1. Background

Addiction is a serious disorder with significant physical, emotional, and social consequences. It is characterized by a loss of control, continued use despite adverse outcomes, and the presence of withdrawal symptoms when attempting to reduce or cease use (1). This condition can lead to a diminished quality of life and impair functioning across various domains of daily living (2).

Over the past few decades, various drug interventions have been attempted to reduce the effects of methamphetamine abuse and promote harm reduction. Despite some studies showing promising results, a recent systematic review indicated that psychostimulants do not have a significant effect on sustained abstinence or treatment retention (3). Also, psychological therapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing, and contingency management, generally show small to moderate short-term benefits over inactive controls, with effects often diminishing over time or after treatment ends (4).

Addiction often creates a self-reinforcing cycle that is difficult to break. Research suggests that treatment-seeking behaviors can disrupt this cycle, helping people improve and stay drug-free over time (5). It is shown that craving plays an important role in perpetuating addiction by reinforcing the cycle (6). Craving is typically defined as a persistent and intense urge to use a substance or engage in a specific behavior, serving as a strong motivational force that drives substance-seeking behavior. Cravings can be triggered by a variety of cues, including environmental stimuli, emotional states (such as stress or boredom), and social situations (7). Craving may manifest in both physical and psychological forms. Physical manifestations may include restlessness, perspiration, and elevated heart rate, whereas psychological manifestations often encompass intrusive thoughts, obsessive rumination, and fantasies related to substance use or other addictive behaviors (8). So, implementing a structured treatment plan that integrates targeted interventions for craving management is critical to sustaining abstinence and mitigating the risk of relapse (6). Recent clinical evidence also supports the effectiveness of novel adjunctive interventions, such as caffeine-based pharmacological strategies, in reducing craving and preventing relapse in individuals with methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) (9).

Previous research has demonstrated that methamphetamine use and associated behaviors cause disruptions in the brain’s reward circuitry (10). The reward circuitry comprises a network of brain structures that mediate pleasure and motivation (11). Imaging studies have shown that engaging in rewarding activities — such as drug use, gambling, or consuming palatable foods — triggers dopamine release in the brain. This dopaminergic activity produces a temporary sense of pleasure, reinforces the behavior, and increases the likelihood of its repetition (12). Disruption of the reward circuitry through methamphetamine use leads to long-term reductions in the expression of dopaminergic D2 receptors, thereby diminishing sensitivity to natural rewards and heightening cravings for drug-related stimulants. Understanding the role of dopamine in craving has significant implications for addiction treatment. For example, administration of high doses of dopamine antagonists has been found to help extinguish drug-seeking behaviors in methamphetamine users (13).

Thus, dopamine-mediated changes in the brain’s reward circuitry, which influence craving, play a critical role in relapse prevention strategies. Dopamine is produced by dopaminergic neurons in the brainstem and projects to the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (14). The PFC is involved in higher-order cognitive processes, particularly those modulated by dopaminergic activity. It has been suggested that one of the most important cognitive functions related to MUD and dopamine signaling in the reward circuitry is impulsivity (13). Impulsivity enables individuals to suppress inappropriate thoughts and urges, respond in a deliberate and adaptive manner, and is regulated by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (15). Research indicates that interventions targeting impulsivity can reduce craving in individuals with addiction (16, 17).

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a non-invasive technique that delivers low-level direct electrical current to the cerebral cortex through the scalp. By facilitating neuronal depolarization and hyperpolarization, tDCS can modulate neural excitability and enhance neuroplasticity. This method holds promise for improving cognitive functions and reducing drug cravings by altering brain activity patterns. It has been suggested that tDCS interventions targeting the DLPFC may specifically reduce impulsivity (18).

Given the significant challenges associated with MUD and the absence of a single, definitive treatment or pharmacological interventions (19), several studies have explored the use of tDCS on the DLPFC to reduce craving in individuals with MUD (8, 17, 20, 21). The first study, conducted by Rohani Anaraki et al., applied tDCS for five sessions on 15 individuals with MUD, assessing its effects on craving (17). Another study by Jiang et al. employed tDCS to reduce behavioral impulsivity by stimulating the right DLPFC for five consecutive days in 25 individuals with MUD, using both a sham and a healthy control group (20). Sharifat et al.'s study, on the other hand, assessed the effects of a single tDCS session on 15 individuals with MUD, measuring craving levels before and after stimulation (21). A subsequent study by Xu et al. used a larger sample size (23 participants in each group) and combined tDCS with computerized cognitive rehabilitation (8). This study assessed attention, impulsivity, working memory, and affect after 20 tDCS sessions (four sessions per week) with follow-up assessments at 2 and 4 weeks.

All of these studies targeted the PFC, positioning the anode on the right DLPFC and the cathode on the left DLPFC, which is considered the optimal and most frequently used electrode placement, as indicated by a meta-analysis (22). However, previous research has highlighted the lack of a consistent protocol and assessment methods for evaluating the effects of tDCS. Many studies also neglect the importance of follow-up evaluations and relapse assessment using validated methods. Furthermore, most studies do not fully address cognitive functions, particularly impulsivity, which plays a central role in craving, nor do they adequately consider emotional and affective aspects of substance use disorders (SUDs).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to build upon previous protocols by specifically focusing on relapse prevention, craving reduction, and the role of impulsivity and affect in individuals with MUD. Additionally, we aim to assess whether these factors are associated with relapse, providing a more comprehensive understanding of tDCS as a potential intervention for MUD.

3. Patientes and Methods

3.1. Participants

A total of 20 participants who used methamphetamine and were hospitalized during 2024 were recruited for the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Participants had to have recovered from the acute phase of methamphetamine use and completed detoxification after at least one week of hospitalization. Participants were required to have no prior experience with tDCS treatment. A diagnosis of MUD, based on DSM-5 criteria. Exclusion criteria included individuals with a history of head trauma, major neurological disorders (e.g., epilepsy, brain surgery, tumors, intracranial metal implants), or methamphetamine-induced disorders. Additionally, participants who continued methamphetamine use during the study were excluded. All participants received standard hospital care for MUD, including detoxification and general psychiatric support. No concurrent pharmacological or behavioral interventions specifically targeting craving, impulsivity, or affect were administered during the study period. Any influence of other treatments was thus expected to be similar across the real and sham tDCS groups.

3.2. Sample size

Based on a recent meta-analysis by Sahaf et al. (22), we performed a sample size calculation using G*Power software. For the planned F-test [analysis of variance (ANOVA): Repeated measures within-between subjects], we applied an effect size of 0.64, an alpha level of 0.05, and a power of 0.95, with 3 measurements and 2 groups. The calculation indicated that a total of 20 participants would be sufficient to detect a significant effect.

3.3. Materials

Desire for Drug Questionnaire (DDQ): This questionnaire, designed by Franken et al. focuses on craving as a motivational state and measures the craving for substances in the present moment. It consists of 14 questions, divided into three factors: The first factor, "desire and intention," includes questions 1, 2, 12, and 14; the second factor, "negative reinforcement," reflects the belief that substance use helps alleviate life problems and provides pleasure, and includes questions 5, 9, 11, 4, and 7; the third factor, "Loss of Control," includes questions 3, 8, 6, 10, and 13. Franken and colleagues reported an overall reliability of 0.85 for the questionnaire using Cronbach’s alpha, with subscale reliabilities of 0.77, 0.80, and 0.75, respectively (23). Internal consistency in a study by Hassani-Abharian et al. among users of various opioids, including crack and heroin, was 0.89, 0.79, and 0.40, while among methamphetamine users, it was 0.78, 0.65, and 0.81 (24).

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: The Barratt Impulsivity Scale (BIS) consists of 30 items rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from "never" = 1 to "always" = 4. The content of this questionnaire is summarized in three factors from the original version of the tool: Lack of planning, motor impulsivity, and cognitive impulsivity. Impulsivity due to lack of planning reflects a disregard for future consequences in one's behavior and actions. Motor impulsivity, on the other hand, involves acting without thinking or considering the consequences. Cognitive impulsivity refers to the ability to tolerate complexity and resist delays in decision-making situations (25). The coefficient was 0.8, and the test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.79 (26).

Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): This scale was developed in 1988 by Watson et al. to measure two dimensions: Negative affect and positive affect. It consists of 20 items, with a 5-point Likert scale for each item, ranging from "very little" (score 1) to "very much" (score 5), and is rated by the participant. The internal consistency for the positive affect subscale is 0.88, and for the negative affect subscale, it is 0.87. Test-retest reliability was reported as 0.68 for the positive affect subscale and 0.71 for the negative affect subscale (27, 28).

3.4. Procedure

In this study, 20 patients with MUD, having completed the acute phase of their illness and spent at least one week in a psychiatric hospital, were recruited through convenience sampling and referred to the Research Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. Following confirmation of the diagnosis by a specialized psychiatrist and obtaining informed consent, eligible individuals were enrolled in the study. The tDCS intervention commenced during their hospitalization.

Participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (real tDCS) or the control group (sham tDCS) using a block randomization method with a 1:1 allocation ratio. A total of 20 random allocation codes were generated using Microsoft Excel and placed in sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes to ensure allocation concealment. Upon enrollment, each participant was assigned to a group by opening the next envelope in sequence. Group allocation was performed by a researcher who was not involved in the assessment or intervention procedures.

The intervention consisted of 10 consecutive days of tDCS, using a 2 mA current delivered through 5 × 5 cm electrodes. Following the EEG 10 - 20 system, the anodal electrode was placed over F4 (right DLPFC) and the cathodal electrode over F3 (left DLPFC). In the intervention group, the current was gradually ramped up over 30 seconds, maintained at 2 mA for 20 minutes, and then ramped down over 30 seconds. In the sham group, a brief 30-second current was applied and then discontinued without participant awareness.

Assessments were conducted at four time points: Pre-test (T0), after the fifth session (T1), after the tenth session (T2), and at a two-week follow-up (T3). At each time point, the DDQ, BIS, and PANAS scales were administered. Psychiatric interviews were conducted throughout the study to monitor relapse.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26). The independent t-test was used to compare continuous demographic variables between groups, while the chi-square test was applied for categorical variables. To evaluate changes in craving, impulsivity, and affect over time and between groups, repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with time (T0, T1, T2, T3) as the within-subject factor and group (real tDCS vs. sham) as the between-subject factor. The interaction effect of time × group was examined to assess differential treatment effects. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups in demographic parameters.

Abbreviation: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

at-test.

b Chi square test.

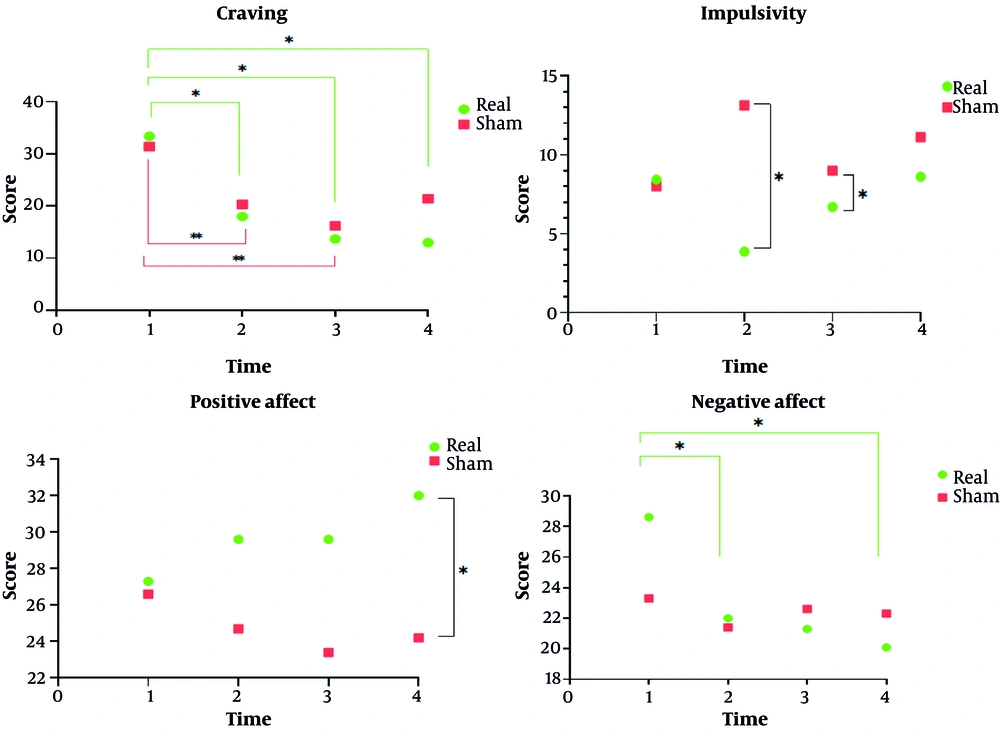

Table 2 presents the repeated measures of craving, impulsivity, and affect in participants with MUD across four time points. Craving scores decreased over time in both the real and sham tDCS groups, with the real tDCS group showing a larger reduction from pre-test (33.4 ± 18.73) to follow-up (13.0 ± 16.22). Impulsivity, assessed across non-planning, motor, attentional, and total score subscales, showed minimal differences between groups, with no significant time × group interactions observed. Positive affect increased slightly in the real tDCS group from 27.3 ± 2.24 at pre-test to 32.0 ± 2.24 at follow-up, while negative affect decreased modestly from 28.6 ± 3.02 to 20.1 ± 2.24. Statistical analysis indicated significant effects of time for some measures, whereas group effects and time × group interactions were generally non-significant (Figure 1).

| Scales and Stimulations | Pre-test | 5th Session | Post-test | Follow-up | Time | Group | Time × Group | Effect Size (η²p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craving | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.45 | ||||

| Real | 33.4 ± 18.7 (20.0 - 46.8) | 18.0 ± 12.3 (9.2 - 26.8) | 13.7 ± 14.0 (3.7 - 23.7) | 13.0 ± 16.2 (1.4 - 24.6) | ||||

| Sham | 31.4 ± 21.5 (16.0 - 46.8) | 20.3 ± 19.7 (6.2 - 34.4) | 16.2 ± 17.6 (3.6 - 28.8) | 21.4 ± 18.9 (7.9 - 34.9) | ||||

| Impulsivity | ||||||||

| Non-planning | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 0.004 | ||||

| Real | 22.40 ± 2.27 (20.77 - 24.02) | 20.50 ± 4.17 (17.51 - 23.48) | 22.00 ± 2.79 (20.00 - 23.99) | 21.30 ± 1.77 (20.03 - 22.56) | ||||

| Sham | 20.90 ± 2.92 (18.8 - 22.99) | 18.10 ± 4.70 (14.73-21.46) | 19.80 ± 3.52 (17.29 - 22.31) | 18.90 ± 4.56 (18.90 - 15.64) | ||||

| Motor | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.097 | ||||

| Real | 32.40 ± 4.65 (32.40 - 35.72) | 31.00 ± 3.30 (28.63 - 33.36) | 32.40 ± 4.48 (29.19 - 35.60) | 30.50 ± 6.67 (25.78 - 34.41) | ||||

| Sham | 31.00 ± 6.51 (26.33 - 35.66) | 25.50 ± 6.74 (20.68 - 30.31) | 26.60 (4.81 (23.15 - 30.04) | 30.10 ± 6.03 (25.72 - 35.27) | ||||

| Attentional | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.023 | ||||

| Real | 10.40 ± 2.63 (8.51 - 12.28) | 11.40 ± 3.47 (8.91 - 13.88) | 10.00 ± 1.33 (9.04 - 10.95) | 10.40 ± 2.80 (8.39 - 12.40) | ||||

| Sham | 8.10 ± 2.38 (6.39 - 9.80) | 8.00 ± 3.40 (5.56 - 10.43) | 8.40 ± 2.41 (6.67 - 10.12) | 8.60 ± 2.76 (6.62 - 10.57) | ||||

| Totla | 0.57 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.04 | ||||

| Real | 65.20 ± 2.66 (59.16 - 71.23) | 62.90 ± 1.22 (60.13 - 65.66) | 64.40 ± 2.11 (59.60 - 69.19) | 61.80 ± 2.72 (55.63 - 67.96) | ||||

| Sham | 60.00 ± 2.53 (54.26 - 65.73) | 51.60 ± 4.15 (42.20 - 60.99) | 54.80 ± 2.84 (48.35 - 61.24) | 58.00 ± 4.23 (48.42 - 67.57) | ||||

| Affect | ||||||||

| Positive | 0.84 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.07 | ||||

| Real | 27.3 ± 2.24 (22.21 - 32.38) | 29.6 ± 2.53 (23.87 - 35.32) | 29.6 ± 1.62 (25.93 - 33.26) | 32.0 ± 2.24 (26.47 - 37.52) | ||||

| Sham | 26.6 ± 2.29 (21.40 - 31.79) | 24.7 ± 2.89 (18.16 - 31.23) | 23.4 ± 2.56 (17.59 - 29.20 | 24.2 ± 2.25 (19.08 - 29.30) | ||||

| Negative | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0.07 | ||||

| Real | 28.6 ± 3.02 (21.75 - 35.44) | 22.0 ± 2.12 (17.19 - 26.80) | 21.3 ± 2.99 (14.52 - 28.07 | 20.1 ± 2.24 (15.01 - 25.18) | ||||

| Sham | 23.3 ± 2.73 (17.11 - 29.48) | 21.4 ± 2.40 (15.94 - 26.85) | 22.6 ± 3.14 (15.49 - 29.70 | 22.3 ± 2.56 (16.48 - 28.11) |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD (95% CI).

5. Discussion

The results of the present study indicated a significant reduction in craving scores over time; however, no significant difference was observed between the groups. This suggests that the reduction in craving occurred similarly across both the intervention and control groups. While the real tDCS group showed a more pronounced reduction in craving, the difference between groups did not reach statistical significance. Regarding impulsivity and its subscales, the results revealed significant differences between the groups at T2 and T3, but these differences were not maintained at follow-up. In terms of positive affect, a significant difference between groups emerged at T0 and persisted through the follow-up phase, reaching statistical significance by the end of the study. On the other hand, although both groups showed a reduction in negative affect, no significant difference was observed between them.

As mentioned earlier, the results of previous studies on the effects of tDCS are highly inconsistent. Some studies suggest that tDCS can reduce craving (29), while others do not (30, 31). For instance, one study (30) reported that tDCS with a cathodal protocol on the right DLPFC and anodal stimulation on the left DLPFC did not significantly reduce substance craving in individuals with MUD. Additionally, a brain imaging study found no significant impact of active tDCS on craving reported by methamphetamine users compared to sham stimulation. Although brain activation in specific regions increased following active stimulation, there was no corresponding reduction in self-reported craving (31). It is important to consider that craving is a complex, multifactorial phenomenon influenced by psychological, environmental, and biological factors. As in a study (32), real tDCS significantly reduced craving in individuals with nicotine use disorder, but this reduction did not lead to a significant change in smoking behavior. In our study, due to the hospital treatment setting and reliance on self-reported assessments through questionnaires, the placebo effect was likely high, which may have contributed to the reduction in craving scores even in the sham group. However, a notable observation is the sustained reduction in craving scores within the real tDCS group during the follow-up phase (T4). This trend was contrasted with the sham group, where a relative increase in craving was observed at the same stage. Although this difference did not reach statistical significance, it holds clinical relevance, suggesting that tDCS may be effective in preventing relapse. While craving scores in the real tDCS group continued to decrease during follow-up, the sham group experienced a sudden increase, which could be attributed to the potential role of tDCS in relapse prevention.

In terms of impulsivity, the results indicated significant differences between groups across all subscales and the total score. Further analysis revealed that while the total impulsivity score significantly decreased in the real tDCS group, the difference between groups diminished at T3, and the effect was no longer significant at follow-up. These findings suggest that while real tDCS can rapidly reduce impulsivity, maintaining this effect over time presents a challenge. Participants in the real tDCS group generally experienced lower levels of impulsivity, highlighting the importance of continued interventions, such as tDCS, to consolidate treatment outcomes. The reduction in impulsivity, particularly in the attentional and planning subscales, may reflect notable improvements in executive functions. This is consistent with prior research indicating that tDCS, by stimulating prefrontal regions — particularly the DLPFC — can enhance behavioral inhibition and reduce impulsive behaviors (33). Given that impulsivity is a critical factor in relapse to substance use, its reduction could be pivotal in preventing relapse (29). However, similar studies in other disorders have shown that the effects of tDCS on impulsivity may not persist over time, emphasizing the need for additional interventions to achieve sustained results (34).

Regarding positive affect, the results indicated a significant difference between the two groups, with participants in the intervention group demonstrating higher positive affect scores compared to the control group. However, this difference was not sustained over time, and the interaction effect of time × group did not reach statistical significance. These findings suggest that tDCS may improve positive mood and enhance emotional regulation by increasing activity in prefrontal regions. However, our results also showed that the effect of real tDCS on positive affect became significant only at the follow-up stage, indicating that the impact of tDCS on emotion is not immediate (in contrast to its effect on impulsivity) and requires time to manifest. This effect was not observed in the sham group, further supporting the gradual and sustained nature of tDCS's influence on emotional regulation (35). Increased positive affect may serve as a protective factor against cravings, enhancing motivation for continued abstinence, which aligns with previous research showing that brain stimulation can facilitate the experience of positive emotions (36). In contrast, when examining negative affect, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant, both groups showed a significant reduction in negative affect scores over time. Notably, a more pronounced decrease in negative affect was observed in the intervention group, whereas the control group showed a trend toward an increase from baseline, although this difference was not significant in the between-group analysis. These results suggest that brain stimulation may have played a supplementary role in further reducing negative affect (37).

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and future research should include larger samples to assess the significance of the effects more robustly. Additionally, tDCS was administered immediately following one week of hospitalization. While this approach is novel and, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to explore tDCS in this context, it is important to consider the potential impact of the medications used by participants and the gap between the cessation of medication use and the initiation of tDCS. Future studies should examine the psychological factors influencing the outcomes and place greater emphasis on extended follow-up periods to evaluate the long-term effects of tDCS.

5.1. Conclusions

This hospital-based sham-controlled study suggests that tDCS may have potential as an adjunctive intervention for reducing craving and improving emotional regulation in individuals with MUD. The effects on impulsivity were more pronounced immediately post-intervention but were not consistently sustained over time. While the sample size was small and the follow-up period short, the findings highlight the feasibility and potential clinical relevance of tDCS in relapse prevention. Future studies with larger samples, extended follow-up, and standardized protocols are warranted to confirm the long-term efficacy and generalizability of tDCS in this population.