1. Background

Isohemagglutinins, developed against ABO blood group antigens, play a crucial role in transfusion and transplantation medicine. In recent years, there has been an increase in transplant procedures involving blood group-incompatible donors in both solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). This surge is due, in part, to the shortage of donors relative to the number of patients awaiting transplants and the challenges associated with finding a suitable donor for each patient. Consequently, the use of various stem cell sources for HSCT and the concept of cross-donors for solid organ transplantation are gaining prominence (1, 2). ABO-incompatible kidney and liver transplants are much more common than heart transplants, reflecting varying body responses to different organs. In the early stages of life, including the neonatal and infancy periods, the immune system is not fully developed and antibody production is minimal. Consequently, ABO-incompatible heart transplants are often favored during these stages, with their numbers increasing globally (3-6). Today, ABO-incompatible stem cell transplantations account for 30 - 40% of all allogeneic transplantations. Of these, 20 - 25% are classified as major incompatible, 20 - 25% as minor incompatible, and the remainder as bidirectional incompatible transplants (7, 8).

Complications arising from these transplantations have the potential to increase transplant-related mortality. For instance, recipient isohemagglutinins may present problems in major incompatible transplants. Similarly, complications in minor incompatible transplants can originate from passive isohemagglutinins in the donated product. Issues can range from early or late immunohemolytic transfusion reactions to delayed erythrocyte engraftment or pure erythroid aplasia (9). Throughout the HSCT process, both donor and recipient cells, along with isohemagglutinins, circulate in the patient’s bloodstream until engraftment. However, owing to the chaotic nature of the microenvironment during this period, it is not possible to determine the patient’s blood type, necessitating the administration of blood transfusions by specialized personnel. Despite these complexities, the standard transfusion principles currently utilized for hemato-oncology patients are similarly applied to those undergoing transplantation (10, 11).

2. Objectives

Any healthy individual who donates blood could potentially serve as a transfusion donor for recipients of an ABO-incompatible allogeneic stem cell transplant. The present study aimed to underscore the significance of knowing isohemagglutinin titers to ensure safe transfusion practices during transplant operations. Undertaken in Istanbul, a cosmopolitan city, at the ‘Istanbul Medical Faculty Blood Center’, this work is significant because of the high volume of blood donors (over 40,000 annually) at the center. Consequently, it offers a large sample size for analyzing isohemagglutinin titers in donors.

3. Methods

We examined the frequency of blood groups and their distribution by sex and decade among volunteer donors at the Istanbul Medical Faculty Blood Center over 1 month, between February 1 and March 15, 2014. We randomly selected individuals with blood groups A, B, and O, and evaluated their isohemagglutinin titers. All donors met the following inclusion criteria: Age, 18 - 60 years; hemoglobin levels ≥ 12.5 g/dL; no history of transfusion in the past 12 months; and absence of chronic illness. Their transfusion-transmitted infection status was nonreactive and negative for red blood cell alloantibodies.

We used the column agglutination method (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, UK) to determine isohemagglutinin titers, specifically anti-B IgM and IgG for blood group A, anti-A IgM and IgG for blood group B, and both anti-A IgM and IgG and anti-B IgM and IgG for blood group O. The distribution of these titers according to sex was also examined.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Number Cruncher Statistical System (NCSS) 2007 program from Kaysville, Utah, USA. Quantitative data were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test in two group comparisons of parameters that were not exhibited using normal distribution and descriptive statistical methods (frequency, ratio, minimum, maximum, and median). Yates’ continuity adjustment test (chi-square with Yates adjustment) and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the qualitative data. Statistical significance was assessed at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01. No adjustment for confounders was conducted, owing to the predominantly descriptive characteristics of the study. All the outcomes were unmodified. Comparisons were made between male and female donors across each blood group. No formal subgroup or interaction analysis was performed. The participants were randomly selected using stratified sampling by ABO blood group. No imputation approach was utilized for the absence of data, owing to the completeness of the dataset.

This study had a cross-sectional design, and longitudinal designs are advisable for future research to evaluate temporal fluctuations in isohemagglutinin titers. This study evaluated isohemagglutinin (anti-A and anti-B IgM/IgG) titers in 1005 selected individuals (335 from the A blood group, 335 from the B blood group, and 335 from the O blood group). These individuals were among the 3708 healthy blood donors who met the standard donor conditions. With 1005 participants and a strong male-to-female sample ratio, this study achieved over 92% statistical power to detect moderate gender-related differences in isohemagglutinin titers at α = 0.05. The evaluation considered the distribution of titers based on gender and age, the detectability of the critical isohemagglutinin titer value, and the frequency of these titers in relation to blood groups within our community.

The study was approved by Istanbul Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee on March 7, 2014 (file no: 2014/464). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

3.1. Sources of Bias

The donor pool had a sex imbalance (95.2% male), and no adjustments were made for potential confounders such as pregnancy history, vaccination status, or previous transfusion history.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Flow

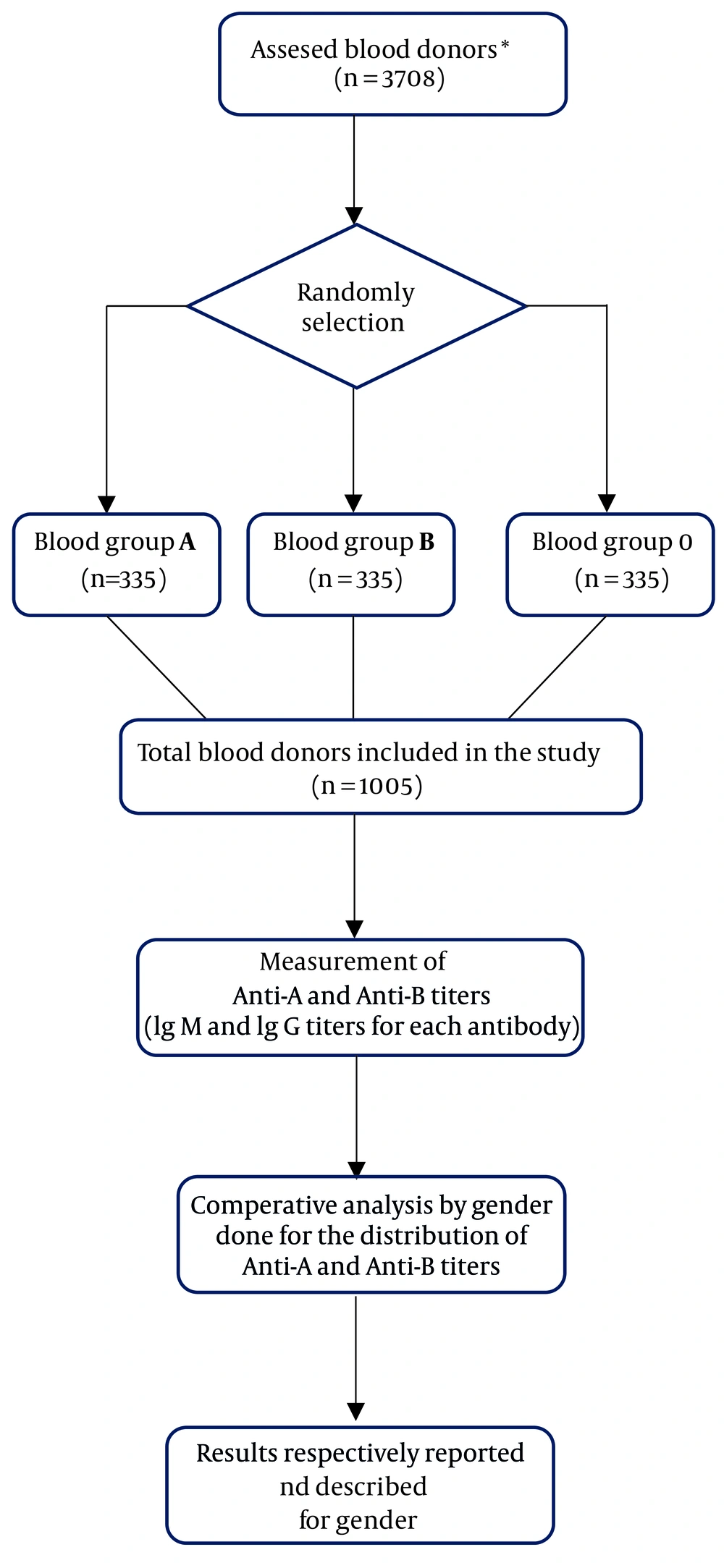

A total of 3708 blood donors were evaluated for eligibility. Among these, 1005 were randomly selected for inclusion in the study and stratified by the ABO blood group. All comparisons represented unadjusted analyses, and no control for confounding variables was applied. All selected donors met the inclusion criteria. The distribution and analysis steps of the study population are presented in the “Participant Flow Diagram” (Figure 1).

The study involved 1005 participants (957 males and 48 females) aged 18 to 59 years, with an average age of 33.96 ± 8.86 years. Among these, 40.3% (405 individuals) were aged between 26 - 35 years. A breakdown by blood type revealed that males predominated in each group: 324 (96.7%) had blood type A, 314 (93.7%) had type B, and 319 (95.2%) had type O.

The two most frequently observed titer values for anti-A IgM in the given blood group were 1:32 and 1:64 in the O group. For anti-A IgG, the common titer values were 1:512 and 1:256. Similarly, for anti-B IgM, the two most common titers were 1:32 and 1:16, respectively. The three most frequent titer values for anti-B IgG in the O group were 1:256, 1:512, and 1:128. In blood group A, the most common titers for anti-B IgM were 1:8, 1:16, and 1:4. The most frequently observed titers for anti-B IgG were 1:32, 1:64, and 1:16.

When considering sex in the evaluation of isohemagglutinin ratios in blood groups, the three most common anti-A IgM titers for female patients in blood group B were 1:8, 1:16, and 1:32, with a median value of 1:16. When assessing the most common anti-A IgG titers, we found an equal number of cases with titers of 1:64, 1:128, and 1:256 (Table 1). The anti-B IgM titer values in male subjects in group A varied from 1:2 to 1:128, with a median of 1:8. For female participants, this variation was between 1:2 and 1:32, with a median of 1:8. Sex did not significantly influence anti-B IgM titers in subjects in blood group A (P = 0.847, P > 0.05). However, the median anti-B IgM titer was the same (1:8) in both males and females (Table 2).

| Blood Groups and Titer | Total | Male | Female | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | ||||

| Anti-A IgM | 10.123 a | |||

| 1:1 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:2 | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:4 | 7 (2.1) | 6 (1.9) | 1 (6.3) | |

| 1:8 | 25 (7.5) | 25 (7.8) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:16 | 49 (14.6) | 47 (14.7) | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:32 | 95 (28.4) b | 91 (28.5) b | 4 (25.0) b | |

| 1:64 | 90 (26.9) b | 87 (27.3) b | 3 (18.8) b | |

| 1:128 | 51 (15.2) | 49 (15.4) b | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:256 | 12 (3.6) | 8 (2.5) | 4 (25.0) b | |

| 1:512 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (range) | 1:32 (1:4 - 1:256) | 1:64 (1:1 - 1:51) | ||

| Anti-A IgG | 10.163 a | |||

| 1:2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:8 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:16 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:32 | 4 (1,2) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:64 | 22 (6.6) | 21 (6.6) | 1 (0.3) | |

| 1:128 | 46 (13.7) | 45 (14.1) | 1 (0.3) | |

| 1:256 | 87 (26.0) b | 82 (25.7) b | 5 (31.3) | |

| 1:512 | 121 (36.1) b | 118 (37.0) b | 3 (18.8) | |

| 1:1024 | 50 (14.9) | 45 (14.1) | 5 (31.3) | |

| 1:2048 | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Median (range) | 1:512 (1:8 - 1:2048) | 1:512 (1:64 - 1:2048) | ||

| B | ||||

| Anti-A IgM | 10.122 a | |||

| 1:1 | 11 (3.3) | 11 (3.5) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:2 | 29 (8.7) | 27 (8.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| 1:4 | 65 (19.4) b | 63 (20.1) b | 2 (9.5) | |

| 1:8 | 90 (26.9) b | 84 (26.8) b | 6 (28.6) b | |

| 1:16 | 85 (25.4) b | 80 (25.5) b | 5 (23.8) b | |

| 1:32 | 37 (11.0) | 34 (10.8) | 3 (14.3) b | |

| 1:64 | 13 (3.9) | 12 (3.8) | 1 (4.8) | |

| 1:128 | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| 1:256 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (range) | 1:8 (1:1 - 1:256) | 1:16 (1:2 - 1:128) | ||

| Anti-A IgG | 10.085 b | |||

| 1:2 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:4 | 10 (3.0) | 10 (3.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:8 | 13 (3.9) | 13 (4.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:16 | 38 (11.3) | 35 (11.1) | 3 (14.3) | |

| 1:32 | 69 (20.6) b | 67 (21.3) b | 2 (9.5) | |

| 1:64 | 71 (21.2) b | 66 (21.0) b | 5 (23.8) | |

| 1:128 | 82 (24.5) b | 77 (24.5) b | 5 (23.8) | |

| 1:256 | 42 (12.5) | 37 (11.8) | 5 (23.8) | |

| 1:512 | 5 (1.5) | 4 (1.3) | 1 (4.8) | |

| 1:1024 | 3 (0.9) | 3 (1,0) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (range) | 1:64 (1:2 - 1:1024) | 1:128 (1:16 - 1:512) |

a Mann-Whitney U test.

b The first three most frequently detected titers in volunteer blood donors with blood group B and the first two most frequently detected titers in volunteer blood donors with blood group O.

| Blood Groups and Titer | Total | Male | Female | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | ||||

| Anti-B IgM | 0.001 a, b | |||

| 1:2 | 7 (2.1) | 7 (2.2) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:4 | 10 (3.0) | 10 (3.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:8 | 46 (13.7) | 46 (14.4) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:16 | 64 (19.1) c | 63 (19.7) c | 1 (6.3) | |

| 1:32 | 121 (36.1) c | 114 (35.7) c | 7 (43.8) c | |

| 1:64 | 55 (16.4) | 53 (16.6) c | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:128 | 26 (7.8) | 22 (6.9) | 4 (25.0) c | |

| 1:256 | 4 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:512 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (range) | 1:32 (1:2 - 1:512) | 1:128 (1:16 - 1:256) | ||

| Anti-B IgG | 0.017a, b | |||

| 1:2 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:8 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:16 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:32 | 15 (4.5) | 15 (4.7) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:64 | 32 (9.6) | 30 (9.4) | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:128 | 74 (22.1) c | 72 (22.6) c | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:256 | 93 (27.8) c | 91 (28.5) c | 2 (12.5) | |

| 1:512 | 89 (26.6) c | 85 (26.6) c | 4 (25.0) c | |

| 1:1024 | 27 (8.1) | 22 (6.9) | 5 (31.3) c | |

| 1:2048 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (6.3) | |

| Median (range) | 1:256 (1:8 - 1:2048) | 1:512 (1:64 - 1:2048) | ||

| A | ||||

| Anti-B IgM | 0.847 a | |||

| 1:2 | 51 (15.2) | 49 (15.1) | 2 (18.2) | |

| 1:4 | 61 (18.2) c | 61 (18.2) c | 0 (0) | |

| 1:8 | 90 (26.9) c | 85 (26.2) c | 5 (45.5) c | |

| 1:16 | 73 (21.8) c | 71 (21.9) c | 2 (18.2) | |

| 1:32 | 39 (11.6) | 37 (11.4) | 2 (18.2) | |

| 1:64 | 18 (5.4) | 18 (5.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:128 | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (range) | 1:8 (1:2 - 1:128) | 1:8 (1:2 - 1:32) | ||

| Anti-B IgG | 0.586 a | |||

| 1:2 | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (9.1) | |

| 1:4 | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:8 | 26 (7.8) | 25 (7.7) | 1 (9.1) | |

| 1:16 | 58 (17.3) c | 57 (17.6) c | 1 (9.1) | |

| 1:32 | 80 (23.9) c | 77 (23.8) c | 3 (27.3) | |

| 1:64 | 76 (22.7) c | 73 (22,5) c | 3 (S27.3) | |

| 1:128 | 54 (16.1) | 53 (16.4) | 1 (9.1) | |

| 1:256 | 31 (9.3) | 30 (9.3) | 1 (9.1) | |

| 1:512 | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1:1024 | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Median (range) | 1:32 (1:2 - 1:1024) | 1:32 (1:2 - 1:256) |

a Mann-Whitney U test.

b P < 0.05.

c The first three most frequently detected titers in volunteer blood donors with blood group A and the first two most frequently detected titers in terms of Anti-B Ig M and the first three most frequently detected titers in terms of Anti-B Ig G in volunteer blood donors with blood group O.

The anti-B IgG titers in male subjects with blood group A ranged from 1:2 to 1:1024, whereas in female subjects, the range was 1:2 to 1:256. The median titer value for both genders was 1:32. Based on this observation, no statistically significant difference was found between the anti-B IgG titers in blood group A according to sex (P = 0.586; P > 0.05) (Table 2). However, among subjects with blood group O, female subjects demonstrated significantly higher anti-B IgM titers than male subjects (P = 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Table 2).

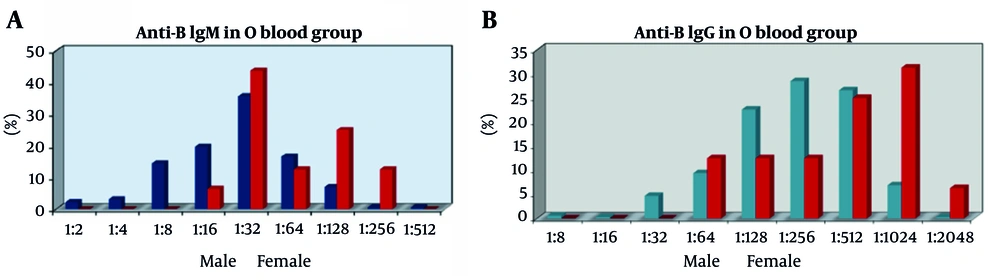

The anti-A IgG titers in male individuals with blood group O ranged from 1:8 to 1:2048. For females, titers varied from 1:64 to 1:2048. The median anti-A IgG titer for both sexes was 1:512. Furthermore, no significant statistical difference was identified in the anti-A IgG titers of patients in the O blood group across the sexes (P = 0.163; P > 0.05) (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in anti-B IgM titers of the O blood group, with ranges of 1:2 to 1:64 and 1:512, observed between the sexes (P > 0.05). However, it was found to be statistically significant that titers of 1:128 and 1:256 were higher in women than in men (P = 0.027, P = 0.012, P < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 2A).

There were no significant sex-based differences in the anti-B IgG titers of 1:8, 1:16, 1:32, 1:64, 1:128, 1:256, 1:512, and 1:2048 among the O blood group donors (P > 0.05). However, a notable exception was found in the 1:1024 titer ratio, where women exhibited higher levels than men. This finding was statistically significant (P = 0.005 and P < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 2B). Lastly, anti-A IgM titers of 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:8, 1:16, 1:32, 1:64, 1:128, and 1:512 O blood group donors in the study were evaluated based on sex. No statistically significant differences were observed (P > 0.05) (Figure 2B). Nonetheless, the 1:256 titer ratio was significantly higher in women than in men (P = 0.001 and P < 0.01, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference in anti-A IgG titers between the sexes (P > 0.05).

5. Discussion

The distribution and frequency of ABO blood groups are not uniform across countries. The O blood group, comprising 46.7% of the population, is the most prevalent in the United States. In addition, 85.4% of all donors were Rh D-positive [RhD (+)], with the remaining 14.6% being Rh D-negative [RhD (-)] (12). The A blood group is notably more common in Northern and Central European nations, such as those in Scandinavia (13). A high frequency of O and A blood groups was observed in Australia, mirroring the pattern in Central Europe. Conversely, Africa has a larger number of individuals in the B blood group (14-16). In 2012, Kayıran et al. found that among 4,656 newborns in Istanbul, the most prevalent blood type was A Rh D (+) and AB Rh D (−) was the least common (17). Yuksel Salduz et al.’s study analyzed data from 6,041 healthy blood donors, revealing that blood groups A, O, B, and AB are represented at frequencies of 43.44%, 33.02%, 15%, and 8.54%, respectively. Additionally, these researchers reported that 85.95% (n = 5192) of the donors were Rh D (+) and 14.05% (n = 849) were Rh D (-). Furthermore, they observed that most blood donors were male (92.42%) and aged 25 - 44 years (69.28%). They concluded that the distribution of ABO and Rh blood groups in Istanbul reflects the general rates in Turkey (18).

In our study, the distribution of ABO blood groups was as follows: RhD (+) 34.9%; RhD (-) 5.45%; B RhD (+) 13.98%; B RhD (-) 2.49%; AB RhD (+) 9.47%; AB RhD (-) 0.89%; O Rh D (+) 27.51%; and O RhD (-) 5.47%. Additionally, the blood group distribution among the 1005 individuals randomly selected from 3708 blood bank donors for our isohemagglutinin study during the specified period was similar, with blood group A at 41%, blood group B at 16%, and blood group O at 33%. In an extensive study conducted at Istanbul Medical Faculty Blood Center, which examined data from 136,231 donors between January 2014 and December 2019, blood group A was identified as the most prevalent, occurring in 41.88% (n = 57,059) of donors, followed by group O at 34.92% (n = 47,576), group B at 15.26% (n = 20,790), and group AB at 7.93% (n = 10,806). Moreover, 85.02% of the donors were identified as RhD (+) (19).

Based on these findings, the distribution of blood groups among healthy donors in our study was largely consistent with both the six-year study conducted at our own blood center (19) and the data reported by Yuksel Salduz et al. (18), particularly in terms of blood groups B and O. However, our study identified a slightly higher frequency of blood group AB and a marginally lower frequency of blood group A. In our study of 1005 voluntary blood donors, 95.2% were male and merely 4.8% (n = 48) were female, aligning with results from earlier blood donation research in Turkey (17-19). Comparably low female participation rates have been documented in various isohemagglutinin titer investigations from Asia (2.74% - 14.3%) (20-26), although elevated rates were noted in Africa (27, 28) and Brazil (34.3%) (29). The absence of female donors may be partially attributed to the significant incidence of iron deficiency anemia among women of reproductive age, along with cultural and socioeconomic variables that affect voluntary blood donation.

Prior research indicates that females may demonstrate elevated isohemagglutinin titers compared to males, attributable to immunological factors, such as pregnancy, vaccination, or incompatible transfusions. Nonetheless, in our investigation, the limited and disproportionate female sample constrained the validity of gender-based comparisons. Future studies should aim to recruit a more balanced sex distribution to facilitate stronger conclusions regarding sex-related differences in isohemagglutinin titers. As for age distribution, the most frequent donors were 26 - 35 years old, constituting 40.3% of the total, and 69.2% of all volunteers were between 26 and 45 years old. Upon examining the distributions separately according to sex, decade, and phenotypes for each blood group, our results align with the general rates found in the Turkish blood donor population. Interestingly, our study found that blood group A was more common, unlike in Northern and Central European countries and America, where blood group O was more prevalent. Numerous studies have indicated that Caucasians have a RhD (+) phenotype frequency of 85% and RhD (-) phenotype frequency of 15% (30, 31). Similarly, in our country, we found an RhD (+) phenotype of 87% and an RhD (-) phenotype of 13% (17-19).

Blood donors are commonly registered and routinely donated in many Western countries, such as America and Europe. It appears that awareness of this issue is yet to be fully developed in our country. Largely because of insufficient health policies advocating regular blood donation, most donors in our country’s blood centers are directed rather than regular donors. Our investigation revealed that a much greater percentage of O group female donors displayed increased anti-B IgM and anti-B IgG titers than male donors. Anti-B IgM titers at 1:128 and 1:256 were significantly more prevalent among female donors (P = 0.027 and P = 0.012, respectively), while anti-B IgG titers at 1:1024 were significantly higher in females compared to males (31.3% vs. 6.9%, P = 0.005) (Figure 2).

Assessing the isohemagglutinin titers of blood donors according to sex revealed that the anti-B IgM titers in female patients with blood group O were significantly higher than those in male patients (P = 0.001; P < 0.01). This finding confirmed that isohemagglutinin titers in women were significantly higher than those in men and may indicate that female donors tend to have elevated isohemagglutinin titers. Previous investigations have observed similar tendencies, suggesting that female donors often have elevated isohemagglutinin titers, possibly attributable to immunological variables, such as pregnancy or transfusion history (20, 29). Nevertheless, our study did not gather comprehensive information regarding pregnancy or prior transfusions. Only the lack of blood transfusions in the previous year was verified. Consequently, while biological plausibility is present, the observed sex-specific variations in titer distributions must be evaluated judiciously. Additional long-term investigations that include detailed immunological histories are necessary to clarify the underlying causes of these discrepancies.

In addition to pregnancy and transfusion history, factors such as immunization status and dietary habits may also affect isohemagglutinin titers. Vaccination, especially with vaccines containing antigens that resemble blood groups, has been proposed to temporarily increase antibody titers (20, 25). Similarly, dietary patterns, particularly vegetarian or plant-based diets, have been linked to fluctuations in immunological responses, which may indirectly influence isohemagglutinin levels (20, 29). Additionally, probiotic intake has been suggested as a potential factor influencing the development of high isohemagglutinin titers (32). Nevertheless, in the current investigation, comprehensive data concerning participants’ immunization histories or dietary preferences were not obtained. Subsequent studies should methodically assess these variables to effectively address potential confounding influences and precisely characterize the dynamics of isohemagglutinin titers.

Isohemagglutinins, developed against ABO blood group antigens, play a significant role in transfusion and transplantation. Approximately 30 - 40% of allogeneic HSCT, comprising the majority of these transplants, occurs in cases of ABO blood group incompatibility. Such HSCTs can potentially lead to severe immunohaematological complications. Transfusion of blood products, both before and after transplantation in patients undergoing HSCT, is a critical factor that directly influences transplant success. Therefore, constant cooperation between blood banks and transplantation teams is vital. For transplant patients, particularly during the pre-transplantation phase or the transplant preparation stage, the demand for erythrocyte suspension frequently arises because of immunohemolysis or iatrogenic anemia. Until post-transplant engraftment occurs, a chaotic microenvironment containing recipient and donor hematopoietic cells and isohemagglutinins ensues. This makes transfusion practices challenging because of inconsistencies in ABO grouping and agglutination reactions. Within this timeframe, crafting a detailed transfusion policy is of utmost importance.

In a 10-year, retrospective study, Sheppard et al. (33) demonstrated that acute hemolytic transfusion reactions did not occur in patients who underwent plasma exchanges prior to major ABO-incompatible HSCTs. Similarly, Kimura et al. revealed delayed erythrocyte, neutrophil, and platelet engraftment in patients who underwent major ABO-incompatible allogeneic transplantation (34). This study also found an increased incidence of acute GVHD in both major and minor ABO-incompatible transplants (34). In addition, Braine et al. indicated a decrease in isohemagglutinin titers with plasma exchange (35), while Bolan and Griffith suggested a possible isohemagglutinin-dependent link between preparation regimens and the incidence of erythroid aplasia. Many studies have shown that high isohemagglutinin titers can cause complications in ABO blood-group-incompatible HSCT, thereby increasing the risk of mortality and morbidity (36, 37).

Our study was conducted on the premise that anti-donor isohemagglutinin titers in blood product components from volunteer donors could be critical for patients requiring transfusions due to post-transplant complications. In cases of ABO major-mismatch HSCT, it is important to determine the level of anti-donor isohemagglutinin. If the level is 1:32 or higher, immunoadsorption and plasma exchange are recommended to lower the risk of hemolysis. To lower the risk of hemolysis, removal of red blood cells from the graft, immunoadsorption, and plasma exchange are recommended if the anti-donor isohemagglutinin titer is ≥ 1:32.

The elevated isohemagglutinin titer in women was predicted to be influenced by fertility compared with that in men. ABO blood group incompatibility during pregnancy can lead to indirect hyperbilirubinemia in newborns due to immune hemolytic anemia. The severity of hemolysis is contingent on factors such as previous instances of hemolytic disease, maternal antibody titer, and any occurrence of intrauterine or fetomaternal bleeding at birth. Consequently, it was inferred that isohemagglutinin titers might be higher in women with a history of neonatal hemolytic disease or those who have been subjected to invasive intrauterine diagnostic or therapeutic procedures that could cause fetomaternal bleeding. The conclusion was that transfusing HSCT patients with blood products from women with this history might not be the best approach.

There was a notable difference in the sex distribution of anti-A IgM titers among individuals with blood group B, as well as anti-B IgM, IgM, IgG, and IgM titers among individuals with blood group O (P = 0.021; P < 0.05). This analysis aimed to determine the titer level at which there was a significant sex difference. Specifically, the 1:128 titer level for anti-A IgM was more prominent in women in blood group B than in men. Moreover, for women with blood group O, the titer levels of 1:128 and 1:256 for anti-B IgM, along with the 1:1024 titer level for anti-B IgG and the 1:256 titer level for anti-A IgM, were statistically more significant than for men.

The limitations of the study were the number of female donors in our study population and its single-center design. The sample size was too small to derive meaningful conclusions regarding sex and antibody titers owing to general donor habits. The skewed male predominance (95.2%) limits generalizability to female donors. Although no corrective measures have been applied to mitigate potential sources of bias, future research should employ matched sample procedures and comprehensive donor histories to mitigate the influence of these confounding variables. The strength of this study was that a fairly good number of samples were included, given that the method used for titration was manual, which is cumbersome.

In conclusion, this study conducted at the Istanbul Faculty of Medicine Blood Center provides the first examination of the distribution of isohemagglutinin titers among the Turkish population by decade and sex. This investigation, performed in Istanbul, a microcosm of Turkey, lacks comparative data owing to the absence of similar studies. Turkey is characterized by diverse ethnic groupings. However, providing a comprehensive distribution rate for ethnicity is not feasible, as ethnicity has not been surveyed in the country since 1965. Istanbul is Turkey’s most populous city. The demographic composition of Istanbul amplified Turkey’s ethnic diversity. Although this study gives us a fair idea of the prevalence of high-titer antibodies, a much larger sample size is required to show its association with specific characteristics. Although this was a single-center study, the cosmopolitan nature of Istanbul and the donor pool size increased the external validity of our results. Nonetheless, we believe that its significance lies in its uniqueness as the only study of its kind in Istanbul and, by extension, throughout Turkey. We hope that this research will illuminate future studies and guide transfusion policies employed in HSCT. Given the clinical significance of isohemagglutinin titers in ABO-incompatible HSCT, incorporating donor isohemagglutinin titer screening into transfusion protocols may enhance overall patient survival and improve transplant-related outcomes, particularly in high-risk transplant recipients. Although not performed in the current study, sensitivity analyses using stricter isohemagglutinin titer thresholds (e.g., ≥ 1:256) are suggested for future research to assess the robustness of sex-based differences.