1. Background

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infects over half of the global population, with particularly high prevalence in developing regions (1). In the northwest of China, meta-analyses report pediatric Hp infection rates of 42 - 58%, exceeding the national average (35 - 40%) (2, 3). This endemic burden, combined with documented iron/Vitamin D deficiencies in local Hp-infected children, underscores the clinical relevance of our investigation into symptom-specific nutritional impacts (4). Evidence has indicated a correlation between malabsorption of essential nutrients and Hp infection (5). The absorption of vitamins, including B12, A, C, folic acid, and E, may be compromised by Hp infection, which can alter gastric pH. Furthermore, Hp infection is associated with iron‐deficiency anemia. In contrast, some researchers have proposed differing views, reporting no meaningful correlation between Hp infection and iron deficiency or anemia (6). Similarly, the relationship between Hp infection and weight gain remains controversial, with very limited evidence regarding the impact of Hp eradication on bone growth and weight gain in children (7).

2. Objectives

This research examined the nutritional status of pediatric patients with Hp infection, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, to ascertain the impact of Hp infection on children's growth, development, and nutritional status in the local area. Following Hp eradication, a one‐year follow‐up was conducted to reassess their nutritional status. The results are summarized below.

3. Methods

The sample size was calculated using a two-independent-sample mean comparison formula, with a significance level (α) of 0.05 (two-sided) and statistical power (1- β) of 80%. The formula n = 2σ² (Zα/2 + Zβ)²/(μ1 - μ2)² was applied. The calculation indicated a minimum requirement of 76 cases per cohort. Accounting for a 20% potential attrition rate, the target sample size was set at ≥ 90 cases per cohort. The parameters for the mean values (μ1, μ2) and standard deviation (σ) were based on a preliminary pilot study conducted at Baoding Hospital, Beijing Children’s Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University, which measured the same nutritional indicators in a smaller cohort of Hp-infected children.

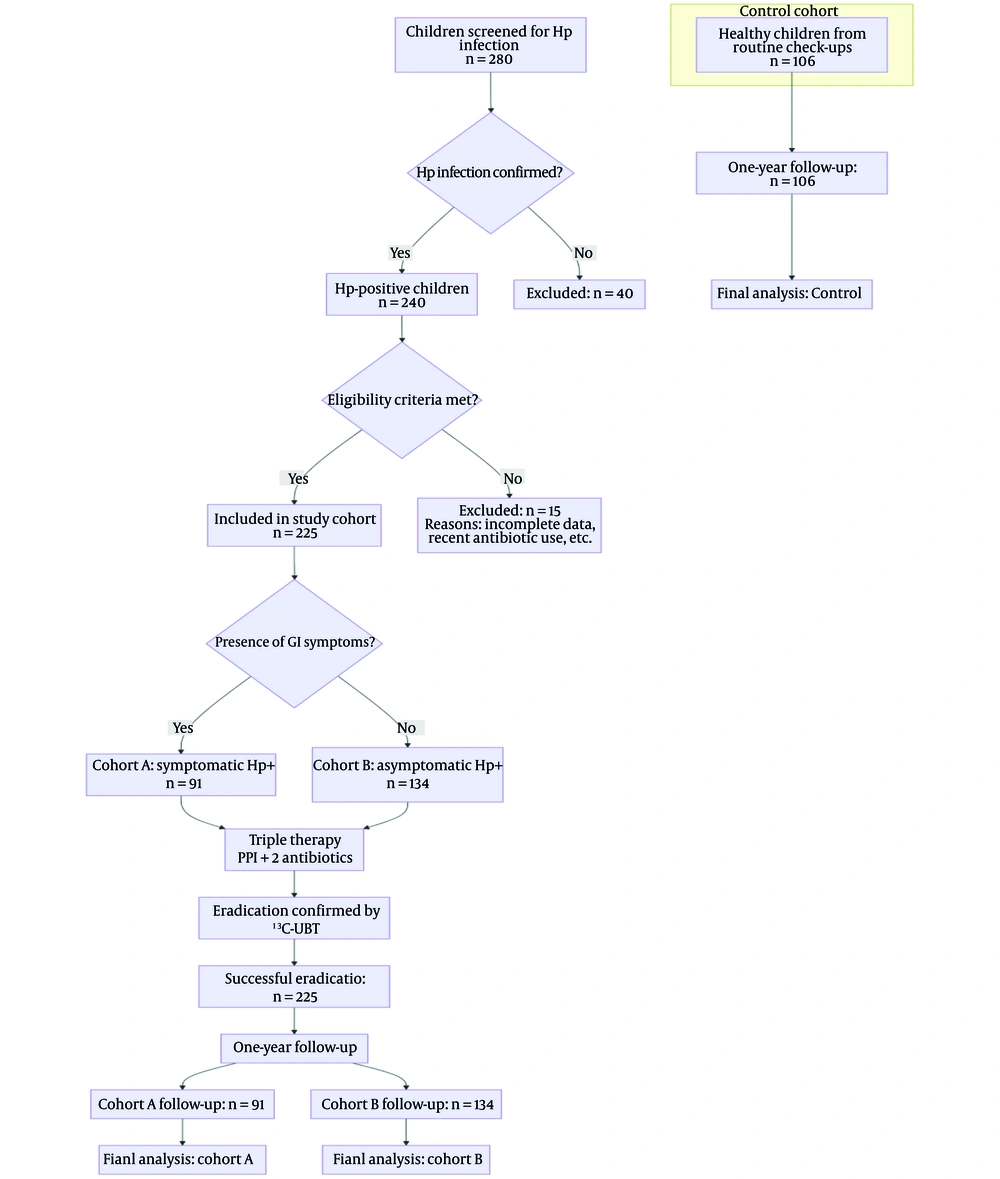

From May 2018 to May 2020, a total of 225 pediatric patients diagnosed with Hp infection at Baoding Hospital, Beijing Children’s Hospital affiliated to Capital Medical University and successfully treated with triple therapy were enrolled as the study cohort. The cohort included 123 males and 102 girls, with a mean age of 10.5 ± 2.8 years. The control cohort consisted of 106 healthy children who were recruited from those undergoing routine physical examinations at the hospital during the same period. All control subjects were rigorously screened to ensure they met the following criteria: (1) No history of chronic medical conditions (including cardiac, hepatic, renal, neurological, or hereditary metabolic diseases); (2) no acute infectious diseases within the previous month; (3) not taking any long-term medications or nutritional supplements; and (4) no gastrointestinal symptoms. Crucially, active Hp infection was definitively ruled out in all control participants using the ¹³C-urea breath test, with a negative result required for inclusion. This cohort consisted of 59 males and 47 females, with a mean age of 10.5 ± 2.8 years. The two cohorts did not exhibit any significant differences in age or sex distribution (P > 0.05).

Diagnostic Standards for Hp Infection: A positive result from the rapid urease test, endoscopic pathological staining, and/or the ¹³C‐urea breath test was used to diagnose Hp infection (8).

Eligibility criteria for selection: (1) Age ranging from 6 to 16 years; (2) absence of antibiotic or proton pump inhibitor use in the preceding month; (3) able to cooperate with comprehensive Hp infection testing; (4) able to complete a one‐year follow‐up.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of severe cardiac, hepatic, renal, neurological, or hereditary metabolic diseases; (2) acute infectious disease within the previous month's history; (3) use of nutritional supplements within the past six months.

Treatment regimen: All children diagnosed with Hp infection received triple therapy, consisting of an oral proton pump inhibitor and two antibiotics, primarily including amoxicillin, for two weeks. Four weeks after the treatment, a ¹³C‐urea breath test was performed to assess eradication efficacy. Throughout the entire study period, including the one-year follow-up after successful eradication, all children were instructed not to take any iron supplements, vitamin D supplements, multivitamins, or other medications that could directly influence the measured nutritional parameters. Details of the procedures for screening, grouping, and follow-up of the children are provided in Figure 1.

Sample collection: A 6 mL sample of fasting venous blood was collected in the morning from all participants.

Height and weight measurement: Height and weight were measured under the same conditions for all enrolled children, in the morning after voiding and defecation, and before breakfast.

Nutritional marker measurement: For children with Hp infection, nutritional markers were assessed prior to the commencement of treatment and at the one-year follow-up. Testing for the control cohort was implemented once only at the time of enrollment (baseline). The Abbott i2000 chemiluminescence analyzer and reagents supplied by Abbott were employed to ascertain serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 [25-(OH)D3] content. The Mindray BC-5300 automatic hematology analyzer was employed to measure hemoglobin (Hb). The BECKMAN COULTER AU5800 biochemical analyzer was employed to detect the levels of serum iron (SI), serum ferritin (SF), and prealbumin (PA). Serum ferritin reagents were acquired from Abbott, while SI and PA reagents were obtained from BECKMAN COULTER. The Baoding Key Laboratory of Clinical Research on Children's Respiratory and Digestive Diseases conducted all laboratory analyses.

The interpretation of nutritional marker levels was based on established pediatric reference ranges. Serum 25-(OH)D3 levels were classified as sufficient (> 30 μg/L), insufficient (20 - 30 μg/L), or deficient (< 20 μg/L) according to the guidelines from the global consensus recommendations on prevention and management of nutritional rickets. Anemia was defined according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for age and sex, with Hb cut-offs ranging from 115 g/L for children under 12 years to 120 g/L for children aged 12 years and above. Serum ferritin levels below 15 μg/L were considered indicative of iron depletion (9). Prealbumin levels were interpreted using age-adjusted reference values provided by the reagent manufacturer (Beckman Coulter) and our institutional laboratory guidelines. Serum iron reference ranges were also based on age-specific norms from our clinical laboratory.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

The software SPSS25.0 was employed to conduct every analysis of statistics. The mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s) was used to represent the information obtained from the measurements. Variance analysis and t-tests were implemented to evaluate comparisons between cohorts. A P-value of less than 0.05 was utilized to define statistical meaning. To address the issue of multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni method was used to adjust the significance level (α = 0.05/number of comparisons). All reported P-values are the results after correction.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

Among the 225 pediatric patients with Hp infection, 91 presented with gastrointestinal symptoms and were diagnosed and treated at the hospital's Department of Gastroenterology. Patients were allocated to cohort A, including 51 males and 40 girls, with a mean age of 10.3 ± 3.2 years. The spectrum of gastrointestinal symptoms in this cohort was characterized by recurrent abdominal pain (74.7%, 68/91), nausea/vomiting (27.5%, 25/91), bloating (24.2%, 22/91), and regurgitation (11.0%, 10/91). Endoscopic evaluation, performed as part of the diagnostic workup for all symptomatic patients, revealed nodular gastritis in 60.4% (55/91), erythematous or friable mucosa in 31.9% (29/91), and normal appearance in 7.7% (7/91). No cases of peptic ulcer disease were identified. One hundred thirty-four individuals, diagnosed with Hp infection during regular health examinations at the hospital, had no gastrointestinal symptoms and were thus categorized into cohort B, including 72 males and 62 girls, with a mean age of 10.6 ± 2.5 years. No statistically meaningful variations in sex or age were observed among cohort A, cohort B, and the control cohort (all P > 0.05). Kindly refer to Table 1.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

b P-value derived from Pearson's chi-square test.

c P-value derived from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

4.2. Intercohort Comparison of Height, Weight, and Nutritional Markers Before Eradication Therapy

Before eradication therapy, in comparison to cohort B and the control cohort, cohort A exhibited significantly lower levels of 25-(OH)D3, Hb, PA, SI, and SF (P < 0.05, respectively). The effect sizes for these deficits in cohort A versus the control cohort were large (Cohen's d > 0.8), underscoring their clinical relevance (found in Supplementary Table S1). No significant differences were observed in height or weight among the three cohorts (all P > 0.05). Furthermore, the levels of 25‑(OH)D3, PA, SI, and SF did not differ significantly between cohort B and the control cohort (all P > 0.05). Refer to Table 2 for the primary statistical comparisons and Supplementary Table S1 for detailed effect sizes and confidence intervals.

| Parameters | Cohort A | Cohort B | Control Cohort | P‐Value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Height (cm) | 137.9 ± 19.0 | 139.2 ± 19.8 | 138.5 ± 19.8 | P > 0.05 |

| Weight (kg) | 38.0 ± 8.4 | 39.0 ± 10.5 | 39.4 ± 8.7 | P > 0.05 |

| 25‐(OH)D3 (ug/L) | 26.6 ± 5.9 | 33.4 ± 5.7 | 34.6 ± 5.6 | P < 0.05 |

| SI (μmoL/L) | 12.1 ± 2.6 | 14.1 ± 2.3 | 14.6 ± 2.4 | P < 0.05 |

| SF (μg/L) | 21.9 ± 6.4 | 27.5 ± 7.2 | 28.6 ± 5.9 | P < 0.05 |

| Hb (g/L) | 121.1 ± 6.0 | 132.8 ± 7.0 | 134.0 ± 7.1 | P < 0.05 |

| PA (mg/L) | 151.7 ± 20.7 | 180.8 ± 23.5 | 184.5 ± 23.9 | P < 0.05 |

Abbreviations: 25-(OH)D3, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3; SI, serum iron; SF, serum ferritin; Hb, hemoglobin; PA, Prealbumin.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

b P-values derived from independent samples t-test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

4.3. Intercohort Comparison of Nutritional Markers at One‐Year Follow‐up

At one‐year follow‐up, the three cohorts exhibited no meaningful variations in the levels of 25‐(OH)D3, Hb, PA, SI, or SF (all P > 0.05). Refer to Table 3.

| Parameters | Cohort A | Cohort B | Control Cohort | P‐Value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25‐(OH)D3 (ug/L) | 33.1 ± 5.8 | 33.7 ± 5.8 | 34.6 ± 5.6 | P > 0.05 |

| SI (μmoL/L) | 14.1 ± 2.4 | 14.3 ± 1.9 | 14.6 ± 2.4 | P > 0.05 |

| SF (μg/L) | 27.0 ± 6.7 | 27.8 ± 6.5 | 28.6 ± 5.9 | P > 0.05 |

| Hb (g/L) | 132.2 ± 6.3 | 133.2 ± 6.2 | 134.0 ± 7.1 | P > 0.05 |

| PA (mg/L) | 181.7 ± 23.7 | 181.3 ± 26.6 | 184.5 ± 23.9 | P > 0.05 |

Abbreviations: 25-(OH)D3, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3; SI, serum iron; SF, serum ferritin; Hb, hemoglobin; PA, Prealbumin.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

b P-value derived from one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

4.4. Validation of Efficacy

A post-hoc power analysis, based on the observed effect sizes in our study population, confirmed that the achieved statistical power for detecting the primary outcome differences exceeded 95%, which is well above the conventional 80% threshold.

5. Discussion

Helicobacter pylori infection continues to be a significant public health issue in underdeveloped nations (10). It is linked to more than 75% of duodenal ulcer instances and 17% of stomach ulcer occurrences (11). Previous studies have generally suggested that Hp infection interferes with the absorption of essential nutrients and may negatively impact children’s growth and development (12). However, more recent research has indicated that Hp may also confer certain benefits or have potentially positive effects on the human body (13). To ascertain the impact of Hp infection on development and nutritional condition in children and whether the nutritional status of Hp ‐infected children improves following the standard triple therapy for Hp eradication, this study conducted a systematic analysis of height, weight, and the levels of 25‐(OH)D3, Hb, PA, SI, and SF in 225 pediatric patients with Hp infection and 106 healthy controls.

Our findings demonstrate that only Hp-infected children with gastrointestinal symptoms exhibited significant reductions in 25-(OH)D3, Hb, PA, SI, and SF levels compared to both asymptomatic carriers and uninfected controls, suggesting that symptomatic presentation is crucial in nutritional assessment. Furthermore, the large effect sizes (Cohen's d ranging from 1.04 to 1.87) for the nutritional deficits in symptomatic patients underscore a clinically meaningful impairment, likely contributing to functional outcomes such as fatigue, weakened immunity, and impaired cognitive development. The normalization of these nutritional markers — with effect sizes diminishing to negligible levels (Cohen's d < 0.2) — one year after successful eradication therapy demonstrates not only statistical reversal but also a robust clinical recovery. This suggests that eradicating Hp in symptomatic children can effectively resolve these clinically significant nutritional deficiencies, potentially mitigating their associated health risks. The absence of significant nutritional deficits in asymptomatic infected children (cohort B) may be attributed to potential factors such as a lower bacterial load, less virulent strains, or a state of immune tolerance resulting in reduced mucosal inflammation and minimal disruption to nutrient absorption (14, 15).

In addition, this study is inconsistent with some studies reporting no Hp-nutrition association, which may reflect methodological differences. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Russo et al. (as cited by Muhsen and Cohen) highlighted that only a minority of negative studies controlled for socioeconomic confounders (e.g., household income, dietary patterns) or stratified results by clinical symptom status (e.g., dyspepsia, anemia) (16). Indeed, unmeasured socioeconomic factors like household income and dietary patterns could confound the association. In our cohort, the inclusion of children from diverse backgrounds may have partly accounted for this (17). Ignoring these factors may obfuscate the true relationship between Hp infection and nutritional deficits.

Existing literature suggests that following Hp eradication, patients often exhibit a significant decrease in gastric pH, along with notable increases in body weight, serum total cholesterol, total protein, and albumin levels, as well as improved pancreatic function (18). Moreover, Hp eradication has been shown to effectively improve anemia and iron levels in patients with iron deficiency anemia, particularly in moderate to severe cases (19). In line with these findings, our study revealed that one year after successful Hp eradication using triple therapy, Hp‐infected children showed no significant differences in 25‐(OH)D3, Hb, PA, SI, and SF levels compared to healthy children. This is consistent with previous reports. One possible reason is that in children with gastrointestinal symptoms, Hp eradication helps promote the resolution of digestive symptoms, thereby facilitating a relatively rapid improvement in nutritional status.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the modest sample size may limit the statistical power and generalizability of our results. Future multi-center studies with larger cohorts are warranted to confirm these observations. Second, the absence of longitudinal anthropometric data (height and weight) in the control cohort precludes definitive conclusions regarding the long-term growth effects of Hp eradication. Subsequent investigations should incorporate standardized growth monitoring in both case and control cohorts to better elucidate this relationship. Finally, as a retrospective study, this study cannot completely exclude the effect of confounding on causal inference. Prospective studies are needed to establish temporality between Hp infection and nutritional changes. Despite the above limitations, this study provides important empirical data on nutritional differences in symptom stratification of Hp infection through rigorous laboratory testing and longitudinal follow-up.

5.1. Conclusions

In short, asymptomatic Hp infection alone does not affect children’s height, weight, or overall nutritional status. However, in Hp ‐infected children with gastrointestinal symptoms, the levels of 25‐(OH)D3, Hb, PA, SI, and SF tend to decline. After successful eradication therapy, symptomatic patients demonstrated normalization of these markers within one year, though the generalizability of this recovery timeline may require further prospective validation.