1. Background

Osteosarcoma, the most prevalent malignancy of mesenchymal cells capable of producing osteoid or immature bone, affects long bones such as the femur, tibia, and humerus, accounting for 40% to 60% of primary malignant bone tumors (1). Histologically, osteosarcomas are subdivided into osteoblastic, chondroblastic, and fibroblastic types — comprising 76% - 80%, 10% - 13%, and 10% of cases, respectively, along with other rare variants (2).

Parosteal osteosarcoma is one of these rare variants, representing the well-differentiated end of the spectrum. It comprises approximately 4% of all osteosarcomas and is considered a rare malignant bone tumor (3). Clinical and histological findings remain of paramount importance for diagnosis and management of osteosarcoma, and POS generally has a better prognosis due to favorable response to therapy (4).

The combination of surgery and chemotherapy has significantly improved the 5-year survival rate for osteosarcoma in recent years (5). However, due to the low prevalence of POS, the impact of various pathological variables on survival is not well characterized, making it challenging to enroll sufficient numbers of patients for study. The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, which includes data from 18 cancer registries and approximately 30% of the U.S. population, offers an opportunity to assess the most recent survival rates for POS and the risk factors influencing survival.

Nomograms are powerful tools that integrate multiple prognostic variables to provide individualized risk assessments and are widely used in clinical decision-making (6). They offer personalized survival probability predictions, facilitate understanding of prognosis, inform treatment decisions, stratify patients by risk, and help determine the need for adjuvant therapies, thereby optimizing clinical management.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to identify risk factors for POS and to develop a prognostic nomogram to predict overall survival in these patients.

3. Methods

3.1. Clinical Data and Selection Criteria

The SEER data, comprising epidemiological information from 18 cancer registries in the United States, were utilized for this study. Data extraction was performed using SEER*Stat (Version 8.3.5), developed by the Surveillance Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute. The SEER database is publicly available and anonymized, so individual patient consent was not required for this retrospective research.

The "SEER research plus data, Nov. 2020 Sub (1975 - 2018)" database was selected because it includes information on treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation for POS patients. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) Diagnosis of POS according to the third edition of the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3); (2) diagnosis between 1975 and 2018; (3) POS as the first and only primary malignant tumor of bone, joint, or soft tissue; (4) comprehensive clinical data, including age, sex, race, SEER stage, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and primary site; (5) histology code 9192/3; (6) complete follow-up information, including survival time; and (7) known cause of death. To facilitate understanding of staging systems, a table comparing SEER stages and American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor Node Metastasis (AJCC TNM) staging for POS is provided (Table 1).

| SEER Stage | AJCC TNM Staging | Description a |

|---|---|---|

| Localized | I and II | T1-T2, N0, M0 |

| Regional | III | T1-T3, N1, M0 |

| Distant | IV | Any T, Any N, M1 |

Abbreviations: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; AJCC TNM, American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor Node Metastasis.

a T1, tumor ≤ 8 cm in greatest dimension; T2, tumor > 8 cm in greatest dimension; T3, discontinuous tumors in the primary bone site; N0, no regional lymph node metastasis; N1, regional lymph nodes metastasis; M0, no distant metastasis; M1, distant metastasis.

3.2. Study Variables

The study included the following variables: Age at diagnosis (categorized as under 20, 20 - 60, and over 60 years), sex, race (white, black, other), SEER stage (localized, regional, distant), surgery (yes/no), radiation (yes/no), chemotherapy (yes/no), and primary site (soft tissue or bones and joints). Overall survival, defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause, was the primary endpoint.

3.3. Mouse Double Minute 2 Amplification

In POS, mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) amplification occurs in approximately 6 - 17% of cases and is associated with p53 inactivation and poorer overall survival (7). To assess the impact of missing MDM2 data in the SEER database, an extreme-scenario sensitivity analysis was conducted, anchored to this 17% prevalence. In scenario A, 17% of patients were randomly labeled as MDM2-amplified; in scenario B, 6% were considered wild-type. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models adjusting for age, sex, race, SEER stage, surgical resection, and chemotherapy were used to estimate hazard ratios for overall survival.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R-Project version 4.0.2 and IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P-value < 0.05. Each variable underwent Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, with log-rank tests used to assess differences in survival curves. If curves crossed, indicating violation of the proportional hazards assumption, landmark analysis was applied. Multivariate Cox regression was used to identify independent predictors of survival. A nomogram was constructed to predict prognosis, and calibration curves were used to assess agreement with observed survival. Internal validation was performed using the Concordance Index (C-Index) and calibration curve, with model discrimination assessed by 10-fold cross-validation and 95% confidence intervals derived from 1,000 bootstrap resamples. Decision curve analysis was used to evaluate the nomogram’s clinical utility. Predictive accuracy for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival was assessed by time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, using the area under the curve (AUC) as the primary metric. Patients were classified into low-risk and high-risk groups based on an optimal cutoff value for the nomogram risk score, determined using the C-Index. External validation of the nomogram was performed using a testing cohort.

4. Results

4.1. Patient Baseline Characteristics

All patients diagnosed with POS from 1975 to 2018 in the SEER database were included. Out of 161 identified cases, 127 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Among these, 56 were male and 71 were female. Thirty-six patients were under 20 years old, and 6 were over 60. The median survival time was 173 months (range: 6 to 521 months). Racial distribution included 105 white, 13 black, and 9 others. The SEER stage was localized in 84 cases, regional in 38, and distant in 5. The majority of patients underwent surgery (only 5 did not). Radiation was administered to 1 patient, chemotherapy to 37. The overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 99.21%, 95.23%, and 86.66%, respectively (Table 2).

| Categories | Values |

|---|---|

| Survival time (mo) | 173 (6 - 521) |

| Age (y) | |

| < 20 | 36 |

| 20 - 60 | 85 |

| > 60 | 6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 56 |

| Female | 71 |

| Race | |

| White | 105 |

| Black | 13 |

| Others | 9 |

| SEER stage | |

| Localized | 84 |

| Regional | 38 |

| Distant | 5 |

| Surgery | |

| Surgery | 127 |

| No surgery | 5 |

| Radiation | |

| Radiation | 1 |

| No radiation | 126 |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Chemotherapy | 37 |

| No chemotherapy | 90 |

| Site | |

| Bones and joints | 127 |

| Soft tissues | 0 |

| 1-year OS rate | 125/126 a |

| 3-years OS rate | 120/126 b |

| 5-years OS rate | 104/120 c |

Abbreviations: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; OS, overall survival.

a One patient was excluded because the case was only followed up for 6 months and was still alive.

b One patient was excluded because the case only followed up for 6 months and was still alive.

c Seven patients were excluded because the follow-up time was less than 5 years and they were still alive.

4.2. Prognostic Factors for Survival in Parosteal Osteosarcoma

The 5-year survival rate did not significantly differ by age (P = 0.195), sex (P = 0.443), race (P = 0.312), or type of surgery (P = 0.073). Significant differences were observed based on SEER stage (P = 0.006) and chemotherapy (P = 0.019) (Table 3). Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that age (P = 0.213), race (P = 0.361), and sex (P = 0.104) were not significantly associated with 5-year survival (Figure 2A - C). However, distant SEER stage (P < 0.001; Figure 2D), chemotherapy (P = 0.009; Figure 2E), and absence of surgery (P = 0.025; Figure 2F) were associated with worse prognosis.

| Clinicopathological Features | Number of Cases | Vital | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | Dead | |||

| Age (y) | 0.195 | |||

| < 20 | 36 | 32 | 4 | |

| 20 - 60 | 79 | 69 | 10 | |

| > 60 | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Sex | 0.443 | |||

| Male | 52 | 46 | 6 | |

| Female | 68 | 56 | 12 | |

| Race | 0.312 | |||

| White | 99 | 84 | 15 | |

| Black | 12 | 12 | 0 | |

| Others | 11 | 10 | 1 | |

| SEER stage | 0.006 | |||

| Localized | 78 | 70 | 8 | |

| Regional | 37 | 32 | 5 | |

| Distant | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Surgery | 0.073 | |||

| Surgery | 115 | 101 | 14 | |

| No surgery | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.019 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 36 | 27 | 9 | |

| No chemotherapy | 84 | 77 | 7 | |

Abbreviation: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Multivariate analysis identified only surgical treatment as an independent predictor of favorable prognosis [HR, 0.163; 95% CI, (0.031 - 0.863)] (Table 4). Sensitivity analysis using literature-based MDM2 amplification rates yielded adjusted hazard ratios of 1.277 (95% CI, 0.531 - 3.072; P = 0.588) for 6% amplification and 1.429 (95% CI, 0.660 - 3.090; P = 0.362) for 17% amplification, confirming that missing MDM2 data did not materially alter overall survival estimates.

| Characteristics | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-Value | HR (95% CI) | P-Value | |

| Age (y) | 0.360 | - | ||

| 20 - 60 | Reference | |||

| < 20 | 0.855 (0.268 - 2.725) | |||

| > 60 | 3.279 (0.718 - 14.974) | |||

| Sex | 0.095 | - | ||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 2.476 (0.798 - 7.678) | |||

| Race | 0.154 | - | ||

| White | Reference | |||

| Others | 0.710 (0.094 - 5.377) | |||

| Black | 0.000 (0.000 - Inf) | |||

| Stage | 0.017 | 0.068 | ||

| Distant | Reference | Reference | ||

| Localized | 0.090 (0.024 - 0.341) | < 0.001 | 0.247 (0.049 - 1.246) | |

| Regional | 0.124 (0.029 - 0.525) | 0.005 | 0.227 (0.046 - 1.113) | |

| Surgery | 0.042 | 0.033 | ||

| No surgery | Reference | Reference | ||

| Surgery | 0.215 (0.049 - 0.948) | 0.163 (0.031 - 0.863) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 0.015 | 0.058 | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference | ||

| No | 0.292 (0.109 - 0.785) | 0.321 (0.099 - 1.041) | ||

4.3. Construction and Validation of Prognostic Nomogram

A nomogram was developed to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival in POS using all clinicopathological parameters (Figure 3A). The AUC values for the model were 1.000, 0.886, and 0.734 at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively (Figure 3B). Calibration plots showed the predicted risk closely matched the ideal curve (Figure 3C - E), and the C-Index was 0.712 (0.656 - 0.768). Decision curve analysis showed that the nomogram provided net benefit at 1, 3, and 5 years (Figure 3F - H).

Construction of prognostic nomogram and validation. A, nomogram for 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rate of children with parosteal osteosarcoma (POS); B, the area under the curve (AUC) values for the nomogram model at 1, 3, and 5 years overall survival; C - E, calibration plot of a nomogram for 1-year,3-years,5-years survival rate of children with POS; F-H, decision curves of the nomogram predicting ability [Note: 10-fold cross-validation Concordance Index (C-Index): 0.712 (bootstrap 95 % CI 0.656 - 0.768). Owing to only one death within 12 months among 120 patients, the 1-year AUC of 1.000 reflects an extreme leverage effect rather than overfitting; this value is therefore retained].

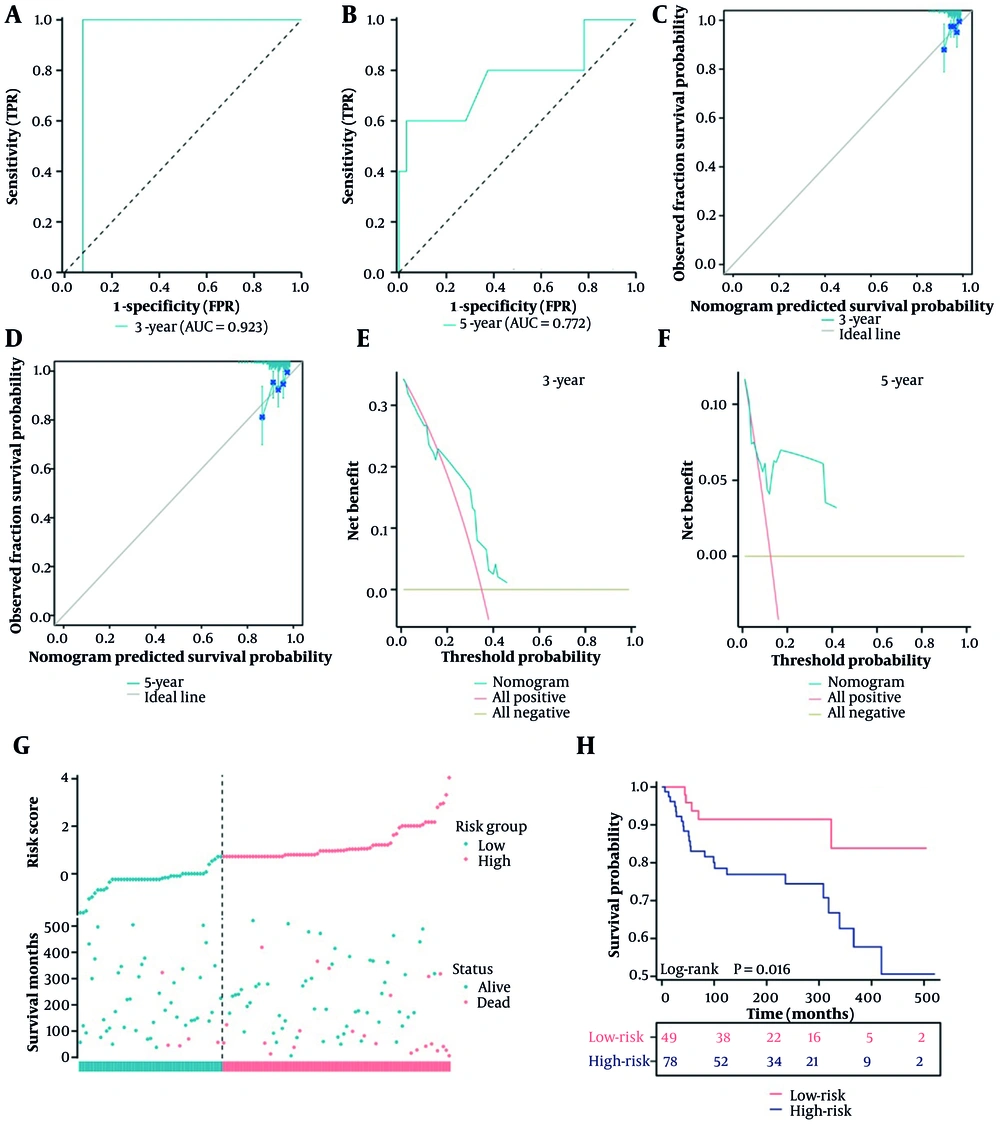

Patients were randomly divided into training and testing cohorts. Statistical analysis of variables in both cohorts yielded P-values > 0.05 (Table 5). In the testing cohort, the AUC values for 3- and 5-year survival were 0.923 and 0.772, respectively (Figure 4A and B). Calibration plots indicated good agreement between predicted and actual survival (Figure 4C and D), and the C-Index was 0.665 (0.639 - 0.691). Decision curve analysis confirmed net benefit for patients (Figure 4E and F).

| Characteristics | Total (n = 127) | Training Cohort (n = 88) | Testing Cohort (n = 39) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survival time (mo) | 173 (6 - 521) | 175 (6 - 521) | 149 (16 - 505) | 0.473 |

| Age (y) | 0.684 | |||

| < 20 | 36 | 23 | 13 | |

| 20 - 60 | 85 | 61 | 24 | |

| > 60 | 6 | 4 | 2 | |

| Sex | 0.562 | |||

| Male | 56 | 37 | 19 | |

| Female | 71 | 51 | 20 | |

| Race | 0.984 | |||

| White | 105 | 73 | 32 | |

| Black | 13 | 9 | 4 | |

| Others | 9 | 6 | 3 | |

| SEER stage | 0.152 | |||

| Localized | 84 | 60 | 24 | |

| Regional | 38 | 23 | 15 | |

| Distant | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Surgery | 0.322 | |||

| Surgery | 122 | 83 | 39 | |

| No surgery | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Radiation | > 0.999 | |||

| Radiation | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| No radiation | 126 | 87 | 39 | |

| Chemotherapy | 0.204 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 37 | 29 | 8 | |

| No chemotherapy | 90 | 59 | 31 | |

| Vital | > 0.999 | |||

| Alive | 99 | 68 | 31 | |

| Dead | 28 | 20 | 8 |

Abbreviation: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

External validation of nomogram. A and B, the area under the curve (AUC) values for the nomogram model at 1, 3, and 5 years overall survival in testing cohort; C and D, calibration plot of a nomogram for 1- , 3-, 5-years survival rate of children with parosteal osteosarcoma (POS) in testing cohort; E and F, decision curves of the nomogram predicting ability in testing cohort; G, the survival time of the high-risk and low-risk groups in testing cohort; H, the Kaplan-Meier curve of the high-risk and low-risk groups.

Based on the nomogram, the optimal risk score cutoff was 0.712. Patients with a risk score below 0.712 were classified as low-risk, and those with a score of 0.712 or higher as high-risk. Survival time was shorter in the high-risk group (Figure 4G and H). These results indicate that the nomogram is a useful and accurate tool for predicting survival in POS.

5. Discussion

The overall survival rate for osteosarcoma, a common primary bone tumor in humans, has remained largely stable for more than 20 years (8). Osteosarcoma is categorized into osteoblastic, chondroblastic, fibroblastic, telangiectatic, low-grade, small-cell, parosteal, and periosteal osteosarcomas based on the histological presentation (9). A malignant bone tumor that develops from the cortical surface of the bone is called POS. Young women are most likely to experience POS over the metaphyseal region, particularly in the long bones around the knee joint (4).

The first case of POS, a rare malignant tumor originating from the surface of the bone, was recorded in 1967 (10). It primarily affects individuals aged 10 to 39 years, most often in the posterior distal femur, and accounts for 4 - 5% of all osteosarcomas (3, 11). Additionally, researchers from Germany analyzed bone tumor data from the SEER database between 1973 and 2012. The findings showed that over a 37-year period, there were 12,931 primary malignant bone tumors in the USA, but only 252 incidences of POS among osteosarcomas, indicating that POS accounts for roughly 1.95% of primary malignant bone tumors (12). All of these findings demonstrate that the incidence of POS is low.

The 5-year survival rate for osteosarcoma has not changed significantly over the past 20 years, despite ongoing advancements in diagnostic and therapeutic methods. Parosteal osteosarcoma is a favored histological variety of osteosarcoma, and because it responds well to treatment, it has a better prognosis (13). However, POS is a malignant tumor that poses a hazard to human health, and many underlying mechanisms remain unidentified and require further investigation. Only sporadic case reports on POS were identified in our review of the literature. These low-grade osteosarcomas are typically discovered late, often following the development of a growing painful mass, due to their non-specific clinical and radiological appearance (14, 15).

Last year, a case report about POS was published by a French scholar (16). They described a 21-year-old female patient with primary POS of the thumb, who underwent tumor resection and reconstruction; however, a diagnosis of “benign exostosis” had been made nine years previously. This indicates that POS is a low-grade malignancy. On the other hand, it highlights that the diagnosis of POS remains challenging. The characteristics of POS include the lengthy and slow progression of the lesion, the radiological appearance of a sessile ossified mass with a cleavage plane separating it from the neighboring bone, and the absence of periosteal reaction (15).

If a childhood lesion that was previously painless develops into a malignant tumor, it should not be disregarded, especially if it starts to cause pain. In addition, it is important to distinguish between parosteal and periosteal osteosarcomas, both of which are low-grade osteosarcomas but are not the same histologic entity (17). The literature states that the MDM2 marker is helpful in the diagnosis of POS (7). The MDM2 amplification is a critical diagnostic marker for POS, as it is present in approximately 83% of these cases (7).

However, the SEER database, which we utilized for this study, does not capture molecular information such as MDM2 amplification status. This is a known limitation of the SEER database, which primarily focuses on demographic, clinical, and pathological data but lacks detailed molecular profiling. In our study, because the SEER database does not include molecular information on MDM2 amplification status, we were unable to directly identify or exclude MDM2-negative cases. Consequently, our analysis included all available POS cases without screening based on MDM2 status.

The MDM2 amplification is a known prognostic factor in POS, as described in previous literature, where approximately 83% of cases exhibit MDM2 amplification. This implies that in our study, the majority of patients likely had MDM2 amplification, which could potentially influence survival outcomes. However, due to the absence of specific MDM2 status information, we are unable to accurately assess the impact of MDM2-negative cases on the study results. Given the importance of MDM2 amplification in the diagnosis and management of these tumors, we acknowledge that the absence of this data restricts our ability to fully characterize the cases included in our study.

Future research should aim to incorporate molecular data, such as MDM2 amplification status, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the disease and improve diagnostic accuracy. We suggest that researchers consider using alternative data sources or conducting additional molecular analyses to supplement the information available from SEER.

A total of 161 incidences of POS were identified in the "plus data, Nov. 2020 Sub (1975 - 2018)" dataset using the SEER database. Ultimately, this study included 127 patients. The overall patient survival rate at 5 years was 86.66% during follow-up. Ruengwanichayakun et al. reported 195 patients with POS from 1900 to 2018, with a 5-year survival rate of 87.69% (11). They found that, at the final follow-up, 155 patients (79.5%) were still alive and free of disease, 8 patients (4.1%) were alive but had active disease, 23 patients (11.8%) had died due to the disease, and 9 patients (4.6%) had died from causes unrelated to the disease. Additionally, they discovered that patients with dedifferentiated POS had significantly worse survival rates compared to those with conventional tumors, with 5-year survival rates of 65% versus 96%, and 10-year survival rates of 60% versus 96%. In a different study conducted in 2015, 80 patients were examined and a 5-year survival rate of 91.8% was reported (18). The 5-year and 10-year disease-specific survival rates for dedifferentiated high-grade tumors were 81.8% at both 5 and 10 years, compared to 98% and 94% at 5 and 10 years, respectively, for low-grade tumors. These findings demonstrate that POS is a subtype of osteosarcoma with a favorable prognosis and a relatively high five-year survival rate. Furthermore, earlier research was consistent with our findings.

In a survival analysis, it was found that distant stage in SEER staging and absence of surgery were also poor predictors of outcome in POS. These results are similar to findings in many solid tumors, where both distant metastasis and surgical failure are associated with poor prognoses (19). Interestingly, patients with POS who received chemotherapy had a worse prognosis and shorter survival time than those who did not receive chemotherapy. This finding is contrary to the prevailing view that chemotherapy improves survival in osteosarcoma, as supported by previous studies (20). In POS, one study found that chemotherapy had no significant impact on survival. According to the authors, the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of POS is not as clear as it is in the treatment of conventional osteosarcoma (18). In our study, we observed that chemotherapy was associated with worse survival (P = 0.009), which is likely due to confounding by indication, particularly advanced-stage bias. This bias may occur when patients with more advanced disease are more likely to receive chemotherapy, and their poorer prognosis is attributed to the treatment rather than the underlying disease severity.

We further noted that the inverse association between chemotherapy and poorer survival is likely confounded by SEER stage. Poorly differentiated tumors were concentrated in distant-stage disease (20/22, 91% received chemotherapy), whereas well or moderately differentiated tumors predominated in localized and regional stages (73/98, 74% received chemotherapy). Other contributing factors include the small number of cases included in our analysis and the possibility that earlier research on osteosarcoma did not specifically differentiate between histological subtypes of osteosarcoma.

Additionally, we note that the SEER database does not provide information on tumor grade and differentiation status. This limitation prevents us from further adjusting for these important factors in our current study, thereby restricting our ability to conduct a more in-depth analysis of the relationship between chemotherapy and survival outcomes. The SEER database, like many population-based registries, is subject to potential misclassification bias. This can occur due to errors in data coding, incomplete information, or the subjective interpretation of medical examiners when determining the cause of death. Furthermore, tumor characteristics such as histological subtype or aggressiveness, which can influence prognosis, may not always be accurately captured in registry data. The inclusion of dedifferentiated POS could potentially lead to misclassification bias, as these cases may have different prognostic profiles compared to other subtypes. Dedifferentiated POS is a special subtype of osteosarcoma, typically arising from low-grade POS, but in some cases, it can transform into a high-grade sarcoma (11, 18). Such dedifferentiated POS usually carries a higher risk of metastasis and a worse prognosis. However, the SEER database does not differentiate this subtype. Therefore, future studies will need to explore additional data sources and validation methods to address the potential for bias.

In our study, multivariate analysis showed that the only other independent indicator of a good prognosis for POS was surgical treatment. The fact that these findings are consistent with earlier publications on osteosarcoma suggests that there are similarities between POS and osteosarcoma (21).

Finally, using data on age, sex, race, chemotherapy, and surgery, we developed a nomogram to predict the survival rate of POS. We can calculate a total score based on the personalized data and its corresponding value, which can then be used to estimate the survival rate. Additionally, calibration plots revealed that the predicted risk was extremely close to the ideal curve, indicating strong predictive power.

The nomogram model developed in this study serves not only as a novel tool for clinicians to predict individualized survival probabilities for patients with POS, but also aids in better understanding patient prognosis. By integrating key clinical and pathological variables, the nomogram assists physicians in more accurately assessing patient risk levels during the treatment decision-making process. This may be significant for selecting the most appropriate treatment options, formulating personalized treatment plans, and determining the frequency of monitoring and follow-up. Furthermore, the nomogram can act as a communication aid, helping doctors clearly explain potential disease outcomes and treatment choices to patients and their families, thereby enhancing patient understanding and engagement in the treatment process.

Although the nomogram demonstrates good predictive performance, its application in clinical practice still requires further research and validation. Future efforts should focus on exploring the applicability of the nomogram in various clinical settings and assessing its potential impact on improving patient outcomes. In this way, the nomogram is expected to become a valuable component in the comprehensive management of patients with POS.

We provide the following example to illustrate the clinical application of the nomogram: Consider a 70-year-old female patient of white ethnicity with localized disease who has not undergone surgery or chemotherapy. According to the nomogram scoring rules, this patient would receive the following points: 22 points for age (> 60 years), 16 points for female sex, 100 points for white race, 0 points for localized stage, 10 points for no surgery, and 0 points for no chemotherapy. The total score would be 148 points. This score corresponds to a 1-year survival probability of greater than 95%, a 3-year survival probability of approximately 75%, and a 5-year survival probability of approximately 40%. This example demonstrates how clinicians can use the nomogram to quickly estimate survival probabilities based on patient-specific characteristics, thereby aiding in individualized treatment decision-making.

We acknowledge that our study has several important limitations. The majority of the population in the SEER database is white, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other racial and ethnic groups. To more comprehensively assess the impact of racial differences on survival rates in POS, we conducted a literature search outside the SEER database. Carter et al. (22) analyzed survival rates in patients with POS and found no significant impact of race. Additionally, the SEER database lacks detailed information on specific chemotherapy regimens, which is crucial for understanding treatment effects. Furthermore, SEER does not capture molecular details such as MDM2 amplification status, a key diagnostic marker for certain malignancies. These limitations in data granularity restrict our ability to fully assess the impact of these factors on patient outcomes.

Moreover, our study cohort is relatively small, and certain events, such as distant stage, undergoing surgery, and receiving radiation, are rare. The small sample size and single early death limit the reliability of the 1-year AUC. This reduces the statistical power of our analyses and may limit the robustness of our findings. Model discrimination was assessed by 10-fold cross-validation, with 95% confidence intervals derived from 1,000 bootstrap resamples. Although the training set demonstrated good internal validation performance with a C-Index of 0.712 (95% CI 0.656 - 0.768) through 10-fold cross-validation and 1,000 bootstrap resamples, the lower C-Index in the external validation cohort (0.665) suggests limited generalizability to new datasets. Future work will focus on enhancing model robustness and generalizability by expanding the sample size and incorporating multicenter data (22).

Given these limitations, we emphasize the need for large-scale, comprehensive population-based studies to provide clearer insights into the incidence and survival trends of POS. Future research should aim to address these limitations by incorporating more detailed clinical and molecular data and by validating findings in diverse and larger cohorts.

5.1. Conclusions

In individuals with POS, the current investigation identified risk variables associated with survival. Age, gender, SEER stage, and treatment were found to be independent predictors of prognosis in POS. A better understanding of these characteristics and prognostic factors could assist clinicians in optimizing the management and outcomes of patients with POS.

![Construction of prognostic nomogram and validation. A, nomogram for 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rate of children with parosteal osteosarcoma (POS); B, the area under the curve (AUC) values for the nomogram model at 1, 3, and 5 years overall survival; C - E, calibration plot of a nomogram for 1-year,3-years,5-years survival rate of children with POS; F-H, decision curves of the nomogram predicting ability [Note: 10-fold cross-validation Concordance Index (C-Index): 0.712 (bootstrap 95 % CI 0.656 - 0.768). Owing to only one death within 12 months among 120 patients, the 1-year AUC of 1.000 reflects an extreme leverage effect rather than overfitting; this value is therefore retained]. Construction of prognostic nomogram and validation. A, nomogram for 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival rate of children with parosteal osteosarcoma (POS); B, the area under the curve (AUC) values for the nomogram model at 1, 3, and 5 years overall survival; C - E, calibration plot of a nomogram for 1-year,3-years,5-years survival rate of children with POS; F-H, decision curves of the nomogram predicting ability [Note: 10-fold cross-validation Concordance Index (C-Index): 0.712 (bootstrap 95 % CI 0.656 - 0.768). Owing to only one death within 12 months among 120 patients, the 1-year AUC of 1.000 reflects an extreme leverage effect rather than overfitting; this value is therefore retained].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/31710/60563954297dfeca3869b8a5372dd0055829d1a7/ijp-35-6-157542-i003-preview.webp)