1. Background

In recent years, stalking and related behaviors have received considerable attention in both academic research and public discourse (1). Stalking is defined as a persistent pattern of unwanted and intrusive actions directed toward a specific individual. These actions may include repeated physical or visual proximity, unsolicited communication, verbal or written threats, and other behaviors that induce fear and emotional distress in the victim (2). The prevalence of stalking is concerning, with studies indicating that approximately one in six women and one in seventeen men report having experienced stalking during their lifetime (3). Such behaviors can result in serious psychological consequences, including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and diminished quality of life (4).

Obsessive relational intrusion (ORI) is a term introduced to describe a specific subset of stalking behaviors aimed at initiating or maintaining an intimate relationship with the target (1). Unlike general stalking, ORI is characterized by the pursuer’s desire for emotional closeness, which may not necessarily elicit fear or a sense of threat in the target. This distinction is important as it broadens the conceptualization of intrusive behavior to include actions that may be unwanted or inappropriate, even if not overtly threatening (5).

Examining ORI is essential for several reasons. First, it provides a nuanced understanding of relational dynamics and the spectrum of behaviors that constitute unhealthy relationship pursuit. Second, ORI can have notable psychological consequences for victims, such as increased relational rumination, emotional distress, and reduced life satisfaction (6, 7). Third, there is a pressing need for culturally appropriate and psychometrically sound tools to assess ORI across diverse populations. Existing instruments, such as the Stalking and Obsessive Relational Intrusions Questionnaire (SORI-Q), have been primarily validated in Western settings, raising concerns about their cross-cultural relevance and applicability (8, 9).

In this context, the Obsessive Relational Intrusion-Victim Short Form (ORI-VSF), developed by Spitzberg and Cupach in 2003 (6), offers a promising solution. The ORI-VSF is designed to assess the experiences of individuals who have been victims of ORI, shifting the focus from perpetrators to the lived realities of victims (10). It is conceptually grounded in relational goal pursuit (RGP) theory, which suggests that when individuals are obstructed from achieving relationship goals tied to their identity, they may engage in obsessive and intrusive behaviors (11). This scale conceptualizes victimization through two distinct but related factors: Pursuit and aggression. The pursuit dimension refers to persistent and unwanted behaviors aimed at initiating or maintaining a relationship, such as repeated texting or showing up uninvited. In contrast, the aggression dimension captures threatening or hostile behaviors, which may emerge when relational efforts are rejected or blocked. This two-factor model reflects the multifaceted nature of ORI and aligns with prior theoretical and empirical work by Spitzberg and Cupach (2014) as cited by Aslam et al., who emphasized the diversity of intrusive behaviors victims may experience (1).

The instrument’s conceptual clarity and strong content validity make it particularly valuable for research purposes. However, its cross-cultural applicability remains underexplored, as few validated versions exist in diverse cultural settings (9). As Brownhalls et al. (5) noted, many existing instruments fail to capture the full psychological and sociocultural complexity of ORI, limiting their ecological validity and clinical usefulness. Cultural values and societal norms play a pivotal role in shaping how ORI behaviors are experienced and interpreted. In the Iranian context, traditional collectivist values, alongside gender-specific social expectations, create a unique framework for understanding relational intrusions (12, 13). For example, behaviors that may be considered intrusive or inappropriate in Western individualistic cultures may be interpreted as expressions of genuine romantic interest or commitment in Iran (14). This cultural framing is especially evident in attitudes toward persistent courtship, which is often idealized in Iranian narratives as a sign of devotion and sincerity rather than intrusion (15).

Moreover, the increasing digitalization of Iranian society — with internet usage exceeding 84% by 2022 (16) — has introduced new dimensions to ORI. Digital platforms enable persistent contact, anonymity, and surveillance, complicating both the manifestation and the recognition of intrusive relational behaviors (17). These developments, when combined with traditional values around romance and relationship pursuit, create culturally specific expressions of ORI that may not be adequately captured by existing Western-developed instruments.

Despite growing awareness of ORI, there remains a notable lack of empirical research within Middle Eastern populations. This research gap is critical, as cultural context significantly shapes both the expression and psychological consequences of ORI (1). The absence of validated, culturally sensitive assessment tools presents a substantial barrier to both clinical evaluation and scholarly investigation (18).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to address this gap by validating the Persian version of the ORI-VSF among Iranian adults. By examining its factor structure, psychometric properties, and gender-based measurement invariance, the study seeks to provide a reliable and culturally appropriate tool for assessing ORI in Persian-speaking populations. The findings are expected to contribute to a broader cross-cultural understanding of intrusive relational behaviors and support the development of context-sensitive interventions and assessments.

3. Methods

3.1. Translation Procedure

The translation procedure adhered to the guidelines outlined by Beaton et al. (18) for the cross-cultural adaptation of self-report instruments. This process included forward translation, synthesis, back-translation, expert committee review, and pretesting. Two independent bilingual translators participated in the forward translation from English to Persian — one familiar with the subject matter (a clinical psychologist) and the other unfamiliar with the concepts (a linguist). Discrepancies between translations were resolved through discussion, resulting in a synthesized version. This synthesized version was then back-translated into English by two different translators who were blinded to the original version. An expert committee — consisting of the translators, a methodologist, and two language professionals — reviewed all versions to ensure semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence. The pre-final Persian version of the ORI-VSF was piloted with 30 individuals to assess clarity, comprehensibility, and cultural relevance. Based on participant feedback, minor adjustments were made, and the final version was established.

3.2. Procedure

This study employed a cross-sectional design. The target population comprised individuals aged 18 - 50 years residing in Zanjan, Iran. Data collection took place between January 2024 and August 2024 using convenience sampling. Participants were recruited through a multi-platform online strategy. Study announcements — including a brief description and survey link — were distributed through popular social media platforms and university student forums in Zanjan. Interested individuals who accessed the link were first presented with an information sheet outlining the study’s objectives, procedures, confidentiality assurances, the voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Informed consent was obtained digitally by requiring participants to actively click an “I agree to participate” button before accessing the survey.

Inclusion criteria for participation were: (1) Iranian citizenship and residence in Zanjan, (2) age between 18 and 50 years, (3) fluency in Persian, and (4) provision of informed consent. Participants were excluded if they displayed inconsistent or random response patterns, identified via embedded validity check items. Out of 791 initial responses, 18 were excluded based on these criteria, resulting in a final sample of 773 valid participants. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZUMS.REC.1403.046).

3.3. Participants

The final sample included 773 individuals, of whom 245 (31.6%) were male and 528 (68.3%) were female. The participants’ mean age was 26.45 ± 8.06 years, with ages ranging from 18 to 60 years. All participants were Iranian citizens and fluent Persian speakers.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Obsessive Relational Intrusion-Victim Short Form

The ORI-VSF is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 23 items developed by Spitzberg and Cupach (19). This measure serves to assess the extent and characteristics of pursuit behaviors experienced by an individual targeted by such behavior. The ORI-VSF yields three distinct scores: A total score, a pursuit dimension score, and an aggression dimension score. The overall degree of ORI experienced is calculated by summing an individual’s scores on all items, resulting in a total score for each individual (8). The ORI-VSF demonstrates high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha, a measure of internal consistency, consistently exceeding 0.86 for both the pursuit and aggression dimensions (20).

3.4.2. Relational Rumination Questionnaire

The Relational Rumination Questionnaire (RelRQ) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 16 items developed by Senkans et al. (21). Rumination on romantic relationships has been consistently associated with interpersonal difficulties, including intimate partner violence and stalking of former partners. Factor analysis studies identified a three-factor structure, which was subsequently refined into a 16-item version. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (never, rarely, somewhat, often, always). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the RelRQ were above 0.90, indicating excellent internal consistency (21). The Persian version has shown strong construct validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) in Iranian samples (12).

3.4.3. Obsessional Relational Intrusion and Celebrity Stalking Scale

The Obsessive Relational Intrusion and Celebrity Stalking Scale (ORI&CS) is an 11-item scale rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Factor analysis identified two distinct factors: Persistent pursuit and threat. The internal consistency reliability, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.80 for persistent pursuit and 0.77 for threat (22). The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the ORI&CS was 0.79, indicating acceptable internal consistency (23). In the present study, the Persian version of the ORI&CS demonstrated strong reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.858.

3.4.4. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21) is a brief version of the original DASS self-report scale. It comprises 21 items assessing the presence and severity of symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, and stress experienced over the past week, developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (24). Participants rate their responses on a 4-point Likert scale (0 - 3). The scale consists of three subscales, each with seven items. Subscale scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. The Persian version has shown strong construct validity and reliability with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.93, 0.79, and 0.91 for depression, anxiety, and stress subscales, respectively (25).

3.4.5. Satisfaction with Life Scale

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a self-report instrument with five items designed to assess the cognitive aspect of subjective well-being (26). Participants rate their agreement with statements using a 7-point Likert scale. Scores range from 5 to 35, with higher values indicating greater levels of life satisfaction (26). The Persian SWLS has shown strong construct validity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) in Iranian samples, and the scale has demonstrated good discriminant validity with measures of psychological distress in Iranian samples (27).

3.5. Data Analysis Method

The first step in the analysis was to conduct a descriptive analysis of the data to understand the distribution of demographic variables, ORIs, and relational rumination among participants. We employed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) rather than exploratory factor analysis (EFA) as our primary analytical strategy since the ORI-VSF has a well-established two-factor structure (pursuit and aggression) previously validated by Spitzberg and Cupach (6, 19). This approach is consistent with best practices in cross-cultural validation studies where the goal is to confirm whether an established factor structure holds in a new cultural context (18).

The CFA was conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) method to evaluate the two-factor model. Model fit was assessed using the following indices: Chi-square fit statistics (CMIN/DF), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, 90% CI). Goodness of fit was defined as CMIN/DF ≤ 3, TLI, GFI, and CFI ≥ 0.900, and RMSEA ≤ 0.05 (28).

Measurement invariance was employed to assess the degree of invariance between genders. This analysis evaluates whether the construct of intrusive thought appraisals is measured in the same way for both genders, ensuring the reliability and validity of comparisons across groups. Measurement invariance was tested using a series of increasingly constrained models, including configural, metric, and scalar. Model fit was compared using the change in CFI (ΔCFI) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) between the less restrictive and more restrictive models. Cutoff values for acceptable invariance were ΔRMSEA ≤ 0.015 and ΔCFI ≤ 0.01 (29).

To assess the questionnaire’s internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated. Additionally, convergent and discriminant validity was assessed by examining its correlations with the other relational measures. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 27 for descriptive statistics, and AMOS version 24 for CFA.

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

The relationship status of the participants, categorized by gender into four groups (married, in a romantic relationship, with a history of romantic relationships in the past, and without experience of a romantic relationship), is shown in Table 1. In both groups, the majority of participants either had a history of romantic relationships or were currently in a relationship. In terms of educational status, 23.8% of men and 20.7% of women were postgraduate students. The mean score for obsessional relational intrusions and relational rumination is also presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Men (N = 245) | Women (N = 528) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 26.19 ± 7.29 | 26.57 ± 8.40 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 29 (11.9) | 148 (28.0) |

| In relationship | 35 (14.3) | 111 (21.0) |

| Previously partnered | 88 (35.7) | 141 (26.7) |

| Never partnered | 93 (38.1) | 128 (24.2) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Undergraduate | 190 (76.2) | 421 (79.3) |

| Postgraduate | 55 (23.8) | 107 (20.7) |

| ORI-VSF | 10.93 ± 13.34 | 10.73 ± 12.88 |

| RelRQ | 33.97 ± 13.88 | 33.32 ± 13.87 |

| ORI&CS | 26.86 ± 10.36 | 23.70 ± 9.65 |

Abbreviations: ORI-VSF, Obsessive Relational Intrusion-Victim Short Form; RelRQ, Relational Rumination Questionnaire; ORI&CS, Obsessional Relational Intrusion and Celebrity Stalking Scale.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

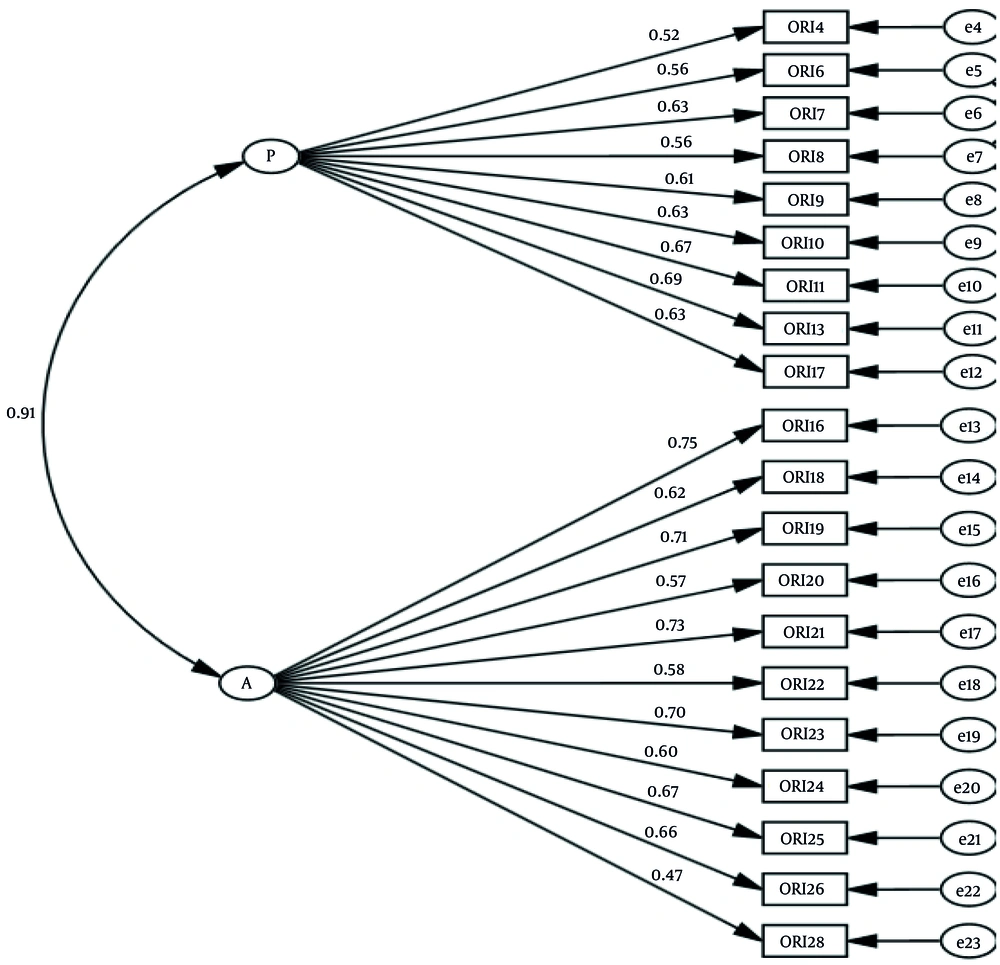

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The CFA was conducted using Amos version 24 to assess and validate the factor structures proposed by Spitzberg et al. (8). The results showed that items 1, 2, and 3 had factor loadings below 0.4 and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Subsequently, the two-factor model proposed by Spitzberg et al. was confirmed and showed excellent fit indices (8). Table 2 displays the factor loadings of the items, which ranged from 0.466 in item 7 to 0.754 in item 10. The results of the CFA are presented in Figure 1, and the model fit indices are reported in Table 3.

| Items | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Factor 1: Pursuit | ||

| 1. Following you around (e.g., following you to or from work, school, home, gym, daily activities, etc.) | 0.520 | - |

| 2. Intruding uninvited into your interactions (e.g., "hovers" around your conversations, offers unsolicited advice, initiates conversations when you are clearly busy, etc.) | 0.564 | - |

| 3. Invading your personal space (e.g., getting too close to you in conversation, touching you, etc.) | 0.632 | - |

| 4. Involving you in activities in unwanted ways (e.g., enrolling you in programs, putting you on mailing lists, using your name as a reference, etc.) | 0.557 | - |

| 5. Invading your personal property (e.g., handling your possessions, breaking and entering into your home, showing up at your door or car, etc.) | 0.610 | - |

| 6. Intruding upon your friends, family or coworkers (e.g., trying to befriend your friends, family or coworkers; seeking to be invited to social events, seeking employment at your work, etc.) | 0.633 | - |

| 7. Monitoring yourself and/or your behavior (e.g., calling at all hours to check on your whereabouts, checking up on you through mutual friends, etc.) | 0.671 | - |

| 8. Covertly obtaining private information (e.g., listening to your message machine, taking photos of you without your knowledge, stealing your mail or E-mail, etc.) | 0.686 | - |

| 9. Engaging in regulatory harassment (e.g., filing official complaints, spreading false rumors to officials — boss, instructor, etc., obtaining a restraining order on you, etc.) | 0.632 | - |

| Factor 2: Aggression | ||

| 10. Physically restraining you (e.g., grabbing your arm, blocking your progress, holding your car door while you’re in the car, etc.) | - | 0.754 |

| 11. Stealing or damaging valued possessions (e.g., you found property vandalized; things missing or damaged that only this person had access to, such as prior gifts, pets, etc.) | - | 0.622 |

| 12. Threatening to hurt him-or herself (e.g., vague threats that something bad will happen to him- or herself, threatening to commit suicide, etc.) | - | 0.705 |

| 13. Threatening others you care about (e.g., threatening harm to or making vague warnings about romantic partners, friends, family, pets, etc.) | 0.566 | |

| 14. Verbally threatening you personally (e.g., threats or vague warnings that something bad will happen to you, threatening personally to hurt you, etc.) | - | 0.726 |

| 15. Leaving or sending you threatening objects (e.g., marked up photographs, photographs taken of you without your knowledge, pornography, weapons, etc.) | - | 0.580 |

| 16. Showing up at places in threatening ways (e.g., showing up at class, office or work, from behind a corner, staring from across a street, being inside your home, etc.) | - | 0.699 |

| 17. Sexually coercing you (e.g., forcefully attempted/succeeded in kissing, disrobing, or feeling you, exposed him/herself, forced sexual behavior, etc.) | - | 0.601 |

| 18. Physically threatening you (e.g., throwing something at you, acting as if s/he will hit you, running finger across neck implying throat slitting, etc.) | - | 0.668 |

| 19. Physically hurting you (e.g., pushing or shoving you, slapping you, hitting you with fist, hitting you with an object, etc.) | - | 0.656 |

| 20. Physically endangering your life (e.g., trying to run you off the road, displaying a weapon in front of you, using a weapon to subdue you, etc.) | - | 0.466 |

| Model | χ2 (df) | P-Value | CFI | TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor structure invariance | |||||

| 2-Factor 20-item ORI-VSF a | 417.04 (142) | - | 0.960 | 0.946 | 0.050 |

| Measurement invariance | |||||

| Configural invariance | 755.19 (284) | < 0.001 b | 0.913 | 0.934 | 0.046 (0.042; 0.050) |

| Metric invariance | 817.62 (302) | < 0.001 b | 0.907 | 0.928 | 0.047 (0.043; 0.051) |

| Scalar invariance | 833.90 (305) | < 0.001 b | 0.904 | 0.926 | 0.047 (0.044; 0.051) |

Abbreviations: GFI, Goodness of Fit Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; ORI-VSF, Obsessive Relational Intrusion-Victim Short Form.

a GFI = 0.950.

b A P-value of < 0.001 is considered statistically significant.

4.3. Measurement Invariance

Table 3 presents the results of the measurement invariance testing for the two-factor model. The model displayed satisfactory fit indices for both males and females, as indicated by the TLI, CFI, and RMSEA. Additionally, the configural, metric, and scalar invariance models tested between gender groups showed satisfactory fit indices based on the TLI, CFI, and RMSEA. Only the configural invariance models exhibited minimal degradation in model fit (Δx2 = 62.43; P < 0.001; ΔCFI = -0.006; ΔTLI = -0.006; ΔRMSEA < 0.001), as well as between the metric and scalar invariance models (Δx2 = 16.28; P < 0.001; ΔCFI = -0.003; ΔTLI = -0.002; ΔRMSEA < 0.001). Consequently, in accordance with Chen’s (30) recommendations, invariance was established for the two-factor model across both genders.

4.4. Reliability Analysis

Multiple reliability indices were calculated to assess the internal consistency of the Persian ORI-VSF. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were excellent for the total scale (α = 0.919) and good to excellent for the subscales (pursuit: α = 0.845; aggression: α = 0.894). Additionally, McDonald’s omega coefficients, which provide a more robust measure of internal consistency based on the factor analytic approach, were calculated. The omega coefficients were similarly strong for the total scale (ω = 0.920) and both subscales (pursuit: ω = 0.860; aggression: ω = 0.910), confirming the high reliability of the Persian ORI-VSF. These results indicate that the Persian version of the ORI-VSF demonstrates strong internal consistency across different reliability estimation methods.

4.5. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

To evaluate the convergent and discriminant validity of the 20-item Persian ORI-VSF, correlations were estimated between the total score and subscales with theoretically related and unrelated constructs. As shown in Table 4, evidence for convergent validity was demonstrated through significant positive correlations between the ORI-VSF total score and relational rumination (R = 0.275, P < 0.01), as well as with the ORI&CS (R = 0.127, P < 0.01). Additionally, the ORI-VSF total score showed a significant positive correlation with psychological distress as measured by the DASS (R = 0.234, P < 0.01).

Abbreviation: ORI, obsessive relational intrusion; ORI-P, obsessive relational intrusion-pursuit; ORI-A, obsessive relational intrusion-aggression; RelRQ, Relational Rumination Questionnaire; ORI&CS, Obsessional Relational Intrusion and Celebrity Stalking Scale; DASS, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales; SWLS, Satisfaction with Life Scale.

a Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

b Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

Discriminant validity was supported by the significant but modest negative correlation between the ORI-VSF total score and life satisfaction as measured by the SWLS (R = -0.149, P < 0.01). This pattern of correlations aligns with theoretical expectations, where ORI victimization should be positively associated with psychological distress and rumination but negatively related to well-being measures. The magnitude of these correlations (weak to moderate) further supports the distinctiveness of the ORI-VSF construct from related but separate psychological phenomena.

5. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to validate the Persian version of the ORI-VSF among Iranian adults. The findings support the psychometric soundness of the instrument, demonstrating a stable two-factor structure, strong internal consistency, robust convergent and discriminant validity, and measurement invariance across genders. These results align with the original validation study by Spitzberg et al. (8), indicating that the ORI-VSF is a reliable and valid tool across cultural contexts.

The CFA supported the original two-factor model, though three items (1, 2, and 3) were removed due to low factor loadings (below 0.40). These items — related to unwanted messages and unsolicited gifts — may be interpreted differently in the Iranian cultural context, where such behaviors are sometimes normalized or even romanticized. This highlights the importance of cultural adaptation when applying psychometric instruments across different societies (18).

The establishment of measurement invariance across genders is a key strength, ensuring that the ORI-VSF assesses the same construct for both men and women. This is particularly significant in Iranian society, where gender roles and expectations may shape the way intrusive behaviors are experienced and reported. Prior studies emphasize the necessity of testing for measurement invariance to enable accurate gender-based comparisons and avoid interpretive biases (29, 30).

The Persian ORI-VSF also demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.919), slightly exceeding the reliability coefficients reported in the original version (α = 0.86 - 0.90). This indicates that the instrument measures ORI behaviors reliably with minimal error. Furthermore, the scale showed strong convergent and discriminant validity, as evidenced by its significant correlations with related constructs such as relational rumination, psychological distress, and life satisfaction (31-34). These findings reinforce the utility of the ORI-VSF in assessing the psychological burden of intrusive relational behaviors, which have been consistently associated with anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms (4, 35).

By enabling the reliable assessment of ORI in Iranian samples, the validated Persian ORI-VSF offers valuable implications for both research and clinical practice. Clinicians may use the tool to identify individuals at risk for ORI-related distress, and researchers can utilize it to study the prevalence and psychological impact of these behaviors in culturally specific ways (36, 37).

5.1. Conclusions

The validation of the Persian version of the ORI-VSF marks a significant improvement in assessing ORI behaviors within the Iranian cultural context. The findings of this study confirmed the two-factor structure through CFA (χ2 = 417.04, CFI = 0.960, RMSEA = 0.050) and demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.919), along with robust convergent and discriminant validity. Moreover, the ORI-VSF exhibited full measurement invariance across genders, enabling meaningful gender-based comparisons in future studies. These psychometric strengths establish the Persian ORI-VSF as a reliable and culturally appropriate instrument for both research and clinical applications in Iran. In conclusion, this study expands the cross-cultural applicability of ORI assessment tools and provides a strong foundation for further research on stalking and intrusive relational behaviors in non-Western societies.

5.2. Strengths and Contributions

This study presents several notable contributions. First, it is the first to validate the ORI-VSF in a non-Western context, addressing a significant gap in the availability of culturally appropriate tools for assessing ORI. Until now, the instrument had only been validated in its original English version, and this study expands its cross-cultural applicability. Second, the validation process employed a comprehensive psychometric evaluation, including assessments of factorial structure, reliability (Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega), and both convergent and discriminant validity. Third, the confirmation of measurement invariance across genders adds methodological rigor and supports the instrument’s use in comparative gender analyses within Iranian populations. Collectively, these strengths underscore the value of the Persian ORI-VSF as a psychometrically sound tool for both research and clinical use in Iran.

5.3. Limitations

Despite these strengths, several limitations must be acknowledged. The use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader Iranian population. Future studies should consider probability sampling methods to increase representativeness. Additionally, since participants were recruited from a single province (Zanjan), the findings may not reflect the cultural diversity present across different regions of Iran.

The cross-sectional nature of the study also limits inferences about causality. Longitudinal research is needed to examine the temporal relationships and potential causal pathways between ORI behaviors and psychological outcomes (2).

5.4. Future Directions

Moreover, while the Persian ORI-VSF has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, further validation in diverse subgroups within Iran — such as different age ranges and educational backgrounds — would enhance the assessment of its applicability. Future research is recommended to recruit participants from various provinces across Iran to better capture cultural diversity and improve the generalizability of findings. Qualitative approaches may also enrich understanding by exploring victims’ lived experiences and the nuanced cultural meanings attached to ORI behaviors. Cross-cultural comparative studies would be especially beneficial for exploring how cultural norms and values influence the perception, expression, and psychological consequences of ORI across societies.