1. Background

Child maltreatment is a significant global concern with profound and enduring health impacts. Recent estimates suggest that nearly one billion children aged 2 to 17 worldwide experience some form of abuse — whether physical, emotional, or sexual (1). Accurately determining the prevalence remains challenging due to variations in definitions, legal standards, and cultural perceptions across different countries (2). Notably, research increasingly recognizes that many children experience multiple types of victimizations simultaneously, a phenomenon known as polyvictimization (3). This multifaceted exposure often exacerbates adverse outcomes and is more common among vulnerable populations, such as children in the juvenile justice system or institutional care (4). Theoretical frameworks like the ecological system theory emphasize how victimization occurs across various levels — family, school, peer groups, and community — and how repeated or overlapping traumatic experiences can intensify psychological harm. Empirical studies support this, showing that exposure to multiple forms of trauma significantly increases the risk for mental health disorders, behavioral problems, and social difficulties (5). However, much of the existing research concentrates on individual types of maltreatment, often inflating their perceived effects and neglecting the cumulative burden of multifaceted victimization (6). Early childhood victimization — particularly when involving multiple forms — leaves lasting scars that extend into adulthood. Longitudinal studies consistently link childhood trauma to a range of adult issues, including anxiety, depression, risky behaviors, and chronic illnesses (7, 8). Survivors often face higher rates of substance use, mood disorders, PTSD, and physical conditions such as asthma and injuries (9, 10). Despite substantial evidence on long-term effects, research in non-Western settings — like Iran — is limited, especially concerning how cultural, social, and legal factors influence both victimization experiences and their recognition.

Children face victimization from various sources — peers, family members, teachers, or strangers — through different forms like physical violence, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, or cyberbullying. When experiencing multiple types across different settings, this is recognized as polyvictimization. Although earlier research often focused on specific abuse types, a growing body of evidence underscores the importance of understanding victimization as a complex, multifaceted phenomenon (11). Individuals already victimized are at higher risk for additional victimizations, creating a cycle that amplifies adverse outcomes (12). Prevalence rates of childhood victimization vary widely — ranging from 9% to 64% across countries (13). In Iran, existing studies mainly address bullying, sexual violence, and cyberbullying, often from legal perspectives, with limited focus on the broader scope and long-term consequences. Recent research indicates that over 99% of adults aged 18 - 45 reported experiencing at least one form of childhood victimization, with 92% reporting multiple victimizations (14). Despite these findings, research exploring the long-term impact of childhood polyvictimization on adult mental health in Iran remains scarce. Most studies focus on specific victimization types without considering their cumulative effects, limiting the development of culturally sensitive prevention and intervention strategies. Theoretical models, including trauma-informed frameworks, stress the importance of recognizing the interconnected and cumulative nature of victimization experiences to inform more effective responses. International research shows that individuals exposed to multiple victimization forms tend to experience more severe and prolonged mental health issues, such as increased anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems (12, 15). These early adverse experiences are also linked to adult health problems like substance abuse and mood disorders (9, 10, 16). Notably, nearly 96% of adults with intellectual disabilities report childhood victimization, underscoring its long-lasting impact (17).

Given the limited research in Iran, understanding how childhood polyvictimization relates to adult psychiatric symptoms is essential. Investigating these long-term effects can aid in developing targeted interventions to break the cycle of trauma. This study aims to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Juvenile Polyvictimization Questionnaire (JPQ) in the Iranian context and examine its relationship with psychiatric symptoms among adults.

2. Objectives

The objectives are threefold: To validate the JPQ for use within Iranian populations; to explore the association between childhood polyvictimization experiences and psychiatric symptoms in adulthood; and to lay the groundwork for future research and clinical applications aimed at developing targeted mental health interventions, ultimately supporting victims’ recovery and resilience across their lifespan.

3. Materials and Methods

This study aims to evaluate the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire (JVQ) and to explore its association with psychiatric symptoms. It is an applied, cross-sectional descriptive research project that adopts a psychometric approach, utilizing correlational analysis. The study population consisted of adults aged 18 to 45 years from across Iran who have internet access via virtual networks. We employed a psychometric approach using correlational methods to investigate the relevant variables. This nationwide sample encompassed individuals within this age range, all of whom had access to the internet. To determine an appropriate sample size, we used G*Power software for an F-test in multiple linear regression (fixed model, change in R2). Based on an estimated effect size (f2) of 0.063, with α = 0.05, the calculation indicated that a total of 573 participants would be sufficient. The results showed a non-centrality parameter (λ) of 36.099, a critical F value of 3.858, and an almost perfect statistical power (1-β) of 0.99997 — well above the recommended threshold of 0.80 (18). This suggests the sample size was more than adequate to detect the expected effects with high confidence, reducing the risk of type II error and strengthening the robustness of our findings. The study employed a non-random online sampling method to recruit a total of 573 Iranian adults aged 18 to 45 years, including 186 men, 417 women, and 10 individuals who did not disclose their gender. These participants had a mean age of 24.02 years (SD = 5.84). We acknowledge that this sampling approach may limit the generalizability of our findings and will address this limitation in the discussion. They completed the JVQ and the 25-item psychological symptoms checklist (SCL-25) within a two-week window.

The JVQ-revised version 2 (19) – has been updated to include multiple formats tailored to various research needs. Since this study did not involve interviews and focused on adults, we used the self-report Screen-Sum Version – adult retrospective form (SSV: ARF). This version includes 34 items where respondents answer "yes" or "no" to indicate whether they experienced specific victimization types. The items are divided into five subscales: (1) Conventional crimes, (2) child maltreatment, (3) sibling and peer victimization, (4) sexual victimization, and (5) witnessing or exposure to victimization. The total victimization score is the sum of these subscale scores. A detailed list of the items is provided in Table 1.

| Scales and Items | Crimes |

|---|---|

| Conventional crime | |

| 1 | Robbery |

| 2 | Personal theft |

| 3 | Vandalism |

| 4 | Assault with weapon |

| 5 | Assault without weapon |

| 6 | Attempted assault |

| 7 | Threatened assault |

| 8 | Kidnapping |

| 9 | Bias attack |

| Child maltreatment | |

| 10 | Physical abuse by caregiver |

| 11 | Psychological/emotional abuse |

| 12 | Neglect |

| 13 | Custodial interference/family abduction |

| Peer and sibling victimization | |

| 14 | Gang or group assault |

| 15 | Peer or sibling assault |

| 16 | Nonsexual genital assault |

| 17 | Physical intimidation by peers |

| 18 | Relational aggression by peers |

| 19 | Dating violence |

| Sexual victimization | |

| 20 | Sexual assault by known adult |

| 21 | Sexual assault by unknown adult |

| 22 | Sexual assault by peer/sibling |

| 23 | Forces sex (including attempts) |

| 24 | Flashing/sexual exposure |

| 25 | Verbal sexual harassment |

| 26 | Statutory rape and sexual misconduct |

| Witnessing and indirect victimization | |

| 27 | Witness to domestic violence |

| 28 | Witness to parent assault of sibling |

| 29 | Witness to assault with weapon |

| 30 | Witness to assault without weapon |

| 31 | Burglary of family household |

| 32 | Murder of family member or friend |

| 33 | Exposure to random shootings, terrorism, or riots |

| 34 | Exposure to war or ethnic conflict |

3.1. Symptom Checklist-25

The SCL-25 evaluates seven psychological symptom domains: Psychoticism, somatization, anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, phobia, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Respondents rate each of the 25 items on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). Higher scores reflect greater psychological distress, while lower scores indicate better mental health (20). Subscale scores are calculated as the mean of relevant items, and individuals in the top 30% are considered to have prominent psychiatric symptoms. The SCL-25 has demonstrated high reliability with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.71 to 0.95 across subscales (20).

3.2. Research Procedure

The study received ethical approval under the code of IR.USWR.REC.1401.112. Conducted in two main phases, the first involved translating and culturally adapting the JVQ. Guided by established protocols for cross-cultural measurement validation (21), the process included a three-step translation procedure. Initially, two native Persian-speaking psychologists fluent in English translated the JVQ into Persian, which was then compared and synthesized into a single version (JVQ-1). This draft was reviewed by two experienced professionals in psychological assessment who proposed modifications to ensure cultural relevance, resulting in the Persian version (JVQ-2). Next, an undergraduate student of English independently back-translated JVQ-2 into English, and a translation agency in Tehran translated this back into Persian, producing JVQ-3. A bilingual professor reviewed JVQ-3, offering grammatical and lexical suggestions, culminating in JVQ-4. Finally, two native English-speaking researchers verified that JVQ-4 maintained semantic and conceptual fidelity to the original instrument. Following ethical approval, we advertised participation through various online platforms — such as LinkedIn, Twitter, ResearchGate, WhatsApp, Telegram, and Instagram — detailing the study’s aims. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were adults aged 18 to 45, and the questionnaires were hosted online via Porsline. Participants were assured of confidentiality and the right to withdraw at any time. They completed the JVQ and the SCL-25 within two weeks. To clarify, the second goal — exploring the association between childhood polyvictimization experiences and adult psychiatric symptoms — relies on analyzing the data collected through the JVQ and the accompanying psychological SCL-25. Specifically, we conducted statistical analyses such as correlational and regression models to identify whether and to what extent childhood victimization patterns predict the severity or types of psychiatric symptoms in adulthood. This approach helps us understand the long-term mental health impacts of polyvictimization. As for the third goal — providing evidence-based insights to guide targeted interventions — we plan to interpret these findings within a clinical context, aiming to identify specific victimization experiences that warrant focused mental health support.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize sample demographics and questionnaire scores. The validity of the JVQ was examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS to assess the instrument’s factorial structure, while reliability was evaluated via Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. Test-retest reliability was also considered if relevant. For the SCL-25, scores were categorized based on the upper and lower 30% thresholds to identify individuals with significant psychiatric symptoms. To explore the relationship between victimization and psychiatric symptoms, Pearson correlation analyses and multiple regression models were employed, with significance set at P < 0.05. All statistical tests aimed to ensure the instrument’s robustness and to clarify the associations between childhood victimization experiences and mental health outcomes. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26 and AMOS.

4. Results

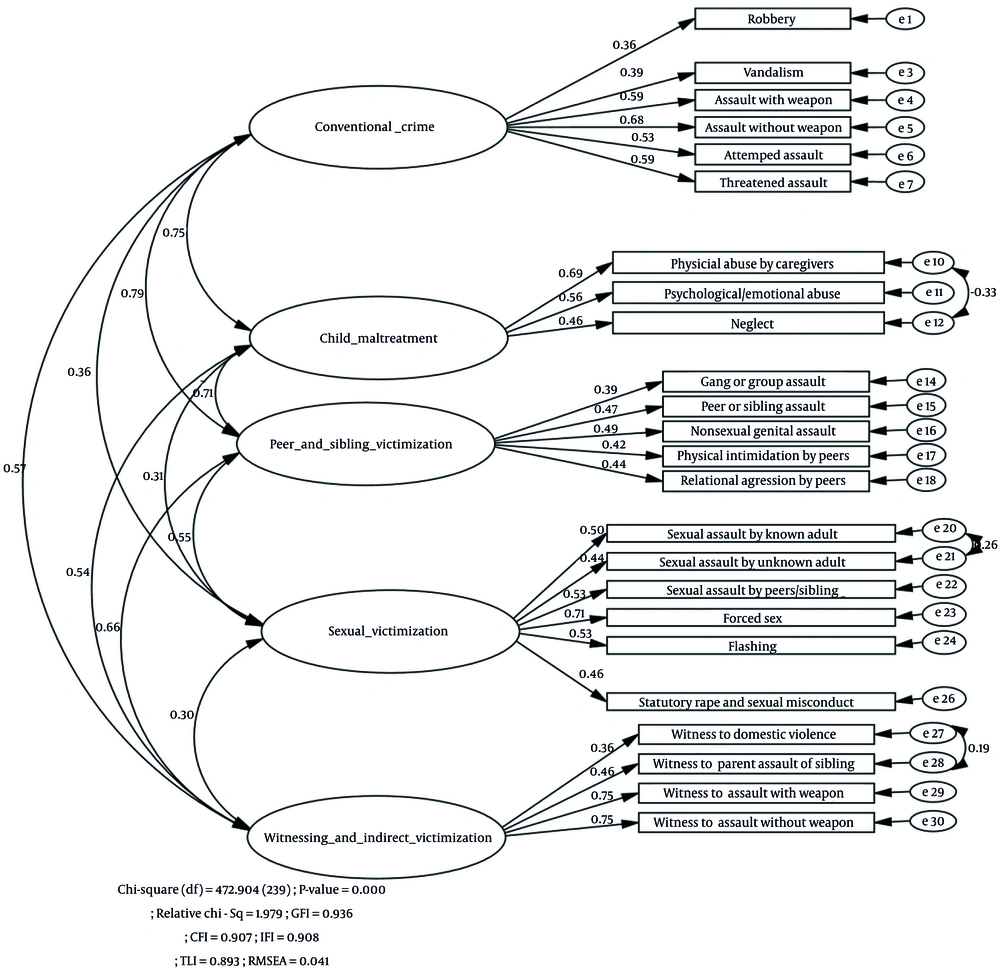

To assess the validity of the JVQ, a construct validity approach was used, employing CFA based on the original model. The results showed that the fit indices from the initial model were inadequate. Given this poor fit, we decided to modify the model using the improvement indices. As part of this process, items numbered 2, 8, 9, 13, 19, 25, 31, 32, 33, and 34 were removed because their factor loadings were below 0.4 (Table 2).

| Items | Item Content | Factor Loading | Scores (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | When you were a child, did anyone use force to take something away from you that you were carrying or wearing? | 0.358 | 0.41 ± 0.49 |

| 3 | When you were a child, did anyone break or ruin any of your things on purpose? | 0.395 | 0.56 ± 0.49 |

| 4 | Sometimes people are attacked with sticks, rocks, guns, knives, or other things that would hurt. When you were a child, did anyone hit or attack you on purpose with an object or weapon? Somewhere like: At home, at school, at a store, in a car, on the street, or anywhere else? | 0.595 | 0.37 ± 0.48 |

| 5 | When you were a child, did anyone hit or attack you without using an object or weapon? | 0.679 | 0.63 ± 0.48 |

| 6 | When you were a child, did someone start to attack you, but for some reason, it didn’t happen? For example, someone helped you or you got away? | 0.530 | 0.46 ± 0.50 |

| 7 | When you were a child, did someone threaten to hurt you when you thought they might really do it? | 0.690 | 0.61 ± 0.49 |

| 10 | Not including spanking on your bottom, when you were a child, did a grown-up in your life hit, beat, kick, or physically hurt you in any way? | 0.565 | 0.65 ± 0.48 |

| 11 | When someone is neglected, it means that the grown-ups in their life didn’t take care of them the way they should. They might not get them enough food, take them to the doctor when they are sick, or make sure they have a safe place to stay. When you were a child, were you neglected? | 0.464 | 0.54 ± 0.50 |

| 12 | When someone is neglected, it means that the grown-ups in their life didn’t take care of them the way they should. They might not get them enough food, take them to the doctor when they are sick, or make sure they have a safe place to stay. When you were a child, were you neglected? | 0.385 | 0.32 ± 0.47 |

| 14 | Sometimes groups of kids or gangs attack people. When you were a child, did a group of kids or a gang hit, jump, or attack you? | 0.468 | 0.13 ± 0.34 |

| 15 | When you were a child, did any kid, even a brother or sister, hit you? Somewhere like: At home, at school, out playing, in a store, or anywhere else? | 0.488 | 0.57 ± 0.50 |

| 16 | When you were a child, did any kids try to hurt your private parts on purpose by hitting or kicking you there? | 0.422 | 0.27 ± 0.44 |

| 17 | When you were a child, did any kids, even a brother or sister, pick on you by chasing you or grabbing you or by making you do something you didn’t want to do? | 0.444 | 0.42 ± 0.49 |

| 18 | When you were a child, did you get scared or feel really bad because kids were calling you names, saying mean things to you, or saying they didn’t want you around? | 0.502 | 0.56 ± 0.50 |

| 20 | When you were a child, did a grown-up you know touch your private parts when they shouldn’t have or make you touch their private parts? Or did a grown-up you know force you to have sex? | 0.436 | 0.31 ± 0.46 |

| 21 | When you were a child, did a grown-up you did not know touch your private parts when they shouldn’t have, make you touch their private parts or force you to have sex? | 0.525 | 0.27 ± 0.44 |

| 22 | Now think about other kids, like from school, a boyfriend or girlfriend, or even a brother or sister. When you were a child, did another child or teen make you do sexual things? | 0.708 | 0.24 ± 0.42 |

| 23 | When you were a child, did anyone try to force you to have sex; that is, sexual intercourse of any kind, even if it didn’t happen? | 0.527 | 0.26 ± 0.44 |

| 24 | When you were a child, did anyone make you look at their private parts by using force or surprise, or by “flashing” you? | 0.464 | 0.40 ± 0.49 |

| 26 | When you were a child, did you do sexual things with anyone 18 or older, even things you both wanted? | 0.385 | 0.11 ± 0.32 |

| 27 | When you were a child, did you SEE a parent get pushed, slapped, hit, punched, or beat up by another parent, or their boyfriend or girlfriend? | 0.458 | 0.49 ± 0.50 |

| 28 | When you were a child, did you SEE a parent hit, beat, kick, or physically hurt your brothers or sisters, not including a spanking on the bottom? | 0.747 | 0.52 ± 0.50 |

| 29 | When you were a child, in real life, did you SEE anyone get attacked on purpose WITH a stick, rock, gun, knife, or other thing that would hurt? Somewhere like: At home, at school, at a store, in a car, on the street, or anywhere else? | 0.749 | 0.48 ± 0.50 |

| 30 | When you were a child, in real life, did you SEE anyone get attacked or hit on purpose without using a stick, rock, gun, knife, or something that would hurt? | 0.590 | 0.63 ± 0.48 |

Next, to reduce overlap among items and incorporate the suggested improvements from the AMOS output, we allowed the covariance errors between items "10 and 12", "20 and 21", and "27 and 28" to be freely estimated. This adjustment markedly enhanced the model’s fit indices, leading to a final model that showed acceptable fit (Table 3 and Figure 1).

| Indices | X2/df | GFI | CFI | IFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended criterion | ≤ 3 | ≤ 0.9 | ≤ 0.9 | ≤ 0.9 | ≤ 0.9 | ≤ 0.08 |

| Values for the original JVQ model | 2.03 | 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.04 |

| Values for the modified JVQ model | 1.98 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: JVQ, Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire.

To evaluate the scale’s reliability, we used internal consistency methods, including Cronbach’s alpha and split-half reliability (Table 4). The total victimization score demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in both the original and revised versions, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. The subscales for sexual victimization and conventional crimes also showed acceptable reliability, with alpha coefficients of 0.70 and 0.69, respectively. However, other subscales, notably child maltreatment, exhibited lower internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values below 0.70.

| Variables, Subscales and Questionnaires | Frequency | Mean ± SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | |||

| Conventional crimes | |||

| Original JVQ | 573 | 3.26 ± 1.93 | 0.69 |

| Revised JVQ | 573 | 3.05 ± 1.84 | 0.69 |

| Child maltreatment | |||

| Original JVQ | 573 | 1.62 ± 1.14 | 0.52 |

| Revised JVQ | 573 | 1.51 ± 1.03 | 0.51 |

| Peer and sibling victimization | |||

| Original JVQ | 573 | 1.98 ± 1.39 | 0.53 |

| Revised JVQ | 573 | 1.94 ± 1.36 | 0.55 |

| Sexual victimization | |||

| Original JVQ | 573 | 1.78 ± 1.79 | 0.70 |

| Revised JVQ | 573 | 1.89 ± 1.65 | 0.71 |

| Witnessing and indirect victimization | |||

| Original JVQ | 573 | 2.21 ± 1.54 | 0.62 |

| Revised JVQ | 573 | 2.12 ± 1.40 | 0.67 |

| Total victimization score | |||

| Original JVQ | 573 | 10.84 ± 5.52 | 0.84 |

| Revised JVQ | 573 | 10.21 ± 5.17 | 0.84 |

Abbreviation: JVQ, Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire.

To examine the ability of the total victimization score and victimization scales to predict psychiatric symptoms, a simultaneous regression analysis was conducted. Before running the analysis, the key assumptions of regression were checked. Outliers were identified using the Mahalanobis distance test, which established a cutoff point of 11.3. Participants exceeding this threshold — 24 individuals — were excluded from the analysis to ensure data accuracy, leaving a final sample of 549 participants. The correlation matrix of the variables showed typical and significant correlations among all variables, confirming the assumption of linearity (Table 5). To verify the normal distribution of the data, skewness and kurtosis were assessed; since their values ranged between -2 to +2, the variables were considered normally distributed, supporting the validity of the regression analysis (Table 6).

| Variable | Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | |||||||||

| 1. Conventional crimes | 1 | 0.50 a | 0.52 a | 0.29 a | 0.39 a | 0.80 a | 0.36 a | 3.26 ± 1.93 | |

| 2. Child maltreatment | 1 | 0.45 a | 0.23 a | 0.38 a | 0.68 a | 0.38 a | 1.62 ± 1.14 | ||

| 3. Peer and sibling victimization | 1 | 0.33 a | 0.42 a | 0.76 a | 0.34 a | 1.98 ± 1.39 | |||

| 4. Sexual victimization | 1 | 0.21 a | 0.61 a | 0.55 a | 1.78 ± 1.79 | ||||

| 5. Witnessing and indirect victimization | 1 | 0.67 a | 0.31 a | 2.21 ± 1.54 | |||||

| 6. Total victimization score | 1 | 0.47 a | 10.84 ± 5.52 | ||||||

| 7. Psychiatric symptoms | 1 | 1.64 ± 0.77 |

Abbreviation: JVQ, Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire.

a P < 0.01.

| Variables and Scales | Frequency | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization | |||

| Conventional crimes | 549 | 0.01 | -0.87 |

| Child maltreatment | 549 | 0.16 | -0.87 |

| Peer and sibling victimization | 549 | 0.28 | -0.75 |

| Sexual victimization | 549 | 0.73 | -0.51 |

| Witnessing and indirect victimization | 549 | 0.23 | -0.66 |

| Total victimization score | 549 | 0.20 | -0.54 |

| Psychiatric symptoms | 549 | 0.16 | -0.52 |

As presented in Table 6, the correlations between the psychiatric symptom scores and the total victimization score — as well as all its subscales — were statistically significant, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.31 to 0.55 (P < 0.01). The results of the regression analysis predicting psychiatric symptoms based on the total victimization score and its subscales are reported in Table 7.

| Predictor Variables | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | F | P-Value | Beta | t | P-Value | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion variable | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 156.08 a | < 0.001 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Psychiatric symptoms | ||||||||||

| Constant | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14.17 | < 0.001 | - | - |

| Total victimization score | - | - | - | - | - | 0.47 | 12.49 a | > 0.001 | - | - |

| Conventional crimes | - | - | - | - | - | 0.120 | 2.50 b | 0.013 | 0.61 | 1.63 |

| Child maltreatment | - | - | - | - | - | 0.204 | 4.47 a | < 0.001 | 0.68 | 1.47 |

| Peer and sibling victimization | - | - | - | - | - | 0.094 | 1.96 | 0.051 | 0.62 | 1.62 |

| Sexual victimization | - | - | - | - | - | 0.145 | 3.58 a | > 0.001 | 0.87 | 1.15 |

| Witnessing and indirect victimization | - | - | - | - | - | 0.113 | 2.62 a | 0.009 | 0.76 | 1.32 |

a P < 0.001.

b P < 0.05.

Table 7 displays the results of a regression analysis assessing how well the total victimization score and its subscales predict psychiatric symptoms. The analysis shows that the overall victimization score explains about 22% of the variability in psychiatric symptoms (R2 = 0.22, P < 0.001), indicating that victimization experiences are significantly linked to mental health problems. The model itself is highly significant (F = 156.08, P < 0.001), suggesting that the predictor variables collectively provide meaningful information about psychiatric symptoms rather than just random association. The standardized beta coefficient of 0.47 for the total victimization score indicates a strong positive relationship: For every one-unit increase in the victimization score, psychiatric symptoms increase by approximately 0.47 units. This suggests that higher victimization levels are associated with worse mental health outcomes. Further, when examining the specific types of victimization, the results show that child maltreatment, sexual victimization, witnessing or indirect exposure to violence, and conventional crimes all significantly predict psychiatric symptoms (P < 0.05). The beta values for these subscales range from 0.11 to 0.20, indicating that each type of victimization independently contributes to psychiatric symptom severity. However, victimization by peers or siblings did not significantly predict psychiatric symptoms (P > 0.05), implying it’s lesser or no direct impact within this model. Lastly, regarding the prevalence data: Out of 573 participants, 313 (about 54.6%) scored below 12 on the victimization scale, indicating lower victimization levels, while 260 (about 45.4%) scored 12 or above, suggesting they experienced polyvictimization — exposure to multiple types of victimization.

5. Discussion

This study involved a non-random sample of 573 Iranian adults aged 18 to 45, aiming to: (1) Validate the JPQ for use in Iran; (2) examine the link between childhood polyvictimization and adult psychiatric symptoms; and (3) provide insights for targeted mental health interventions to support victims’ recovery. Initial results showed that the JVQ Screen-Sum Version (SSV: ARF) was clear and relevant. Confirmatory factor analysis indicated poor fit initially, but after removing low-loading items and allowing covariance between certain pairs, the model achieved acceptable fit, supporting its validity for assessing victimization in Iranian adults. The instrument’s cultural adaptation promotes face validity and reliability, making it useful for future research on victimization and psychiatric outcomes in Iran (22). However, further exploration of cross-cultural validity and potential response biases, such as social desirability or recall bias, is recommended. Incorporating clinical interviews or longitudinal designs could strengthen the instrument’s application.

The internal consistency of the overall victimization score was good (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) for both the original 34-item JVQ and the Persian 24-item version. Subscale reliability varied; sexual victimization and conventional crimes had acceptable alpha values (~ 0.70), but the child maltreatment subscale was lower (~ 0.51). This aligns with previous findings that victimization events tend to be independent rather than strongly correlated (4, 11, 23). The lower internal consistency likely reflects the diversity of victimization experiences, which are conceptually related but not necessarily statistically cohesive (4).

Some items were excluded due to low factor loadings, possibly reflecting cultural differences in how certain victimization experiences are perceived or reported in Iran. These exclusions may not indicate measurement problems but rather cultural discrepancies in understanding or relevance (23). The overall victimization score explained about 22% of the variance in psychiatric symptoms, with individual subscales accounting for 0.11 to 0.20 — consistent with prior research showing moderate correlations between victimization and mental health outcomes (4-6). The modest associations suggest that while victimization is a risk factor for psychiatric distress, other factors also play significant roles.

The findings underscore that polyvictimization increases the risk of psychological symptoms. Addressing these through trauma-focused therapies, resilience-building strategies, and social support could mitigate ongoing victimization and foster recovery (24-26). Since different victimization types often overlap, a comprehensive approach considering multiple trauma exposures is essential for effective intervention. Regarding methodology, all three JVQ versions produce similar results (23). We used the Screen-Sum Version for its simplicity and conservative estimate of victimization (27). However, the non-random online sampling limits generalizability, especially to populations without internet access. Self-report data may also introduce biases. Future research should incorporate larger, more diverse samples and longitudinal designs to improve validity. Additionally, peer, sibling, and lesser-studied victimization experiences warrant more attention, given their significance in shaping mental health outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, while our study makes a valuable contribution to understanding victimization, addressing some key points could significantly enhance its clarity and broader impact. Relying on instruments that measure only a limited range of victimization types can inadvertently narrow our understanding of the full scope of polyvictimization among adults, making it harder to appreciate how different forms of victimization uniquely affect individuals. The JVQ, however, offers a more comprehensive approach by providing clear definitions aligned with law enforcement and child protection classifications, thus capturing a fuller picture. Early findings from a national survey using the JVQ reveal that a significant proportion of adults have experienced victimization within the past year, many of whom report multiple incidents (14), highlighting the urgent need for more detailed and accurate data collection. This richer understanding can profoundly influence clinical interventions and social support systems, making them more targeted and empathetic. Ultimately, better data not only helps in designing more effective prevention and intervention strategies but also humanizes our approach — recognizing the complex realities faced by victims and working towards a society that offers meaningful support and hope for recovery.