1. Background

Medical training involves intense academic, emotional, and professional demands that place students at an elevated risk for mental health problems, including suicidal ideation. International meta-analyses and multi-center studies demonstrate that medical students exhibit higher rates of depression and suicidal thoughts than their non-medical peers, and that risk often increases during clinical training due to exposure to patient suffering, responsibility for clinical decisions, long hours, and performance pressure (1, 2).

Iranian data on suicidal ideation in medical students are limited, and single-site reports vary by setting and measurement approach. A few regional studies (including work from Zahedan and Tehran) document substantial psychiatric morbidity and highlight gaps in accessible counseling and stigma reduction in university settings.

2. Objectives

The scarcity of systematic national surveillance of suicidality among medical students in Iran motivates site-level studies such as this one (3-7): By comparing basic-science and clinical phases, we aim to identify educational stages with the highest need for intervention and to inform locally appropriate support strategies.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study uses data collected from medical students enrolled at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (ZUMS) during 2023. The target population comprised students in basic sciences (pre-clinical years) and clinical training (internship/clinical years). Inclusion criteria included currently enrolled medical students who provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria involved self-reported current treatment for a severe psychiatric disorder that would preclude accurate completion of the questionnaire.

3.2. Sampling

A stratified random sampling approach was used to ensure representation across educational levels and sex. Enrollment lists were obtained from the university; random selection within strata produced the analytic sample of 204 students (105 basic-science and 99 clinical interns).

3.3. Sample Size

A priori sample-size planning aimed to detect at least a medium effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.5) between the two educational groups, with 80% power at α = 0.05 (two-sided), which requires approximately 64 participants per group. Our final sample (105 vs. 99) provided adequate power to detect medium and smaller effects (≈ 0.4) and to permit subgroup comparisons (sex, residence, GPA) with caution.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation

The 19-item Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI, Persian version) assessed current suicidal thoughts and intent over the past week. The Persian translation demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in pilot testing with medical students (Cronbach’s α = 0.89 in the present sample). Higher scores indicate greater intensity of suicidal ideation. Age, sex, marital status, residence (dormitory/with parents/private house), and academic performance (GPA on a 20-point scale) were collected. Questionnaire completeness was reviewed before analysis. Participants with missing BSSI total scores were excluded from analyses (listwise deletion). For demographic items with rare missingness, analyses used available-case methods.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and group comparisons were performed using chi-square and t-tests, with significance set at P < 0.05. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were calculated for the main comparison, and all analyses were conducted in SPSS v22.

4. Results

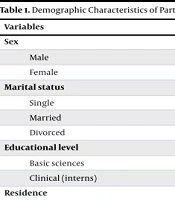

The study sample consisted of 204 students with a mean age of 22.7 ± 3.6 years (range: 18 - 42). Of these, 118 (57.8%) were male and 86 (42.2%) were female. Most participants were single (n = 153, 75%). By educational level, 105 (51.5%) were basic-science students and 99 (48.5%) were clinical interns. In terms of residence, 82 (40.2%) lived in dormitories, 91 (44.6%) with parents, and 31 (15.2%) in private houses. The mean GPA was 16.13 ± 1.22 (on a 20-point scale) (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 118 (57.8) |

| Female | 86 (42.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 153 (75.0) |

| Married | 38 (18.6) |

| Divorced | 13 (6.4) |

| Educational level | |

| Basic sciences | 105 (51.5) |

| Clinical (interns) | 99 (48.5) |

| Residence | |

| Dormitory | 82 (40.2) |

| With parents | 91 (44.6) |

| Private house | 31 (15.2) |

| Suicidal thoughts | |

| No | 126 (61.8) |

| Yes | 71 (34.8) |

| Preparation for suicide | 7 (3.4) |

Clinical interns reported significantly higher mean BSSI scores compared to basic-science students (7.32 ± 7.39 vs. 4.39 ± 6.24; t(202) = 2.98, P = 0.003). The pooled-SD effect size (Cohen’s d) was 0.43, indicating a small-to-moderate effect. By sex, male students showed mean scores of 3.73 ± 5.83 (basic) vs. 6.04 ± 7.15 (clinical), a non-significant difference (P = 0.064). Female students, however, demonstrated a significant difference: 5.07 ± 6.62 (basic) vs. 9.75 ± 7.35 (clinical, P = 0.004). Married clinical interns scored markedly higher (6.77 ± 6.03) than married basic-science students (0.33 ± 0.51, P < 0.001).

Residence was also associated with suicidal ideation: Interns living in dormitories reported higher scores (10.71 ± 8.17) than their basic-science counterparts (6.39 ± 7.06, P = 0.024). Students living with parents showed lower scores compared to those in dormitories or private housing. Academic performance was another significant factor. Interns with GPA < 16 had higher BSSI scores (11.16 ± 7.57) compared with basic-science students in the same GPA category (4.08 ± 5.59, P = 0.001). No significant GPA-linked difference was observed within the basic-science group (Table 2).

| Variables | Basic | Clinical | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | |||

| < 22 | 4.22 ± 6.12 | 6.00 ± 0.12 | 0.76 |

| ≥ 22 | 8.25 ± 7.29 | 8.95 ± 7.46 | 0.802 |

| Total | 4.39 ± 6.24 (n = 105) | 7.32 ± 7.39 (n = 99) | 0.003 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3.73 ± 5.83 | 6.04 ± 7.15 | 0.064 |

| Female | 5.07 ± 6.62 | 9.75 ± 7.35 | 0.004 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 4.45 ± 6.59 | 5.80 ± 7.03 | 0.23 |

| Married | 0.33 ± 0.51 | 6.77 ± 6.03 | < 0.001 |

| Divorced | 16.03 ± 0.21 | 16.90 ± 6.36 | 0.851 |

| Residence | |||

| Dormitory | 6.39 ± 7.06 | 10.71 ± 8.17 | 0.024 |

| With parents | 2.40 ± 4.20 | 5.46 ± 5.94 | 0.006 |

| Private house | 0.18 ± 0.40 | 8.60 ± 8.70 | 0.001 |

| GPA | |||

| < 16 | 4.08 ± 5.59 | 11.16 ± 7.57 | 0.001 |

| ≥ 16 | 4.49 ± 6.46 | 5.49 ± 6.61 | 0.367 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Two independent sample t-test, GPA on a 20-point scale.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrated that clinical-phase medical students at ZUMS reported significantly higher suicidal ideation scores compared to their basic-science peers, with a small-moderate effect size. This finding aligns with international literature indicating that psychological strain intensifies during clinical training due to clinical responsibilities, exposure to patient suffering, and heightened performance pressures (2, 8). Female clinical students exhibited significantly higher suicidal ideation than female basic-science students. This pattern is consistent with previous studies that report greater internalizing symptoms and higher rates of suicidality among female medical students. Potential explanations include gendered role expectations, emotional labor during patient care, and disparities in access to support resources (9).

Married clinical interns and students residing in dormitories reported elevated suicidal ideation. Married students may experience compounded academic and familial responsibilities, while dormitory life may be associated with reduced social support or increased isolation. These contextual stressors highlight the importance of institutional interventions such as peer-support programs, family-friendly scheduling, and expanded access to counseling (10). Interns with lower GPAs were more vulnerable to suicidal ideation, suggesting that academic difficulties during clinical training can intensify stress and feelings of inadequacy. This finding underscores the need for supportive academic programs, including remediation and mentorship that are sensitive to students’ mental health needs (11).

This study has several limitations, including its cross-sectional design, single-university sample, reliance on self-report measures, incomplete subgroup data, and small subgroup sizes, which limit generalizability and reproducibility. Nonetheless, the findings offer important implications, underscoring the need to integrate mental health education into the curriculum, establish routine screening during clinical transitions, and expand access to counseling. Targeted interventions such as stress-management workshops, mentorship, and workload adjustments should also be piloted and systematically evaluated.

Our findings highlight the vital role of integrating mental health education into medical training and ensuring that students have access to appropriate mental health services, steps that could significantly reduce associated risks. These results carry important implications for the medical field: There is an urgent need to rethink and adapt both educational and clinical approaches to better support the psychological well-being of future healthcare professionals.

Future research should focus on designing, implementing, and evaluating targeted interventions that reduce stress and improve mental health outcomes among medical students, with particular attention to inclusivity and equitable access for students from diverse backgrounds. Our findings suggest a higher prevalence than some studies but are also reflective of the mental health challenges that medical students face globally.