1. Background

Hypersexuality (HS) is characterized by unsuccessful efforts to control sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors, often arising from distress or boredom (1). Manifestations include compulsive pornography use, frequent masturbation, multiple partners, and intrusive sexual thoughts (2). The prevalence of HS is estimated to be between 2% and 6%, with higher rates in men, particularly gay men, and sex offenders (3). The HS can be conceptualized as an obsessive-compulsive disorder where obsession begins with pleasure or satisfaction, and compulsion continues it (4). Early experiences and dysregulation of emotional and cognitive systems correlate with hypersexual behaviors (5), with recent research focusing on experiential avoidance (EA) and executive function deficits (EFDs) (6).

The EA involves changes in unpleasant emotions that trigger avoidance responses (7). From acceptance and commitment theory, it includes cognitive avoidance and emotional avoidance (8). These components are initially reinforced by reducing cognitive suffering but eventually disrupt life with unpleasant emotions and thoughts (9). The EA significantly correlates with EFDs, which manage thoughts and behavior through working memory, cognitive flexibility, and attention control (10).

The EFDs are a core vulnerability in HS (11). The EFDs involve impairments in working memory, inhibitory control, and decision-making (10). Neuroimaging shows altered activity in brain regions responsible for impulse regulation in individuals with compulsive sexual behaviors (12). High executive dysfunction correlates with steeper delay discounting and difficulty inhibiting responses to sexual cues (13). Few models have integrated EFDs and EA to explore their interaction in HS symptoms where self-compassion (SC) shows protective effects (14).

The SC was first defined by Neff as the concept of paying attention, recognizing, and clearly seeing unpleasant feelings, and it is defined by the three main components of self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness (15). The SC has been consistently linked to various indicators of psychological well-being, including reduced psychopathology and improved emotional resilience (16). Phillips et al. demonstrated that SC buffers the shame-HS cycle by promoting alternative self-relational strategies and reducing the propensity for sexual aggression among those high in shame but low in SC (17). However, some research has noted that SC’s protective effects can vary by context and measurement: For instance, Bates et al. found that SC’s inverse relationship with social anxiety depended on stress levels (18), and Yela et al. reported that reductions in EA, rather than SC itself, primarily drove improvements in well-being following mindfulness and SC training (19). These mixed findings underscore the importance of examining SC’s mechanisms and boundary conditions before positioning it as a universal buffer in HS.

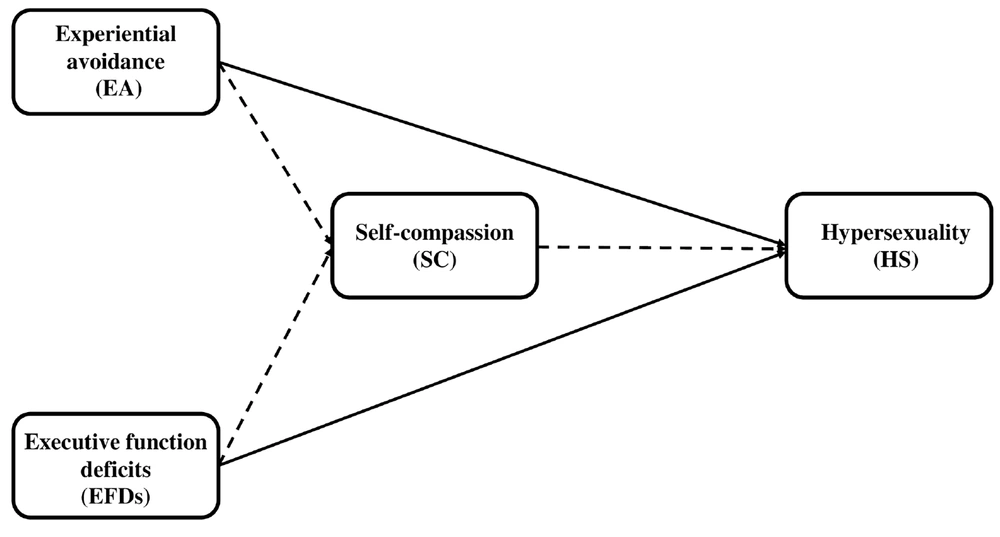

Drawing on theoretical and empirical literature (Figure 1), an integrated model is presented in which EA and EFDs both contribute to hypersexual behavior through intertwined cognitive-emotional pathways. The EFDs were linked to poorer inhibitory control and less effective long-term consequence evaluation (20), while EA perpetuates maladaptive coping by suppressing aversive internal states (21). The SC is conceptualized as a mediator that can weaken these effects by fostering mindful awareness, reducing self-judgment, and enhancing emotional regulation, potentially disrupting the cycle underlying HS (22).

2. Objectives

While interventions target hypersexual behavior, they often lack clarity about change mechanisms. This study has two aims: To test a mediation model where EA and EFDs influence hypersexual behavior through SC as a mediator, and to develop an eight-session intervention protocol targeting these components. The SC is expected to improve emotional regulation and cognitive control, interrupting how avoidance and executive dysfunction increase hypersexual risk. The intervention protocol's design links each component to specific pathways in our model to enhance theoretical understanding and treatment effectiveness.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Implementation Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 370 single students at Bojnord city, Iran, during 2023 - 2024. Using the Krejcie and Morgan table and G*power software, a sample size of 400 was determined (23), with 10% added for exclusions. Quota sampling was used based on Bojnord University's faculties: Engineering, humanities, basic sciences, and arts, considering each faculty's proportion of the 4,714 total students. Participants had to provide informed consent, be over 18, unmarried, and free from psychiatric or addictive drugs for six months. Students were excluded if they left over 20% of items unanswered, showed biased responses, or damaged questionnaires, resulting in 30 exclusions.

After validating the study's hypothesis, an integrated intervention protocol for hypersexual behaviors was developed, incorporating findings from current and previous research. The protocol drew from therapeutic approaches including acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (24), emotion-focused therapy (EFT) (25), behavioral skill training (26), Barkley behavioral training (27), unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment (28), Hackmann cognitive therapy (29), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) (30), attention network training (31), mindful self-compassion program (MSC) (32), and compassion-focused therapy (CFT) (33). Six psychotherapists specializing in hypersexual behavior evaluated the protocol's content validity through the Content Validity Ratio (CVR) and the Content Validity Index (CVI) assessments, until full validity was achieved.

3.2. Research Tools

In this research, the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI), the short form of the Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (BEAQ), the Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale (BDEFS), and the Self-compassion Inventory-Short Form (SCI-SF) were used for data gathering.

3.2.1. The Hypersexual Behavior Inventory

The HBI was designed by Reid et al. and includes 19 self-report questions that examine hypersexual behavior in three dimensions: Control, consequence, and coping (34). The HBI ranks responses on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always), with higher scores indicating more hypersexual behavior (34). Cronbach's alpha coefficient and factor analysis of the HBI have been confirmed in different studies (35). In Iran, Shalchi and Seyed Hashemi showed Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the whole scale to be 0.9, and for the three subscales of control, consequence, and coping to be 0.82, 0.8, and 0.86, respectively (36). In the present sample, Cronbach’s α for the HBI was 0.87.

3.2.2. The Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire

The BEAQ is a short version of the MEAQ by Gamez et al. (37). The BEAQ has six subscales and 15 items on a 1 - 6 Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher EA (37). Gamez et al. reported Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.86, 0.8, and 0.85, with correlations of 0.74 and 0.75 with AAQ-II and MEAQ scales (37). In Iran, Cronbach's alpha coefficients ranged between 0.68 - 0.89, with confirmed differential validity and goodness-of-fit indices (38). The present sample Cronbach's α was 0.85.

3.2.3. The Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale

The BDEFS by Barkley contains 89 items across five subscales: Planning, self-organization/problem solving, impulse control, self-motivation, and emotion regulation (39). Responses range from 1 ("never") to 4 ("often"), with higher scores indicating greater dysfunction (39). The Latin version's validity has been confirmed (40). In Iran, Mashhadi et al. found Cronbach's alpha above 0.8 for all subscales, with good model fit (41). The present sample Cronbach's α was 0.82.

3.2.4. The Self-compassion Inventory-Short Form

The SCI-SF by Raes et al. comprises 12 items measuring SC versus self-judgment, common humanity versus isolation, and mindfulness versus over-identification (42). Items use a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater SC (42). The scale shows a 0.97 correlation with its long form and 0.92 test-retest reliability (42). In Iranian populations, Khanjani et al. found Cronbach's alpha of 0.86 for the total score and 0.79, 0.71, and 0.68 for components, with 0.9 retest reliability (43). The present sample Cronbach's α was 0.84.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics to summarize demographic characteristics and key variables. Structural equation modeling (SEM) examined direct and indirect effects among exogenous, endogenous, and mediating variables (44). Models used covariance matrices with relationships formalized through regression equations. Content analysis was conducted for quantitative findings and therapeutic intervention components. The intervention's content validity was assessed through expert evaluations using CVR and CVI. AMOS-23 was used for SEM modeling and SPSS (version 26) for descriptive information.

4. Results

The frequency and mean of demographic information and main research variables for participants are shown in Table 1. Prior to analyzing primary hypotheses, normality, multicollinearity, and homogeneity of variances were examined. Results indicated the data were suitable for statistical tests. The Pearson correlation coefficient assessed relationships between variables (Table 2). Results showed significant positive relationships between HS, EA, and EFDs, while negative relationships were observed with compassion components (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness). Additionally, negative relationships existed between EA and compassion components, as well as between EFDs and compassion components.

| Variables | No. (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 21.02 ± 1.33 | |

| 19 - 20 | 109 (29.38) | 19.67 ± 0.12 |

| 21 - 22 | 105 (28.35) | 21.88 ± 0.09 |

| 23 - 24 | 111 (30.15) | 23.71 ± 0.22 |

| > 24 | 45 (12.12) | 25.88 ± 0.82 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 146 (39.4) | - |

| Female | 224 (60.6) | - |

| Education department | ||

| Engineering | 111 (30) | - |

| Humanities | 170 (45.95) | - |

| Basic sciences | 33 (8.92) | - |

| Arts | 56 (15.13) | - |

| HS | - | 46.64 ± 12.25 |

| EA | - | 54.27 ± 10.75 |

| EFDs | - | 210.77 ± 40.14 |

| SC | - | 32.77 ± 4.98 |

| Self-kindness | - | 12.77 ± 2.29 |

| Common humanity | - | 11.74 ± 2.39 |

| Mindfulness | - | 12.94 ± 2.27 |

Abbreviations: HS, hypersexuality; EA, experiential avoidance; EFDs, executive function deficits; SC, self-compassion.

Abbreviations: EA, experiential avoidance; EFDs, executive function deficits; HS, hypersexuality.

a Significance at the 0.01 level.

The structural model was evaluated using structural equation modeling, positing that EA and EFDs predict HS directly and indirectly through SC mediation. The model's fitting indicators showed a good fit with the collected data (Table 3). Path coefficients (Table 4) indicated hypersexual behavior was significantly influenced by EA and EFDs, with SC significantly mediating these relationships.

| Fit Indices | Observed Value | Cut-off Point | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/ df | 3.14 | < 5 | Optimal |

| RMSEA | 0.07 | < 0.08 | Optimal |

| AGFI | 0.93 | > 0.9 | Optimal |

| CFI | 0.97 | > 0.9 | Optimal |

| GFI | 0.91 | > 0.9 | Optimal |

Abbreviations: RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; AGFI, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index.

| Paths | B | S.E | Β | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EA → HS | 0.287 | 0.063 | 0.251 | 0.001 |

| EFDs → HS | 0.109 | 0.015 | 0.357 | 0.001 |

| EA → SC | -0.046 | 0.009 | -0.436 | 0.001 |

| EFDs → SC | -0.009 | 0.002 | -0.332 | 0.001 |

| SC → HS | -0.381 | 0.107 | -0.353 | 0.001 |

| EA → SC → HS | - | - | 0.154 | 0.001 |

| EFDs → SC → HS | - | - | 0.117 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: EA, experiential avoidance; HS, hypersexuality; EFDs, executive function deficits; SC, self-compassion.

The study developed an integrated intervention protocol for hypersexual behaviors, incorporating elements targeting executive functions, SC, and EA. An eight-session protocol was developed based on variables' influence and content validity. Using the Lawshe table, the minimum acceptable value for six experts was 0.99 (α = 0.05) (45). After revisions, the CVR was confirmed (= 1), and the CVI was validated for all sessions. Table 5 presents therapeutic components, content, and CVI for each session.

| Sessions | Therapeutic Component | Content | CVI |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | Communication, psychological needs and emotions | The importance of confidentiality and trust; training to recognize emotions, distinguish pleasant from unpleasant ones, connect emotions with body and psychological needs | 1 |

| Second | The sexual patterns of avoiding emotion, the sexual history, the chain of sexual temptation | Explaining sexual behavior's role in soothing and avoiding unpleasant emotions; examining emotional blockages and symbolization; investigating auditory and visual sexual memories (analysis of trauma); examining chain of temptation: Analysis of four recent sexual behavior situations; recognizing triggers: Identifying cues that initiate sexual urges and becoming aware to anticipate and avoid these scenarios | 1 |

| Third | Executive functions | Impulse control exercises: (A) 15-minute activity to postpone impulses and (B) 5-minute mindful awareness practice; exercise negative consequences reminder for 5 minutes during delay; daily assignment: Negative consequences reminder | 0.83 |

| Fourth | Behavior replacement, the neural pathway of self-inhibition and attention | Adaptable substitution behavior exercise: List person's behavioral preferences like favorite food and activities, prioritizing substitutions in written form; adaptable substitution behavior exercise: List behavioral preferences, prioritize substitutions in writing, perform in second 15 minutes after temporal delay; mental imaging exercise: Practice 10 - 15 minutes daily for 4 weeks, visualizing temptation situations where client uses visualization to control impulses instead of yielding to them | 0.83 |

| Fifth | The tDCS, concurrent behavioral exercises | The tDCS in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: Anode in F3 area, cathode in F4 area, 2 mA intensity for 30 minutes, 12 sessions (3 per week); summarizing text's key points during first 15 minutes of tDCS; mental imaging of temptation during second 15 minutes of tDCS | 0.83 |

| Sixth | Getting to know the self | Teaching dialectical nature of self: Blaming, anxiety-giving, and compassion-giving parts; seven-part compassion exercise: Teaching SC concepts including self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness | 0.83 |

| Seventh | Regulating and correcting the anxious and blaming self | Relaxation exercise: Managing uncomfortable feelings and sexual arousal; two chairs dialogue: Becoming conscious of inner conflicts and mixed feelings for integration | 0.83 |

| Eighth | Empowering SC | Self-interruption dialogue: Fostering SC through conversation between conflicting aspects; imaginary confrontation exercise: Confronting inner child's vulnerabilities through compassionate behavior | 1 |

Abbreviations: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation; SC, self-compassion.

5. Discussion

The present study had two main objectives. The first objective was to assess the adequacy of the proposed model that explored the relationship between EA and EFDs in hypersexual behavior, with the mediation of SC, which was evaluated through complementary hypotheses. The second objective involved the design and establishment of content validity of an integrated intervention protocol grounded in these variables.

The results established a significant positive association between EA and HS, corroborating prior research (5, 46). Wetterneck et al. (46) reported a similar link between EA and problematic internet pornography use, proposing that avoiding distressing internal experiences may propel individuals toward maladaptive sexual behaviors as a coping strategy. This study extends that perspective by situating EA within a broader model that includes EFDs and SC, revealing a more comprehensive picture of HS’s underpinnings.

Notably, a significant negative relationship emerged between EA and SC, aligning with Wang et al. (47), who found SC to mitigate EA’s adverse effects in adolescents. Within the framework of ACT, SC appears to counter EA’s rigidity by promoting mindfulness and compassionate self-engagement (48), suggesting its potential as a therapeutic lever to reduce EA and, by extension, HS.

Equally compelling is the positive association between EFDs and HS, consistent with findings from Rosenberg et al., Dominguez-Salas et al., and Montgomery-Graham (49-51). These studies highlight how impairments in executive functions — such as impulse control, decision-making, and working memory — predispose individuals to atypical sexual behaviors. This research advances that understanding by demonstrating a negative link between EFDs and SC, as supported by Jacobs (52), who noted that higher SC correlates with improved executive functioning. This interplay implies that bolstering SC could enhance cognitive flexibility and emotional regulation, offering a dual benefit in addressing EFDs and HS.

Central to this study is the confirmation that SC mediates the relationship between EA, EFDs, and HS. The data suggest that elevated EA and EFDs diminish SC, which in turn intensifies HS. This mediation aligns with Kotera and Rhodes (53), who identified SC as an emotion regulator that reduces anxiety and shame — emotions that might otherwise fuel hypersexual tendencies. By integrating these variables into a cohesive model, this research elucidates the cognitive-emotional pathways driving HS and underscores SC’s protective role, providing a nuanced framework for both theory and intervention.

The development and validation of an integrated intervention protocol mark another key contribution. Expert evaluation confirmed its content validity, affirming the relevance of its multi-component design, which draws from evidence-based approaches (24-33). These modalities were deliberately chosen and arranged based on an integrated cognitive-emotional regulation framework, where each component targets a specific mechanism involved in hypersexual behavior. For example, they aim to foster psychological flexibility to reduce EA (8, 25, 28, 33), cultivate adaptive emotion processing (25, 32, 33), interrupt shame-driven coping (28, 29), and enhance prefrontal executive control to improve impulse inhibition (30), enhance attention (31), and ultimately behavior (26, 27). Overall, this multi-component approach addresses complementary cognitive, affective, and neurophysiological processes within a coherent, theory-driven intervention model. Its progressive structure — beginning with emotional recognition, incorporating innovative techniques, and culminating in SC-focused sessions — reflects a theoretically sound approach. It is important to note that the long-term implementation of these strategies and cognitive-behavioral techniques may necessitate participation in group therapy, support systems, and lifestyle improvements for individuals with HS.

5.1. Conclusions

This study confirms that EA and EFDs were associated with hypersexual behavior, with SC mediating these associations through emotional regulation and impulse control. Expert evaluation established the content validity of our eight-session protocol within an integrated cognitive–emotional regulation framework. However, as this intervention has only undergone content validation, its clinical efficacy remains untested. Future research should implement randomized controlled trials to determine the protocol's impact, use longitudinal assessments to clarify causal mechanisms, and assess its applicability across populations. Such studies are essential to translate our framework into evidence-based treatment for hypersexual behavior.

5.2. Limitations

This study had limitations. The sample was from one university in Iran, limiting generalizability. A complete psychiatric examination was not performed on participants; therefore, psychiatric disorders may have affected the results.

5.3. Suggestions

The EFDs and HS were assessed by self-report, which could involve response bias. Future studies should modify evaluation methods and examine the pattern of variables in larger, diverse samples.