1. Background

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common extracranial tumor in children, accounting for 8 - 10% of all childhood cancers and 15% of pediatric oncology deaths. It originates from the sympathoadrenal lineage of neural crest cells and specifically affects the adrenal medulla or other sites such as paraspinal sympathetic ganglia (1, 2).

In developed countries, despite notable advancements in the 5-year survival rate, childhood cancer remains the second leading cause of death. Cancer at an early age is generally uncommon, accounting for a small fraction of all cancer cases. According to GLOBOCAN 2012 estimates, it constitutes approximately 1% of all cancers (3). In Iraq, childhood cancer represents about 6.7% of all cancers, which may be attributed to the demographic structure of the Iraqi population, where children under age 15 comprise about 40% of the total residents (4).

Recent studies suggest that tumor cells possess the ability to suppress the immune system within their surrounding microenvironment (5). Tumor cells can evade host immune responses through different mechanisms, such as loss of tumor cell antigenicity to escape immune detection or downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. Furthermore, immune evasion may involve the recruitment of immunosuppressive inflammatory cells and attenuation of T lymphocyte co-stimulation (6, 7).

Many inhibitory ligands, such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), are utilized by cancer cells as a primary mechanism to suppress the immune response. The PD-L1 is a co-inhibitory receptor glycoprotein expressed on the surface of various immune cells, particularly natural killer cells, monocytes, T-cells, and B-cells. Its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 bind to PD1 and activate the checkpoint inhibitor pathway to suppress T-cell activity and evade immune surveillance. The PD-L1 is overexpressed in many solid tumors, including carcinomas and melanoma (8-13). Recently, the role of immune checkpoint molecules in the tumor microenvironment has received increasing attention (14). Therefore, one of the most promising therapeutic strategies involves targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis to restore the patient’s immune response and enhance T-cell-mediated tumor destruction (15).

Positive PD-L1 immunostaining is increasingly regarded as a potential predictive biomarker for diagnosing patients with advanced or end-stage tumors who are more likely to respond to anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy (16, 17). A meta-analysis investigating the role of PD-L1 in solid tumors has highlighted that the relationship between PD-L1 expression levels and patient survival may vary significantly depending on tumor type (18). In pediatric oncology, the prevalence of PD-L1 expression and the feasibility of using anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies are only beginning to be investigated. To date, four studies have suggested inconsistent findings across various childhood cancers, including NB. Indeed, the efficacy of PD-1 inhibitors in treating NB remains an open area of research (19, 20).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to evaluate PD-L1 expression in NB tissues and explore its association with clinicopathological features. Understanding the expression patterns and potential prognostic role of PD-L1 could provide insight into immune evasion mechanisms in NB and inform future immunotherapeutic strategies.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

The current study is a cross-sectional retrospective study including 28 patients diagnosed with NB. The data were collected from an oncology center in Karbala province for patients admitted during the period from January 2018 to January 2023. Ten cases were later excluded from the study due to inadequate tissue preservation or insufficient viable tumor material for evaluation. All included samples were archival and anonymized, and the study was conducted under institutional ethical approval.

All patients were children less than 10 years of age who were diagnosed with NB. For all patients, biopsies were performed and the histopathological diagnosis for hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides was confirmed by two histopathologists. Corresponding data, including gender, age at diagnosis, tumor location (adrenal gland or not), stage [International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS): 1, 2, 3, 4], risk stratification, histological type, favorability, and Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index, were all recorded.

3.2. Programmed Death Ligand 1 Immunohistochemistry Staining

After deparaffinization and antigen retrieval, the slides were incubated with primary antibody against PD-L1 [1:100; clone E1L3N®, Isotype: rabbit IgG.13684S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA] overnight at 4°C. The staining kit used was PathnSitu PolyExcel detection system (PathnSitu, UK) and staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complete circumferential or partial linear plasma membrane staining above a 1% threshold was regarded as indicating a positive PD-L1 expression (21). As a positive control, the antibody labels the placenta. Sections untreated with primary antibody (PD-L1) were considered as negative controls for each set of slides. Parallel positive and negative control sections were processed with each set of immunostaining.

The immunostaining was scored based on membranous expression, as per manufacturer guidance and previous literature (22-24). Only viable tumor cells were evaluated. The PD-L1 positivity was defined as complete circumferential or partial linear plasma membrane staining in ≥ 1% of tumor cells. Only tumor cells were evaluated in this study. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells were not assessed.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version v.26. Descriptive statistics were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. The chi-square test was used to evaluate associations between categorical variables, such as PD-L1 expression and clinicopathological features. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The sample size for the immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was relatively small (n = 18), which may limit the generalizability of the findings and the ability to control for potential confounding variables. To assess the adequacy of the sample size, a post hoc power analysis was performed based on the observed chi-square value (χ2 = 6.923, df = 1, P = 0.009) for the association between PD-L1 expression and histological subtype. The resulting effect size (w = 0.62) yielded a statistical power of approximately 83% at a significance level of α = 0.05. These results suggest that, despite the limited sample size, the analysis was sufficiently powered to detect meaningful associations.

4. Results

4.1. Patient’s Characteristics

The current study involved a total of 28 patients; ten patients were excluded because of deficient data. Therefore, the sample size was 18 patients: Ten males (55.6%) and eight females (44.4%) with a male:female ratio of 1.25:1. The median age at diagnosis was 24 months. Six of the patients (33.3%) presented at age below 18 months while 12 patients (66.7%) were older than 18 months.

The site of the tumor at time of diagnosis was adrenal in 15 patients (83.3%), thoracic in two patients (11.1%), and paraspinal in one patient (5.6%). Most of the patients in this study (8) presented with stage 4 (55.6%), five patients were in stage 3 (27.8%), two patients were in stage 2 (11.1%), and one patient (5.6%) was in stage 1. The majority of patients were of low-risk group 9 (50%) followed by high-risk group, which included 7 patients (38.9%).

According to the histological subtype of NB, most of the patients 8 (44.4%) were diagnosed with poorly differentiating NB, five patients (27.8%) had the undifferentiating subtype, followed by differentiating and nodular ganglio- NB types forming 3 (16.7%) and 2 (11.1%), respectively. Half of the patients, 9 (50%) presented with favorable histological type, while the other half presented with unfavorable histology. The Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index was low (< 100/5000) in most of the patients, 12 (66.7%), and high (> 200) in one patient (5.6%). In the remaining 5 patients (27.8%), the index value was intermediate.

4.2. Programmed Death Ligand 1 Immunostaining

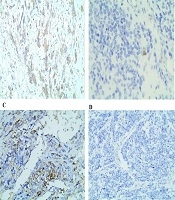

In the current study, PD-L1 immunostaining was positive in 5 (27.8%) patients and negative in the remaining 13 (72.2%) patients as seen in Figure 1 A-D. The patient’s characteristics and immunohistochemical staining results are presented in Table 1.

Membranous and cytoplasmic expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) in neuroblastoma (NB) samples. A, PD-L1 expression predominantly observed in maturing ganglion cells; B, membranous staining pattern of PD-L1; C, cytoplasmic staining pattern of PD-L1 (higher magnification of 400X); D, negative expression of PD-L1 in a representative sample of a NB patient (magnification of 100X).

| Parameters | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 (55.6) |

| Female | 8 (44.4) |

| Age of patients (mo) | |

| < 18 | 6 (33.3) |

| > 18 | 12 (66.7) |

| Site of tumor | |

| Adrenal | 15 (83.3) |

| Thoracic | 2 (11.1) |

| Paraspinal | 1 (5.6) |

| Stages | |

| One | 1 (5.6) |

| Two | 2 (11.1) |

| Three | 5 (27.8) |

| Four | 10 (55.6) |

| Risk stratification | |

| High | 7 (38.9) |

| Intermediate | 2 (11.1) |

| Low risk | 9 (50.0) |

| Histological subtypes of NB | |

| Differentiating | 3 (16.7) |

| Undifferentiating | 5 (27.8) |

| Poorly differentiating | 8 (44.4) |

| Ganglio-NB | 2 (11.1) |

| Histology | |

| Favorable | 9 (50) |

| Unfavorable | 9 (50) |

| Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index | |

| < 100/5000 | 12 (66.7) |

| 100 - 200 | 5 (27.8) |

| > 200 | 1 (5.6) |

| PDL1 immunostaining | |

| Positive | 5 (27.8) |

| Negative | 13 (72.2) |

Abbreviations: NB, neuroblastoma; PDL1, programmed death ligand 1.

4.3. The Association Between Clinicopathological Parameters and PD-L1 Expression

There was a positive statistical correlation between PD-L1 expression and the histological subtypes of NB (P = 0.02); all the differentiating type of NB showed positive PD-L1 immunostaining, while most of the undifferentiating, poorly differentiating and ganglio-NB were negative for PD-L1 staining, forming (80%), (87.5%) and (100%) respectively.

Also, a positive statistical correlation was found between PD-L1 and the histological favorability of NB (P = 0.009), in that all 5 positive PD-L1 cases were of unfavorable histological type, forming (55.5%) of the total (25) cases with this type, while all cases of favorable histology (100%) were negative for PD-L1. The odds ratio (OR) for having unfavorable histology in PD-L1 positive cases was 20.00 (95% CI: 1.49 - 268.13), indicating a strong association, though the wide CI reflects the small sample size and should be interpreted with caution.

The PD-L1 showed a positive statistical relation with risk stratification of NB patients (P = 0.03), in that (57.1%) of patients in the high-risk group showed positive PD-L1 immunostaining, meanwhile all low-risk group (100%) were negative for PD-L1.

The PD-L1 showed no significant statistical relation with age (P = 0.7), gender (P = 0.4), site of the primary tumor (P = 0.6), stages (P = 0.7) and Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index (P = 0.6). The relation of PD-L1 to the clinicopathological parameters of patients with NB was demonstrated in Table 2.

| Clinicopathological Parameters | PDL1-Positive | PDL1-Negative | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mo) | 0.7 | |||

| < 18 | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.6) | 6 | |

| > 18 | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | 12 | |

| Gender | 0.4 | |||

| Male | 2 (20) | 8 (80) | 10 | |

| Female | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 8 | |

| Site of tumor | 0.6 | |||

| Adrenal | 4 (26.6) | 11 (73.3) | 15 | |

| Thoracic | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 | |

| Paraspinal | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 | |

| Stages | 0.1 | |||

| One | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 | |

| Two | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 | |

| Three | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 5 | |

| Four | 4 (40) | 6 (60) | 10 | |

| Risk stratification | 0.03 b | |||

| High | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.8) | 7 | |

| Intermediate | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 | |

| Low risk | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 9 | |

| Histological subtypes of NB | 0.02 b | |||

| Differentiating | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 3 | |

| Undifferentiating | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 5 | |

| Poorly differentiating | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 8 | |

| Ganglio-NB | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 2 | |

| Histology | 0.009 b | |||

| Favorable | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 9 | |

| Unfavorable | 5 (55.5) | 4 (44.4) | 9 | |

| Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index | 0.6 | |||

| < 100/5000 | 3 (25) | 9 (75) | 12 | |

| 100 - 200 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) | 5 | |

| > 200 | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 |

Abbreviations: NB, neuroblastoma; PDL1, programmed death ligand 1.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b A P-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

5. Discussion

A pair of adverse immune costimulatory molecules, programmed death 1 (PD-1) and PD-L1, exist. The tumor cells that evade the immune system’s attacks are partially mediated by the adverse immunomodulatory influence of PD-L1, the signaling cascade that exists on the exterior of many types of tumor cells. Targeted PD-L1 or PD-1 inhibition exhibits some therapeutic results in clinical studies of different malignancies and has a promising future. The majority of researchers have used an immunohistochemical procedure to detect PD-L1 expression in carcinoma of the liver, lung, and other tumor tissues. However, the extent of its expression varies among tumor types. Tumor incidence, growth and development, therapy responsiveness, and outcome are all correlated with PD-L1 expression (26).

In the current study, most of the collected cases were older than 18 months with a median age of 24 months; the male to female ratio was 1.25:1, the predominant site of the tumor was adrenal, the majority of the patients presented with stage four, and most of the cases were of low-risk group. These results seem to be compatible with another study done in Iraq-Kurdistan Region- Sulaimani, which states that the median age of patients was 24 months, the male:female ratio was 1.48:1, and the primary site of the tumor was abdominal (66.12%) with the majority of the patients (69.35%) being in stage four of the tumor, with the exception that most of the patients included in that study (54.84%) were of high-risk group (1).

A similar picture was demonstrated in another recent Iraqi study in Basra, which recorded most of its patients in stage four, forming about (52.4%); again, the primary site of tumor was adrenal in about (68.7%) of the cases (27, 28). A similar figure was documented in another Iranian study, which showed male predominance (66.6%) of the collected cases, the median age at diagnosis was 30 months, most of the cases (75%) were older than 18 months, in the majority of cases the tumor was adrenal in (75%) of cases, and about (70.6%) of cases presented with stage IV at time of diagnosis (26).

This greater median age and higher percentage of advanced disease at diagnosis in the current study could be the result of a possible delay in the disease’s diagnosis in our community due to poor family awareness of the condition and the lack of a screening program (1).

Most of the patients in the current study presented with poorly differentiating histological type of NB, forming about 8 (44.4%), followed by five patients (27.8%) with undifferentiating subtype; while in Basra most of the cases were of undifferentiating subtype, forming 168 (93.8%), followed by ganglio NB with 11 (6.1%) of the cases.

Parallel results to this study were documented by a study done in Saudi Arabia, which demonstrated a male predominance (52.5%) of the collected cases, the median age at diagnosis was 18.5 months, most of the patients (26; 61.9%) were above 1 year, 22 (52%) of cases were of low and intermediate risk group, in 17 (77.3%) cases the primary site of tumor was adrenal, 34 (81.0%) patients presented with poorly differentiating histological type as in the current study, and 26 patients (61.9%) had a favorable histology as in our study (26).

An additional Omani study showed that most of the cases involved in the study were of undifferentiated NB, forming about 46.4% of the sample size, with nonconclusive histological types forming 34% of the sample size. This discrepancy between the results of the current study and those of other studies may be due to a number of constraints. First, because it was retrospective, it was prone to missing data and potential errors. Another flaw was the limited sample size (29, 30).

In this study, PD-L1 immunostaining was positive in (27.8%) patients, and its expression showed a positive statistical correlation with risk stratification groups of patients, whether high, intermediate, or low risk groups. Also, there was a positive relation with the histological subtypes of NB, as differentiating, poorly differentiating, undifferentiating, and ganglio-NB. A positive statistical relation between PD-L1 and histological types of NB as favorable or unfavorable. No statistical correlation was found between PD-L1 and the age of the patients, sex, stages of NB, and the site of the primary tumor (30, 31).

In comparison with other studies, a study done stated that PD-L1 expression was documented in (35%) of the involved cases and there was no significant relation between PD-L1 and age, gender, or stage of the tumor (21). Another study by Majzner et al. (22) documented that PD-L1 expression was seen in (14%) of cases only. Another study by Aoki et al. (20) reported a low frequency of PD-L1 expression in pediatric tumors, including NB of 18 cases, which showed no PD-L1 expression (0%). An additional study also reported that five (12%) of 41 specimens with NB were positive for PD-L1 immunostaining, meanwhile Chowdhury et al. (19) reported higher PD-L1 expression in 66 (57%) of 115 pediatric solid tumors, including high-risk NBs (20, 22, 26).

In another study by Saletta et al. (32), PD-L1 expression was seen in 48 (18.9%) of cases with NB and, in parallel to the current study, stated that PD-L1 expression was not associated with sex, age, disease stage at diagnosis, or Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index, while it was significantly more common in favorable histology biopsy specimens and in low- or intermediate-risk patients. Additional study by Liao et al. (26) revealed that the positive rate of PD-L1 was 57% and (34%) respectively (20, 22, 26).

Several technical limitations like the age of the biopsy material, the fixation methods used, the antigen retrieval methods, and the assessment of PD-L1 immunostaining and scoring may all be contributing factors to the variance in the results (32). Differences in the numbers of cases in these studies, the quantity of tumor tissues in tissue samples, how the pathologists interpret slides, and other subjective factors could all influence the results. Therefore, it is still debatable whether PD-L1 expression can determine a NB patient’s prognosis, and future research on this subject still requires greater prospective analysis (32, 33).

5.1. Conclusions

Although some limitations of this study exist, we conclude that PD-L1 can give an impression about some important prognostic factors of NB, such as risk stratification groups, the histological subtypes, and whether the tumor is of favorable histology or not. Future larger studies are still needed to assess the relation of PD-L1 on the clinical outcome as a therapeutic target, survival rate, and recurrence of tumor.

5.2. Study Limitations

Survival outcome data, including progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival, are one of the key limitations of this study. Our findings were limited to IHC expression without correlation to long-term clinical outcomes. This limitation was primarily due to incomplete follow-up data and the retrospective nature of our study, which restricted access to consistent and comprehensive survival information for the included patient cohort. Absence of survival data limited our ability to conclude the prognostic value of PD-L1 in NB. Therefore, we recommend more studies with larger sample sizes, extended follow-up, and incorporation of a broader panel of immune checkpoint markers for a more comprehensive immune profiling and detailed clinical outcome results to validate the prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression. Additionally, a degree of selection bias may be present due to the exclusion of 10 out of 28 cases as a result of poor tissue quality or suboptimal fixation. While necessary to ensure reliable immunohistochemical evaluation, this limitation may affect the generalizability of our findings to the broader NB population.