1. Background

Workplace violence (WPV) against healthcare workers is a major global public health problem that threatens workforce retention and patient care quality (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines WPV as "incidents where staff are abused, threatened, or assaulted in circumstances related to their work" (2). This includes physical violence, verbal abuse, sexual harassment, and psychological aggression (3). Medical interns are especially vulnerable due to their trainee status, limited experience, and unclear authority within hospital hierarchies (4).

Globally, healthcare workers face a 16 times higher risk of WPV than other professionals (5), with trainees disproportionately affected (6). Annual incidence rates are alarming, with systematic reviews estimating that 8 - 38% of healthcare personnel experience physical violence and 12 - 75% face verbal abuse each year (7). These rates are often higher in teaching hospitals; for example, 68% of interns in Turkey (8) and 72% in Pakistan (9) report WPV exposure.

This study uses the framework of the International Labor Office/World Health Organization/International Council of Nurses (ILO/WHO/ICN) Workplace Violence Questionnaire (10). This framework views WPV as resulting from a combination of individual, perpetrator, organizational, and socio-environmental factors. It provides a structure to analyze the types of violence, perpetrator characteristics, institutional context, and impacts on health workers.

In Iran, factors like economic instability, healthcare system pressures, and patient dissatisfaction have led to more WPV incidents (11). National studies show that 45 - 53% of Iranian physicians and trainees experience verbal or physical violence (12-15). However, underreporting is severe. For instance, 78% of interns in Tehran's teaching hospitals did not report incidents, mainly due to fears of academic retaliation (16).

Beyond physical harm, WPV causes significant psychological damage to trainees, leading to anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress (16). These effects often reduce clinical performance and care quality (17), and contribute to early career burnout and attrition (18). A 2023 meta-analysis found that 86% of affected healthcare workers had psychological symptoms lasting over six months (19). Workplace violence also has high institutional costs from staff turnover, lost productivity, and malpractice risks (20).

Despite existing evidence, a key gap remains: There is little understanding of how local sociocultural and institutional factors shape WPV in underserved regions like Sistan and Baluchestan Province. Previous Iranian studies mainly report national prevalence, but lack a detailed analysis of how ethnic diversity, local gender norms, and specific institutional cultures affect WPV dynamics against interns.

Therefore, this study addresses this gap. We used the ILO/WHO/ICN Questionnaire to examine WPV prevalence, types, and associated factors among medical interns at Zahedan University. We specifically investigated how local sociocultural factors (e.g., ethnicity, gender) and organizational determinants influence WPV risk and experience. This approach provides a nuanced, theory-based analysis to inform preventive programs in this high-risk setting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This study employed a cross-sectional (descriptive-analytical) design. The target population consisted of medical internship students at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences during the academic year 2023 - 2024.

Inclusion criteria were: Medical interns who had completed at least one 6 months clinical rotation in Zahedan’s teaching hospitals, and willingness to participate in the study. A census sampling approach was initially planned. During the study, 248 interns were present, with at least 6 months of internship. However, due to eligibility requirements (willingness to participate, and absence of leave), the final sample comprised 200 medical interns from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences in 2023 - 2024.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (ethical code: IR.ZAUMS.REC.1401.376). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. Interns received explanations about the study’s purpose, voluntary participation, and data confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained before distributing questionnaires.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected using: Demographic information (age, gender, rotation department, and duration of internship) and the Workplace Violence in the Health Sector Questionnaire, developed by the ILO, WHO, and ICN (10). This questionnaire contains 53 items across four domains: Physical violence (15 items), verbal violence (13 items), sexual violence (12 items), and racial/ethnic violence (12 items), and an additional section: 16 items on responses to violence and suggested interventions.

To assess content and face validity, the Persian version of the questionnaire was reviewed and approved by a panel of 11 experts, including four nurses, two psychologists, two psychiatrists, one social worker, and two nursing managers. The experts evaluated the questionnaire for clarity, relevance, and cultural appropriateness, and their recommendations were incorporated. The Content Validity Index (CVI) and Content Validity Ratio (CVR) were calculated and found to be within acceptable ranges (CVI > 0.80 and CVR > 0.78), confirming the adequacy of the instrument’s validity. To determine reliability, the questionnaire was administered to 180 health professionals twice with a 15-day interval. The test-retest correlation coefficient was r = 0.71, indicating acceptable reliability of the instrument (14).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v.26. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage) summarized baseline characteristics. In order to determine predictors of WPV against medical interns, first, we performed univariate analysis (χ², independent t-test) and variables that were statistically significant were included in the logistic regression model, with a significance level set at 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 200 medical interns participated in the study, with a nearly equal gender distribution and a mean age of 25.31 ± 2.58 years. The sample was drawn from various rotation departments, with internal medicine being the most common (25%), as detailed in the participant characteristics.

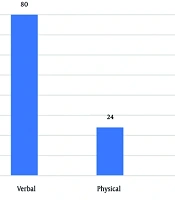

Workplace violence was highly prevalent among the interns. Verbal abuse was the most common form (80%), followed by physical (24%), ethnic (23.5%), and sexual violence (12%). Patient relatives were the most frequently reported perpetrators for physical and verbal violence.

Statistical analyses revealed significant associations between WPV types and demographic/work-related factors. A strong gender disparity was observed (Table 1). Female interns reported significantly higher rates of physical violence (32.1% vs. 13.6% in males, P = 0.002) and were disproportionately affected by sexual violence (20.5% vs. 1.1%, P < 0.001). In contrast, no significant gender differences were found for verbal or ethnic violence.

| Type of Violence, Gender | Yes | No | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | 0.002 | |||

| Male | 12 (13.6) | 76 (86.4) | 88 (100.0) | |

| Female | 36 (32.1) | 76 (67.9) | 112 (100.0) | |

| Verbal | 0.569 | |||

| Male | 72 (81.8) | 16 (18.2) | 88 (100.0) | |

| Female | 88 (78.6) | 24 (21.4) | 112 (100.0) | |

| Sexual | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 1 (1.1) | 87 (98.9) | 88 (100.0) | |

| Female | 23 (20.5) | 89 (79.5) | 112 (100.0) | |

| Ethnic | 0.572 | |||

| Male | 19 (21.6) | 69 (78.4) | 88 (100.0) | |

| Female | 28 (25.0) | 84 (75.0) | 112 (100.0) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

A longer internship duration was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of experiencing verbal, sexual, and ethnic violence (Table 2). Furthermore, the clinical environment and internship duration were also critical factors. Interns in the Emergency Department experienced a significantly higher incidence of physical violence compared to those in hospital wards (32.3% vs. 12.6%, P < 0.001), as shown in Table 3. No significant variations in WPV were found across different shift times.

| Type of Violence | Values | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Internship duration (mo); mean ± SD | ||

| Physical | 0.986 | |

| Yes (n = 48) | 10.58 ± 3.93 | |

| No (n = 152) | 10.59 ± 2.57 | |

| Verbal | 0.002 | |

| Yes (n = 160) | 10.91 ± 2.98 | |

| No (n = 40) | 9.30 ± 2.43 | |

| Sexual | < 0.001 | |

| Yes (n = 24) | 15.20 ± 1.79 | |

| No (n = 176) | 9.95 ± 2.46 | |

| Ethnic | 0.034 | |

| Yes (n = 47) | 11.38 ± 3.01 | |

| No (n = 153) | 10.34 ± 2.89 |

| Variables | Physical (N = 48) | Verbal (N = 160) | Sexual (N = 24) | Ethnic (N = 47) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift time | 0.533 | ||||

| Morning | 15 (20.0) | 44 (58.7) | 3 (4.0) | 13 (17.3) | |

| Afternoon | 9 (17.3) | 32 (61.5) | 3 (5.8) | 8 (15.4) | |

| Night | 24 (15.8) | 84 (55.3) | 18 (11.8) | 26 (17.1) | |

| Department | < 0.001 | ||||

| Hospital ward | 27 (12.6) | 130 (60.7) | 19 (8.9) | 38 (17.8) | |

| Emergency | 21 (32.3) | 30 (46.2) | 5 (7.7) | 9 (13.8) |

a Values are expresses as No. (%).

Multivariable logistic regression (backward conditional model) confirmed these patterns (Table 4). Key predictors included:

- Physical violence: Female gender (OR = 2.62) and assignment to the Emergency Department (OR = 3.97).

- Sexual violence: Female gender was the strongest predictor (OR = 34.96), along with a longer internship duration (OR = 3.20).

- Verbal and ethnic violence: A longer internship duration was a significant risk factor for both (OR = 1.23 and OR = 1.13, respectively).

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical violence | |||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 2.620 | 1.241 - 5.530 | 0.012 |

| Department (emergency vs. hospital ward) | 3.970 | 1.746 - 9.028 | 0.001 |

| Verbal violence | |||

| Duration of internship (for each month of increase in the internship period) | 1.229 | 1.076 - 1.404 | 0.002 |

| Sexual violence | |||

| Gender (female vs. male) | 34.957 | 3.420 - 357.310 | 0.003 |

| Duration of internship (for each month of increase in the internship period) | 3.201 | 1.984 - 5.165 | < 0.001 |

| Ethnic violence | |||

| Duration of internship (for each month of increase in the internship period) | 1.127 | 1.007 - 1.261 | 0.037 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Model fit statistics: Physical violence model: Nagelkerke R² = 0.15, Hosmer-Lemeshow test P-value = 0.45; verbal violence model: Nagelkerke R² = 0.08, Hosmer-Lemeshow test P-value = 0.62; sexual violence model: Nagelkerke R² = 0.28, Hosmer-Lemeshow test P-value = 0.18; ethnic violence model: Nagelkerke R² = 0.05, Hosmer-Lemeshow test P-value = 0.71.

b All models were adjusted for all other variables in the table using a backward conditional selection method. The variance inflation factor (VIF) for all predictors was below 2.5, indicating no substantial multicollinearity. The wide confidence interval for gender in the sexual violence model is likely due to the low number of reported cases in the male group.

Regarding responses to WPV, the most common action was self-defence (29.0%), while 28.5% took no action. The primary reason for not reporting incidents was the belief that reporting would be futile (39.63%).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

The data indicate that verbal abuse was the most common form of WPV (80%), followed by physical (24%), ethnic (23.5%), and sexual violence (9%). Regression analysis identified female gender and assignment to emergency departments as significant predictors of physical violence, while a longer internship duration increased the risk of non-physical abuse. A critical finding was the profound underreporting of incidents, with only 28.5% of affected interns formally reporting their experiences.

4.2. Interpretation and Comparison with Literature

Our findings align with global and national studies. Verbal aggression is the most common form of WPV in healthcare environments (3, 9). This pattern is well-established; a 2024 systematic review confirmed verbal abuse as the most prevalent form, with rates as high as 97% (21, 22). In our context, this high prevalence may be linked to the hierarchical hospital culture and the low status of medical interns, who are often targets for frustration from systemic issues like overcrowding. This normalization of verbal abuse indicates a critical institutional failure to ensure a respectful workplace.

The frequency of physical assaults among interns in our study (24%) aligns with rates reported internationally, ranging from 20 - 30% (6, 23, 24). As consistently reported, emergency departments pose the highest risk due to high patient volumes and emotionally charged encounters (8, 25). In southeastern Iran, this risk may be heightened by limited public trust in the health system and the high-stress environment of a resource-limited region.

Although less physically harmful, verbal abuse significantly contributes to psychological exhaustion, burnout, and reduced job satisfaction. These factors are linked to increased medical errors and attrition (16, 17). Therefore, preventive frameworks must target psychological well-being as a core component of institutional support, not just as a remedy.

Sexual harassment affected 9% of respondents, with female interns disproportionately targeted. This mirrors findings from other Iranian studies (13-15) and underscores persistent gender-based power imbalances in medical education (18). Analytically, this is not an isolated issue but a manifestation of patriarchal norms intersecting with institutional hierarchy, leaving female trainees vulnerable without adequate recourse.

Ethnic violence was reported by nearly one-quarter of participants, a relatively underexplored form of WPV in Iran. Given the sociocultural diversity of Sistan and Baluchestan province, these findings highlight the potential role of ethnic tension in hospital dynamics (20, 24). This demands a specific organizational response, including intercultural training and explicit inclusion of ethnic discrimination in anti-violence policies.

Regression analysis revealed that female gender and working in emergency departments predicted physical violence, while longer internship duration increased vulnerability to non-physical abuse. This confirms that risk is not random but structured by identifiable factors, allowing for targeted interventions (6, 12).

Alarmingly, only 28.5% of affected interns formally reported violent incidents. This severe underreporting matches patterns in other Iranian studies (15, 22, 25) and reflects systemic failures globally (26). Common barriers include fear of retaliation, lack of clear reporting systems, and the normalization of violence (27). This underreporting itself is a symptom of the absence of a trusted, effective institutional framework for protection and justice.

4.3. Conclusions

Workplace violence represents a pervasive threat to medical interns in southeastern Iran. Gender, workplace setting, and training duration emerged as key determinants of risk. Institutional and systemic interventions — grounded in global best practices and supported by WHO guidelines — are essential to foster safe, equitable, and supportive clinical learning environments for medical trainees.

4.4. Implications

Our findings emphasize the need for multi-level interventions. We propose a framework that moves beyond generic recommendations: Institutionally, hospitals should establish clear anti-violence policies, confidential reporting mechanisms, and ensure systematic follow-up. This must include specific protocols for gender-based and ethnic violence. Educational reforms should incorporate WPV prevention into undergraduate and internship curricula, focusing on de-escalation and trainee rights (8). At the policy level, alignment with the WHO's Framework Guidelines can provide a comprehensive national framework (2). Furthermore, enhancing psychological support — particularly in high-stress regions like southeastern Iran — can mitigate negative mental health impacts (28).