1. Background

In December 2019, the world faced a critical new public health stressor with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. The disease spread so rapidly that it impacted the management of healthcare in countries around the world for weeks (1, 2). The COVID-19 pandemic has created new situations that require effective communication of health information worldwide. Providing clear, consistent, and trustworthy information about the pandemic is crucial to contain and control the pandemic (3). It is important to use fast, reliable sources of information (4). The importance of effective communication strategies to improve the population's level of information has been demonstrated in recent years with the outbreak of epidemics such as Ebola, Zika, influenza, and dengue fever (5). Reliable and well-selected health information sources can increase people's knowledge and thus improve their health beliefs and affect their precautions (6, 7). On the other hand, mistrust of information sources can also harm audience acceptance (7). For emerging diseases, unlike chronic diseases, there is no scientific certainty about the information associated with the disease due to a lack of access to medical and public health information, and the existence of numerous and diverse channels complicates this problem (8). The uniqueness of this study lies in the examination of these dynamics among Iranian university students, a population with high digital literacy but facing unique cultural barriers to information trust.

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to identify the main sources of information used by students regarding COVID-19 and to evaluate their perceived reliability. The aim is to inform the development of effective health communication strategies specifically tailored to this population.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Population

This cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the STROBE guidelines for observational studies. The researchers designed the questionnaire based on literature sources (4, 9, 10). This survey was carried out from July to November 2020. The study employed a convenience sampling method. Inclusion criteria included university students aged 18 years or older with access to online platforms and a willingness to participate. Exclusion criteria were incomplete responses. To mitigate selection bias and enhance the diversity of the sample, the questionnaire was distributed across a wide range of university virtual groups, encompassing both medical and non-medical disciplines from various cities in Iran. To address potential sources of bias, such as self-selection bias, the survey was promoted neutrally without incentives, and efforts were made to reach underrepresented groups (e.g., non-medical students) through targeted virtual groups.

3.2. Setting

The questionnaire was disseminated online through virtual groups to students attending various universities (both medical and non-medical) across different cities in Iran.

3.3. Data Collection

The population of the study comprised students from various medical and non-medical universities in Iran. Employing Krejcie and Morgan's table (11), the initial sample size was calculated at 384 students. The data collection concluded after 400 questionnaires were collected to account for possible losses. Subsequently, nine incomplete questionnaires were excluded, leaving 391 questionnaires for statistical analysis. The proportion of missing data was 2.25% (9 out of 400). The study employed convenience sampling, selecting participants based on accessibility and ease of engagement, excluding incomplete questionnaires from the analysis. After data collection, nine questionnaires with missing data in the core sections were excluded from the analysis to ensure data integrity, resulting in a final sample of 391 complete questionnaires for analysis.

3.4. Research Instrument

An online questionnaire was administered to gather data. Its sections comprised an introduction delineating the study objectives, followed by recording sociodemographic variables (e.g., sex, age, major, education level, grade point average (GPA), marital status, medical/non-medical university, and personal facilities). The subsequent segment encompassed four questions and 60 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (high, medium, low, and not at all). This section evaluated sources of COVID-19-related information (15 items), confidence levels in these sources (15 items), their perceived usefulness (15 items), and convenience/ease of access (15 items). Outcome measures included the percentage of participants rating each source as "high" for usage, trust, usefulness, and convenience. The completion time for the survey averaged around 10 minutes. The questionnaire underwent content and face validity checks via expert panel assessment. Following this, a pilot study involved 10 students to assess the questionnaire's internal consistency and reliability. The computed Cronbach's alpha, a measure of reliability, exhibited a satisfactory value of 0.82, surpassing the acceptable threshold of 0.70.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. The analysis was performed on complete cases; questionnaires with any missing data were excluded. Given the descriptive aims of the study, the data were summarized using descriptive statistics, presented as frequencies and percentages. Missing data were handled by complete-case analysis, as the exclusion rate was low (2.25%) and unlikely to introduce substantial bias in this descriptive context.

4. Results

The study sample consisted of 391 university students, mainly from medical sciences backgrounds, with an average age of 25.13 ± 6.42 years. The majority of participants were female [245 (62.70%)], which is in line with the typical gender distribution in Iranian higher education. Most were married [311 (79.50%)], which may be influenced by cultural norms and the older age of undergraduate cohorts in the region. In terms of education, undergraduates were the majority [291 (74.40%)], while graduate students made up a smaller percentage [100 (25.60%)]. The field of study was heavily focused on medical sciences [328 (83.90%)], with non-medical sciences being less represented [63 (16.10%)], potentially impacting perceptions of health-related information sources. Table 1 offers a comprehensive summary of these demographic variables, including marital status, GPA, education level, and field of study.

| Demographic Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 146 (37.30) |

| Female | 245 (62.70) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 78 (19.90) |

| Married | 311 (79.50) |

| Other | 2 (0.50) |

| Education level | |

| Undergraduate | 291 (74.40) |

| Postgraduate | 100 (25.60) |

| GPA | |

| A | 228 (58.30) |

| B | 145 (37.10) |

| C | 18 (4.60) |

| Major | |

| Medical sciences | 328 (83.90) |

| Non-medical sciences | 63 (16.10) |

| Personal facilities | |

| Smart phone | 167 (42.70) |

| Cell phone | 4 (1.00) |

| Laptop | 132 (33.80) |

| PC | 53 (13.60) |

| Tablet | 35 (9.00) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 25.13 ± 6.42 |

Abbreviations: GPA, grade point average; PC, personal computer; SD, standard deviation.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

4.1. Sources of Information

The primary sources of information for students regarding COVID-19 included international messenger and social media platforms (37.60%), encompassing platforms like Instagram, Telegram, and WhatsApp. This was followed by domestic scientific websites (29.90%) such as the Ministry of Health, university websites, and research centers. Additionally, international scientific websites like the World Health Organization (WHO), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and National Institutes of Health (NIH, 27.90%), and healthcare workers like doctors and nurses (27.10%) were commonly used sources. Conversely, students did not utilize domestic messenger and social networks (Soroush, iGap, Eitaa, Bale, etc., 69.10%), celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. (67.30%), system respondents (4030, 190, 1666, My Doctor, etc., 57.00%), and foreign news networks [BBC News, cable news network (CNN), etc., 49.90%] for COVID-19 information (Table 2).

| Source of Information | High | Medium | Low | Not at all |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional media (TV, radio, newspaper, etc.) | 80 (20.50) | 136 (34.00) | 112 (28.60) | 63 (16.00) |

| Foreign news networks (BBC News, CNN, etc.) | 25 (6.40) | 63 (16.10) | 108 (27.50) | 195 (49.90) |

| Domestic scientific sites (Ministry of Health, sites of universities, research centers, etc.) | 117 (29.90) | 143 (36.60) | 88 (22.50) | 43 (11.00) |

| International scientific websites (WHO, CDC, NIH, etc.) | 109 (27.90) | 101 (25.80) | 116 (29.70) | 65 (16.60) |

| Scientific (Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, etc.) | 64 (16.40) | 99 (25.30) | 118 (30.20) | 110 (28.10) |

| News websites (IRNA, ISNA, YJC, etc.) | 24 (6.10) | 116(29.70) | 139 (35.50) | 112 (28.60) |

| International messengers and social media (Instagram, Telegram, WhatsApp, etc.) | 147 (37.60) | 139 (35.50) | 72 (18.40) | 33 (8.40) |

| Domestic messengers and social networks (Soroush, iGap, Eitaa, Bale, etc.) | 15 (3.80) | 34 (8.70) | 72 (18.40) | 270 (69.10) |

| Participate in scientific webinars and domestic or foreign virtual training courses | 24 (6.10) | 98 (25.10) | 112 (28.60) | 157 (40.20) |

| Family members, relatives, and acquaintances | 29 (7.40) | 123 (31.50) | 171 (43.70) | 68 (17.40) |

| Friends or classmates | 36 (9.20) | 162 (41.40) | 148 (37.90) | 45 (11.50) |

| University professors | 60 (15.30) | 140 (35.80) | 127 (32.50) | 64 (16.40) |

| Celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. | 18 (4.60) | 29 (7.40) | 81 (20.70) | 263 (67.30) |

| Health care workers (Physicians, nurses, etc.) | 106 (27.10) | 179 (45.80) | 83 (21.20) | 23 (5.90) |

| System respondents (4030, 190, 1666, my doctor, etc.) | 24 (6.10) | 50 (12.80) | 94 (24.0) | 223 (57.0) |

Abbreviations: TV, television; CNN, cable news network; WHO, World Health Organization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH, National Institutes of Health; IRNA, The Islamic Republic News Agency; ISNA, Iranian Students' News Agency; YJC, Young Journalists' Club.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.2. The Degree of Trust

According to the data, international scientific websites (57.80%) and scientific databases (44.00%) like Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science were deemed the most trustworthy sources of news and information by students. Conversely, students displayed a lack of trust in sources such as celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. (66.60%), international messengers, and social media platforms (52.70%), along with foreign news channels like BBC News, CNN, etc. (33.50%, Table 3).

| Source of Information | High | Medium | Low | Not at all |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional media (TV, radio, newspaper, etc.) | 75 (19.20) | 119 (30.40) | 118 (30.20) | 79 (20.20) |

| Foreign news networks (BBC News, CNN, etc.) | 32 (8.20) | 112 (28.60) | 116 (29.70) | 131 (33.50) |

| Domestic scientific sites (Ministry of Health, sites of universities, research centers, etc.) | 136 (34.80) | 176 (45.00) | 51 (13.00) | 28 (7.20) |

| International scientific websites (WHO, CDC, NIH, etc.) | 226 (57.80) | 115 (29.40) | 30 (7.70) | 20 (5.10) |

| Scientific (Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, etc.) | 172 (44.00) | 118 (30.20) | 63 (16.10) | 38 (9.70) |

| News websites (IRNA, ISNA, YJC, etc.) | 31 (7.90) | 149 (38.10) | 114 (29.20) | 97 (24.80) |

| International messengers and social media (Instagram, Telegram, WhatsApp, etc.) | 20 (5.10) | 58 (14.80) | 107 (27.40) | 206 (52.70) |

| Domestic messengers and social networks (Soroush, iGap, Eitaa, Bale, etc.) | 45 (11.50) | 149 (38.10) | 148 (37.90) | 49 (12.50) |

| Participate in scientific webinars and domestic or foreign virtual training courses | 72 (18.40) | 157 (40.20) | 103 (26.30) | 59 (15.10) |

| Family members, relatives, and acquaintances | 23 (5.90) | 97 (24.80) | 179 (45.80) | 92 (23.50) |

| Friends or classmates | 23 (5.90) | 145 (37.10) | 165 (42.20) | 58 (14.80) |

| University professors | 90 (23.00) | 182 (46.50) | 83 (21.20) | 36 (9.20) |

| Celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. | 21 (5.40) | 38 (9.70) | 95 (24.30) | 237 (60.60) |

| Healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, etc.) | 161 (41.20) | 154 (39.40) | 60 (15.30) | 16 (4.10) |

| System respondents (4030, 190, 1666, my doctor, etc.) | 66 (16.90) | 130 (33.20) | 76 (15.40) | 119 (30.40) |

Abbreviations: TV, television; CNN, cable news network; WHO, World Health Organization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH, National Institutes of Health; IRNA, The Islamic Republic News Agency; ISNA, Iranian Students' News Agency; YJC, Young Journalists' Club.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.3. The Degree of Usefulness

The data from participants highlighted the most valuable sources of COVID-19-related news and information, ranking international scientific websites (46.30%), healthcare workers (37.60%), domestic scientific websites (33.80%), and scientific databases (31.20%) as highly useful. Conversely, students deemed certain sources entirely invaluable, including celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. (63.90%), domestic messenger and social networks (59.60%), system respondents (39.60%), and foreign news networks (37.30%, Table 4).

| Source of Information | High | Medium | Low | Not at all |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional media (TV, radio, newspaper, etc.) | 80 (21.20) | 127 (32.50) | 122 (31.20) | 59 (15.10) |

| Foreign news networks (BBC News, CNN, etc.).) | 27 (6.90) | 108 (27.60) | 110 (28.10) | 146 (37.30) |

| Domestic scientific sites (Ministry of Health, sites of universities, research centers, etc.) | 132 (33.80) | 169 (43.20) | 52 (13.30) | 38 (9.70) |

| International scientific websites (WHO, CDC, NIH, etc.) | 181 (46.30) | 126 (32.20) | 47 (12.00) | 37 (9.00) |

| Scientific (Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, etc.) | 122 (31.20) | 108 (27.60) | 85 (21.70) | 76 (19.40) |

| News websites (IRNA, ISNA, YJC, etc.) | 32 (8.20) | 146 (37.30) | 115 (29.40) | 98 (25.10) |

| International messengers and social media (Instagram, Telegram, WhatsApp, etc.) | 91 (23.30) | 147 (37.60) | 110 (28.10) | 43 (11.00) |

| Domestic messengers and social networks (Soroush, iGap, Eitaa, Bale, etc.) | 34 (8.70) | 53 (13.60) | 71 (18.20) | 233 (59.60) |

| Participate in scientific webinars and domestic or foreign virtual training courses | 54 (13.80) | 127 (32.50) | 116 (29.70) | 94 (24.00) |

| Family members, relatives, and acquaintances | 33 (8.40) | 106 (27.10) | 161 (41.20) | 91 (23.30) |

| Friends or classmates | 31 (7.90) | 154 (39.40) | 145 (37.10) | 61 (15.60) |

| University professors | 82 (21.0) | 167 (42.20) | 89 (22.80) | 53 (13.60) |

| Celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. | 27 (6.90) | 38 (9.70) | 76 (19.40) | 250 (63.90) |

| Health care workers (physicians, nurses, etc.) | 147 (37.60) | 153 (39.10) | 72 (18.40) | 19 (4.90) |

| System respondents (4030, 190, 1666, my doctor, etc.) | 71 (18.20) | 85 (21.70) | 80 (20.50) | 155 (39.60) |

Abbreviations: TV, television; CNN, cable news network; WHO, World Health Organization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH, National Institutes of Health; IRNA, The Islamic Republic News Agency; ISNA, Iranian Students' News Agency; YJC, Young Journalists' Club.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.4. The Degree of Convenience and Ease

According to the students' perspectives, the most accessible sources for obtaining news and information were international messengers and social media (61.40%), along with traditional media like television (TV), radio, and newspapers (58.30%). Conversely, students found the following sources challenging to use: Domestic messenger and social networks (44.8%) and platforms involving celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. (41.7%, Table 5).

| Source of Information | High | Medium | Low | Not at all |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional media (TV, radio, newspaper, etc.) | 228 (58.30) | 108 (27.60) | 41(10.50) | 14 (3.60) |

| Foreign news networks (BBC News, CNN, etc.) | 76 (19.40) | 116 (29.70) | 87 (22.30) | 112 (28.60) |

| Domestic scientific sites (Ministry of Health, sites of universities, research centers, etc.) | 142 (36.30) | 184 (47.10) | 48 (12.30) | 17 (4.30) |

| International scientific websites (WHO, CDC, NIH, etc.) | 114 (29.20) | 168 (43.00) | 78 (19.90) | 31 (7.90) |

| Scientific (Google Scholar, PubMed, Science Direct, etc.) | 92 (23.50) | 140 (35.80) | 117 (29.90) | 42 (10.70) |

| News websites (IRNA, ISNA, YJC, etc.) | 120 (30.70) | 161 (41.20) | 71 (18.20) | 39 (10.00) |

| International messengers and social media (Instagram, Telegram, WhatsApp, etc.) | 240 (61.40) | 102 (26.10) | 35 (9.00) | 14 (3.60) |

| Domestic messengers and social networks (Soroush, iGap, Eitaa, Bale, etc.) | 68 (17.40) | 73 (18.70) | 75 (19.20) | 175 (44.80) |

| Participating in scientific webinars and domestic or foreign virtual training courses | 46 (11.80) | 127 (32.50) | 142 (36.30) | 76 (19.40) |

| Family members, relatives, and acquaintances | 132 (33.80) | 167 (42.70) | 58 (14.80) | 34 (8.70) |

| Friends or classmates | 127 (32.50) | 155 (39.60) | 88 (22.50) | 21 (5.40) |

| University professors | 87 (22.30) | 174 (44.50) | 98 (25.10) | 32 (8.20) |

| Celebrities, influencers, freelancers, etc. | 51 (13.00) | 89 (22.80) | 88 (22.50) | 163 (41.70) |

| Health care workers (physicians, nurses, etc.) | 122 (31.20) | 174 (44.50) | 75 (19.20) | 20 (5.10) |

| System respondents (4030, 190, 1666, my doctor, etc.) | 79 (20.20) | 130 (33.20) | 93 (23.80) | 89 (22.80) |

Abbreviations: TV, television; CNN, cable news network; WHO, World Health Organization; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; NIH, National Institutes of Health; IRNA, The Islamic Republic News Agency; ISNA, Iranian Students' News Agency; YJC, Young Journalists' Club.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

4.5. Summary of Key Findings

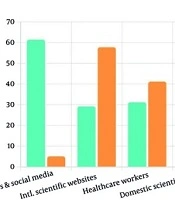

Figure 1 summarizes the key findings on convenience and trust across major sources, visually highlighting the paradox of high accessibility for social media contrasted with low trust levels.

Summary of key findings on accessibility vs. trust in COVID-19 information sources: Bars represent percentages of "high" ratings for convenience/accessibility (teal) and trust (orange) from Likert scale responses [data is from Tables 2 and 5 (n = 391); multiple responses are allowed; highlights paradox: High convenience (e.g., 61.4% for social media) vs. low trust (5.1%)].

5. Discussion

This study extensively explored COVID-19 information sources among students from various Iranian universities. The findings indicated that the primary sources of COVID-19 information for students were international messengers and social media, domestic scientific websites, international scientific websites, and healthcare workers. These results align with established patterns seen in the literature, emphasizing the prevalence of social media as the most frequently utilized information source among students (12-15) . Recent studies indicate a shift in preferred information channels during crises towards online news or social media (15-17). However, past epidemic research emphasizes the pivotal role played by traditional media like television and newspapers in heightening public awareness and shaping health issue comprehension (8, 18). Although social media can effectively promote preventive measures, the development of literacy skills is crucial for its optimal utilization. Further investigation is warranted to explore how specific social media platforms influence preventive behaviors, particularly in the context of misinformation, which was prevalent during the COVID-19 pandemic (19). Our findings highlight a novel paradox in Iranian students: High accessibility of social media but low trust, which contrasts with studies in Jordan, where social media was both primary and somewhat trusted (13). Similarly, in Palestine, Baker et al. reported trust in the WHO but reliance on social media, aligning with our emphasis on international sites (15). In Japan, Uchibori et al. found that traditional media is more trusted, suggesting cultural differences in digital adoption (19). Trust in information sources significantly impacts public responses, especially during health crises. Misleading information on vaccinations, deaths, and lockdowns can trigger panic buying of essential goods, disrupting supply chains (20). This study highlights the reliance on international scientific websites and databases by most participants, consistent with Friedman et al., who noted government sources like the CDC, FDA, and local health departments as most reliable for the general public (21). In contrast, Zhong et al. identified social media as a primary COVID-19 source for patients, with health professionals most trusted (22), while this study and a Saudi Arabian non-pandemic investigation revealed low trust in international messengers and social media, favoring healthcare professionals (6). This discrepancy suggests that while social media is accessible, its unverified content undermines trust, necessitating strategies such as collaboration with social media platforms to implement fact-checking algorithms and promote verified health information from sources like the WHO or CDC.

The study highlighted students' preference for international messengers, social media, and traditional media as the most accessible information sources. Another research indicated that social media, websites, and internet engines were also easily accessible (23). Notably, social media emerged as the most extensively used and convenient source in this study, but lacked trustworthiness. Given the study's focus on young people with high internet and social media usage, the unfiltered nature of news on these platforms led to skepticism regarding their reliability. To address this, policymakers should prioritize partnerships with social media platforms to enhance content moderation and promote credible sources, reducing the spread of misinformation that could exacerbate public health crises.

Interestingly, to our knowledge, few studies have specifically evaluated the perceived usefulness of information sources. However, the present study observed a pattern of alignment between trust and perceived usefulness. Across the data, sources rated highly for trustworthiness (e.g., international scientific websites) were consistently also rated highly for usefulness. This suggests that students may perceive trustworthy sources as more applicable to their needs. This descriptive observation underscores the potential interplay between trust and utility in health information seeking, warranting future correlational analyses.

5.1. Conclusions

The distribution of accurate information via trusted sources is pivotal for ensuring public adherence to crucial health guidelines. This study pinpointed international messengers and social media as the predominant and convenient sources of COVID-19 information for students, albeit being deemed untrustworthy. We recommend that policymakers utilize diverse channels to disseminate health information, ensuring that various demographics receive timely and accurate updates. To combat misinformation, international messengers and social media platforms must implement stringent policies ensuring information quality. This proactive measure is particularly crucial during emergencies, where misinformation could potentially amplify public mortality rates.

5.2. Limitations and Generalizability

The study’s use of convenience sampling may introduce selection bias, despite efforts to diversify the sample across Iranian university virtual groups. The sample, limited to students surveyed from July to November 2020, may not represent those with limited internet access. Exclusion of incomplete questionnaires and reliance on self-reported data could also skew results due to response bias. The findings, based solely on Iranian university students, may not apply to other populations due to differences in cultural contexts, internet access, and crisis experiences. Caution is needed when extending these results beyond the studied cohort.

![Summary of key findings on accessibility vs. trust in COVID-19 information sources: Bars represent percentages of "high" ratings for convenience/accessibility (teal) and trust (orange) from Likert scale responses [data is from <a href="#A157505TBL2">Tables 2</a> and <a href="#A157505TBL5">5</a> (n = 391); multiple responses are allowed; highlights paradox: High convenience (e.g., 61.4% for social media) vs. low trust (5.1%)]. Summary of key findings on accessibility vs. trust in COVID-19 information sources: Bars represent percentages of "high" ratings for convenience/accessibility (teal) and trust (orange) from Likert scale responses [data is from <a href="#A157505TBL2">Tables 2</a> and <a href="#A157505TBL5">5</a> (n = 391); multiple responses are allowed; highlights paradox: High convenience (e.g., 61.4% for social media) vs. low trust (5.1%)].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/5487a1afc76583e6e3cf823a9f6ca48d71c12904/iji-12-1-157505-i001-preview.webp)