1. Background

Suicidal ideation (SI) encompasses the spectrum of thoughts, ideas, and tendencies related to wishing to end one’s life. SI has emerged as a significant precursor and contributor to suicide attempts, particularly among adolescents (1-3). The SI often signals the initial phase of a trajectory leading toward a suicide attempt (4). Globally, suicide ranks as the second most common cause of death for individuals aged 15 to 29. However, due to the pervasive stigma surrounding suicide in many societies, the actual prevalence of reported cases is likely to be significantly underestimated (5).

According to a suicide report by the World Health Organization (WHO), the suicide rates in Iran for the year 1391 (approximately 2012 - 2013) among young individuals aged 15 to 29 were reported as 7.8 per 100,000, comprising 10.0 for males and 5.5 for females (5). The estimated overall prevalence of SI in the general population ranges between 10.24% and 26.72% (6). Specifically, within the Iranian context, localized studies among high school adolescents indicate an approximate SI prevalence rate of 4.1% (7).

To effectively contextualize the complex interplay between childhood trauma, sleep quality, loneliness, and the development of SI, theoretical grounding is necessary. The current study draws upon O’Connor’s Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior (8) as the guiding framework. This model posits that suicidal desire arises from a combination of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, which, when coupled with the acquired capability for suicide, increases the risk of an attempt (8). In the context of this research, childhood trauma is conceptualized as a significant source of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, while poor sleep quality may act as a physiological pathway contributing to the acquired capability for suicide.

Suicide is a multifactorial phenomenon shaped by an interplay of neurobiological, psychological, and social risk factors (9-11). Several theoretical perspectives have been proposed to explain how childhood adversity may elevate suicide risk. The stress‑sensitization hypothesis suggests that early‑life trauma sensitizes individuals to later stressors, making them more vulnerable to emotional dysregulation and psychiatric disorders in adulthood compared to those without such histories (12). Similarly, the stress‑diathesis model of suicidal behavior posits that certain enduring vulnerabilities—often related to disturbances in neural circuitry and neurotransmitter dysregulation—interact with external stress to precipitate suicidal crises (13). Complementing these models, the Interpersonal‑Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior (8, 14) emphasizes that SI emerges when individuals simultaneously experience perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, together with an acquired capability for suicide (15). Childhood maltreatment—such as harsh punishment, verbal or sexual abuse, and emotionally invalidating parenting—can erode a sense of belonging and generate maladaptive interpersonal schemas, thereby amplifying vulnerability to SI during adolescence (16). Empirical studies have consistently shown that adolescents exposed to childhood trauma display higher levels of SI and attempts compared with their non‑traumatized peers (17).

Sleep quality represents another critical yet under‑explored factor linking trauma to suicidality. Sleep plays an essential role in neural maturation and emotional regulation during adolescence; circadian shifts and early school schedules often exacerbate chronic sleep deprivation in this age group (18, 19). In a recent study, it was found that there is a strong connection between poor sleep quality and acceptance in the psychiatric care sector for both white and black participants (20). A recent study found a significant and positive link between feelings of loneliness and thoughts of suicide (21). A study found that loneliness was strongly linked to thoughts of suicide, whereas factors like living alone, staying home, and the number of days spent social distancing didn’t show the same connection (22). In a separate investigation, findings indicated that loneliness was not a significant predictor of suicidal thoughts over time or in cross-sectional analyses when taking depressive symptoms into account (23). Studies reveal that adolescents with poor sleep are up to 13 times more likely to report SI than those with adequate rest (17, 24). Moreover, recent meta‑analytic evidence indicates a reciprocal relationship between loneliness and sleep problems, whereby loneliness predicts nightmares and overall sleep disturbance (25).

Despite this accumulating evidence, few studies have simultaneously examined how both sleep quality and feelings of loneliness may jointly mediate the association between childhood trauma and SI among adolescents. Addressing this gap, the present study aims to investigate whether these two factors serve as psychological and physiological pathways connecting early traumatic experiences to SI in youth.

Given the profound and wide‑ranging consequences of suicide for individuals, families, and society, early identification of psychological risk markers is essential for effective prevention. The SI often represents the earliest and most modifiable stage in the trajectory toward suicidal behavior, underscoring the need for research focused on its antecedents during adolescence—a developmental period marked by heightened emotional sensitivity and vulnerability to stress. Building upon prior evidence linking childhood trauma with poor sleep and elevated loneliness, the present study seeks to clarify whether sleep quality and feelings of loneliness act as mediating mechanisms through which early traumatic experiences contribute to suicidal thoughts among teenagers. By addressing this mediation pathway, the study aims to enhance the conceptual understanding of suicide risk and to inform targeted prevention and intervention strategies for youth mental health.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to examine the association between childhood trauma and SI in adolescents while investigating the mediating roles of sleep quality and loneliness. By identifying how these psychological factors contribute to the pathway from early adversity to suicidal thoughts, this research seeks to provide insights that can inform targeted prevention strategies and interventions to enhance adolescent mental well‑being.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2024 and included 540 school students (n = 540) aged between 12 and 18 years. Participants were recruited via convenience sampling from local secondary schools within Tehran.

The study’s final sample size was determined a priori using G*Power software (26). Based on an anticipated small effect size (f 2 = 0.02), a statistical power of 0.80, and an alpha level of 0.05 for a regression analysis with three predictor variables, the required sample size was calculated to be 540 individuals.

Prior to data collection, informed consent was obtained from the parents/guardians, and assent was secured from the adolescent participants themselves. The entire protocol received approval from the Student Research Committee in the Department and Faculty of Clinical Psychology at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3.2. Measurements

The SI was assessed using the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI). This 19-item self-report instrument is designed to assess the intensity of suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and plans experienced over the preceding week. Responses are recorded on a 3-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (no SI) to 2 (active ideation with intent or plan). The total score is calculated by summing the individual item scores, yielding a possible range of 0 to 38. The scale includes 5 initial screening questions to determine the presence of active or passive suicidal tendencies; participants endorsing suicidal thoughts proceed to complete the remaining 14 items.

The BSSI demonstrates high internal consistency, with original reliability estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) ranging from 0.87 to 0.97 (27). In the Iranian context, Esfahani et al. reported a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.80 for the Persian adaptation (28).

Childhood trauma experiences were measured using the Bernstein Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ). This 28-item instrument assesses exposure to various forms of maltreatment, categorized into five dimensions: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Participants rate the frequency of each experience using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

The internal consistency of the CTQ has been well-established. For instance, among an adolescent sample, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were reported as: 0.87 for emotional abuse, 0.86 for physical abuse, 0.95 for sexual abuse, 0.89 for emotional neglect, and 0.78 for physical neglect (29). In a validation study conducted in Iran, Ebrahimi et al. reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the five dimensions ranging between 0.81 and 0.98 (30).

Sleep quality and disturbances were assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), an 18-item self-report questionnaire developed by Buysse et al. (31) to evaluate overall sleep quality over the preceding month. The instrument comprises seven component scores: Subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction. The initial four questions are open-ended (e.g., “How many hours of actual sleep do you get at night?”), while subsequent items assess the frequency or severity of sleep issues using a four-point Likert scale: 0 (no issues in the past month), 1 (less than once a week), 2 (once or twice a week), and 3 (three or more times a week). Component scores range from 0 to 3, and the overall PSQI score ranges from 0 to 21, with a score of 5 or higher indicating clinically significant sleep disturbances. The internal consistency reported by the developers was a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81 (31). Furthermore, in Iranian studies, Kakouei et al. reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 (32), and Chehri et al. also found good reliability in an adolescent population (33).

Loneliness was assessed using the UCLA Loneliness Scale, developed by Russell et al.(34). This 20-item self-report instrument utilizes a four-point response format: 1 (“never”), 2 (“rarely”), 3 (“sometimes”), and 4 (“always”). The scale is balanced, containing 10 negatively phrased items and 10 positively phrased items. Scoring for items 1, 5, 6, 9, 10, 15, 16, 19, and 20 is reversed, whereby “never” receives a score of 4 and “always” receives a score of 1. Total scores range from a minimum of 20 to a maximum of 80, with an approximate average score of 50; a score above the average suggests a higher perceived level of loneliness. The revised version of the scale demonstrated a reliability of 78%. Furthermore, the test-retest reliability reported by Russell, Peplau, and Ferguson was 89% (34). In an Iranian context, Hasani established a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 for this scale, indicating strong internal consistency, and also reported good convergent and discriminant validity (35).

3.3. Procedure

This study protocol received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran (IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1403.271). All procedures adhered strictly to the ethical standards for research involving human participants.

Participants and Consent: The study targeted adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. Prior to participation, informed written consent was obtained from the parents/legal guardians, and assent was separately secured from the participating adolescents themselves.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Inclusion in the study required participants to meet a minimum threshold on the assessment of SI. Specifically, participants were required to obtain a minimum score of 4 on the Self-Rating BSSI. Conversely, participants were excluded if they provided incomplete questionnaires, exhibited patterns indicative of biased responding (e.g., straight-lining or random responding identified during data cleaning), or scored between 0 and 3 on the BSSI, suggesting a low-risk profile for suicidal thoughts.

Following selection based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, participants were referred to a clinical psychologist affiliated with the research team. The psychologist thoroughly explained the study’s objectives, methodology, and the sensitive nature of the questionnaires, ensuring both the adolescents and their guardians fully understood and consented to their involvement.

Participants were then instructed to complete the battery of self-report measures privately and individually. The order of administration included: The Bernstein CTQ, the PSQI, and the Russell Loneliness Scale (UCLA).

Addressing Response Bias: Given the sensitive nature of questions regarding SI and childhood trauma, there was a recognized potential for self-report bias, particularly social desirability bias. To mitigate this, strict protocols for anonymity and confidentiality were implemented. Participants were explicitly informed that their responses would be coded (not linked to personal identifiers) and were asked to complete all questionnaires privately, without external influence. Throughout the entire process, the rights and privacy of all individuals were prioritized, including ensuring written consent was obtained from all parties and confirming the right to withdraw from the study at any point without penalty.

3.4. Data Analysis

The collected data were initially imported from Microsoft Excel into the R environment for preliminary analysis, specifically to assess the distribution of variables. Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Observing significant departures from normality across key variables (P < 0.05), the analysis strategy was adjusted. For subsequent Structural Equation Modeling Modeling (SEM) using the lavaan package, the Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimator was employed to ensure the validity and reliability of model estimation despite the non-normal data distribution.

Descriptive statistics, including measures for demographic factors such as age and gender, were performed. Further inferential and relational analyses, including chi-square tests, correlation coefficients, and path analysis models, were conducted using SPSS Version 24. All statistical tests were evaluated for significance using an alpha level of P < 0.05.

4. Results

A total of 540 participants aged between 12 and 18 years (M = 17.3, SD = 1.32) took part in the study, including 414 boys (81.5%) and 94 girls (18.5%). No significant differences were observed between male and female participants in the main study variables (P > 0.05), and therefore, analyses were conducted on the total sample. Detailed statistics including skewness, kurtosis, mean, and standard deviation for various metrics such as childhood trauma, suicidal thoughts, feelings of loneliness, and sleep quality are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | 50.66 ± 4.19 | -0.004 | 7.47 |

| Childhood trauma | 63.03 ± 8.27 | -1.85 | 7.07 |

| Sleep quality | 12.77 ± 4.37 | 0.66 | -1.05 |

| Suicide ideation | 14.21 ± 8.33 | -0.27 | -0.27 |

Before conducting the path analysis, all underlying assumptions were examined. Univariate normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and due to significant deviations (P < 0.05), the MLR estimator was applied. Linearity between variables was confirmed via visual inspection of scatterplots. Multicollinearity was assessed using Variance Inflation Factor (VIF < 3) and tolerance (> 0.30), showing no multicollinearity concerns. The Durbin-Watson statistic (1.98) supported the independence of residuals. Multivariate normality was evaluated using Mardia’s coefficient, indicating mild non-normality, which further justified the use of the MLR estimator. Outliers were examined using Mahalanobis distance, and two multivariate outliers were excluded prior to analysis.

Table 2 presents the correlation matrix of the variables, revealing a notable negative correlation between childhood trauma and sleep quality, with a coefficient of R = -0.34.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide ideation | 1 | - | - | - |

| Childhood trauma | 0.29 | 1 | - | - |

| Feelings of loneliness | 0.11 | 0.241 | - | - |

| Sleep quality | -0.31 | -0.34 | -0.05 | 1 |

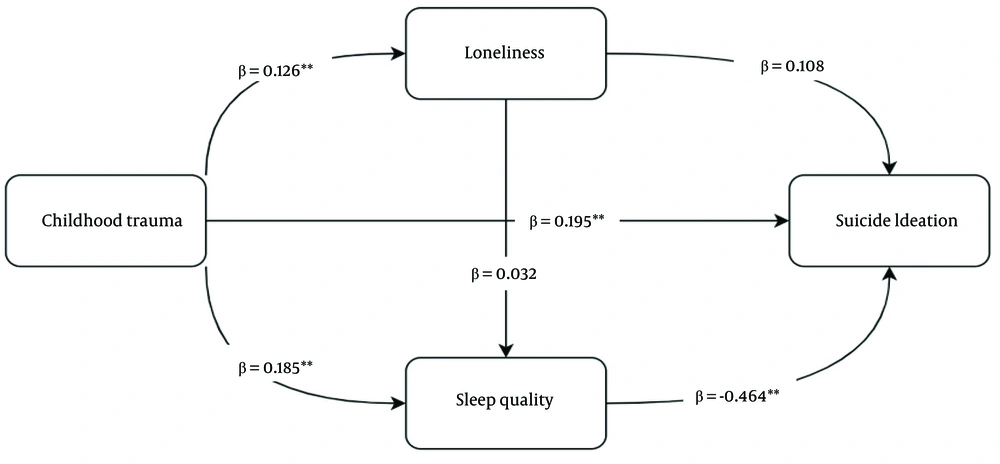

Table 3 illustrates that the proposed model demonstrates a reasonably good fit. In Figure 1, we can see the direct impact of childhood trauma on suicide ideation (β = 0.195), feelings of loneliness (β = 0.126), and sleep quality (β = 0.185). Additionally, the direct influence of feelings of loneliness (β = 0.108) and sleep quality (β = -0.464) on suicide ideation is also highlighted.

| Indices | χ² | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores | 0.52 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.000 | 0.01 |

Abbreviation: CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

The path analysis model was utilized to explore how childhood trauma impacts suicide ideation, looking specifically at loneliness and sleep quality as mediators. The results indicated an excellent fit to the data, as evidenced by the fit indices: Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 1.000), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI = 1.000), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.000), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.000). These figures suggest that the model accurately captures the relationships among the variables and adheres to the underlying theoretical framework.

As presented in Table 4, the indirect effects of childhood trauma on suicide ideation were examined across different pathways. The indirect effect mediated through loneliness was not statistically significant (β = 0.014, SE = 0.011, Z = 1.20, P = 0.231), suggesting that loneliness alone does not serve as a meaningful mediator in the relationship between childhood trauma and suicide ideation. In contrast, the indirect effect mediated through sleep quality was significant and substantial (β = 0.086, SE = 0.020, Z = 4.29, P < 0.001), indicating that sleep quality plays a critical role in linking childhood trauma to suicide ideation. The combined pathway involving both loneliness and sleep quality was not significant (β = -0.002, SE = 0.003, Z = -0.69, P = 0.493), suggesting that the dual mediation pathway is not supported by the data.

| Path | Estimate | St. Error | Z-Value | P-Value | Std. All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood trauma > loneliness > suicide ideation | 0.014 | 0.011 | 1.197 | 0.231 | 0.014 |

| Childhood trauma > sleep quality > suicide ideation | 0.086 | 0.02 | 4.287 | 0.001 | 0.085 |

| Childhood trauma > loneliness > sleep quality > suicide ideation | -0.002 | 0.003 | -0.686 | 0.493 | -0.002 |

As indicated in Figure 1, the total effect of childhood trauma on suicide ideation was significant (β = 0.293, SE = 0.038, Z = 7.71, P < 0.001), reflecting both direct and indirect effects. This underscores the critical influence of childhood trauma and sleep quality on suicide ideation, while the impact of loneliness appears to be less pronounced. The model explained a considerable portion of the variance in suicide ideation (R² = 0.316), indicating that the factors and mediators included accounted for 31.6% of the outcome's variability.

Regarding the mediating variable of sleep quality, the variance explained was moderate (R² = 0.122), indicating that childhood trauma significantly is associated with sleep quality. In contrast, the variance explained for loneliness was modest (R² = 0.062), suggesting that childhood trauma does not strongly relate to this variable. These findings highlight the significant association between sleep quality and SI, while the observed relationship of loneliness to this outcome was relatively minor.

5. Discussion

The findings indicate a strong positive correlation between childhood trauma and suicidal thoughts, with an R² value of 0.316. Importantly, the results suggest that sleep quality serves as a key mediator in this connection. On the other hand, the sense of loneliness did not appear to directly mediate this relationship. Numerous studies have highlighted a significant link between feelings of loneliness and the quality of sleep (16); it can be inferred that while loneliness may not directly mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and suicidal thoughts, it does align with earlier research findings by negatively impacting sleep quality (15, 16). Feelings of loneliness are significantly associated with an increase in thoughts of self-harm. Research shows that loneliness negatively impacts overall sleep quality. This connection is even stronger for those who have experienced violence or maltreatment during their adolescence or childhood (36).

Consistent with earlier research, people who have faced trauma in their childhood often show signs of apathy and non-emotional behaviors. This can contribute to feelings of isolation and may increase the risk of suicidal thoughts in those affected (37). Adolescents who faced psychological abuse and neglect during their childhood are at a higher risk of experiencing depressive moods. These feelings of depression are strongly correlated with difficulties with sleep. Moreover, having sleep problems on their own can also heighten thoughts of suicide among these young individuals (38). Childhood trauma often results in emotional detachment, which can heighten feelings of loneliness (34, 35, 37). Childhood trauma shows a significant association with symptoms of depression, and this relationship appears to be partially accounted for by feelings of loneliness (39).

Sleep quality is linked to childhood trauma in a notable way. Research on maltreatment and its effects on adolescents shows that those who experience more severe maltreatment in childhood tend to face greater sleep disturbances during their teenage years. It appears that psychological stress plays a role in this connection. A history of childhood maltreatment was strongly associated with the presence of sleep issues in adolescence (33, 40).

This research found a meaningful negative connection between suicidal thoughts and the quality of sleep, aligning with earlier studies (38). Sleep issues and suicidal thoughts can be interconnected through three key psychological factors: Negative thinking patterns, social isolation combined with feelings of detachment, and the ways we manage our emotions. Additionally, the quality of sleep was found to be a relevant factor in the association between pre-sleep feelings of entrapment and levels of SI upon waking (38).

This cross-sectional research investigates a significant mental health concern in adolescents: The connection between adverse childhood experiences (traumas) and SI. The results indicate a substantial and positive correlation between these two important factors. This implies that an increase in traumatic experiences in early childhood is associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing suicidal thoughts during adolescence.

The key and enlightening aspect of this research is to explore how loneliness and sleep quality act as mediators in this connection. In other terms, the findings indicate that childhood trauma is not directly associated with suicidal thoughts; instead, this relationship is frequently characterized by the presence of profound loneliness and impaired sleep quality as mediators.

Childhood trauma can be compared to a harsh seed that gets buried in the youthful mind and spirit. This painful seed may have origins such as feelings of isolation and disturbances in sleep. When a teenager deals with the effects of trauma, they might feel alienated, alone, and misunderstood, which further intensifies their sense of isolation. Additionally, the psychological strain from unresolved trauma shows a strong correlation with specific sleep pattern disturbances, including insomnia, nightmares, or a decline in overall sleep quality.

Isolation and inadequate sleep quality show a significant association with increased susceptibility for adolescents to experience SI. Intense loneliness is strongly correlated with feelings of frustration and worthlessness, whereas poor sleep is observed concurrently with impaired cognitive functions, emotional control, and psychological strength, coinciding with the emergence of distressing and hopeless thoughts.

Ultimately, the research highlights the critical need for prompt recognition and action for teenagers who have experienced childhood trauma, and it also proposes that prevention and treatment initiatives for SI should incorporate methods aimed at alleviating feelings of isolation and enhancing sleep quality for this at-risk population. This understanding opens up avenues for more impactful and holistic strategies to bolster adolescent mental health and mitigate suicide risks.

Based on the findings from this and related studies, childhood trauma demonstrates a significant correlation with both sleep pattern disturbances and feelings of depression. Furthermore, these factors are frequently observed concurrently with the escalation to suicidal thoughts over time. It’s crucial to recognize the importance of addressing childhood trauma and implementing effective psychological interventions.

The clinical applications of this research are significant and direct. Primarily, the findings advocate for the integration of routine childhood trauma screening into standard clinical assessments for adolescents presenting with sleep disorders. This enables early identification and paves the way for trauma-informed interventions, such as Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), which address the root cause of hyperarousal rather than merely managing the symptom of insomnia. Furthermore, this evidence underscores the necessity for collaborative care models where mental health professionals, sleep specialists, and pediatricians work together to develop holistic treatment plans. Ultimately, by recognizing sleep disturbances as a core biomarker of trauma, this research informs better prevention strategies, destigmatizes sleep problems, and guides the development of targeted therapies to improve long-term mental and physical health outcomes for affected adolescents.

This study has several important limitations that warrant consideration in interpreting the results. Firstly, the cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inferences; establishing the temporal precedence between trauma, sleep disruption, and SI requires future longitudinal research. Secondly, while our mediation analysis provided insight, the model structure may not fully capture the complex, bidirectional relationship between loneliness and sleep quality; future studies employing SEM or the 3ST framework could better differentiate the independent and interactive effects of these mediators. Thirdly, the findings were derived from a non-clinical sample of healthy adolescents, which may limit the direct generalizability of the magnitude of these associations to clinical populations already receiving treatment for SI or severe depressive disorders. Consequently, the current findings should be interpreted primarily as strong correlations rather than definitive causal pathways, especially regarding the relative contributions of loneliness versus sleep architecture.

Given the cross-sectional design, causal inferences cannot be made and the findings should be interpreted as correlational rather than causal. Given the sensitive nature of the questions on SI and childhood trauma, self-report bias (particularly social desirability bias) may have influenced responses. To minimize this, anonymity and confidentiality were emphasized and questionnaires were completed privately.

5.1. Conclusions

In general, based on the results of this and similar studies, childhood trauma is strongly associated with sleep disturbances and depressed moods. Consequently, these findings underscore the relevance of addressing childhood trauma through targeted psychological interventions.