1. Background

Inherited plasma coagulopathy includes a spectrum of coagulation factor deficiencies, specifically X-linked factor (F) VIII or FIX deficiencies, which are known as hemophilia A or B, respectively. In addition, other rare hemophilia diseases are hereditary bleeding disorders that result in deficiencies of fibrinogen (FI), prothrombin (FII), intrinsic pathway factors (XII, XI, and IX), extrinsic pathway factor (FVII), FXIII, and combined factors deficiency (1-3). Patients with hemophilia (PWH) tend to bleed in the skin, muscles, joints, mouth, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), etc. (4).

Today, the life expectancy of hemophilia patients is equivalent to that of healthy people. Furthermore, acute bleeding episodes are managed appropriately, and while bleeding cannot be completely avoided, it is less likely to lead to death (5). Therefore, recurrent spontaneous or trauma-related bleeding in muscles or joints is common and can potentially lead to painful and irreversible arthropathies (6, 7). The nature of joint pain can be acute — due to bleeding — or chronic — due to repeated bleeding leading to angiogenesis in the synovium and pannus formation that cause joint degeneration, arthritis, synovitis, and pain (8, 9). More than half of PWH adults have chronic pain that causes disability and reduced quality of life (QoL), and approximately 89% of them have experienced at least one pain exacerbation in a month (10). Although pain episodes are common, care and knowledge about pain management are inadequate (11). However, pharmacologic recommendations for pain in PWH include acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), and opioids (12).

The alcohol, smoking, and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) is a substance abuse disorder assessment tool that was first developed by an international group of substance abuse researchers for the World Health Organization (WHO) to detect psychoactive substance use and related problems in primary care patients. The questionnaire was initially prepared in English and then translated into many languages. It consists of a series of questions that inquire about the frequency and quantity of substance use in the past 3 months (13-15). Increased prescription of opioids for pain relief in PWH may lead to dependence. In addition, the illness-related challenges and reduced QoL can damage social personality and cause mental disorders and substance abuse (16, 17).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of substance abuse in PWH and its related factors.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This is a descriptive-analytical, cross-sectional study performed on PWH above 12 years old, who required blood products and follow-up visits and were referred to Ali-Asghar Pediatric Hospital in Zahedan, Iran, in 2024. This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was ethically approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (approval ID: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1403.238). Informed consent was obtained from the patients or their legal guardians.

3.2. Data Collection

First, patients’ information such as date of birth, gender, education level, family history of substance abuse, surgical history, and use of alcohol, cigarettes, and other drugs was obtained through a self-reported questionnaire. The number of involved joints and types of factor deficiencies were evaluated by a hematologist. Then, an accurate history of pain and substance abuse disorders was obtained based on the Pain Assessment Questionnaire and Dependency Screening Test Questionnaire. The Pain Intensity Questionnaire was based on the patient's response to the Pain Assessment Questionnaire, ranging from 0 - 10, known as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (18). The ASSIST was used for the assessment of substance abuse status. The ASSIST scores are classified into low risk (≤ 3), moderate risk (4 - 26), and high risk (≥ 27). The average reliability test coefficients for the Persian-ASSIST Questionnaire ranged from Cronbach’s α of 0.79 - 0.95, indicating excellent reliability (13-15).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to analyze the demographic characteristics of the study. The distributions of quantitative data were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, with parametric and nonparametric statistics then applied as appropriate. Continuous (≥ 2 variables) and categorical variables were compared using the t-test, ANOVA, and chi-Square test, respectively. Confidence intervals were computed at a P-value of 0.05. The analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA).

4. Results

In this study, 80 patients with PWH were examined for substance abuse disorders. Among them, 22 participants (27.5%) were aged 12 - 20 years, and 58 participants (72.5%) were older than 20. There were 24 female participants (30%) and 56 male participants (70%). The distribution of factor deficiency is as follows: FVIIID (35 patients, 43.8%), FXIIID (31 patients, 38.7%), FIXD (10 patients, 12.5%), and FID (4 patients, 5%).

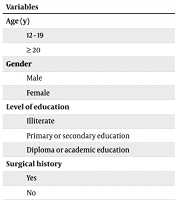

Of the 80 patients in the sample, 28 patients (35%) had substance abuse disorders, with 22 (78.6%) reporting pain. Additionally, the mean ± SD pain intensity in the PWH (regardless of substance use) was 8.21 ± 2.12; it was 8.53 ± 1.71 in PWH with substance abuse disorder and 7.77 ± 2.54 in PWH without substance abuse disorder. The frequency of pain in the substance abuse disorder group was significantly higher than in the other group (P < 0.001). Furthermore, male gender, age of 20 years and older, lower education levels, and a family history of substance abuse were associated with a higher risk of substance abuse disorder (P < 0.05); while there were no significant differences between the two groups based on surgical history (P = 0.167). Clinically, PWH patients with FVIIID and FIXD, in particular, had more than 3 joint involvements and were more significantly associated with substance abuse disorder (P < 0.001, Table 1).

| Variables | With Substance Abuse (N = 28) | Without Substance Abuse (N = 52) | Total (N = 80) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | < 0.001 | |||

| 12 - 19 | 0 (0) | 22 (42.3) | 22 (27.5) | |

| ≥ 20 | 28 (100) | 30 (57.7) | 58 (72.5) | |

| Gender | 0.001 | |||

| Male | 26 (92.9) | 30 (57.7) | 56 (70) | |

| Female | 2 (7.1) | 22 (42.3) | 24 (30) | |

| Level of education | 0.01 | |||

| Illiterate | 13 (46.4) | 8 (15.4) | 21 (26.2) | |

| Primary or secondary education | 9 (32.1) | 29 (55.8) | 38 (47.6) | |

| Diploma or academic education | 6 (21.4) | 18 (28.8) | 21 (26.2) | |

| Surgical history | 0.167 | |||

| Yes | 16 (57.1) | 21 (40.4) | 37 (46.2) | |

| No | 12 (42.9) | 31 (59.6) | 43 (53.8) | |

| Type of factor deficiency | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 0 (0) | 4 (7.7) | 4 (5) | |

| 8 | 18 (64.3) | 17 (32.7) | 35 (43.8) | |

| 9 | 6 (21.4) | 4 (7.7) | 10 (12.5) | |

| 13 | 4 (14.3) | 27 (51.9) | 31 (38.7) | |

| Number of involved joints | < 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 1 (3.6) | 28 (53.8) | 29 (36.2) | |

| > 3 | 10 (35.7) | 15 (28.8) | 25 (31.2) | |

| 3 - 6 | 10 (35.7) | 6 (11.5) | 16 (20) | |

| > 6 | 7 (25) | 3 (5.8) | 10 (12.5) | |

| Familial history of substance abuse | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 23 (82.1) | 14 (26.9) | 37 (46.2) | |

| No | 5 (17.9) | 38 (73.1) | 43 (53.8) | |

| Pain | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 22 (78.6) | 17 (32.7) | 39 (48.8) | |

| No | 6 (21.4) | 35 (67.3) | 41 (51.2) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

The analysis of the ASSIST Questionnaire results showed that the frequency of greater than moderate risk degree of dependence in PWH with tobacco and opium abusers was 85.7% and 95.5%, respectively. However, the rates of PWH abusing alcohol and cigarettes with a low-risk dependence degree were 80% and 100%, respectively (Table 2).

| Degree of Dependence | Type of Substance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco (N = 7) | Alcohol (N = 5) | Opium (N = 22) | Cigarettes (N = 1) | |

| 0 - 3 | 1 (14.3) | 4 (80) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (100) |

| ≥ 4 | 6 (85.7) | 1 (20) | 21 (95.5) | 0 (0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

In this single-center cohort of PWH, the prevalence of substance use disorders (SUD) and high-risk substance behaviors was 35% overall and was higher among adults, individuals with chronic arthropathy and pain, and those with prior opioid exposure. Alcohol and opioids were the most commonly implicated substances, followed by stimulants and cannabis. Pain is considered one of the most important aspects of the disease’s symptoms, which interferes with the daily routines of PWH (19, 20). Many PWH suffer acute pain during bleeding episodes and chronic pain from long-term hemarthrosis and joint deterioration (21). The method of coping with and treating this pain depends on the patient’s individual personality, social environment, and severity of the symptoms (22, 23). Currently, many choices (such as opioids or NSAIDs, etc.) are available for pain relief; however, abuse of these drugs can reduce life expectancy and QoL (24, 25). Therefore, knowing the drug dependence status of PWH may lead us to enhance their QoL, physical activities, and sleep quality.

There are not many publications that address substance addictions in hemophilia patients or classify the type of substance or the reasoning for abuse. A PubMed search of MeSH terms (addiction, substance) AND (hemophilia) reveals 212 studies, most of which are irrelevant to hemophilia or discuss substance abuse-related infections such as HIV and HCV. Only one study discusses the coping mechanism of HIV PWH, which was from 1996. The relevant studies to this research paper are compared and discussed below. Beyond biomedical drivers, psychosocial factors such as loneliness and interpersonal difficulties are consistently linked with addictive behaviors. In a large university sample, loneliness and interpersonal problems independently predicted higher addiction severity, even after adjustment for demographics, highlighting social-psychological mechanisms that may generalize to chronic-illness populations who face isolation and functional limitations (26).

According to our results, the prevalence of SUDs among PWH was 35%. Noorbala et al. assessed the prevalence of drug and alcohol abuse (using the ASSIST Questionnaire) in a normal population in Iran. The results showed that the rates of opioids and alcohol were 4.6% and 1.9%, respectively (27), meaning the rate of drug abuse in our studied population is much higher compared to the normal population. Similar to our findings, other studies have shown that chronic medical conditions are associated with higher rates of substance abuse, and the number of chronic diseases increases the odds of substance abuse disorder (28-30). To this end, we recommend that healthcare providers be aware of safe and affordable treatment options to prevent opioid dependence and drug addiction. Older age, male gender, and lower education level were more associated with drug dependence. This relationship was expected as it has been shown in the general population in Iran (31, 32). Interestingly, a positive family history had a significant impact on substance abuse dependence, suggesting the importance of family and social factors. The importance of these findings becomes even clearer as drug use is more prevalent in Sistan and Baluchistan compared to other provinces. In addition, hemophilia-related factors, such as type of factor deficiency, number of painful joints, and hemophilia-related pain (especially arthropathy), were significantly related to the percentage of patients with substance abuse. Similarly, Pinto et al. also reported a higher frequency of pain in type A PWH than in type B patients (33). However, there appears to be a great need for further research into pain management options for different types of hemophilia.

Considering the socio-economic status of Sistan and Baluchistan (the most deprived province in Iran) and a lack of medical facilities and psychological support dedicated to substance abuse disorder, PWH may seek unconventional ways to relieve their pain. Additionally, the availability of various addictive substances in Iran, especially in Sistan and Baluchistan province, may increase the PWH’s desire for substance abuse. Therefore, we recommend that patients and their families be educated on the complications of hemophilia (especially painful manifestations) so that if they occur and progress, appropriate treatments can be implemented by the medical centers.

Although our findings provide valuable insight into substance abuse behaviors among PWH in southeastern Iran, the results may not be fully generalizable to other regions or countries. Cultural norms, healthcare infrastructure, and access to pain management and rehabilitation services vary substantially across settings, which can influence both pain coping mechanisms and substance use patterns. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these results to broader or more diverse populations. Our observation that pain burden and social context shape substance use risk in PWH aligns with evidence that addiction vulnerability is amplified by loneliness and interpersonal problems. In analogous populations, residence away from family and weaker social ties correlate with greater addiction severity, and hierarchical models identify loneliness and interpersonal difficulties as independent predictors. These pathways are plausible in PWH who experience pain, functional limits, and restricted social participation (26).

Interventions that explicitly strengthen social support and address emotional coping may therefore be relevant for PWH with substance use risk. A recent systematic review of psychosocial rehabilitation in addiction highlights three leverage points: Involvement of partners/significant others, structured emotional-support therapies, and deliberate reinforcement of recovery-oriented social networks. While pooled effects across modalities are heterogeneous, compassion-focused therapy shows a strong, consistent signal; acceptance and commitment therapy and CBT show mixed results likely driven by content and delivery differences. Programs that build supportive networks and target shame, self-criticism, and coping skills could be adapted to hemophilia care pathways (34).

For future studies, we suggest well-categorized substances of abuse, a higher number of patients, reasoning for abuse, and choice of substance along with a control group for risk assessment. We also recommend prospective measurement of loneliness and interpersonal problems as candidate psychosocial predictors and targets, given their independent association with addiction severity in non-hemophilia cohorts (34). Studies from different populations on this topic can lead to a systematic patient-based approach to address the psychological and physical aspects of addiction in hemophilia patients. Given the high heterogeneity in psychosocial intervention outcomes, translating these approaches to PWH will require standardized protocols, attention to local resources, and monitoring of social-support engagement as an implementation outcome (34).

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, there is a need to develop a specific and systematized protocol for the prevention and treatment of drug abuse and dependence in PWH in Iran.