1. Introduction

Waardenburg syndrome (WS; MIM #193500) is an auditory-pigmentary syndrome initially delineated in 1951, with a population prevalence of about 1 in 42,000 individuals. It is characterized by congenital sensorineural hearing loss and pigmentary abnormalities, including in the hair and iris (1). The WS can also manifest as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (HH) and anosmia (2), which are the primary clinical manifestations of Kallmann syndrome (KS; MIM #308700) (3). The KS results from abnormal development of olfactory axons and disruption of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neuron migration during embryonic development (4). There are over 20 genes associated with KS, including ANOS1 and FGFR1 (5). The WS is further divided into 4 types based on additional features. SOX10, initially discovered in WS (1), is a transcription factor essential for developing the neural crest and peripheral nervous system. Approximately 15% of WS type II patients and 45% of WS type IV patients are associated with SOX10 (6). Recent research has also found that mutations in SOX10 are associated with KS (2).

This case study presents a novel SOX10 mutation (c.433_c.435delCTG, p.L145del) identified in a patient diagnosed with both KS and WS type II. The identification of this novel in-frame deletion mutation adds to the spectrum of SOX10 mutations, providing valuable insights into the genetic heterogeneity of these conditions and offering crucial clues for future genetic investigations into SOX10-related disorders.

2. Case Presentation

A 15-year-old male patient was referred to our outpatient clinic due to small testicles and hearing loss. The patient was born to non-consanguineous Chinese parents without delayed meconium excretion. After birth, blue irises and hearing loss were observed. During adolescence, the patient had small testicles and experienced delayed sexual development. Additionally, he exhibited olfactory dysfunction and had weaker motor and linguistic skills compared to his peers. His parents reported that he achieved developmental milestones, such as walking and speaking, later than expected for his age, though formal assessments were not performed. In contrast, his younger brother was in good health.

The patient exhibited the following characteristics: His height was 169.7 cm (-0.01 SDS), weight was 49.5 kg, Body Mass Index (BMI) was 17.2 kg/m2, and blood pressure was 106/63 mmHg. He had bilateral sensorineural hearing loss managed with hearing aids. Upon physical examination, a blue iris was observed, and there was no evidence of a moon face. The patient had a stretched penis and a small bilateral testicular volume of 2 mL (photographs were not taken due to parental disapproval, but written informed consent was obtained for genetic testing and publication of anonymized data, including imaging and molecular findings).

Endocrine testing revealed a decreased testosterone level (20.15 ng/dL, compared to the reference range of 142.39 - 923.14 ng/dL), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH; 1.06 mIU/mL, reference range: 0.95 - 11.95 mIU/mL), and luteinizing hormone (LH; 0.11 mIU/mL, reference range: 0.57 - 12.07 mIU/mL; Table 1). After a formal GnRH stimulation test and 3 days of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (1500IU, QD, im) stimulation, the peak LH level was 1.4 mIU/mL, and the peak FSH level was 5 mIU/mL. These findings suggest an inactive gonadal axis and secondary testicular dysfunction, consistent with HH. Clinical assessment confirmed anosmia, though formal olfactometry was not performed. Corticotropin (ACTH), cortisol, thyroid function, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) were all within normal ranges.

| Hormones | Baseline | Peak Level After GnRH/hCG Stimulation | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| T (ng/dL) | 20.15 | 67.12 | 142.39 - 923.14 |

| AD (ng/dL) | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 - 3.1 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 0.11 | 1.4 | 0.57 - 12.07 |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 1.06 | 5 | 0.95 - 11.95 |

| ACTH (pg/mL); 8 a.m. | 30 | - | 0.00 - 46.00 |

| COR (µg/dL); 8 a.m. | 14.40 | - | 5.00 - 25.00 |

| TSH (mIU/L) | 1.52 | - | 0.350 - 4.940 |

| FT4 (pmol/L) | 13.42 | - | 9.01 - 19.05 |

| FT3 (pmol/L) | 4.46 | - | 2.43 - 6.01 |

Abbreviations: GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; hCC, human chorionic gonadotropin; T, testosterone; AD, adrenaline epinephrine; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; ACTH, corticotropin; COR, cortisol; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; FT4, free thyroxine level 4; FT3, free thyroxine level 3.

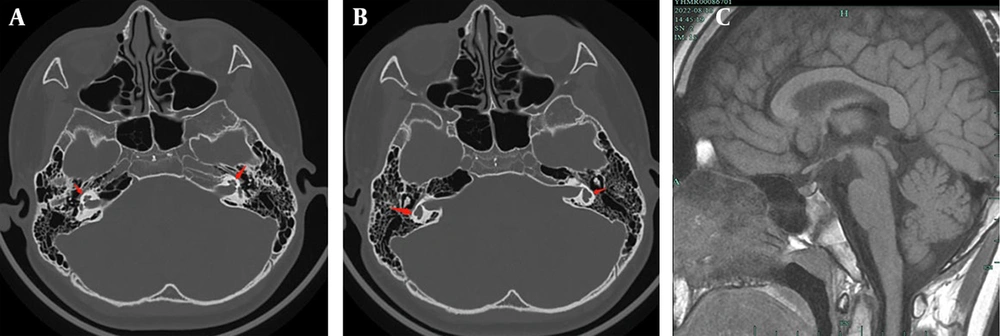

Scrotal ultrasound demonstrated decreased testis sizes (right side volume: 1.4 × 0.7 × 1.1 cm; left side volume: 1.7 × 0.7 × 1.1 cm). Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cochlear computed tomography (CT) did not reveal any abnormalities, although the semicircular canals appeared short and thick (Figure 1).

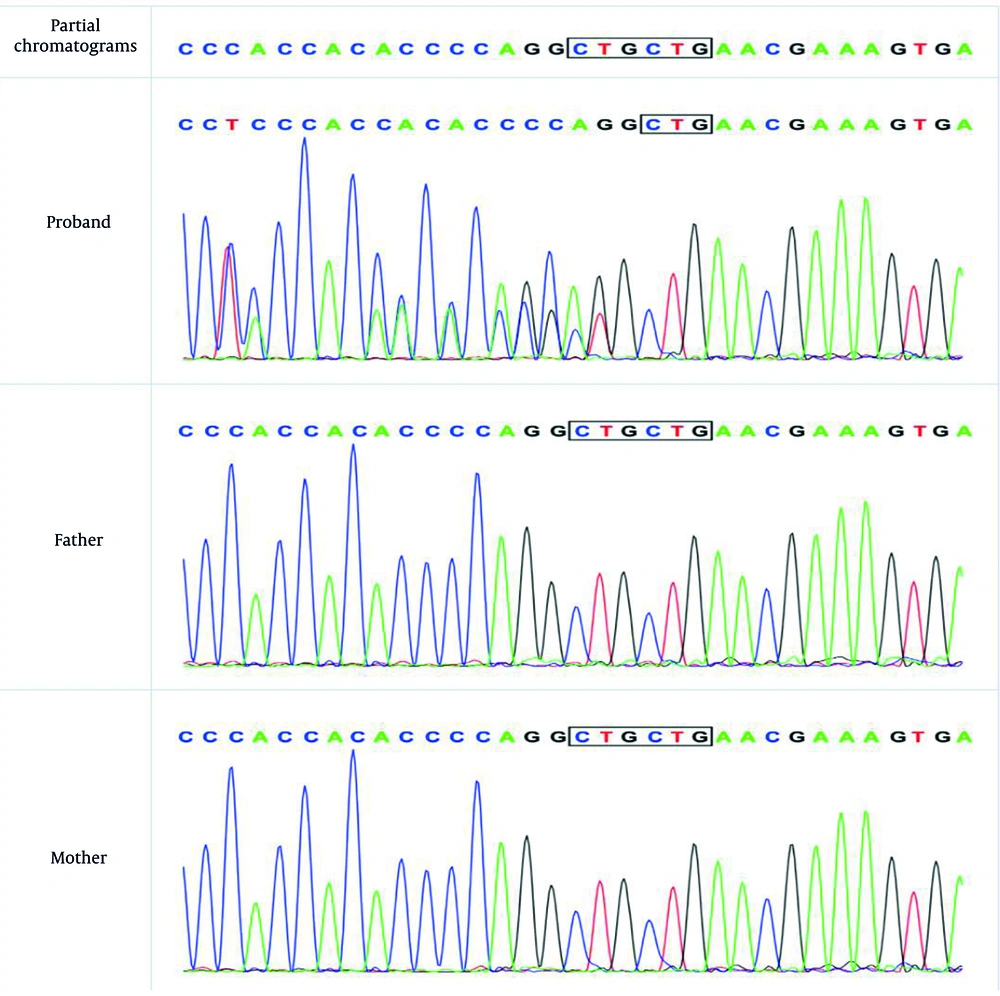

A trio-WES analysis was performed using an Illumina sequencing platform, achieving an average sequencing depth of > 100X. The bioinformatics pipeline involved alignment to the human reference genome using BWA, variant calling with GATK, and annotation with ANNOVAR. This analysis revealed a heterozygous mutation (c.433_c.435delCTG, p.L145del) of the SOX10 gene (Figure 2).

The results also confirmed a heterozygous de novo mutation, meaning it was present in the affected individual but not detected in either parent, which was further validated by Sanger sequencing. According to MutationTaster (disease-causing, score = 1) software, the detected variation was related to the disease. After searching the Human Genetic Variation Database, gnomAD browser, and 1000 Genome Browser, this particular variant was undetected. Based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) guidelines (2019), this novel heterozygous mutation (c.433_c.435delCTG, p.L145del) in SOX10 is classified as likely pathogenic. This classification is supported by strong pathogenic evidence (PS2) due to its de novo occurrence in a phenotype-related and kinship-confirmed family, supporting pathogenic evidence (PM2_Supporting) as it is undetected in control databases, and moderate pathogenic evidence (PM4) as it is an in-frame deletion predicted to disrupt protein function. We have submitted the novel SOX10 variant (c.433_c.435delCTG, p.L145del) to the China National Center for Bioinformation. We used ITASSER (7-9) (https://zhanggroup.org/ITASSER/) to predict protein structure and function. Additionally, we used PYMOL (https://pymol.org/2/) to compare the mutated proteins. This mutation caused a disruption in the protein structure (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

3. Discussion

In this report, we describe a patient presenting with a combination of KS and WS type II. The patient exhibited congenital sensorineural hearing loss and pigmentary abnormalities (blue iris) without Hirschsprung disease, which are the primary characteristics of WS type II. He also manifested certain characteristics of KS, including HH and anosmia. Genetic testing revealed a novel heterozygous mutation in the coding sequence of exon 3 of SOX10. SOX10 belongs to the SOX [SRY-related high-mobility group (HMG) box] family of transcription factors, encoding a 466-amino-acid protein that contains a DNA-binding motif known as the HMG domain (10). This is essential for developing and differentiating various cell lines. SOX10 dysfunction hinders NC into olfactory ensheathing cells (OECs), melanocytes, intestinal ganglion cells, and numerous autonomic and sensory ganglion cells, leading to various clinical manifestations. In melanocytes, SOX10, cooperating with PAX3, binds to the MITF promoter to activate MITF and then activates the expression of dopachrome tautomerase (Dct) and tyrosinase (Tyr), which play an important role in melanin synthesis (1, 11). Melanocyte dysfunction results in abnormal pigmentation of the hair, skin, and irises. Furthermore, melanocytes play a crucial role in inner ear homeostasis (12). SOX10 is expressed in the otic vesicle, restricted to the epithelium and glial cells in the mouse inner ear (13, 14). This is consistent with our patient's sensorineural hearing loss and the observed semicircular canal abnormalities, as recent studies have reported hypoplasia/dysplasia or agenesis of the semicircular canals in patients with SOX10 mutations (15). SOX10 also plays a critical role in OECs, which are essential for the development of the olfactory bulb and the migration of GnRH cells (16). The patient's anosmia and HH are directly linked to SOX10's role in these processes. In mice with a SOX10 mutation, OECs were nearly absent, and they displayed de-fasciculation and misrouting of nerve fibers, as well as impaired migration of GnRH cells (2).

SOX10 mutations may be a common pathogenic factor in KS and WS. In a study cohort of 17 previously reported KS patients with SOX10 rare sequence variants (RSVs), 13/17 had ≥ 1 WS-associated feature(s) (17). Furthermore, in a few previously reported WS patients with SOX10, KS phenotypes existed. However, KS characteristics are always underestimated unless individuals are followed up to adolescence or through stimulation tests with GnRH. The KS is an anosmic form of idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (IHH). Identical RSVs were identified in cases independently ascertained by KS or WS. Combining the shared mutational spectrum, mutational mechanisms, and overlapping alleles, the IHH-WS phenotypic continuum hypothesis has been substantiated (17). This concept highlights that WS and KS, when caused by SOX10 mutations, represent a spectrum of clinical manifestations rather than distinct disorders. For instance, identical RSVs have been identified in cases independently ascertained for KS or WS (17). Recognizing co-segregating phenotypes is vital to prevent delayed recognition and treatment. In one report, a female infant with SOX10-related WS eventually presented with IHH during a longitudinal follow-up (18).

This case represents the reported instance of SOX10-related KS and WS2 co-occurrence, enriching the understanding of this rare phenotypic overlap. A comparative summary of previous reports, including the present patient, is provided in Table 2. This comparison highlights both the shared features, such as sensorineural hearing loss, pigmentary abnormalities, anosmia, and HH, and the genetic heterogeneity, with various types of SOX10 mutations implicated. The consistent involvement of the HMG domain across these cases underscores its critical role in the pathogenesis of both phenotypes. The rarity of reported cases may also suggest potential underdiagnosis of KS features in WS patients, especially given that hypogonadism often manifests later in adolescence and requires specific endocrine evaluation.

| Features | Present Case | Chen et al. (6) | Wakabayashi et al. (16) | Hamada et al. (19) | Graziani et al. Proposita (III-2) (20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient age/sex | 15-year-old male | 28-year-old male | 17-year-old male | 14.9-year-old female | 28-year-old female |

| Primary WS phenotype | Sensorineural hearing loss, blue iris | Bilateral sensorineural deafness, blue irises, white forehead hair | Hearing impairment, hypopigmented iris | Bilateral iris depigmentation, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, hirschsprung disease (WS4C) | Mild bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, pigmentation abnormalities (multiple freckles, patchy heterochromia of scalp hair) |

| Primary KS phenotype | HH, anosmia, testicular hypoplasia | Hypogonadism, hyposmia | Anosmia, delayed puberty, HH | HH, anosmia | HH, anosmia, olfactory bulb agenesis |

| SOX10 mutation | c.433_c.435delCTG, p.L145del | c.1179_1180insACTATGGCTCAGCCTTCCCC, p.Ser394fs | c.373C>T, p.Glu125X | c.124delC, p.Leu42Cysfs*67 | c.506C>T, p.Pro169Leu |

| Mutation type | In-frame deletion | Frameshift | Nonsense | Frameshift | Missense |

| HMG domain involvement | Yes (exon 3) | No (outside HMG domain) | Yes (exon 3) | Yes (exon 3) | Yes (C-terminal distal part of HMG domain) |

| Inheritance pattern | De novo heterozygous | De novo heterozygous | Sporadic | Novel (sporadic) | Inherited (from mother) |

| Key outcomes/management | Hearing aids, hormone replacement therapy | hCG/hMG treatment, increased testosterone and testicular volume | Testosterone-replacement therapy | None | Hormone replacement therapy, menarche induced, later osteoporosis/hypoadrenalism treated |

| Other features | Semicircular canal abnormalities | Obesity, pituitary hypothyroidism, subclinical hypothyroidism, insulin resistance | Aplastic olfactory bulb, subclinical hypothyroidism | None | Pituitary hypoplasia, secondary hypoadrenalism, osteoporosis |

Abbreviations: WS, Waardenburg syndrome; KS, Kallmann syndrome; HH, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism; HMG, high-mobility group; hCC, human chorionic gonadotropin.

Regarding treatment, supportive techniques (such as hearing aids) are commonly used. However, there is currently no cure for WS. It is important to note that cochlear implantation is a well-established therapeutic option for individuals with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss in WS2. But in this specific case, the patient's hearing loss was effectively managed with conventional hearing aids. For pigmentary changes, dermatologic care is primarily cosmetic and supportive, but treatments reported in the existing literature for patients do not address the treatment of pigmentary changes. This aspect may require more attention in the future. Gene delivery and stem cell replacement therapies remain in the preclinical stages of research using genetic animal models (21). Some patients may experience an increase in testicular volume through early hormone replacement therapy. A case report highlighted the first patient with reversible congenital HH associated with SOX10-related KS (22). However, this patient's olfactory bulb and semicircular canals remained hypoplastic. With early and timely diagnosis, along with appropriate hormone replacement therapy, patients may develop secondary sexual characteristics, maintain normal sex hormone levels, and potentially restore fertility.

SOX10 is located in 22q13.1 and contains 5 exons. Exons 1 and 2 are non-coding exons. The start codon was in exon 3, and the stop codon was in exon 5. The HMG domain is critical for the pathogenesis of both phenotypes. Studies have shown that most missense variants were deleterious (23). Using in silico prediction algorithms, almost all HMG-domain missense variants are likely to be pathogenic. In this case, the novel mutation is in the HMG domain and exon 3, resulting in p.L145del and a series of code changes downstream. We predicted the structures of these proteins. The mutation caused a disturbing change in the protein. Specifically, our in silico predictions using I-TASSER and PyMOL indicate that the c.433_c.435delCTG (p.L145del) mutation, located within the critical HMG domain, results in a significant disruption of the protein’s tertiary structure. This structural alteration is expected to impair the protein’s ability to effectively bind DNA or interact with co-factors, thereby compromising its transcriptional regulatory activity. This likely leads to a loss-of-function effect, potentially through haploinsufficiency or nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (23), as previously suggested (19). Lin et al. (24) created a mutation of SOX10 in pigs, causing a premature stop codon in exon 3, and the pig had a highly similar phenotype of WS type II.

Genetic counseling was provided to the patient's family. Given the de novo nature of the SOX10 mutation, confirmed by trio-WES and Sanger sequencing, the recurrence risk for future offspring of the unaffected parents is considered very low. While the theoretical possibility of extremely low-level parental germline mosaicism cannot be entirely ruled out, it is generally considered negligible for reproductive planning in such de novo cases. For the patient himself, as an affected individual, there is a 50% chance of transmitting the mutation to his future offspring. These implications were thoroughly discussed with the family.

The wide clinical variation in SOX10 mutations may be due to the differential gradients of transcriptional activity, but this requires further investigation. While our in-silico predictions strongly suggest a disruptive impact of the p.L145del mutation on SOX10 protein function, future in vitro studies (e.g., luciferase reporter assays to assess transcriptional activity, protein stability assays) or in vivo studies (e.g., using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells or animal models) are crucial to definitively confirm the functional consequences of this novel mutation and further elucidate the precise pathogenic mechanisms.

3.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, we reported a novel heterozygous variant in exon 3 of SOX10, resulting in a series of downstream code changes. This finding supports the notion that SOX10 mutations may be a common KS and WS pathogenic factor. Recognition of co-segregating phenotypes is of particular importance for early diagnosis. This case highlights the need for clinicians to actively screen for KS features (anosmia, delayed puberty) in patients diagnosed with WS, especially those with SOX10 mutations. Conversely, patients presenting with KS should also be evaluated for hearing loss and pigmentary abnormalities (suggestive of WS). This reciprocal screening approach is crucial for early and comprehensive diagnosis and timely intervention, thereby improving patients’ long-term prognosis.

Further studies are needed to investigate the relationship between mutation location, mutation type, and phenotype in SOX10. Ongoing genotype-phenotype correlation studies and experimental functional validation of SOX10 mutations will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the SOX10-mediated disease spectrum.