that the adverse effects of HS could be more pronounced in women compared to men in some aspects (2).

Various concepts and determinants influence the tendency toward HS, among which a positive attitude toward it is one of the key factors and may serve as a stronger predictor (3, 4). In some studies, subjective norms, behavioral intention, and a person's perceptions of hookah and people who smoke hookah have been mentioned as predictive factors in HS (5, 6). Several theories and models have been used to understand the reasons behind hookah use among teenagers, but none have been able to fully explain all aspects of it due to its multifactorial causal nature. In this regard, a collection of models and patterns in health education and health promotion have addressed the issue of hookah use (7).

When individuals consider engaging in risky behavior, such as smoking hookah, they weigh all aspects of the behavior before deciding whether to proceed or not. In this decision-making process, false beliefs about hookah, such as it being less harmful and the idea that water filters out toxins, can lead individuals to underestimate the risks, thereby encouraging them to engage in the behavior (8). In the second case, the person performs the risky behavior without any rational intention and decision, based only on imaginations, desires, and special circumstances that have arisen. The prototype willingness model (PWM) addresses this issue (6).

The PWM model consists of several constructs, including attitude, subjective norms, prototype perceptions, willingness, intention, and behavior (6). This model, proposed by Gibbon et al. (9), states that the intention to perform a behavior is predicted by two factors: (A) attitude, which is a person's positive or negative evaluation of performing a behavior, and (B) subjective norms, which are the social pressures perceived by the person to perform or not perform the target behavior. Furthermore, in this model, the framework of prototype perceptions — or the mental images individuals have of those who engage in risky behaviors — shapes behavior by influencing their willingness to act. The effectiveness of this model has been confirmed in some studies (10).

Despite the importance of HS, comprehensive and in-depth studies are inadequate in Iran to examine the reasons and motivations behind this behavior in adolescent girls. Iranian culture and social norms shape the factors influencing adolescent behavior in a way that differs from other societies. Given the need to identify the determinants of HS behavior, this study was designed and conducted.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the predictors of HS among girl students based on the PWM.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted in February 2022 among 407 girl high school students in grades 10 to 12 in Kermanshah. The target population comprised all high school students during the academic year 2021 - 2022. The sample size was determined based on the prevalence of hookah consumption among students in a similar study (9), considering an 18% prevalence, a 95% confidence level, and a margin of error of 7%. The minimum required sample size, calculated using PASS software, was 300 individuals. To ensure reliability, a total of 407 individuals were ultimately selected using a simple random sampling method.

The sampling method was multi-stage with a simple random approach. For sampling, a list of 25 girls' high schools in district 3 of the Kermanshah Education Department was prepared. The reason for selecting this district was its diversity and extent compared to other regions. In the second stage, six schools out of the 25 schools, which had all three educational levels, were randomly selected after determining the number of samples required for each school, proportional to the number of students in grades 10 to 12. The inclusion criteria for this study were the willingness to participate, being in grades 10 to 12, and residing in Kermanshah, while the exclusion criterion was the failure to complete the questionnaire.

3.2. Data Collection Tool

The questionnaire was developed based on the PWM, and its validity and reliability had been empirically validated in prior studies (6). Consisting of 44 items, the instrument was selected for its robust psychometric properties and alignment with the study’s focus on evaluating participants' behavioral intentions and situational willingness. The sections of this questionnaire are explained below.

3.2.1. Behavior

To measure 'behavior', a single binary item (Yes/No) was used. The frequency of behavior was assessed using the following response options: "Every day", "3 - 5 times per week", "1 - 2 times per week", "once a month", "rarely", and "never".

3.2.2. Intention

Three questions were used to measure 'intention'. Participants were asked to respond to the following statements: (1) "I have decided not to smoke hookah this year," (2) "I will always try not to smoke hookah," and (3) "I do not want to start smoking hookah at all."

3.2.3. Willingness

Eight questions were used to measure 'willingness'. Participants were asked to respond to scenarios where they were offered hookah and had to choose from four response options: (1) "I would take the hookah and smoke it," (2) "I would say no, thank you, and decline the offer," (3) "I would leave the group," or (4) "I would smoke only once to avoid upsetting them."

3.2.4. Prototype Perceptions

measure 'prototype perceptions', 12 items were used. Participants were asked, "Imagine that one of your classmates or friends your age smokes hookah regularly. In your opinion, which of the following adjectives best describes him/her?"

3.2.5. Subjective Norms

To measure 'subjective norms', 5 items were used. These items measured the perceived expectations of friends and family about HS.

3.2.6. Attitude

To measure 'attitudes', 9 items were used. These items assessed participants’ attitudes toward HS, such as perceived risks compared to cigarettes. A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from strongly agree (5) to strongly disagree (1).

3.3. Ethical Considerations

Given the sensitive nature of the questionnaire’s focus on hookah use, the instrument was disseminated through the school’s official social media channels to ensure controlled and ethical participant access. This platform was selected to maintain anonymity, encourage candid responses, and align with the digital engagement patterns of the target demographic. The purpose of the study was also explained, and all participants provided informed consent. The Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences approved this study (IR.KUMS.REC.1399.503).

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation) were calculated for all variables. Inferential statistics, including Pearson correlation coefficient and linear and logistic regressions, were used to examine the relationships between variables. Linear regression was used to examine the associations between model constructs. Logistic regression was employed to assess binary outcomes (hookah use) in relation to other factors.

The survey link was distributed through the school’s official communication channel. Upon the conclusion of the data collection period, the link was promptly removed from the group. Data collection lasted for one month. Given the sensitive nature of the topic, detailed instructions were provided to participants to ensure clarity and understanding. Additionally, the confidentiality of all collected data was rigorously emphasized, and participants were assured that their responses would remain secure and anonymous throughout the study.

4. Results

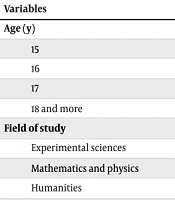

Most of the students were 17 years old and were enrolled in humanities or experimental sciences. Most of the parents had a high school diploma, and the father's occupation was self-employed. According to the findings, 10.56% of the students had smoked hookah in their lifetime, and 5.6% had smoked hookah in the past year. Part of the descriptive results of this research has been presented elsewhere (11). The data related to the structure of the model will be explained in the following tables.

Table 1 indicates that participants who had tried hookah before showed a significantly greater intention to continue smoking hookah compared to those who had never tried it (P < 0.01). However, the willingness to quit hookah did not differ significantly between participants with and without prior experience of using it (P = 0.123).

| Spearman Coefficient | Intention | Willingness | Prototype Perceptions | Subjective Norms | Attitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | |||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.001 | 0.023 | -0.018 | 0.464 a | 0.426a |

| P | - | 0.642 | 0.725 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Willingness | |||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.023 | 0.001 | 0.137 a | 0.165 a | -0.016 |

| P | 0.642 | - | 0.006 | 0.001 | 0.740 |

| Prototype perceptions | |||||

| Correlation coefficient | -0.018 | 0.137 a | 0.001 | 0.062 | 0.138 a |

| P | 0.725 | 0.006 | - | 0.209 | 0.005 |

| Subjective norms | |||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.464 a | 0.165 a | 0.062 | 0.001 | 0.464 a |

| P | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.209 | - | 0.001 |

| Attitude | |||||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.426 a | -0.016 | 0.138 a | 0.464 a | 0.001 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.740 | 0.005 | 0.001 | - |

a Mann-Whitney Test.

Table 2 indicates that both intention and willingness were related to hookah use behavior, after controlling for prototype perceptions. Specifically, as intention increased, the likelihood of using hookah also increased. Willingness also had a positive correlation with hookah use, but its impact was weaker compared to intention.

| Variables | Meaningfulness (P) | OR |

|---|---|---|

| Intention | < 0.001 | 1.99 |

| Willingness | 0.028 | 0.836 |

| Constant | 0.599 | 0.321 |

Table 3 demonstrates that both attitude and subjective norms were significantly associated with intention. Between these two variables, subjective norms had a stronger association, as indicated by its larger standardized beta value (B = 0.369). However, because the R2 value was low (R2 = 0.394), these variables (attitude and subjective norms) were not strong predictors of intention overall.

| Variables | Standardized Beta | Meaningfulness (P) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent factors | 0.394 | ||

| Attitude | -0.360 | < 0.001 | |

| Subjective norms | 0.369 | < 0.001 | |

| Prototype perceptions | 0.063 | 0.113 |

Table 4 indicates that attitude, subjective norms, and prototype perceptions were all significantly related to willingness. Among these three factors, subjective norms had the strongest association, as shown by its higher standardized beta value compared to the other two variables (B = 0.172). However, since the R2 value was low, these three variables (attitude, subjective norms, and prototype perceptions) were not strong predictors of willingness overall.

| Variables | Standardized Beta | Meaningfulness (P) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent factors | 0.065 | ||

| Attitude | 0.164 | 0.004 | |

| Subjective norms | 0.172 | 0.002 | |

| Prototype perceptions | 0.164 | 0.001 |

Table 5 shows that the variance of those who are offered hookah by friends is 6.07 times greater than those who do not receive this offer (P = 0.002).

| Variables | Consumed During Life; N = 43 (%) | Adjusted Odds Ratio | P-Value | Current Consumer; N = 23 (%) | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||||

| 15 | 3 (7) | Reference (1) | 0.570 | 1 (4.3) | Reference (1) |

| 16 | 11 (25.6) | 0.362 | 0.248 | 3 (0.13) | 0.167 |

| 17 | 16 (37.2) | 0.347 | 0.212 | 11 (47.8) | 1.091 |

| 18 and more | 13 (30.3) | 0.526 | 0.471 | 8 (34.8) | 1.237 |

| Field of study | |||||

| Experimental sciences | 18 (41.9) | Reference (1) | 0.151 | 12 (52.2) | Reference (1) |

| Mathematics and physics | 5 (11.6) | 2.077 | 0.286 | 2 (8.7) | 0.360 |

| Humanities | 20 (46.5) | 2.713 | 0.056 | 9 (39.1) | 0.694 |

| Father's occupation | |||||

| Government employee | 14 (6.32) | Reference (1) | 0.318 | 9 (39.1) | Reference (1) |

| Self-employed | 24 (8.55) | 0.655 | 0.467 | 11 (47.8) | 0.249 |

| Retired | 1 (3.2) | 0.660 | 0.742 | 1 (4.3) | 1.363 |

| Unemployed | 4 (3.9) | 2.948 | 0.269 | 2 (8.7) | 0.515 |

| Mother's occupation | |||||

| Government employee | 7 (16.3) | Reference (1) | 0.373 | 5 (21.7) | Reference (1) |

| Self-employed | 2 (4.7) | 0.148 | 0.136 | 1 (4.3) | 0.135 |

| Retired | 1 (2.3) | 0.554 | 0.708 | 1 (4.3) | 0.195 |

| House wife | 33 (76.7) | 0.321 | 0.131 | 16 (69.6) | 0.039 |

| Number of children in the family | |||||

| 1 | 8 (18.6) | Reference (1) | 0.389 | 3 (13) | Reference (1) |

| 2 | 20 (46.5) | 0.563 | 0.322 | 15 (65.2) | 1.192 |

| 3 | 8 (18.6) | 0.287 | 0.090 | 1 (4.3) | 0.108 |

| 4 | 3 (7) | 0.093 | 0.048 | 1 (4.3) | 0.011 |

| 5 | 3 (7) | 0.580 | 0.639 | 2 (8.7) | 8.778 |

| 6 | 1 (2.3) | 0.648 | 0.806 | 1 (4.3) | 17.152 |

| Family consumption | 24 (55.8) | 4.113 | 0.006 a | 13 (56.5) | 1.627 |

| Friends consumption | 26 (60.5) | 2.068 | 0.187 | 17 (73.9) | 18.897 |

| Friends' suggestion | 26 (60.5) | 6.071 | 0.002 a | 12 (52.2) | 0.579 |

| Friends' insistence | 12 (27.9) | 3.205 | 0.064 | 5 (21.7) | 1.311 |

a Mann Whitney Test.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the critical roles of subjective norms, attitude, and prototype perceptions in shaping hookah consumption behaviors among adolescent girls, mediated through their correlations with intention and behavioral willingness. These results align with the PWM but also reflect unique cultural dynamics specific to Kermanshah’s sociocultural landscape. In Iran, where familial and societal expectations may heavily affect adolescent behavior (12-17), subjective norms such as peer approval or familial acceptance of hookah use may carry disproportionate weight. For instance, HS is often socially normalized in certain gatherings, particularly in urban settings, despite its health risks (18). This cultural ambivalence creates a conflict between perceived social rewards and health-related prototype perceptions, a tension amplified by gendered norms that scrutinize adolescent girls’ behaviors more intensely than boys’ (18).

Furthermore, the influence of familial and societal expectations on adolescent hookah use must be contextualized within geographical disparities observed across Iran. A recent study highlights significant regional variations, with certain provinces reporting markedly higher rates of hookah consumption. This geographical divergence suggests that localized cultural norms and socioeconomic conditions may exacerbate or attenuate the social dynamics previously discussed (19).

Attitudes toward hookah use are often shaped by misconceptions about its harmfulness compared to cigarettes, a phenomenon documented in studies highlighting the role of media and social networks in perpetuating these beliefs (20). The interplay between low prototype perceptions and positive social reinforcement may explain why intentions to abstain fail to translate into behavioral resistance, particularly in contexts where hookah is framed as a marker of social cohesion or maturity.

This study’s emphasis on cultural context is pivotal. For example, the collectivist nature of Iranian society, where group conformity often overrides individual health decisions, may amplify the association of subjective norms. Interventions targeting hookah use among Iranian adolescent girls must therefore address these culturally embedded drivers, e.g., through community-based campaigns involving family members and leveraging religious leaders to reframe social narratives (21).

The family interaction theory proposed by Brook also emphasizes the importance of the parent-child bond as a protective factor. It highlights three key aspects of parenting that contribute to healthy child development: Positive emotional bonding, consistent rules, and flexibility. A supportive and nurturing home environment is essential for adolescent well-being (17). Individuals' experiences and positive interactions with people who refrain from using hookah can positively influence their perceptions of hookah abstinence. These experiences can lead to a more positive evaluation of abstaining from hookah use and a greater willingness to engage in this behavior in the future (18).

The behavioral analysis presented in Table 2 demonstrates that both intention and willingness are associated with hookah use behavior. The results indicate that intention is the strongest predictor of hookah use behavior (OR = 1.99, P < 0.001). This finding is consistent with psychological models such as the theory of planned behavior (TPB), which emphasizes intention as a key determinant of behavioral engagement (22). A one-unit increase in intention nearly doubles the likelihood of hookah use, underscoring the critical role of cognitive planning in health-related behaviors. This suggests that interventions aimed at reducing hookah consumption should focus on modifying attitudes and reinforcing intentions to abstain.

Contrary to expectations, willingness exhibited a weaker association with hookah use (OR = 0.836, P = 0.028). This result implies that willingness alone may not be a robust predictor of behavior and could be mediated by external factors such as social norms or accessibility. The analysis controlled for prototype perceptions, revealing that intention and willingness remain significant predictors even after accounting for these factors.

The results of this study highlight the necessity of developing targeted communication strategies that underscore the dangers of hookah use, particularly to elevate risk perception among high school-aged girls. Empirical evidence indicates that interventions focusing on modifying beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward hookah consumption can significantly shape usage patterns (23).

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, it can be concluded that subjective norms and prototype perceptions significantly affect the tendency to use hookah in adolescent girls. In particular, subjective norms play a very important role in this regard. The results of the present study showed that PWM structures can provide a suitable theoretical framework for identifying factors related to hookah use in adolescents.

5.2. Limitations

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting and generalizing the findings. The study has a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to establish causal relationships or track changes over time. The study only shows a correlation between the variables, and it cannot be definitively stated that behavioral intentions, social norms, or attitudes cause hookah use. Other factors may also play a role in this relationship. Data was collected using a questionnaire, and the analysis relied on the information provided by the students. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases such as social desirability or memory errors. The honesty of the participants in completing the questionnaire, given the sensitive nature of the topic, is uncertain. To minimize the impact of this issue, participants were clearly and thoroughly informed that their information would remain completely confidential and would not be misused.

Future studies should consider longitudinal designs to better understand trends and causal factors. Using mixed-methods approaches, such as combining surveys with interviews, could provide deeper insights. Developing targeted interventions for female adolescents and comparing cultural and policy impacts would further enhance understanding and prevention efforts.