1. Background

Addiction is a chronic and relapsing disorder characterized by the compulsive use of addictive substances despite the presence of adverse effects. It causes physiological and behavioral changes, and the cessation of substance use leads to withdrawal symptoms (1). Addiction has numerous personal and social effects; it can not only impact personal relationships but also involve other family members (2). Several studies have shown that addiction reduces quality of life, life expectancy, and self-esteem (3). The economic burden of addiction can impose significant costs on a country. In Canada in 2014, the total cost of productivity lost due to substance use was $15.7 billion, or approximately $440 per Canadian resident (4).

About 5.6% of the world’s population aged 15 - 64 have consumed an addictive substance at least once (5). In 2011, the prevalence of addiction in the U.S. was estimated to be between 15 - 61% (6). More than 70% of addicts are employed, meaning they hold jobs (7). Several factors have been identified that increase susceptibility to addiction, including major depressive disorder, low income, negligence, and ease of access to substances (5). The role of work in the occurrence of addiction has been discussed for a long time. Unemployment can be a contributing factor to addiction. Various occupational factors have also been discussed regarding their impact on increasing the occurrence of addiction (8). People typically spend long hours at work; therefore, risk factors in the work environment can play an accelerating role in addiction.

In addition to the effects of addiction, occupational predisposing factors can reduce work quality and productivity, as well as pose a risk of predisposing colleagues to addiction. Studies have shown that having an addicted colleague is a risk factor for addiction (9, 10). Access to drugs in the workplace, being away from family, job burnout, work stress, and long working hours are factors that may contribute to addiction (11-13). One study revealed that restaurant employees who continued working during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to those who had been furloughed, experienced higher levels of psychological distress, drug abuse, and alcohol use (14). Employees may not be able to change many of these factors. Various approaches have been proposed to reduce these factors, and while their effectiveness is open to debate, workplace interventions and prevention strategies are associated with reduced substance abuse (15, 16).

2. Objectives

Considering the increasing prevalence of addiction and the lack of official reports on the population of addicts in Iran, the present study aimed to investigate the prevalence of work-related factors among individuals suffering from addiction.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Population

The present cross-sectional study used a census for data collection. All male patients who visited the addiction treatment center of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences during 2020 and met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were having experienced at least one job, consenting to participate in the study, being diagnosed with addiction by a psychiatrist or a doctor specializing in addiction treatment, and receiving care services for addiction.

3.2. Study Protocol

All patients who met the inclusion criteria during the project timeframe were included in the study. Patients visited the addiction treatment center monthly, where all completed the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) Questionnaire and the job conditions checklist. After obtaining informed consent, participants’ information was collected and divided into five categories.

3.2.1. Demographic Information and Educational Degrees

Due to the wide range of educational degrees in Iran, participants were divided into three categories: Illiterate participants, those with less than a bachelor’s degree (considered low-level), and those with a higher degree (considered high-level).

3.2.2. Past Medical History

This included a history of psychiatric disease based on the documentation of patients’ medical records as well as information provided by patients and their drug history.

3.2.3. Work-Related Information

This was based on the job conditions checklist. According to the official classification of jobs and worker distribution in Iran, jobs were divided into six categories: Transportation, employees, service workers, technical workers, construction workers, and agriculture/livestock.

3.2.4. Job-Related Predisposing Factors

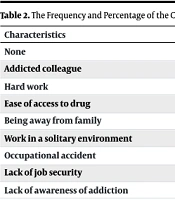

These included the presence of an addicted colleague, hard work, access to drugs in the workplace, being away from family, working in a solitary environment, occupational accidents, lack of job security, and low awareness of addiction.

3.3. Information Extracted from the Maudsley Addiction Profile Questionnaire

3.3.1. The Job Conditions Checklist

The job conditions checklist employed in our study is a simple, researcher-created instrument designed to assess various work-related factors that may influence substance use among participants. This checklist consists of several parts to inquire about the respondent’s job at the onset of addiction, current job, age at the onset of drug abuse, age at the onset of addiction, work experience, conditions of the work environment, income status, age at the onset of employment, shift work, job stress, job satisfaction, and ability to perform duties (the stages of development of drug addiction include the first use/experimental consumption, experimental consumption/irregular consumption, regular consumption, harmful consumption, dependency, and addiction.)

3.3.2. The Maudsley Addiction Profile Questionnaire

The MAP Questionnaire is designed to assess the outcomes of addiction treatment. This questionnaire inquired about addiction factors, physical and mental health, and the individual and social performance of the addict (17).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The sample size for this study was determined to be 185, with a power of 80% and an alpha of 5%. Considering missing or invalid data, a total of 210 cases were calculated to achieve the main objective of the thesis. The collected data were processed and analyzed using SPSS version 16. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies (percentages) and means (standard deviations), were calculated and presented in appropriate tables. After assessing the normality of the data, the relationships between qualitative and quantitative variables were examined using independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Additionally, Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were utilized to assess the correlation between quantitative variables. The association between qualitative variables was evaluated using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted for all statistical tests.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences approved this research project with code IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1398.845.

4. Results

The study included 210 participants with a mean age of 39 years (range: 34 - 47). The mean age at which participants first abused drugs was 22 years, and the mean age at the onset of addiction was also 22 years. The mean duration of drug abuse was 13 years (range: 7 - 20). The mean age at the onset of employment was 17 years (range: 15 - 20), and the mean length of work experience was 13.5 years (range: 5 - 20). Most participants did not receive any insurance services. Table 1 shows additional demographic information about the participants.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Level of education | |

| Illiterate | 18 (8.6) |

| Low level | 169 (80.5) |

| High level | 23 (11) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 18 (8.6) |

| Married | 188 (89.5) |

| Divorced | 4 (1.9) |

| Current job | |

| None (unemployed) | 17 (8.1) |

| Transportation | 22 (10.5) |

| Industrial workers | 28 (13.3) |

| Service workers | 55 (26.2) |

| Technical workers | 52 (24.8) |

| Construction workers | 29 (13.8) |

| Agriculture and livestock | 7 (3.3) |

| Job at the onset of addiction | |

| None (unemployed) | 6 (2.9) |

| Transportation | 13 (6.2) |

| Employees | 27 (12.9) |

| Service workers | 47 (22.4) |

| Technical workers | 63 (30.0) |

| Construction workers | 32 (15.2) |

| Agriculture and livestock | 11 (5.2) |

| Student or soldier | 11 (5.2) |

| Insurance status | |

| Covered | 74 (35.2) |

| Uncovered | 136 (64.8) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

In total, only one-third of addicts used a single type of drug, whereas the remaining two-thirds used two or more drugs simultaneously. A total of 169 participants (80.5%) reported using opium as their main substance.

The results of the study showed that 125 participants (59.8%) experienced job stress, and 89 participants (42.6%) were dissatisfied with their jobs. Among the job-related predisposing factors, the presence of an addicted colleague was the most important and frequent cause of drug abuse. Hard work and ease of access to drugs in the workplace ranked next, respectively (Table 2). There was no significant relationship between job-related predisposing factors across different occupations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| None | 52 (24.8) |

| Addicted colleague | 70 (33.3) |

| Hard work | 39 (18.6) |

| Ease of access to drug | 29 (13.8) |

| Being away from family | 8 (3.8) |

| Work in a solitary environment | 6 (2.9) |

| Occupational accident | 3 (1.4) |

| Lack of job security | 2 (1.0) |

| Lack of awareness of addiction | 1 (0.5) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

There was a statistically significant relationship between the type of current job and the number of drugs consumed. Specifically, 29.2% of service workers, 29.2% of technical workers, and 16.7% of unemployed individuals used more than five types of substances, ranking first in frequency (P = 0.045). There was no significant relationship between psychiatric disorders and the type of drug used concerning occupation (P > 0.05). Considering the effect of job type on the number of drugs abused, we attempted to test the relationship between job type and drug type. In these surveys, no significant relationship was found between these two factors (P = 0.065). Further investigations showed that, apart from the type of current job, the type of insurance and the presence of psychiatric disorders were significantly related to the number of drugs abused. Individuals with rural insurance and those without insurance had a higher number of consumed drugs (P = 0.033).

Seventeen participants (8.1%) in this study were affected by anxiety disorders, five participants (2.4%) by sleep disorders, and four participants (1.9%) by depression. Addicts with depression and anxiety had significantly higher rates of drug abuse than those without psychiatric disorders (P = 0.027, Table 3).

| Characteristics | Types of Job | P-Value (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (Unemployment, %) | Transportation (%) | Employee (%) | Service Worker (%) | Technical Worker (%) | Construction Worker (%) | Agriculture And Livestock (%) | ||

| Job stress | 0.122 | |||||||

| + | 82.4 | 63.6 | 53.6 | 65.5 | 50 | 50 | 85.7 | |

| - | 17.6 | 9.5 | 46.4 | 34.5 | 50 | 50 | 14.3 | |

| Job satisfaction | 0.001 | |||||||

| + | 17.6 | 36.4 | 71.4 | 69.1 | 65.4 | 50 | 42.9 | |

| - | 82.4 | 63.6 | 28.6 | 30.9 | 34.6 | 50 | 57.1 | |

There was a statistically significant difference among the jobs reviewed in this article in terms of income level, number of working days per week, and job experience (P < 0.001). A weak negative correlation was found between age, age at the onset of addiction, age at the onset of drug abuse, and the monthly amount of drug abuse with the number of drugs consumed.

5. Discussion

Investigating the influence of work-related factors on drug users is essential, as specific job conditions — such as elevated stress levels, extended working hours, and physically demanding tasks — can increase the likelihood of substance use and abuse. By understanding these factors, it is possible to foster safer work environments, enhance employee health and well-being, and mitigate productivity losses and healthcare expenses (18). Therefore, in this study, work-related factors among drug abusers were evaluated. The results indicated that significant contributors to drug abuse included the presence of an addicted colleague, hard work, and easy access to drugs in the workplace. Technical workers were the most involved occupational group at the onset of addiction, whereas service workers were the most affected in their current jobs. The frequency of drug use was significantly higher among service and technical workers, as well as unemployed individuals. Additionally, addicts with depression and anxiety exhibited a significantly higher frequency of drug use compared to those without psychiatric disorders. There were significant differences among the jobs reviewed in terms of income level, number of working days per week, and job history. A weak negative correlation was found between age, age at the onset of addiction, age at the onset of drug abuse, and the monthly amount of drug abuse with the number of drugs consumed.

No significant relationship was found between the type of drug abuse and occupation or psychiatric disorders. Work-related factors are increasingly contributing to the rise in drug abuse cases, which can negatively impact employees’ social health and impose significant costs on both firms and the government (19). Addiction can be influenced by both the absence and presence of employment. Joblessness often leads to financial difficulties, social disconnection, and a sense of aimlessness, all of which may drive individuals to use substances as a means of coping. The instability and pressure resulting from a lack of steady income can increase susceptibility to addiction (20). Conversely, certain aspects of employment can also contribute to substance abuse. Workplaces characterized by high stress levels, extended work hours, physically demanding duties, and exposure to addictive substances can foster the development of substance use disorders. To prevent addiction and create healthier work environments, it is essential to recognize and address these occupation-related factors (21).

Various studies have evaluated the occupational factors that influence the tendency of individuals to use drugs. In a study by Ghorbani et al., having a friend or friends who are addicted increases the likelihood of a person’s tendency to abuse drugs by 7.32 times (22). Similarly, Trucco found that having an addicted colleague was associated with an increased risk of an individual’s tendency toward addiction. However, in this study, being away from family and hard work were not recognized as risk factors (23). Research conducted in the United States and Russia has shown that, among interpersonal social factors, substance abuse by friends and relatives is positively associated with an individual’s susceptibility to addiction (24). The results of the present study indicate that substance abuse is significantly influenced by factors such as having an addicted colleague and experiencing difficult work conditions. Individuals with untreated anxiety and depression often resort to substance use as a means of self-medication to alleviate their symptoms. This behavior can lead to increased drug consumption as they attempt to cope with mental health challenges through substance abuse (25). Mental health issues can heighten susceptibility to addiction. Emotional distress and stress linked to conditions such as anxiety and depression may drive individuals to seek solace in drugs, potentially leading to rapid dependency (26). The data indicate a significant correlation between addiction and mental health disorders. More than 60% of those struggling with addiction also experience co-occurring mental health issues. This high rate of comorbidity suggests that the presence of one condition may exacerbate the other, potentially resulting in more severe substance abuse (7).

Another study by Mardani et al. showed that the presence of an addicted colleague and hard, exhausting work are the most important factors causing psychological problems in individuals (27). These observations are consistent with the findings of the present study, which indicate that addicts with depression and anxiety exhibited a significantly higher frequency of drug use than those without psychiatric disorders. Therefore, recognizing these factors underscores the critical need for integrated treatment strategies that concurrently address addiction and mental health disorders. Such approaches can mitigate the severity of substance use and enhance the overall outcomes for individuals facing these co-occurring challenges. In total, only one-third of addicts used a single type of drug, whereas the remaining two-thirds used two or more drugs simultaneously. The results of the present study indicated that the number of drugs consumed was higher among service and technical workers, as well as among individuals without insurance and those with rural insurance. Additionally, the insurance status among addicts with different levels of drug consumption showed a significant statistical difference.

People with different occupations have different types of insurance, and those without insurance likely do not have stable jobs. The relationship between job stability and drug addiction is influenced by several factors, such as financial stability, social support, work environment, job satisfaction, and predictability and routine. Steady employment offers income and financial stability, which can alleviate stress and anxiety — common factors that contribute to drug misuse (28). These positions typically provide a structured workplace environment, complete with employee support programs, health coverage, and a sense of belonging, all of which help reduce the likelihood of addiction. Increased job satisfaction and feelings of purpose associated with long-term roles often result in improved mental well-being and decreased substance use (29). Enduring professional relationships with coworkers and managers in permanent positions create a support system for managing stress and avoiding drug abuse. Consistent schedules and routines found in stable jobs promote healthier lifestyles and diminish the urge to use drugs. On the other hand, temporary work is often linked to job uncertainty, fluctuating incomes, and a lack of benefits, which can increase stress levels and the risk of substance abuse (30). The unpredictable nature of short-term employment makes it challenging to maintain a balanced life and seek assistance when necessary.

One study has shown that addicts who have a stable job and a consistent income after addiction treatment are less prone to relapse than other addicts undergoing treatment (18). Additionally, in the study by Ghorbani et al., people with permanent jobs were less likely to become addicted to drugs than those with temporary jobs (22). Addiction related to prescription drugs, especially opioids such as codeine and benzodiazepines, should be closely monitored because higher insurance coverage for these drugs may lead to increased abuse. The results of the study on job frequency at the onset of addiction showed that 2.9% of the participants were unemployed, and this percentage increased to 8.1% in their current jobs, indicating the impact of addiction on rising unemployment rates and job loss (18). Henkel demonstrated that substance use increases the likelihood of unemployment and decreases the chances of finding and maintaining a job (31). In our study, there was no significant relationship between the type of drug abuse and occupation. A study on patients referred for addiction treatment concluded that unemployment increased drug use. The researchers found that for each unit increase in the unemployment rate, opioid addiction rose by 9% (32).

A weak negative correlation was observed between age, age at the onset of addiction, age at first drug use, and the amount of drug use per month with the number of drugs consumed. Shaw et al.'s study indicated that age is a protective factor against drug use, with older individuals being less likely to use drugs (33). Our study also found that as the age of addicts increased, the number of drugs used decreased. One of the main limitations of our study was its cross-sectional design, which restricted the ability to draw definitive causal conclusions. Additionally, due to limited funding, the research focused solely on male participants from a single addiction treatment center, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations, including females and individuals from diverse geographical or cultural backgrounds. The reliance on self-reported data from the MAP Questionnaire and the job conditions checklist further adds to the limitations.

Moreover, the study did not employ advanced statistical methods to control for potential confounding variables. While we used univariate and bivariate statistical tests (such as chi-square, t-test, and Pearson/Spearman correlations) to examine associations, we did not conduct multivariable analyses like logistic or linear regression, which could have better accounted for confounders such as age, psychiatric disorders, and job-related factors. Consequently, observed associations should be interpreted with caution, and future research should encompass a broader timeframe, multiple locations, and larger patient populations, incorporating multivariate statistical approaches to rigorously explore these relationships and adjust for potential confounders.