1. Background

Substance use tendency is one of the fundamental challenges of the contemporary world. Due to its detrimental effects on the development and prosperity of societies, it has become a serious and alarming threat, ranking among the most critical public health issues on a global scale (1). Addiction to narcotic substances is a complex disease with biological, psychological, and social dimensions. A variety of factors contribute to its development, and through their interaction, they pave the way for the inclination toward substance use and eventual dependence (2). Substance use tendency encompasses an individual’s beliefs and attitudes toward a specific substance and reflects their perceptions of the potential positive or negative consequences of its use (3).

Drug use, especially among youth and alongside other social harms, worsens its impact. Despite university efforts, usage is rising, with 36% of people aged 16 - 59 affected. Contributing factors include social, economic, and psychological challenges, making it a serious social concern (4). Studies have shown that adolescents who engage in self-harm are more likely to face interpersonal issues and substance misuse later in life (5). These behaviors, whether direct (e.g., cutting) or indirect (e.g., substance misuse), are often maladaptive strategies to cope with emotional distress and are linked to substance use tendency (6). Regardless of suicidal intent, they reflect an attempt to manage psychological pain (7).

Cutting the skin with sharp objects is the most common form of self-injury, but self-harm includes a range of behaviors such as burning, scratching, hitting oneself, interfering with wound healing, skin-picking, trichotillomania, substance misuse, and self-poisoning (8). Beyond personal harm, this issue carries major social consequences. Its rise among adolescents may lead to chronic illness and economic loss. Research also shows a clear link between adolescent self-harm and later substance use tendency. Leino et al. (9) found a positive correlation between self-injury scores and drug addiction. Similarly, Sarkar et al. (10) concluded that self-harming behaviors are a notable concern among patients with substance use disorders.

Given the rising trend of self-injury among youth, a concurrent increase in high-risk behaviors like substance misuse is anticipated. While a strong link between self-harm and substance use tendency is documented, research suggests this relationship may be partly mediated by other variables. This raises the question: Through what mechanisms do self-harming behaviors influence substance use tendency?

One construct that has attracted increasing scholarly attention in recent years is self-compassion. Self-compassion, as a protective personality trait, helps individuals accept negative experiences and self-criticism, thereby reducing anxiety and depression and lowering the risk of substance use (11). Self-compassion is the practice of responding to personal pain and challenges with kindness and understanding. It helps individuals face difficulties more effectively and consists of three key elements: Self-kindness (being gentle with oneself), common humanity (recognizing that everyone makes mistakes), and mindfulness (maintaining balanced awareness of the present moment) (12).

Lacking self-compassion and low self-esteem may drive individuals to use substances for emotional relief, but this short-term coping strategy can worsen issues and lead to dependence. Shahin et al. (13) demonstrated a significant negative relationship between self-compassion and substance use.

Given the psychological, cognitive, and emotional harms caused by substance use and its detrimental effects on social and familial structures, it is essential to conduct fundamental studies and extensive research aimed at preventing substance use tendency. While some previous studies have examined the relationships among the aforementioned variables, no research was found that specifically investigated the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between self-harming behaviors and substance use tendency. This highlights a clear gap in the literature. Accordingly, the present study was conducted with the aim of proposing a model of substance use tendency based on self-harming behaviors, with the mediating role of self-compassion.

2. Objectives

The present study investigated how self-injurious behaviors predict substance use tendency among university students and examined the mediating role of self-compassion. Using a structural model, it aimed to clarify the emotional and behavioral pathways contributing to substance-related risks and addressed a gap by exploring the link between self-harm, self-compassion, and substance use tendency.

3. Materials and Methods

The research method used in this study was correlational, employing structural equation modeling (SEM) due to the nature of the topic. The statistical population of this study consisted of all students at Urmia University during the 2023 - 2024 academic year (n = 13,267). From this population, a sample of 350 students was selected through multistage random sampling. To this end, three faculties — faculty of literature and humanities, faculty of engineering, and faculty of basic sciences — were randomly chosen as the first clusters out of the university’s 11 faculties.

3.1. Procedure

Data were collected through public calls on virtual platforms and faculty bulletin boards. After explaining the study’s goals, confidentiality, and the need for honest responses, questionnaires were distributed and returned to the research representative. Data analysis was performed using SPSS v22 and AMOS, employing descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation tests.

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Addiction Tendency Questionnaire

The Addiction Tendency Questionnaire, developed by Weed et al. (14) and validated in Iran by Zargar et al. (15), contains 36 main items and 5 lie detection items, measuring two factors: Active and passive readiness. Items are scored from 0 to 3, with some reverse-scored. Validity was confirmed through multiple methods, with a construct validity correlation of 0.45 and Cronbach’s alpha reported as 0.90 (14); in this study, it was 0.75, indicating good reliability.

3.2.2. Self-harm Behaviors Questionnaire

This 22-item questionnaire, developed by Sansone et al., measures both direct (e.g., cutting, suicide attempts) and indirect (e.g., substance misuse, risky sexual behavior) self-harm (16). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 - 5). The tool shows good convergent validity with borderline personality, depression, and childhood abuse. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74 (17), and 0.77 in this study, indicating good reliability.

3.2.3. Self-compassion Scale Short Form

The 12-item Self-compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF) by Raes et al. (18) includes six bi-dimensional factors and is scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with some items reverse-scored. Shahbazi et al. (19) confirmed its acceptable content, face, and criterion validity. Subscale Cronbach’s alphas ranged from 0.77 to 0.92, and overall reliability in this study was 0.77, indicating good reliability.

4. Results

The findings indicated that among the participants in the present study, 112 individuals (36.36%) were from the faculty of engineering, 98 individuals (29.44%) from the faculty of basic sciences, and 140 individuals (39.20%) from the faculty of humanities. Regarding age distribution, 206 participants (57.68%) were between 20 and 25 years old; 96 participants (26.88%) were between 26 and 30 years old; 32 participants (8.96%) were between 31 and 35 years old; and 16 participants (4.48%) were above 35 years of age. In terms of gender, 126 participants (35.28%) were male and 224 participants (64.72%) were female.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Distribution Checks

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Since all skewness and kurtosis values were below 2, the normality assumption for structural modeling was met.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| Tendency to substance use | |||

| Active readiness | 51.13 ± 7.22 | -0.45 | -0.55 |

| Passive readiness | 39.88 ± 4.54 | -0.38 | -0.77 |

| Tendency to substance use | 90.33 ± 6.42 | -0.23 | -0.28 |

| Self-injurious behaviors | |||

| Direct behavior | 20.19 ± 2.99 | 0.52 | 0.37 |

| Indirect behavior | 39.44 ± 3.03 | 0.38 | 0.85 |

| Self-injurious behaviors | 60.55 ± 5.55 | -0.17 | -0.45 |

| Self-compassion | |||

| Kindness vs. self-judgment | 14.11 ± 1.85 | 0.66 | 0.86 |

| Experiences vs. isolation | 15.05 ± 2.02 | 0.09 | -0.27 |

| Mindfulness vs. over-identification | 13.88 ± 2.33 | 1.01 | 0.16 |

| Self-compassion | 43.03 ± 4.66 | -0.73 | -0.11 |

4.2. Bivariate Correlations

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of the study variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active readiness | 1 | ||||||||

| Passive readiness | 0.542 a | 1 | |||||||

| Tendency to substance use | 0.583 a | 0.522 a | 1 | ||||||

| Direct behavior | 0.499 a | 0.502 a | 0.542 a | 1 | |||||

| Indirect behavior | 0.542 a | 0.499 a | 0.542 a | 0.603 a | 1 | ||||

| Self-injurious behaviors | 0.519 a | 0.495 a | 0.505 a | 0.613 a | 0.600 a | 1 | |||

| Kindness vs. self-judgment | -0.622 a | -0.542 a | -0.623 a | -0.401 a | -0.503 a | -0.389 a | 1 | ||

| Experiences vs. isolation | -0.591 a | -0.587 a | -0.581 a | -0.387 a | -0.413 a | -0.394 a | 0.404 a | 1 | |

| Mindfulness vs. over-identification | -0.599 a | -0.590 a | -0.562 a | -0.412 a | -0.466 a | -0.445 a | 0.519 a | 0.486 a | 1 |

| Self-compassion | -0.601 a | -0.563 a | -0.585 a | -0.398 a | -0.463 a | -0.422 a | 0.448 a | 0.555 a | 0.602 a |

a P > 0.001.

As observed in Table 2, significant reciprocal relationships were found among the study variables. Before analysis, SEM assumptions were checked. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that all variables were normally distributed (P ≥ 0.05). The Durbin-Watson value was 1.41, confirming no autocorrelation in residuals. Multicollinearity was also ruled out, as tolerance values were near 1 and all VIFs were below 2.

4.3. Structural Equation Model-Mediation Analysis

To evaluate the model fit, several indices, including χ2/df, RMSEA, SRMR, CFI, GFI, TLI, and IFI, were calculated (Table 3). According to the recommended criteria (20), RMSEA values below 0.08 and SRMR values below 0.08, along with CFI, GFI, TLI, and IFI values above 0.90, indicate an acceptable model fit.

| Indicators | CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | PNFI | SRMR | RMSEA 95% CI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable range | 1 to 5 | > 0.90 | > 0.08 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.50 | > 0.08 | - | > 0.08 |

| Initial proposed model | 2.92 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.59 | 0.056 | (0.089 - 0.065) | 0.077 |

| Model fit | Fit | Poor model fit | Fit | Poor model fit | Poor model fit | Poor model fit | Fit | - | - | Poor model fit |

| Final modified model | 3.28 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.061 | - | 0.086 |

| Model fit | Fit | Fit | Fit | Fit | Fit | Fit | Fit | - | (0.098 - 0.078) | Fit |

In the final model, the RMSEA value was 0.086 (90% CI = 0.078 - 0.098) and the SRMR value was 0.061, both falling within the acceptable range. The CFI and GFI values were both 0.90, and the χ2/df ratio was 3.28. Although the RMSEA and CFI/GFI values are at the borderline of the acceptable threshold and not ideal, given the complexity of the model and the large number of latent and observed variables, these values remain within the range considered “acceptable” by many sources. Furthermore, the SRMR and other fit indices also confirmed the adequacy of the model fit.

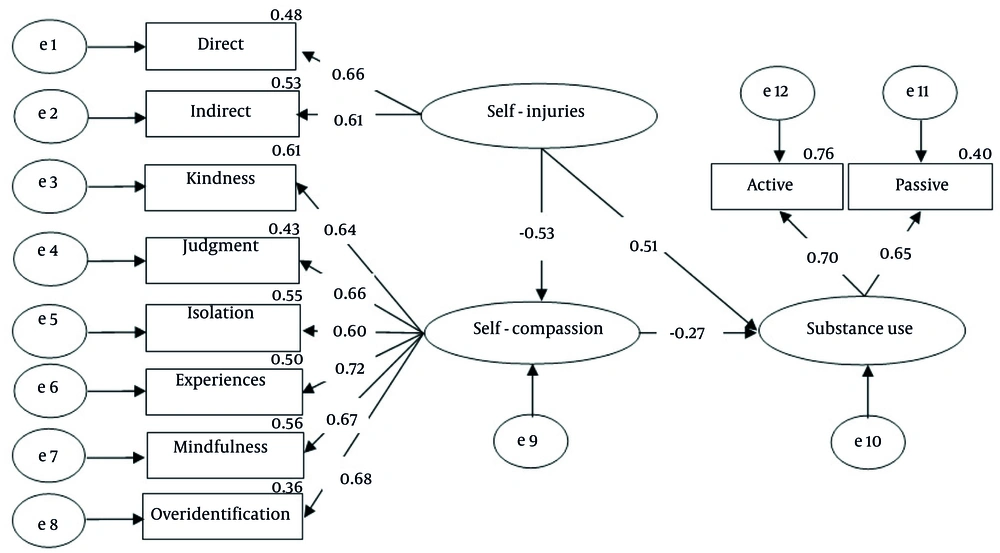

Following the initial estimation and examination of the modification indices in AMOS, the preliminary model was improved through limited modifications. These changes included adding correlations between the error terms of some indicators within the same construct and removing one non-significant path, both of which were theoretically and empirically justified based on previous research. After these adjustments, the fit indices improved, and the final model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data. The standardized path coefficients of the model are shown in Figure 1.

The results showed that the path coefficients related to the direct effects of the study variables are statistically significant, and the results of the bootstrap test in AMOS software with 2000 samples are presented in Table 4.

| Predictor Variables | Criterion Variables | B | SE | C.R | P | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-injurious behaviors | Tendency to substance use | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.001 | Confirmation |

| Self-injurious behaviors | Self-compassion | -0.53 | 0.056 | 0.39 | 0.001 | Confirmation |

| Self-compassion | Tendency to substance use | -0.27 | 0.49 | 0.63 | 0.001 | Confirmation |

The results presented in Table 5 show that the lower and upper bounds of the indirect paths between childhood trauma and self-injurious behaviors to substance use tendency through self-compassion do not include zero, indicating the significance of this indirect path.

| Predictor Variable | Mediator Variable | Criterion Variables | Resampling | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-injurious behaviors | Self-compassion | Tendency to substance use | 350 | 0.019 | 0.129 | 0.95 |

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to model substance use tendency based on self-harming behaviors, examining the mediating role of self-compassion among students at Urmia University. The results indicated a significant positive relationship between self-harming behaviors and substance use tendency, both directly and indirectly. In other words, higher levels of self-harming behaviors were significantly associated with an increased tendency toward substance use. For example, Chai et al. demonstrated that the risk of self-harm is significantly related to substance use (21).

Self-harming behaviors may predict substance abuse later in life by creating a cycle of negative emotions. To escape feelings like shame or depression, individuals may turn to substance use, increasing the risk of long-term dependence (22). Furthermore, engaging in self-harming behaviors can severely damage an individual’s self-esteem and sense of worth (23). In these situations, individuals may use substances to ease feelings of inadequacy or boost self-image, but while this may offer short-term relief, it can lead to addiction and long-term mental health issues (24).

Additionally, individuals who engage in self-destructive behaviors often face underlying psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, or emotional regulation disorders (25). Comorbid disorders can increase the tendency for substance use because individuals may use substances to self-medicate their symptoms (26). Therefore, individuals with self-harming behaviors may respond to the pleasurable and motivational effects of substances to alleviate the pain and emotional discomfort caused by these behaviors.

Another part of the findings indicates a significant negative relationship between self-compassion and substance use tendency. For instance, Shreffler et al. found that a lack of self-compassion leads individuals to a higher tendency for substance use, and individuals with substance use disorders often lack self-compassion (27). To explain the observed relationship between self-compassion and substance use tendency, the emotional regulation theory provides a useful framework (28). According to this theory, self-compassion plays a crucial role in emotional regulation and management by promoting adaptive strategies such as cognitive reappraisal and emotional acceptance (28). These strategies enable individuals to cope with distress without resorting to maladaptive methods like substance use. If self-compassion is not strengthened or developed, an individual may seek other ways, such as substance use, to control their negative emotions.

As self-compassion can increase resilience and improve coping mechanisms for stress (29), individuals who lack self-compassion are more likely to turn to substance use as a way to escape or neutralize their stress. Additionally, self-compassion boosts identity and self-esteem (30), further protecting against harmful coping strategies. Therefore, it can be concluded that self-compassion has a negative and inverse relationship with substance use tendency.

Another part of the study’s findings indicates a significant negative relationship between self-harming behaviors and self-compassion. For instance, Per et al. also found that self-compassion protects individuals from self-harming behaviors and suicidal thoughts (31). Individuals who engage in self-harming behaviors often struggle with low self-esteem, severe self-criticism, shame, hopelessness, and guilt, making them feel undeserving of self-compassion (32). Depression, a common outcome of self-harm, can intensify feelings of worthlessness and further reduce levels of self-compassion.

Regarding the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between self-harming behaviors and substance use tendency, self-compassion — defined as care, understanding, and kindness toward oneself — can interrupt this pathway through several psychological mechanisms (26, 33). First, self-compassion reduces self-criticism, shame, and feelings of worthlessness, which are common after self-harming behaviors and can trigger substance use as an escape strategy (34). By fostering a sense of unconditional self-worth, it removes a key emotional driver toward substance use (27).

Second, self-compassion enhances adaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as cognitive reappraisal and mindfulness, which help individuals face distress without resorting to harmful coping methods like substance use. Third, self-compassion promotes resilience and a stable sense of identity, enabling individuals to tolerate negative emotions and recover from emotional pain without engaging in further self-harm or substance use. Together, these mechanisms weaken the emotional and cognitive links between self-harming behaviors and substance use tendency, leading to healthier coping responses and reducing the likelihood of substance use.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed that self-harming behaviors are both directly and indirectly associated with substance use tendency, and self-compassion significantly mediates this relationship. In essence, individuals with higher levels of self-compassion are less likely to resort to substance use as a way to cope with emotional distress caused by self-harming behaviors. These results underscore the importance of incorporating self-compassion-focused strategies into psychological interventions aimed at preventing substance use, especially among adolescents and young adults.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, its correlational design does not allow for definitive conclusions about causal relationships. Second, the sample was limited to students from three faculties at Urmia University, which may not represent the broader student population. Additionally, controlling for background variables such as socioeconomic status, family environment, and other psychological factors was not possible. Furthermore, although the Substance Use Tendency Questionnaire used in this study has demonstrated prior validity, it may not fully capture newer substance use patterns such as vaping and synthetic drugs.

5.3. Recommendations

Given these limitations, future research should replicate this study with more diverse samples and in different settings to enhance the generalizability of findings. Experimental or longitudinal designs are recommended to better explore causal relationships. In this regard, employing updated and advanced measurement tools that cover emerging substance use behaviors is essential. Moreover, future studies should investigate self-compassion-based interventions through controlled trials to better understand their clinical efficacy and practical applications.

From a clinical perspective, interventions based on self-compassion represent an effective approach to reducing substance use tendencies and self-injurious behaviors. These interventions typically involve training in mindfulness skills, self-compassion exercises, and emotion regulation strategies that help individuals manage negative emotions in healthier ways. University settings, particularly through workshops, provide an appropriate environment for implementing these programs and promoting students’ mental well-being. Additionally, utilizing online platforms and group sessions can increase accessibility and enhance the effectiveness of such interventions.