1. Background

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) encompass a broad spectrum of conditions affecting muscles, bones, joints, tendons, ligaments, and nerves, and represent a major contributor to global disability and healthcare challenges (1). Among these, occupational MSDs are particularly prevalent in diverse populations, including Iranian workers, where meta-analyses have identified high incidence rates and significant associated risk factors such as repetitive strain, poor ergonomics, and socioeconomic determinants (2, 3). Beyond occupational exposures, early life factors, particularly motor development and physical activity patterns, are increasingly recognized as foundational in shaping long-term musculoskeletal health trajectories.

Infancy is a critical period in which motor milestones and neuromuscular control develop rapidly, laying the groundwork for physical function and posture across the lifespan. To support this process, caregivers frequently employ various mobility aids, with baby walkers (BWs) being a common choice due to their perceived benefits in accelerating walking acquisition and providing entertainment (4). However, despite their popularity, growing evidence signals potential adverse effects associated with frequent BW use, including disruptions in neuromotor development, postural adaptations, and decreased overall physical activity levels (5). These concerns are underscored by the absence of standardized guidelines or consensus on the safe and effective use of BWs during infancy, creating a clinical and public health gap.

While prior studies have mainly examined the influence of BW use on gross motor milestones and gait abnormalities (6, 7), less attention has been devoted to its impact on posture and habitual physical activity, key components of musculoskeletal health and neuromotor function. Moreover, given the broader context of rising global MSD burden and regional disparities influenced by socioeconomic and environmental factors (1-3), there is a pressing need to comprehensively evaluate how early use of mobility aids like BWs may contribute to musculoskeletal development or dysfunction.

2. Objectives

This study aims to address these gaps by investigating differences in physical activity levels, muscle strength, and postural control between children who used walkers during infancy and those who did not. By elucidating these relationships, the findings seek to inform caregivers, clinicians, and policymakers to guide safer infant mobility practices and support optimal musculoskeletal and neuromotor outcomes in early childhood.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional study conducted with 39 children aged 8 - 14 years, admitted to the Pediatrics Clinic of Mustafa Kemal University Faculty of Medicine Hospital. Volunteer children, without idiopathic or severe orthopedic problems or chronic diseases, along with their parents, were included in the study. Children with neurological and neuromuscular diseases or mental retardation were excluded. Prior to the study, informed consent was obtained from both the parents and children who agreed to participate.

The children were divided into two groups: Those who used a BW (the "Walker Users" group) and those who did not (the "Non-Walker Users" group). The study was approved by the Hatay Mustafa Kemal University Tayfur Ata Sokmen Medical Faculty Clinical Research Ethics Committee, with protocol number 2021/177.

3.2. Outcome Measures

The study collected demographic information from the participants, including gender, age, body weight, height, and Body Mass Index, using a form developed by the authors. Additionally, parents were asked about the children's stages of motor development, the use of a BW, the age at which the walker was first used, and the duration of its use. Children's muscle strength was measured using a digital muscle strength meter. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children was used to assess the physical activity levels of all participants. Finally, the New York Posture Analysis Questionnaire was employed to evaluate the children's posture.

3.2.1. Digital Muscle Strength Meter

Our study objectively measured muscle strength using the JTech Commander PowerTrack Muscle Dynamometer.

3.2.1.1. Right and Left Muscle Tests

The hip flexors/extensors/adductors /abductors/internal rotators/ external rotators , knee flexors/extensors, and foot plantar flexors/dorsiflexors were evaluated. The measurement results were recorded in Newton (N). The measurements were repeated three times, and the average of these three repetitions was recorded.

3.2.2. International Physical Activity Scale for Children

The International Physical Activity Scale for Children (IPAQ-C) was used to evaluate physical activity levels in children aged 4 - 14 over the past 7 days. It consists of nine items scored on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates low and 5 indicates high physical activity. A mean score was calculated by dividing the total score by the number of items (8, 9). The Turkish version of the questionnaire, proven valid and reliable (10), was administered under supervision. Standardized instructions were provided, and children completed the form independently. Higher scores reflect greater physical activity levels.

3.2.3. New York Posture Rating

Posture was assessed using the New York Posture Rating (NYPR), which evaluates 13 body segments from lateral and posterior views (11). Each segment was scored as: 5: Normal alignment; 3: Moderate deviation; 1: Severe deviation. The total score ranges from 13 to 65, with lower scores indicating poorer posture. Children stood barefoot in neutral posture, and assessments were performed by a trained physiotherapist using a standardized observation distance and form.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 25) statistical program, and descriptive values were determined as mean, standard deviation, and percentage. The suitability of the data for normal distribution was evaluated by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The “Mann-Whitney U” test method was used to compare two independent groups for quantitative measurement values that did not conform to normal distribution. The Wilcoxon test was used to determine the statistical difference between two non-parametric matched groups. The significance level was accepted as P < 0.05 in all tests.

4. Results

The demographic and anthropometric characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The walker users group consisted of 10 girls (41.7%) and 14 boys (58.3%), while the non-walker users group included 5 girls (33.3%) and 10 boys (66.7%).

| Variables | Walker Users Group | Non-walker Users Group |

|---|---|---|

| Girl/boy | 10/14 (41.7/58.3) | 5/10 (33.3/66.7) |

| Age (y) | 10.83 ± 1.65 | 10.13 ± 1.88 |

| Height (cm) | 147.25 ± 15.50 | 135.00 ± 13.41 |

| Body weight (kg) | 43.02 ± 15.33 | 31.13 ± 9.51 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 19.27 ± 4.15 | 16.82 ± 2.26 |

Abbreviations: cm, centimeter; kg, kilogram; m2, square meter.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The mean age of children in the walker users group was 10.83 ± 1.65 years, whereas it was 10.13 ± 1.88 years in the non-walker users group. The average height was higher in the walker users group (147.25 ± 15.50 cm) compared to the non-walker users group (135.00 ± 13.41 cm).

Similarly, the mean body weight was greater among walker users (43.02 ± 15.33 kg) than non-walker users (31.13 ± 9.51 kg). Body Mass Index was also higher in the walker users group (19.27 ± 4.15 kg/m2) compared to the non-walker users group (16.82 ± 2.26 kg/m2).

The comparison of motor development stages between walker users and non-walker users is presented in Table 2.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Mann-Whitney U test.

c Significant P < 0.05.

According to the results the mean age for head holding was 3.20 ± 1.10 months in the walker users group and 2.73 ± 0.59 months in the non-walker users group, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (P = 0.208). Moreover, the mean age for achieving unsupported sitting was significantly higher in the walker users group (6.29 ± 1.23 months) compared to the non-walker users group (5.33 ± 1.04 months), and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.022). For crawling independently, the walker users had a mean age of 7.50 ± 1.61 months, while non-walker users had a mean of 7.33 ± 1.63 months; no significant difference was found (P = 0.546). Additionally, the mean age for walking was 12.33 ± 2.38 months in the walker users group and 13.20 ± 3.80 months in the non-walker users group, which was also not statistically significant (P = 0.683).

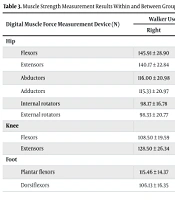

In the intragroup muscle strength analysis of the children included in this study, the mean right hip extensor muscle strength was significantly higher than the mean left hip extensor muscle strength in the walker users group (P = 0.024). In the non-walker users group, the mean right hip abductor muscle strength was significantly greater than the mean left hip abductor muscle strength (P = 0.019), and the mean right foot dorsiflexor muscle strength was significantly higher than the mean left foot dorsiflexor muscle strength (P = 0.036).

Intergroup analysis revealed that the mean left hip abductor muscle strength (P = 0.014), mean right hip adductor muscle strength (P = 0.008), mean right and left foot dorsiflexor muscle strengths (P = 0.033 and P = 0.001, respectively), and the mean right foot plantar flexor muscle strength (P = 0.021) were significantly higher in children in the walker users group compared to those in the non-walker users group (Table 3).

| Digital Muscle Force Measurement Device (N) | Walker Users Group | P-Value b | Non-walker Users Group | P-Value b | P-Value c (Right/Left) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Right | Left | ||||

| Hip | |||||||

| Flexors | 145.91 ± 28.90 | 141.17 ± 28.09 | 0.071 | 154.13 ± 41.97 | 147.47 ± 42.73 | 0.151 | 0.633/0.885 |

| Extensors | 140.17 ± 22.84 | 130.21 ± 27.24 | 0.024 d | 129.33 ± 28.86 | 128.33 ± 32.04 | 0.875 | 0.312/0.675 |

| Abductors | 116.00 ± 20.98 | 115.33 ± 20.02 | 0.732 | 106.13 ± 20.87 | 96.67 ± 19.46 | 0.019 d | 0.296/0.014 d |

| Adductors | 115.33 ± 20.97 | 109.38 ± 19.08 | 0.140 | 94.40 ± 20.05 | 101.47 ± 22.54 | 0.119 | 0.008 d/0.592 |

| Internal rotators | 98.17 ± 16.78 | 99.92 ± 18.50 | 0.871 | 82.33 ± 25.63 | 79.60 ± 26.77 | 0.348 | 0.053/0.075 |

| External rotators | 98.33 ± 20.77 | 96.04 ± 19.62 | 0.287 | 81.60 ± 30.74 | 79.07 ± 25.22 | 0.530 | 0.102/0.092 |

| Knee | |||||||

| Flexors | 108.50 ± 19.59 | 103.96 ± 20.18 | 0.067 | 95.60 ± 23.77 | 99.47 ± 25.50 | 0.148 | 0.160/0.862 |

| Extensors | 128.50 ± 26.34 | 123.50 ± 23.34 | 0.091 | 127.20 ± 29.41 | 121.00 ± 26.23 | 0.093 | 0.784/0.318 |

| Foot | |||||||

| Plantar flexors | 115.46 ± 14.37 | 110.67 ± 14.14 | 0.064 | 101.67 ± 18.06 | 101.53 ± 22.96 | 0.814 | 0.021 d/0.187 |

| Dorsiflexors | 106.13 ± 16.35 | 102.96 ± 15.16 | 0.360 | 88.40 ± 22.69 | 80.80 ± 19.49 | 0.036 d | 0.033 d/0.001 d |

Abbreviation: N, Newton.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Wilcoxon test.

c Mann-Whitney U test.

d Significant P < 0.05.

No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of posture analysis results and overall physical activity levels (excluding weekends) (P = 0.581 and P = 0.762). However, the mean weekend activity level was significantly higher in the non-walker users group (3.53 ± 1.19) compared to the walker users group (2.54 ± 0.98). Intergroup analysis demonstrated that children in the non-walker users group had significantly greater physical activity levels on weekends than those in the walker users group (P = 0.008; Table 4).

| Variables | Walker Users Group | Non-walker Users Group | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPAQ-C parameters | |||

| Leisure activity checklist | 25.83 ± 3.82 | 25.80 ± 6.20 | 0.919 |

| Physical education | 4.04 ± 1.04 | 3.60 ± 1.54 | 0.455 |

| Respiration | 2.92 ± 1.25 | 3.40 ± 1.59 | 0.203 |

| Lunch | 2.25 ± 1.22 | 2.06 ± 1.53 | 0.499 |

| After school | 3.08 ± 1.35 | 3.33 ± 1.63 | 0.622 |

| Evenings | 2.29 ± 1.37 | 3.26 ± 1.66 | 0.079 |

| Weekend | 2.54 ± 0.98 | 3.53 ± 1.18 | 0.008 c |

| What defines you best | 2.96 ± 1.08 | 2.73 ± 1.33 | 0.539 |

| Activity frequency for each day of the past week | 21.92 ± 5.06 | 21.53 ± 7.45 | 0.977 |

| IPAQ total score | 67.58 ± 12.06 | 69.26 ± 19.11 | 0.762 |

| NYPR | 52.63 ± 6.82 | 53.80 ± 6.09 | 0.581 |

Abbreviations: IPAQ-C, International Physical Activity Scale for Children; NYPR, New York Posture Rating.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Mann-Whitney U test.

c Significant P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the differences in physical activity and functioning between children who used a walker and those who did not during infancy. The results revealed a significant difference between the IPAQ-C weekend item parameters and the muscle strength of the left hip abductor muscles, right hip adductor muscles, right foot plantar flexor muscles, and both lower extremity dorsiflexor muscles. A review of the literature reveals a plethora of studies investigating the impact of BWs on motor development. However, the findings are often contradictory (5-7). While some researchers argue that BWs affect motor development, others contend there is no effect, and some evidence suggests a negative impact (5-7, 12, 13).

In this study, independent walking occurred on average one month earlier in the walker-using group. However, no significant difference was found between the groups in motor development stages, except for the month of sitting without support. Muscle strength of the right hip adductors, right foot plantar flexors, and bilateral dorsiflexors was significantly different in children who used walkers compared to non-users. These differences may reflect asymmetrical musculoskeletal development similar to patterns described in previous studies on physical imbalance and joint loading in children (14). The muscle strength development in walker users may have been influenced by factors such as engagement in sports or other environmental variables. To ensure objectivity, future studies should analyze these factors. Additionally, significant differences were observed between limbs within both groups.

Walker use allows observation of postures and movements not typically seen in normal independent walking (7), including abnormal trunk flexion and increased plantar flexion. In this study, the rectus femoris muscle showed more muscle action potentials but less activation during walking in the walker group. It is hypothesized that since the infant’s weight is supported by the walker, muscle contraction needed for posture may be reduced, facilitating anti-gravity development. Furthermore, walker users exhibited more lateral movements, possibly due to increased hip amplitude in the sagittal plane (7). These postural adaptations may contribute to idiopathic toe walking by negatively affecting normal walking patterns and posture development in early childhood (15). Although walker use might cause short-term gait and posture disorders, these may be tolerated during the child’s postural maturation.

Changes in posture and body kinematics can affect physical activity (16, 17). Ergonomic environmental factors, such as poor support surfaces or non-adaptive equipment, also influence children's postural habits and musculoskeletal health (18). However, literature on BW use and physical activity remains limited.

The findings must be contextualized within the global burden of MSD. The global burden of disease (GBD) study 2021 reports a rising prevalence projected through 2050 (1), highlighting the critical need for early interventions to optimize musculoskeletal development and prevent long-term impairments. Infant mobility aids like BWs require careful evaluation due to their potential to adversely affect development. Regional and socioeconomic disparities in musculoskeletal health emphasize the necessity for tailored public health strategies and clinical guidelines. Our results reinforce the importance of educating caregivers and health professionals about the limited benefits and potential risks of BW use, especially in regions where regulation is lacking.

Raei et al.'s systematic review highlights that MSDs arise from complex interactions among biomechanical stresses, repetitive movements, and environmental factors (3). Though focused on adults, these risk factors, such as prolonged mechanical loading and ergonomic strain, underscore the importance of early musculoskeletal health and posture. Our findings of muscle asymmetries and altered posture in walker users suggest inappropriate biomechanical loading during critical periods may predispose to long-term imbalances, emphasizing the need for early prevention and caregiver education.

Recent occupational health ergonomics research stresses that early postural habits and biomechanical stresses influence MSD risk later in life (19). Ergonomic education focused on posture and movement from infancy is essential for promoting lifelong musculoskeletal health. Devices like BWs, which may promote maladaptive postures and asymmetrical loading, should be critically assessed. Incorporating ergonomic principles into caregiver education and encouraging safe, floor-based activities that support natural movement and muscle development are recommended.

The MSDs are also a significant global occupational health concern. Parno et al.'s meta-analysis on Iranian workers found a high prevalence of occupational MSDs (2). This epidemiological evidence extends the importance of musculoskeletal health beyond childhood, suggesting that early development, influenced by devices like BWs, may have lifelong consequences. This underscores the urgency of identifying and modifying early risk factors to reduce the lifetime burden of MSDs.

To mitigate risks, evidence-based strategies include integrating walker use counseling into pediatric care, providing safe alternatives to caregivers, and promoting public health awareness campaigns. Regulatory policies such as product labeling and age restrictions, successful in some countries, should be promoted globally.

While this study focused on walker use, confounding factors such as physical activity levels, lifestyle habits, environmental conditions, and socioeconomic status also influence motor development (20). The lower weekend physical activity observed in walker users may reflect broader lifestyle and socioeconomic factors. Future research should aim to isolate these variables and analyze their interaction with mobility aid use for a comprehensive understanding of child development.

5.1. Conclusions

A considerable number of families continue to use BWs, driven by the belief that these devices facilitate early mobility. However, our findings did not reveal significant differences between the groups in terms of motor development stages, except for the earlier onset of independent sitting in children who did not use walkers. Although differences in posture and muscle strength were observed, these did not reach statistical significance across all parameters, highlighting the complexity of establishing long-term musculoskeletal outcomes based on early-life mobility aids. These results emphasize the need for longitudinal studies to track developmental trajectories from childhood to adulthood and to perform repeated evaluations at shorter follow-up intervals in order to better understand the potential long-term effects of BW use.

5.2. Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small and limited to a single hospital, so future multicenter studies with larger and more diverse populations are needed. Second, the long interval since walker use may cause recall bias. However, walker use is a memorable event for parents, and we only included those with clear recollections. Despite the retrospective design, we applied objective musculoskeletal and physical activity assessments. Lastly, the cross-sectional design prevents causal conclusions. Future longitudinal studies considering confounding factors like socioeconomic status and gait analysis are recommended to better understand the impact of early walker use.