1. Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was initially believed to represent a developmental delay in childhood behavioral control that typically resolves by adulthood (1). However, several studies have established that ADHD is a disorder that may persist into adulthood (2, 3). Epidemiological studies have indicated that ADHD is a common condition, affecting 5 - 7% of school-age children. It is estimated that 2 - 4% of adults are affected, with an estimated persistence rate of 50% to 70% into adulthood (4, 5).

Previous reports of adult ADHD prevalence among workers aged 18 - 44 in the United States, based on DSM-IV criteria, indicated a prevalence rate of 4.2%. The prevalence was 4.9% in men and 3.3% in women. Additionally, the prevalence rates were 3.4% and 4.7% among the 18 - 29 and 30 - 44 age groups, respectively (4). The prevalence rate of adult ADHD among the general adult population of Tabriz citizens has been estimated at 3.8% (6). Despite significant prevalence, various studies have reported a growing trend of ADHD in adults from 2007 to 2016 across different American racial groups (7). Owing to the significant prevalence of adult ADHD and its substantial economic and social impacts, accurate diagnosis and screening are essential first steps to reduce its financial burden on the country’s economy (8-11).

In the initial phase of disease management, gathering prevalence statistics and conducting valid screening of high-risk individuals are the most important objectives for policymakers and health managers (12). However, considering the geographic distribution of communities, limited access to psychiatrists in some areas, and the high economic costs of psychiatric consultations, adopting new screening methods such as internet-based and online screening can help develop social health infrastructure and reduce program costs (12-14).

Internet questionnaires offer several advantages over paper-based questionnaires, potentially leading to qualitative and quantitative improvements in survey research (14). These online questionnaires are now widely used, with various strategies employed to achieve acceptable participation rates (15). Reviews of online surveys in psychiatry indicate that online surveys can be both useful and practical. A study in Ireland on screening for depression and anxiety in adults with cystic fibrosis found no significant difference in the mean scores or prevalence estimates between online and paper psychiatric questionnaires (16). The demographic characteristics of participants may reflect greater health needs among these individuals, and online screening can help reduce the overall demand for specialized health services and decrease the burden of economic costs (17).

Although most adult ADHD screening studies have utilized paper-based formats, relatively few online surveys have been conducted (18, 19). However, the limited available reports suggest similar prevalence estimates for adult ADHD using online and paper surveys. A United States study using the Mturk website for online screening of adult ADHD found a prevalence of 4.5% among participants (18).

2. Objectives

Accordingly, the present study, while emphasizing the importance of online surveys for psychiatric disorder screening, also explores key aspects of online survey feasibility in the Iranian-Tabriz community. The study considers participation level, estimated prevalence of adult ADHD, comparison with standard criteria (DSM-5), and results from previous paper-based surveys in Tabriz (6). Based on this, the present study aimed to assess the prevalence of adult ADHD in Tabriz, Iran, using online screening and clinical diagnosis.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

The present study is a descriptive-cross-sectional study conducted online. The target population comprised all outpatients referred to Asadabadi Hospital in Tabriz during the second half of 2018. Tabriz is the capital of East Azarbaijan province in northwestern Iran. According to the Statistics Center of Iran, Tabriz has a population of approximately 1.6 million. The city is served by 20 governmental and eight non-governmental hospitals. Asadabadi Hospital, affiliated with Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, is a referral hospital representing the general population, located in a densely populated and economically average area. The hospital provides outpatient clinical and care services, including a psychiatric ward dedicated to outpatient care. According to hospital records from 2018, a total of 135,610 outpatients visited the hospital during the six months under study, with 2,687 referred to the psychiatric clinic.

Given the study’s objective of online ADHD screening, the study population was invited using banners and public advertisements placed at the hospital entrance and clinical wards, inviting all outpatients to participate in the online ADHD evaluation. Banners and advertisements remained in place for six months in designated public areas.

Inclusion criteria were willingness to participate, willingness to undergo an interview in the subsequent step, literacy enabling e-participation, and being at least 18 years old. Participants who did not complete all online questions, used identical IP addresses, or answered the research questions multiple times were excluded.

3.2. Research Tools

3.2.1. Demographic Questionnaire

This questionnaire collected information on age, gender, and family history of ADHD.

3.2.2. Adult Conners Self-Reporting Scale

The Adult Conners Self-Reporting Scale (CAAS-S: SV) is a validated tool for screening for ADHD in adults based on DSM-IV criteria. This scale contains 30 items and four subscales: Attention Deficit Index (subscale A), Hyperactivity-Impulsivity Index (subscale B), ADHD Symptoms Total Index (subscale C), and ADHD Index (subscale D). The overall score provides an ADHD screening score. In this study, the ADHD Index (subscale D) was used to screen for ADHD (20). Respondents rate themselves on a 4-point scale (0 = never to 4 = very frequently), with total scores for the 30 items ranging from 0 to 120. Individuals with scores above 16 on subscale D were identified as potential ADHD cases. The scale was translated into Persian and back-translated by Sadeghi-Bazargani et al. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.83 to 0.97, and validity assessed by ROC curve was 0.88 (20).

3.2.3. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID) is a structured interview based on DSM-IV and has two main versions: SCID-I for major psychiatric disorders (axis I) and SCID-II for personality disorders (axis II). The SCID implementation requires a psychiatrist’s clinical judgment. In most diagnoses, reliability is above 0.85, and in half, it is above 0.9, indicating satisfactory reliability. The Persian version of the SCID is validated for clinical and research use. In this study, the SCID was used to diagnose psychiatric disorders (21).

3.2.4. Wender Utah Rating Scale

This self-report questionnaire has six subscales (dysthymia, oppositional defiant disorder, schoolwork problems, conduct disorder, anxiety, and ADHD). Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS) contains 25 items related to ADHD, used to retrospectively diagnose childhood ADHD in individuals aged 18 years and above. Ratings are on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all or very slightly; 1 = mildly; 2 = moderately; 3 = quite a bit; 4 = very much), with scores for the 25 ADHD items ranging from 0 to 100 (cut-off score 46). The scale is widely used, with favorable reliability and validity (22, 23).

A psychiatric diagnostic interview by a psychiatrist, using DSM-5 and Utah criteria, was employed for definitive diagnosis of adult ADHD, childhood ADHD, and persistence into adulthood. All psychiatric interviews were conducted by trained psychiatrists blinded to participants’ online screening results [Conners Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scales (CAARS-S) and WURS] to minimize potential assessment bias. Besides diagnosing adult ADHD, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV) was used to assess comorbid axis I disorders — including major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and other psychiatric conditions — to ensure comprehensive clinical evaluation.

3.3. Procedure

The study was conducted with the necessary permits and coordination from Asadabadi Hospital. Banners and public advertisements were designed and positioned in prominent locations to attract patient attention. These remained in place for six months.

A dedicated website (https://www.mentaltest.ir/), designed by an experienced web designer, introduced the research project, outlined objectives, detailed ethical considerations, and obtained informed consent. By clicking a research icon, participants accessed a second page containing the demographic characteristics questionnaire and the CAAS-S: SV. All data were stored online and accessible only via the server. The website was active for six months concurrent with the survey.

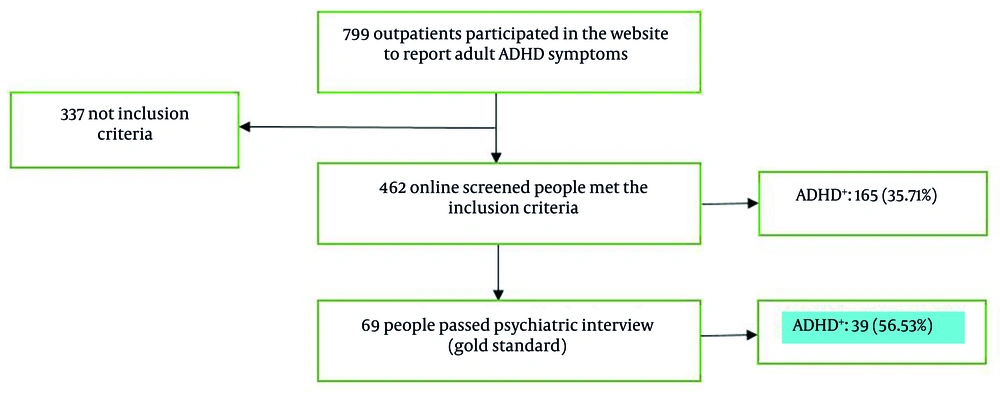

Of 2,687 outpatients referred to the psychiatry clinic during the study period, 799 participated in the online ADHD symptoms survey. Data were checked for IP duplication and completeness. Three individuals were excluded due to duplicate IPs, and 334 were excluded for incomplete questionnaires, resulting in 462 eligible participants. The participation rate for online screening was 57.82% (462/799). All 462 who met inclusion criteria were contacted for the next phase. Of these, 69 voluntarily attended the psychiatric clinical interview (using SCID) to compare outcome measures between online screening and the gold standard interview.

Given the descriptive and exploratory nature of the study, the sample size was determined pragmatically, including all outpatients willing to participate during the six-month period. Future studies may calculate sample size based on expected prevalence and diagnostic accuracy.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

All raw questionnaire scores and subscale scores were converted to a standardized 0 - 100 scale to facilitate direct comparison and interpretation. These transformed scores were used for descriptive analyses and statistical comparisons.

SPSS software (version 21.0, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were calculated for ADHD prevalence. Parametric tests [independent t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)] and non-parametric tests (Fisher’s exact test, chi-square) were used to examine associations between ADHD and independent variables (age group, gender, ADHD history, and psychiatric comorbidity). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

The mean ± SD age of participants was 32.94 ± 9.27 years. The majority were women aged 19 - 29 years (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) | Comparison of the Average D-Index of the Conners Questionnaire | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P-Value | ||

| Gender | t = 56; P = 0.11 a | ||

| Female | 293 (63.4) | 16.05 ± 9.28 | |

| Male | 169 (36.6) | 17.44 ± 8.86 | |

| Age (y) | F = 3.54; P = 0.01 b | ||

| 19 - 29 | 189 (40.9) | 18.01 ± 9.46 | |

| 30 - 39 | 162 (35.1) | 14.87 ± 8.03 | |

| 40 - 49 | 86 (18.6) | 16.38 ± 9.71 | |

| 50 ≤ | 25 (5.4) | 17.15 ± 10.14 | |

a Independent t-test.

b One-way ANOVA

4.1. Prevalence Estimation of Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Of 462 individuals screened online, 165 screened positive for ADHD, yielding a prevalence of 35.71% among those completing the screening. Of 462 participants, 69 attended clinical assessment. Among those with a positive screening result, the prevalence of ADHD as determined by psychiatric diagnosis was 56.53% (39/69) (Figure 1). A comparison between participants who attended the psychiatric interview (n = 69) and those who did not (n = 393) showed no significant differences in age (P = 0.469), gender distribution (P = 0.138), or family history of ADHD (P = 0.312). This suggests that the interviewed subsample was broadly representative of the larger screened cohort.

Using the standardized scoring approach, mean D-Index scores from the Conners Questionnaire were converted to a 0 - 100 scale for comparison across demographic groups. The mean D-Index score was 17.44 ± 8.86 in men and 16.05 ± 9.28 in women, with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.11). The ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference across age groups (P = 0.01). Post-hoc Tukey comparisons indicated that the mean ADHD Index score was significantly higher in the 19 - 29 age group compared to the 30 - 39 group (P = 0.008). No other pairwise differences were statistically significant.

Fisher’s exact test and chi-square test assessing the association between age, sex, and ADHD in the psychiatric interview found no significant association between gender and ADHD, nor between age and ADHD (Table 2).

Abbreviation: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-square.

c Fisher’s exact test.

Table 3 indicates the association between ADHD and family history of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity among outpatients referred to interview. Twenty of 39 ADHD cases had a family history of ADHD, whereas only 2 of 30 non-ADHD cases had such a history. There was a significant association between ADHD and family history of ADHD (X2 = 15.54, P < 0.001).

| Variables | ADHD | No-ADHD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of ADHD | X2b = 15.54; P = 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 20 (51.3) | 2 (6.7) | |

| No | 19 (48.7) | 28 (93.3) | |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 0.213 | ||

| Yes | 19 (48.7) | 9 (30) | |

| No | 20 (51.3) | 21 (70) |

Abbreviation: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Fisher’s exact test.

There was no significant difference between ADHD and psychiatric comorbidity (P = 0.213). Table 4 shows that the sensitivity and specificity of the online screening were 84.61% and 66.67%, respectively. The positive predictive value (PPV) was 76.74%, and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 76.92%.

| Online Screening | Psychiatric Interview | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Positive | 33 | 10 | 43 |

| Negative | 6 | 20 | 26 |

| Total | 39 | 30 | 69 |

a Sensitivity: 33/39 = 84.61% [95% CI: 70.5 - 93.5]; Specificity: 20/30 = 66.67% [95% CI: 47.2 - 82.7]; PPV: 33/43 = 76.74%; NPV: 20/26 = 76.92%.

To further evaluate the screening questionnaire’s performance, standardized Conners’ D-Index scores (0 - 100 scale) were compared between participants clinically diagnosed with ADHD and those without ADHD during the psychiatric interview. As shown in Table 5, participants with clinically confirmed ADHD scored significantly higher (23.60 ± 8.90) than non-ADHD participants (11.40 ± 6.20), indicating that the online screening tool had clear discriminative validity (t = 5.98, P < 0.001).

| Group (Clinical Diagnosis) | No. | Mean ± SD of D-Index (0 - 100) | Test | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADHD | 39 | 23.60 ± 8.90 | t = 5.98 | < 0.001 |

| Non-ADHD | 30 | 11.40 ± 6.20 |

Abbreviation: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

5. Discussion

Research findings showed that the prevalence of adult ADHD based on the D-Scale cut point in the Conners Questionnaire via online screening was 35.71%, and the prevalence based on psychiatric interview was 56.53%. The higher prevalence in the online-screened population compared to the general population is likely because these individuals, having noticed ADHD symptoms (as described on banners), self-selected for the online screening. This finding is somewhat inconsistent with previous studies utilizing diagnostic interviews and samples collected for diagnosis (24, 25). Previous reports indicate that web-based samples tend to have higher ADHD Questionnaire scores, with approximately 40% scoring above the clinical cut-off. A meta-analysis of data from detention settings estimated the prevalence of Adult ADHD at 26.2% (24, 25). Given that the present study’s target population consisted of hospital and clinic attendees, including psychiatric clinics, the higher diagnostic prevalence may be attributable to differences in the statistical sample (24).

Our prevalence estimates are partially consistent with Hirsch et al. (25), who reported higher ADHD scores among women in web-based samples, emphasizing that online recruitment tends to attract individuals already aware of ADHD symptoms. Variations between studies may result from differences in recruitment strategies, cultural factors, and sample characteristics.

The online screening tool demonstrated a sensitivity of 84.61% and a specificity of 66.67% compared to the psychiatric interview. The moderate specificity (66.67%) indicates a considerable rate of false positives. While the tool is sensitive in detecting potential ADHD cases, some individuals who screen positive may not meet diagnostic criteria upon clinical evaluation. Therefore, in clinical practice, it is essential to follow up positive online screening results with comprehensive assessments, such as structured psychiatric interviews, to confirm diagnosis and avoid unnecessary labeling or interventions. Such steps help optimize resource use and enhance the accuracy of identifying true ADHD cases.

Unlike paper-based studies reporting higher ADHD rates in men (6, 26), the prevalence in this study was similar in men and women. Hirsch et al. also found that women scored significantly higher in web-based samples (25). Differences in the statistical population are likely the most important factor in divergent findings.

Although the mean D-Index score was higher in the 19 - 29-year age group, there was no difference in ADHD prevalence between age groups, consistent with previous Tabriz reports (6).

A higher family history of ADHD in the positive-screened group may be influenced not only by heredity but also by participants’ awareness and attitudes toward ADHD based on family experience. Previous research indicates a higher ADHD prevalence among individuals with a family history, highlighting the importance of genetic influences. The ADHD’s high heritability of 74% has motivated the search for susceptibility genes (27). There are strong familial links and neurobiological similarities between ADHD and various psychiatric comorbidities, which present challenges in ADHD management and treatment (28, 29).

The majority of participants were young women aged 19 - 29 years, consistent with previous research (30). However, regarding sex, this finding contradicts Hirsch et al., whose study comparing the CAARS-S found that women constituted 73.3% of the paper-based sample and 39.2% of the online sample (25). In Iran, women’s greater attention to physical and mental health and higher participation in health centers likely contribute to their increased involvement in health studies. Advantages of electronic questionnaires — such as speed, scope, ease, low cost, editability, and optimal data processing — suggest their future use in research and national screening.

Study findings should be interpreted in light of limitations. The present study was limited to 2018, general hospital outpatients, and the CAARS-S. Limited awareness regarding gender and age of hospital referrals restricted generalizability. One limitation is that clinical variables such as family history of ADHD and psychiatric comorbidities were not recorded during the online screening phase; therefore, their association with screening outcomes could only be evaluated in the clinical interview subsample. Additional limitations include small sample size, lack of active screening, and the hospital-based (rather than community-based) nature of the study. The low interview attendance rate (69/462, 15%) is another limitation. Although attrition analysis found no significant demographic or clinical differences between interviewees and non-interviewees, spectrum bias remains a concern. Interview participants may differ systematically in symptom severity or health awareness, affecting observed prevalence. Future studies should implement strategies to increase interview participation, such as reminders or incentives, and conduct community-based research to minimize selection bias. These limitations highlight the need for further research using various questionnaire tools, settings, and samples. Moreover, only basic demographic information (age, gender, family history of ADHD) was collected; additional characteristics such as education, socioeconomic status, or occupation were not included. Future studies should collect more detailed demographic and clinical data to improve descriptive analyses and generalizability.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study, by launching an online screening system, not only highlighted the importance and methodology of innovative study systems but also identified ADHD prevalence patterns among project participants. The online screening demonstrated acceptable diagnostic performance with high sensitivity (84.61%) and moderate specificity (66.67%), suggesting its potential as a preliminary tool for adult ADHD detection. These findings indicate that online screening can be implemented in various contexts and may provide a rapid, accessible instrument for healthcare providers, particularly as an effective method during epidemics such as the COVID-19 pandemic.