1. Background

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by skeletal muscle weakness. It is caused by antibodies targeting components of the neuromuscular junction, most commonly the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (AChR). The prevalence of MG varies by country and is increasing globally, particularly among women of reproductive age (1-3). The incidence in the general population ranges from 2.3 to 61.3 cases per million person-years, while in women of reproductive age it is estimated to be between 1:10,000 - 50,000. The most commonly affected muscle groups include the eyes, mouth, throat, proximal arms, and thighs, with characteristic muscle weakness that worsens throughout the day (1, 4, 5).

Although MG most commonly affects adult women of reproductive age, it may rarely manifest with clinical findings in newborns. Neonatal forms of myasthenia may include congenital myasthenic syndromes, which are autosomal recessive and persist throughout life, or transient neonatal myasthenia gravis (TNMG) (6, 7). Maternal anti-AChR antibodies can cross the placenta and cause TNMG. After birth, 10 - 20% of infants born to mothers with MG develop clinical signs of TNMG (3, 6, 8-10). These effects are independent of the severity of maternal disease or antibody titers (5, 10, 11). Clinical findings in affected neonates vary from weak cry, feeding difficulties, generalized hypotonia, facial diplegia or paresis to potentially life-threatening respiratory insufficiency. These symptoms typically appear within the first 72 hours of life and resolve completely in 90% of cases by 2 months of age as maternal antibodies are cleared from the infant (3, 4, 6, 8, 10-13). Treatment is mainly supportive and includes ventilatory and feeding support. In selected cases with severe or persistent symptoms, pyridostigmine can be administered (3).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to evaluate the clinical findings during pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in mothers diagnosed with MG.

3. Methods

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a tertiary university hospital with highly experienced perinatology and neonatology departments at Istanbul School of Medicine, Istanbul University to evaluate mothers who were diagnosed with MG prior to pregnancy and their infants. The hospital records of pregnant women who delivered over a 15-year period between January 2010 and January 2025 were reviewed retrospectively. Infants born before 34 weeks of gestation, those with major congenital anomalies, and neonates with perinatal asphyxia were excluded from the study. A total of 25 infants born to mothers diagnosed with MG who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Maternal clinical characteristics and neonatal data were obtained from hospital records. Clinical signs of TNMG were defined as hypotonia, weak cry, feeding difficulties, facial diplegia or paresis, and respiratory insufficiency. Maternal outcomes, including MG exacerbations during pregnancy and postpartum, as well as the clinical characteristics of infants who developed TNMG, were evaluated.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using the SPSS version 28.0 software. Descriptive statistical methods were used in the analysis. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to assess whether the data followed a normal distribution. Numerical variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean±standard deviation, while those not normally distributed were presented as median (min-max). Categorical variables were described using No. (%).

4. Results

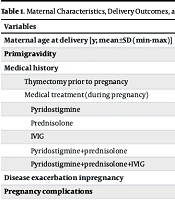

Among the 26,615 pregnancies followed over 15 years, 29 pregnant women were diagnosed with MG. The incidence of MG among pregnant women was found to be 10.9 per 10,000. Two of these mothers’ babies were excluded from the study due to a gestational age (GA) below 34 weeks, and two others were excluded because they were transferred to another hospital. The mean maternal age was 36.5 ± 6.7 (19 - 44) years, and 17 (68%) were primigravid. Thymectomy had been performed in 14 (56%) mothers at least two years before pregnancy. Twenty-one mothers (84%) were receiving medical treatment [prednisolone, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), pyridostigmine]. Two of the untreated mothers had a history of thymectomy. Twelve mothers (48%) continued medical treatment after undergoing thymectomy. The most common autoimmune disorder observed in mothers was autoimmune thyroid disease [n = 3 (12%)]. These mothers were on L-thyroxine therapy and remained euthyroid throughout pregnancy.

During pregnancy, MG symptoms worsened in 4 (16%), improved in 5 (20%), and remained stable in 16 (64%) of the mothers. The most common pregnancy-related complication was gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). Cesarean section was performed in 22 pregnancies (88%), and no assisted delivery interventions were required in vaginal births. In one mother with stable MG during pregnancy, a sudden onset of respiratory distress, hypoxemia, and aortic and mitral valve insufficiency was observed after cesarean delivery. The patient’s prednisolone dose was increased, and IVIG therapy was administered. Another mother experienced postpartum weakness and shortness of breath, requiring short-term monitoring in the intensive care unit, where she also received IVIG treatment. Maternal characteristics, delivery outcomes, and the clinical course of MG during pregnancy are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery [y; mean±SD (min-max)] | 36.5 ± 6.7 (19 - 44) |

| Primigravidity | 17 (68) |

| Medical history | |

| Thymectomy prior to pregnancy | 14 (56) |

| Medical treatment (during pregnancy) | 21 (84) |

| Pyridostigmine | 11 (52.3) |

| Prednisolone | 5 (23.8) |

| IVIG | 1 (4.76) |

| Pyridostigmine+prednisolone | 2 (9.52) |

| Pyridostigmine+prednisolone+IVIG | 2 (9.52) |

| Disease exacerbation inpregnancy | 4 (16) |

| Pregnancy complications | |

| GDM | 4 (16) |

| Preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (≥ 18 hours) | 2 (8) |

| Hypertension | 2 (8) |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis | 1 (4) |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Caesarean section | 22 (88) |

| Vaginal | 3 (12) |

| Postpartum exacerbation | 2 (8) |

Abbreviations: GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Of the 25 pregnancies, 2 resulted in late preterm births (at 35 + 3/7 and 36 + 4/7 weeks). The mean GA of the newborns was 38.41 ± 1 (35 + 3/7 – 40 + 3/7) weeks, and the mean birth weight was 3088 ± 512 grams (2000 - 4030). Fifteen (60%) newborns were female. Three infants (12%) were small for GA, while two (8%) were large for GA. None of the newborns required resuscitation in the delivery room.

All infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. Two newborns developed respiratory distress after birth and were supported with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in the delivery room. One of them required invasive mechanical ventilation due to worsening respiratory distress. Another infant, who was normal after birth, developed respiratory distress at the second hour of life and needed CPAP. Transient tachypnea of the newborn and congenital pneumonia/sepsis were excluded by chest radiography and laboratory examinations for all three infants.

Among the three infants diagnosed with TNMG, one presented with respiratory distress and generalized hypotonia starting in the delivery room. The infant exhibited weak sucking, hypersalivation, and swallowing difficulties. As these symptoms became more pronounced by the fourth hour of life, the infant was intubated. Pyridostigmine treatment was started at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/dose every 6 hours. At the 12th hour of treatment, sinus bradycardia developed, leading to an extension of the dosing interval to every 8 hours, after which no further bradycardia episodes occurred. By the second day of treatment, TNMG symptoms began to improve; muscle tone increased, and the infant was extubated. Swallowing improved, and hypersalivation resolved. After 42 hours of life, respiratory support was no longer needed, and pyridostigmine therapy was completed over 10 days.

The second infant with TNMG required CPAP support for 22 hours. Respiratory distress improved and there were no significant hypotonia or swallowing difficulties, so anticholinesterase treatment was not administered. The third infant diagnosed with TNMG was normal immediately after birth; however, at the sixth hour of hospitalization, mild respiratory distress was observed. The infant was followed on CPAP and no longer required respiratory support after 4 hours. Both infants remained symptom-free until discharge. The median length of neonatal hospital stay was 3 (3 - 15) days. No neonatal deaths occurred. Neonatal outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Girls | 15 (60) |

| Boys | 10 (40) |

| GA (wk) | 38.41 ± 1 (35 + 3/7 - 40 + 3/7) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3088 ± 512 (2000 - 4030) |

| Weight for GA | |

| Small for GA | 3 (12) |

| Large for GA | 2 (8) |

| Resuscitation in the delivery room | 0 |

| Perinatal asphyxia | 0 |

| Apgar scores (mean±SD) | |

| 1st minute | 8.52 ± 0.77 |

| 5th minute | 9.28 ± 0.46 |

| Symptoms related with TNMG (n = 3) | |

| Respiratory problems | 3 (100) |

| Invasive ventilatory support | 1 (33.3) |

| Non-invasive ventilatory support | 2 (66.7) |

| Feeding problems | 1 (33.3) |

| General hypotonia | 1 (33.3) |

| Pyridostigmine treatment | 1 (33.3) |

| Hospitalization for observation | 25 (100) |

| Duration of hospitalization [d; median (range)] | 3 (3 - 15) |

Abbreviations: GA, gestational age; TNMG, transient neonatal myasthenia gravis.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean±SD (range) unless otherwise indicated.

Among the three infants with TNMG symptoms, one of their mothers (33.3%) had a history of thymectomy. All three mothers were receiving medical treatment. The infant who received pyridostigmine treatment due to postnatal symptoms was born to a mother who had not undergone thymectomy. The mother of the infant who required 22 hours of CPAP support had undergone thymectomy and was under pyridostigmine treatment. The mother of the infant who needed CPAP support for a short time had no history of thymectomy, was receiving corticosteroid therapy, and was hospitalized in the neurology department postpartum due to worsening clinical symptoms, where she received IVIG treatment.

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the outcomes of mothers with MG and their infants, followed over a 15-year period at a tertiary referral center. The incidence of MG among pregnant women was found to be higher than reported in the literature, while the rate of neonatal involvement was comparable to existing data (1, 4, 5). Myasthenia gravis may coexist with other autoimmune disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, autoimmune thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis-polymyositis, and Addison’s disease. In the study group, the most common coexisting autoimmune disorder among the mothers was autoimmune thyroid disease, in correlation with the literature (10, 14, 15).

Cholinesterase inhibitors are the main drugs used in the treatment of MG. Intravenous administration of these drugs is not recommended during pregnancy except in life-threatening emergencies, because they may induce uterine contractions (13). Corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and IVIG can be safely used throughout pregnancy. However, immunosuppressive agents such as mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and azathioprine should be used with caution (16). Thymectomy is another treatment option when medical therapy fails. In the study group, more than half of the patients had undergone thymectomy prior to pregnancy, and 84% of the patients were receiving single or multiple medications.

The clinical course of MG during pregnancy is variable. Myasthenia gravis symptoms remain stable in 30 - 59% of pregnancies, worsen in 19 - 50%, and improve in approximately 20% (17-23). The rate of disease exacerbation in our study group was found to be significantly lower than reported in the literature. This lower exacerbation rate may be attributed to long disease duration, close monitoring through a multidisciplinary approach, and adherence to medications.

Vaginal delivery is reported to be the major route of delivery among mothers with MG (15, 19, 24). In our study group, cesarean section rates were higher than reported. This may be attributed to additional risk factors such as breech presentation, macrosomia, repeated cesarean sections, and arrested labor. Most studies evaluating pregnancy complications in women with MG reported similar rates of cesarean delivery, prematurity, and pregnancy complications to the general population (23, 25). However, some studies have reported increased risks of GDM and premature rupture of membranes (5, 20, 21). In our study, the most common pregnancy complication was GDM.

The TNMG has two clinical forms. Poor sucking and generalized hypotonia are the main clinical findings of the typical form. Swallowing abnormalities, respiratory distress, and weak cry are other characteristic features of typical TNMG. Severe forms of this transient condition often require mechanical ventilation (16, 22). The atypical form is less common and is mostly seen as fetal arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (16). After the removal of blocking antibodies from the blood and muscle tissues, the infant recovers and regains normal strength. Complete recovery occurs within 2 months in 90% of cases. Some studies have identified young maternal age as a risk factor for TNMG (21). The median age of mothers who developed TNMG in our cohort, 36 years, was higher than reported in the literature.

The diagnosis of TNMG can be made based on suspicious clinical findings and maternal history. In the absence of maternal history, diagnosis can be supported by testing for anti-AChR antibodies, administration of a test dose of cholinesterase inhibitors, or electromyography. If there is no response to the initial test dose, it can be repeated 4 hours later. For mild TNMG symptoms, close monitoring and small, frequent feedings are needed. In severe cases, cholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine or pyridostigmine are the primary treatments. When using intramuscular cholinesterase inhibitors, especially at high doses, a cholinergic crisis may occur, characterized by abdominal cramps, sudden diarrhea, cardiac arrhythmias, or bronchial obstruction due to increased bronchial secretions. Atropine should be available to counteract these symptoms. Generally, neonates with TNMG require cholinesterase inhibitors only for a few days until swallowing ability is restored. Intravenous neostigmine is contraindicated in infants under 2 years of age due to the risk of potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation. Certain drugs, like aminoglycosides, may exacerbate myasthenic symptoms and should be avoided in this patient group (6, 16, 26). In our case, no adverse effects were observed following the initial test dose; however, sinus bradycardia developed at the 12th hour of treatment. After the dosing interval was extended, no further episodes of bradycardia occurred. Clinical improvement began by the second day of treatment, and by 42 hours of life, respiratory support was no longer required.

The incidence of TNMG has been reported between 2.5% and 35%, increasing due to greater awareness of MG and its effects on neonates (15, 27-30). The TNMG incidence in our study was similar to that reported in the literature. No studies have shown a strong correlation between maternal disease severity or maternal antibody titers with the severity of TNMG (5, 10, 11). All women with any type of autoantibody-positive MG may deliver an affected newborn. Prior thymectomy history and longer disease duration have been reported as protective factors (15). Although TNMG is a self-limiting and transient condition, it can present with life-threatening symptoms. Due to transplacental passage of maternal medications, early signs of TNMG can be masked at birth. Therefore, even if no signs are observed at the first examination, all infants born to mothers with MG should be closely monitored in the neonatal intensive care unit, especially during the first 72 hours of life (3, 4, 6, 8, 10-13).

The main limitation of the study is its retrospective design, which resulted in incomplete maternal data such as the time elapsed from MG diagnosis, thymectomy time, and maternal antibody status.

5.1. Conclusions

Although TNMG is uncommon in the newborn population, it can have a catastrophic outcome. Clinical presentations can vary from mild hypotonia or transient poor sucking to serious respiratory failure. Mild forms can be managed with careful surveillance, but severe forms may need aggressive ventilatory and nutritional support. Clinicians should be alert to the emerging signs and symptoms of the baby through serial examinations.