1. Background

In December 2019, a new coronavirus strain, SARS-CoV-2, was identified in patients in Wuhan, China. This illness was named coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and became a global pandemic in March 2020. Over 770 million cases and nearly 7.1 million deaths have been reported worldwide (1). Most people experience mild to moderate symptoms, but serious illness is more likely in high-risk groups, including pregnant women and older individuals. Pregnancy causes physiological, immunological, and anatomical changes in the body that can affect how women respond to infections, including COVID-19 (2). A woman’s immune system adjusts to protect the fetus, altering hormone levels such as estrogens and progestins (3). These changes impact immune responses and can increase the risk of respiratory diseases and pneumonia due to decreased respiratory capacity (4). SARS-CoV-2 gains entry into host cells by means of the spike (S) protein binding to its receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which is an enzyme present in several organs, including the intestine, kidney, heart, lungs, and fetal tissues (5). During pregnancy, ACE2 levels rise, increasing the risk of COVID-19 complications for pregnant women (6). The role of ACE2’s enzymatic functions in lung injury related to COVID-19 is still unclear (7). Pregnant women are not at a higher risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2, but if they do, they face a greater chance of severe COVID-19 and preterm birth (8). Research indicates an increased risk of hospitalization and ICU admission of up to 20%, especially in the third trimester (9). Pregnant women with moderate to severe COVID-19 have a heightened risk of adverse outcomes, including cesarean delivery and complications, ICU admission, and maternal mortality (10). Research indicates that existing comorbidities and patient characteristics serve as risk factors for severe and prolonged COVID-19 infections during pregnancy. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of negative maternal and fetal outcomes. Some of the identified risk factors include cardiovascular disease, chronic hypertension, diabetes, kidney failure, chronic lung disease, the use of immunosuppressive medications, advanced maternal age (35 years and older), high Body Mass Index, and non-white ethnicity (11, 12). It has also been suggested that there is a link between preeclampsia and gestational hypertension and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its complications (11). Over three years into the COVID-19 pandemic, much is known about the virus, but its effects on pregnancies and newborns remain unclear (13). COVID-19 complicates pregnancies, posing risks to women’s health and causing financial and psychological strain. A restricted number of studies have examined the effects of COVID-19 on pregnant women in Iran. Additional research into the virus’s influence on this demographic is essential for improved guidance and preventive measures.

2. Objectives

Sistan and Baluchistan province, located in the southeast of Iran, has the highest rate of high-risk pregnancies and maternal deaths in the country, and it hosts a significant proportion of the underprivileged population compared to average national figures. The pre-existing disparity in high-risk pregnancies and maternal mortality rates among the provinces has been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic (14). Therefore, the present study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of adverse outcomes and identify associated predictors among pregnant women with COVID-19 in Zahedan, Iran, during the years 2021 to 2023.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting

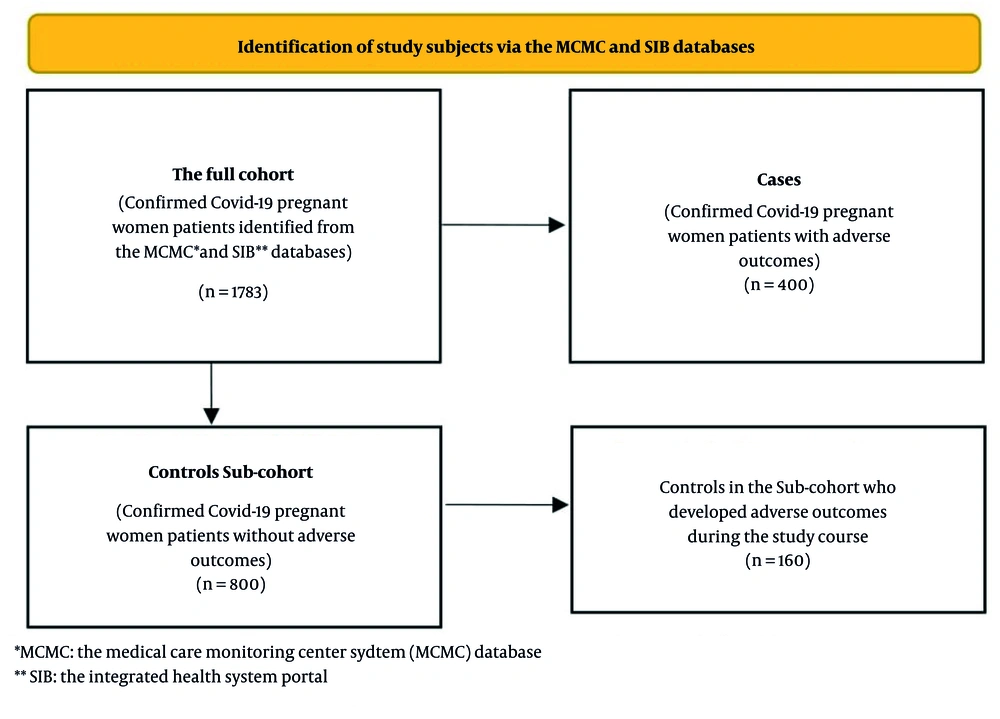

This case-cohort study was conducted between March 2021 and March 2023 in Zahedan, southeast Iran. A case-cohort study classifies participants with a disease as cases and selects controls from the same cohort. This method reduces selection bias and focuses on new cases, helping to clarify associations by examining exposure differences between cases and controls (15). In this study, the full cohort of pregnant women included 1,783 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests. From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Iran’s Ministry of Health set up two web-based databases for registering identified COVID-19 cases in both public and private sectors. Medical Care Monitoring Center (MCMC) database was developed for reporting outpatient and inpatient cases in hospitals, and Integrated Health System (SIB) portal for recording outpatient cases detected by urban and rural health centers (16). This study retrieved data for confirmed COVID-19 cases among pregnant women from the SIB portal and the MCMC database maintained by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. All data concerning pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 were compiled into a unified database for the purposes of this study. Each patient was assigned a distinct identification number. According to the information obtained from the MCMC database, clinical outcomes such as death or hospitalization, along with medical interventions including admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) or the requirement for mechanical ventilation, were classified as patients experiencing adverse outcomes. As presented in Figure 1, a total of 400 confirmed COVID-19 patients with adverse outcomes were identified within the cohort of pregnant women, all of whom were designated as the cases group. Using the SPSS sampling procedure to generate a random sample of patients from the full cohort, a sub-cohort of 800 registered pregnant women who did not experience adverse outcomes at baseline was randomly selected to serve as the control group. From the selected control group, 160 subjects subsequently developed adverse outcomes during the course of the study. No matching was conducted between the cases and controls.

The information regarding maternal deaths was sourced from the database of Iranian Maternal Mortality Surveillance System, maintained by the Vice-Chancellor for Health. This database systematically records and examines all instances of maternal mortality occurring both within and outside hospitals in the regions served by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences.

3.2. Data Collection

A 40-item semi-structured questionnaire was used for collating the data extracted from the SIB portal and the MCMC databases. This questionnaire was developed following an extensive review of the literature and included six sections: Socio-demographic characteristics of the pregnant women (5 questions), medical history encompassing underlying conditions and the use of immunosuppressive drugs (7 questions), obstetric history pertinent to the current pregnancy (4 questions), information regarding COVID-19 vaccination (4 questions), specifics about the COVID-19 illness (11 questions), and COVID-19 disease medical interventions and outcome information, including hospitalization, duration of hospital stay, inpatient ward, mechanical ventilation, and final outcome (9 questions). The information gathered regarding underlying medical conditions included a history of cardiovascular disease, kidney diseases, chronic respiratory disease, and endocrine disorders. The gestational age was determined by recorded database entry. Pregnancy complications were characterized as the existence of pre-existing pregnancy issues (including gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, and pregnancy-induced hypertension) prior to contracting a COVID-19 infection. The vaccination timing during pregnancy was used for data analysis. All individuals who received at least two doses of the vaccine before contracting COVID-19 were considered fully vaccinated.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including counts and percentages, were employed to summarize categorical variables. To estimate excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the P-score was calculated using the following formula:

The expected annual number of deaths was derived from the average number of maternal deaths recorded over the five years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic. The average number of maternal deaths during the study period (between 2021 and 2023) was calculated as the observed annual maternal deaths. Excess mortality was calculated by subtracting the expected number of maternal deaths from the observed mortality. The P-score was reported as the percentage increase in deaths during the study period (17).

The age and gestational age variables contained 44 and 47 missing entries, respectively. The missing values for the age variable were replaced by the mean values from each group. The process of imputing missing data for gestational age was conducted by stratifying subjects according to their trimester of pregnancy group. The median value was calculated for both cases and controls, and this value was utilized to replace the missing data.

The chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test, as applicable, were employed to compare the characteristics of confirmed COVID-19 cases in pregnant women experiencing adverse outcomes compared to those without such outcomes. Additionally, multiple logistic regression models were applied to determine the effective factors linked to adverse outcomes in pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19. All covariates exhibiting a conservative P-value equal to or less than 0.25 in the univariate analyses were entered into the binary multiple logistic regression model. The forward likelihood ratio method was employed to select effective predictors in the final model. The variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis revealed no multicollinearity among the covariates included in the final logistic model. All the interaction terms were forced into a logistic regression model using the Enter method. None of these terms yielded a significant P-value, thus they were omitted from the final model. In light of the study’s design, adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were reported as estimates of relative risk (RR). A P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed significant for all analyses. Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS version 22 statistical software package (Chicago, IL). Approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences on June 17, 2023 (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1402.122).

4. Results

In this study, we used data for a total of 1,783 pregnant women with COVID-19 who were registered in the MCMC and SIB databases. Overall, 400 (22.4%) pregnant women were identified with adverse outcomes and were included in the case group. A sub-cohort of 800 pregnant women was randomly selected as controls. Among pregnant women with adverse outcomes (the cases group), 392 (98.0%) patients were hospitalized, 46 (11.5%) patients were admitted to ICUs, 17 (4.2%) patients required mechanical ventilation, and 34 (8.5%) pregnant women died.

The average annual maternal mortality rate for the five years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic was determined to be 44.2 deaths per 100,000 pregnant women. Throughout the study period, the estimated average annual maternal death rate rose to 48.1 deaths per 100,000 pregnant women, indicating an additional mortality attributed to COVID-19 of 3.9 deaths per 100,000 pregnant women, along with a P-score (annual percent excess mortality) of 8.8%. The socio-demographic characteristics of the cases and controls are presented in Table 1. There were no major age differences between the case and control groups. More cases were in the third trimester. Cases had more underlying diseases and complications. Fewer cases were vaccinated against COVID-19.

| Variables | Cases b | Controls b | P-Value c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (y) | 0.769 | ||

| < 25 | 96 (24.0) | 207 (25.9) | |

| 35 - 25 | 225 (56.2) | 429 (53.6) | |

| > 35 | 79 (19.8) | 164 (20.5) | |

| Gestational age (trimester) | < 0.001 | ||

| First | 24 (6.0) | 129 (16.1) | |

| Second | 51 (12.8) | 189 (23.6) | |

| Third | 325 (81.2) | 482 (60.3) | |

| Underlying disease d | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 96 (24.0) | 123 (15.4) | |

| No | 304 (76.0) | 677 (84.6) | |

| Pregnancy complications e | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 42 (10.5) | 30 (3.8) | |

| No | 358 (89.5) | 770 (96.3) | |

| COVID-19 vaccination | 0.029 | ||

| Yes | 60 (15.0) | 165 (20.6) | |

| No | 340 (85.0) | 635 (79.4) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Percentages represent within-group proportions.

c P-value for chi-square tests.

d Underlying medical conditions: Cardiovascular disease, kidney diseases, chronic respiratory disease, endocrine disorders.

e Pregnancy complications: Gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and pregnancy induced hypertension.

Table 2 compares the clinical manifestations between the cases and the control group. We found that a notably higher percentage of cases experienced shortness of breath, fever, and chills.

| Clinical Manifestation | Cases b | Controls b | P-Value c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coughing/sore throat | 184 (46.0) | 710 (88.8) | < 0.001 |

| Fever and chills | 226 (56.5) | 364 (45.5) | < 0.001 |

| Headache/myalgia | 123 (30.8) | 353 (44.1) | < 0.001 |

| Shortness of breath | 139 (34.8) | 118 (14.8) | < 0.001 |

| Decreased sense of smell/taste | 9 (2.3) | 67 (8.4) | < 0.001 |

| Other symptoms | 76 (19.0) | 216 (27.0) | 0.002 |

| No symptoms | 0 (0.0) | 85 (10.6) | - |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Percentages refer to within-group proportions.

c P-value for chi-square tests.

Multiple logistic regression models were fitted to determine the factors affecting the likelihood of adverse outcomes in pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 (Table 3). The variables gestational age, pregnancy complications, and underlying disease were associated with the risk of adverse outcomes among pregnant women with COVID-19. The chi-square value for the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test was 2.014 with a significance level of 0.847, indicating a good logistic regression model fit.

| Variables | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

| Gestational age (trimester) | ||||||

| First | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Second | 1.4 | 0.8 - 2.4 | 0.170 | 1.33 | 0.7 - 2.2 | 0.289 |

| Third | 3.6 | 2.2 - 5.7 | < 0.001 | 3.2 | 2.0 - 5.1 | < 0.001 |

| Pregnancy complications a | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Yes | 3.0 | 1.8 - 4.8 | < 0.001 | 2.5 | 1.5 - 4.1 | < 0.001 |

| Underlying disease b | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Yes | 1.7 | 1.2 - 2.3 | < 0.001 | 1.6 | 1.2 - 2.2 | < 0.001 |

| COVID-19 vaccination c | ||||||

| No | 0.6 | 04 - 0.9 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.8 - 1.6 | 0.405 |

| Yes | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

a Pregnancy complications: Gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia and pregnancy induced hypertension.

b Underlying medical conditions: Cardiovascular disease, kidney diseases, chronic respiratory disease, endocrine disorders.

c At least two doses of the vaccine administered before contracting COVID-19.

In general, the likelihood of experiencing negative COVID-19 outcomes in women during the third trimester of pregnancy was 3.2 times greater compared to those in the first trimester of pregnancy (AOR = 3.2, 95% CI: 2.0 - 5.1). Women with pregnancy complications were more likely to experience adverse COVID-19 outcomes compared to pregnant women without pregnancy complications (AOR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.5 - 4.1). Similarly, women who had underlying diseases were 1.6 times more likely to have adverse COVID-19 outcomes than those who had no underlying diseases (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.2 - 2.2).

5. Discussion

This case-cohort study found that 22.4% of pregnant women with COVID-19 experienced negative outcomes. Most required hospitalization, with some needing ICU care, mechanical ventilation, or resulting in deaths. Women in their third trimester faced the highest risks. Pregnancy complications and underlying diseases also elevated this risk by 2.5 and 1.6 times, respectively.

Several studies have examined the adverse effects experienced by pregnant women infected with COVID-19. The prevalence of adverse outcomes in our study population was comparable to figures from national studies. However, a notably higher percentage of pregnant women with COVID-19 (8.9%) died from the infection compared to similar studies carried out nationwide. A study of 81 pregnant women with COVID-19 in Yazd, Iran, found that 14.8% needed intensive care and 2.4% required mechanical ventilation, with no fatalities (18). A study of 182 pregnant women with COVID-19 in Iran found that 12% needed ICU care and 6% required ventilation, with no deaths (19). Similarly, a study in Kashan, Iran, found 10.7% of pregnant women with COVID-19 needed ICU care, 14.7% needed ventilation, with no deaths reported (20). A study of 343 pregnant women with COVID-19 in Tehran showed that 82 (23.91%) had severe cases needing ICU care. Fourteen required intubation, and three had tracheostomy (21).

The disparities noted in maternal mortality rates following COVID-19 infection in underprivileged regions, such as the southeast of Iran, can be partially attributed to the socio-cultural environment and unmet healthcare requirements that obstruct the use of available services (14). Additionally, systemic factors within the healthcare framework impede the prompt identification and referral of women with COVID-19, thereby limiting their access to quality healthcare services.

Notably, we observed that women in their third trimester had a 3.26 times greater chance of adverse outcomes compared to those in their first trimester. Our finding is in agreement with results from studies that show higher rates of trimester-specific mortality and adverse outcomes in late pregnancy. A study in Isfahan, Iran, that included data for 430 pregnant women with COVID-19 showed that 74.13% were in the third trimester. More women needed mechanical ventilation in the second trimester, but ICU admissions were similar. Most maternal deaths happened in the third trimester, making up 44.4% of cases (22). A study of 89 pregnant women with COVID-19 in Zanjan, Iran, found an average gestational age of 31.8 weeks and 12.4% needed ICU admission (23). A study of 118 pregnant women with COVID-19 in Oman found that 60.2% were in their third trimester, 9.3% had moderate infections needing hospital care, and 5.1% had severe infections requiring ICU admission (24).

Both COVID-19 and preeclampsia share a common pathological basis: 'Endothelial damage'. Moreover, COVID-19 may heighten the risks for preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome, which accounts for the increased mortality rates observed in pregnant women during the later stages of pregnancy and in the postpartum period (25). Our findings show that pregnant women with underlying diseases like cardiovascular or kidney disease have a 66% higher risk of adverse outcomes from COVID-19 compared to those without these conditions. These results are consistent with findings from other research that has established a correlation between comorbidities and negative outcomes in COVID-19 patients. A sequential, prospective meta-analysis incorporating individual patient data from 21 participating studies revealed that pregnant women with comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease faced a heightened risk for severe COVID-19-related outcomes, maternal morbidities, and negative birth outcomes (26). A study using data from Denmark found that a high Body Mass Index, asthma, and gestational age at infection increased the risk of severe COVID-19 leading to hospital admission. Women with COVID-19 also faced more hypertensive disorders, early pregnancy loss, and preterm deliveries. These effects were stronger in hospitalized women (27). A case-control study in Mexico found that pregnant women with chronic hypertension were 5.12 times more likely to develop severe COVID-19. Other risk factors included non-vaccination and maternal age > 35 years. The case fatality rate was 7.3% (28).

We found that the odds of experiencing adverse outcomes related to COVID-19 were 2.5 times greater in women experiencing pregnancy complications, such as gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and preeclampsia, compared to those without such complications. These findings align with results from other research. For instance, a cohort study from Iran found that the risk of contracting COVID-19 in pregnant women with preeclampsia was 2.68 times that of other women (20). On the contrary, a multicenter international case-control study showed that pregnancy complications did not notably affect severe COVID-19 outcomes in pregnant women (29).

Vaccination stands as the most effective means of safeguarding pregnant women from these recognized risks linked to COVID-19 infection during pregnancy (30). In this study, only 15% of cases and 20% of controls were completely vaccinated. It is crucial to focus on strategic initiatives designed to improve vaccination rates among pregnant women in underserved regions, such as the southeast of Iran, where the incidence of high-risk pregnancies significantly exceeds the national average.

A significant strength of this study lies in the fact that the data analyzed were sourced from national databases specifically created to document information about both inpatient and outpatient COVID-19 patients across public and private sectors. A limitation of this study was the lack of data for some confounding variables, like socioeconomic status and Body Mass Index, which had over 20% missing data. This could lead to residual confounding in the results, which should be interpreted carefully. Moreover, we used MCMC/SIB databases to retrieve the data for pregnant women with COVID-19. An inherent limitation of administrative databases is misclassification bias that can result from diagnostic codes that imperfectly identify pregnant women with COVID-19 among conditions such as severe acute respiratory syndrome, pneumonia unspecified, sepsis, and respiratory failure. Moreover, administrative data may overlook less severe cases that are not documented in MCMC or SIB databases, potentially impacting representativeness. We used imputation methods for dealing with missing data. However, the missing values in this study were trivial (less than 1%) and including the imputed data did not result in significant changes in the distribution of variables. Nevertheless, the findings provide important insights into risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection among pregnant women.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study findings revealed a significant occurrence of adverse effects associated with COVID-19 in pregnant women, especially in those who are in the later stages of pregnancy, those with pre-existing health conditions, and those experiencing complications during pregnancy. Healthcare providers are required to enhance antenatal surveillance by closely monitoring pregnant women diagnosed with COVID-19 for the identified risk factors for adverse outcomes and earlier hospitalization criteria. Targeted vaccination campaigns are also warranted among underprivileged pregnant women.