1. Background

Long COVID is emerging as a significant public health concern, with cognitive impairment affecting a substantial proportion of survivors. Studies estimate that 20% to 30% of individuals recovering from COVID-19 experience persistent cognitive symptoms, including memory deficits, attention difficulties, and executive dysfunction (1, 2). The burden of neurocognitive disorders in COVID-19 patients extends beyond the acute phase, with many individuals reporting symptoms for months. This pattern is consistent with previous viral epidemics, where cognitive complications have had long-lasting impacts on quality of life (3, 4).

The underlying mechanisms of COVID-19-related cognitive deficits remain under investigation, though several factors have been implicated. Hypoxia, neuroinflammation, and vascular dysfunction are among the leading contributors. Reduced blood oxygen levels during the acute phase of the illness have been linked to lower cognitive scores months after recovery (5, 6). Additionally, the inflammatory response associated with COVID-19 appears to play a key role. It has been associated with neuroinflammation, microglial activation, and neuronal damage, contributing to long-term cognitive decline (7, 8). Neuroinflammatory markers have also been observed at increased levels in patients with cognitive symptoms, correlating with poorer outcomes (9).

The impact of cognitive deficits in post-COVID-19 patients extends beyond health concerns, affecting daily activities, employment, and overall well-being. A meta-analysis of COVID-19 survivors highlights an increased risk of impaired work productivity and diminished quality of life among those experiencing cognitive dysfunction (10, 11).

2. Objectives

Given these significant consequences, systematic follow-up assessments of cognitive impairment in COVID-19 patients and a comprehensive evaluation of associated risk factors are essential. This study evaluates post-COVID-19 cognitive function at three months and one year using the blind montreal cognitive assessment (blind MoCA) and explores its association with demographic and clinical factors.

3. Methods

In this longitudinal study, we analyzed 260 symptomatic patients enrolled using a convenience sampling method, aged 18 to 75, who tested positive for COVID-19 via PCR and were admitted to Taleghani Hospital. We excluded individuals with cognitive disorders, those who declined participation, patients who died before the one-year follow-up, and non-Persian speakers. Data were collected through medical histories and interviews, focusing on two categories of risk factors:

1. Patient-related: Age, gender, education, underlying diseases, and psychiatric history

2. Disease-related: Pulmonary involvement, COVID-19 treatment drugs, oxygen level reductions, and key laboratory findings, including CBC, hemoglobin, LDH, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), D-dimer, sodium, potassium, calcium, and creatinine. Pulmonary involvement was classified based on thoracic CT scans, and the lowest oxygen saturation without an oxygen mask was recorded. Treatments included antibiotics, NSAIDs, antiviral drugs, anti-inflammatory medications, and corticosteroids.

Cognitive impairment was assessed with the blind MoCA questionnaire at three months and one year after discharge, suitable for telephone assessments during the lockdown. The MoCA test was administered by a psychiatry resident under the supervision of an attending physician trained in administering the test. Scores for the MoCA range from 0 to 22, with allocations of 6 points for attention, 3 for language, 2 for abstraction, 5 for delayed recall, and 6 for orientation. An extra point is given for patients with 12 years of education or less. A score of 19 or above is typically considered normal. The MoCA’s validity and reliability have been previously studied in Iran (12, 13). We used complete case analysis, excluding participants with missing cognitive or laboratory data. No imputation was performed.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Quantitative variables were expressed as means with standard deviations (Mean ± SD), and qualitative variables as frequencies and percentages. Between-group comparisons at each follow-up were performed using independent-samples t-tests for normally distributed variables, Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed binary variables, one-way ANOVA for continuous variables with more than two groups, and Kruskal-Wallis tests for ordinal variables. Within-group changes between the three-month and one-year follow-up were assessed using paired-samples t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, as appropriate. Correlations between quantitative variables were evaluated using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients based on distributional assumptions. To account for baseline differences and control for potential confounders, variables with a P-value < 0.25 in univariate analyses were included in a multiple analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model, with baseline blind MoCA scores entered as covariates. Model outputs included regression coefficients, 95% confidence intervals, significance levels, and partial eta-squared values. All graphical illustrations were created using GraphPad Prism version 8, and a two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

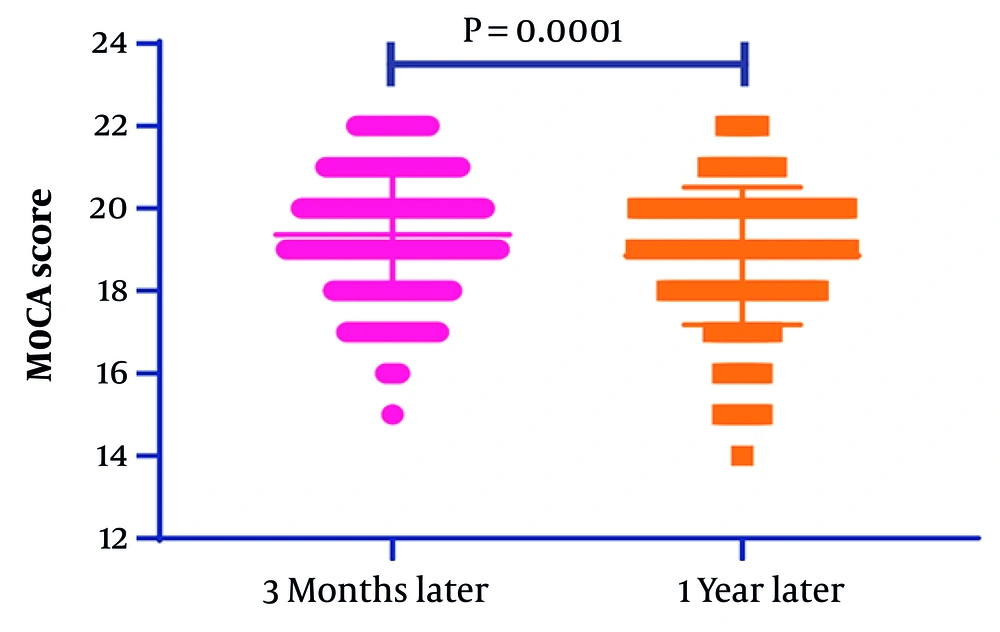

The study examined 260 patients and found that their average cognitive scores dropped from 19.36 ± 1.53 three months post-discharge to 18.85 ± 1.66 one year later, with a statistically significant P-value of 0.0001 (Figure 1). The number of individuals with cognitive impairment also increased from 72 (27.69%) to 94 (36.15%) over the same period, based on a cutoff score of 19 for normal cognitive status. Table 1 summarizes the qualitative variables and compares patient characteristics with mean blind MoCA scores at the three-month and one-year follow-up assessments. Variables including gender, education level, comorbidities, and medical history were examined for their association with recovery scores. Significant differences in mean scores were observed according to education level, presence of comorbidities, history of psychiatric disorders, psychiatric drug use, severity of pulmonary involvement, and type of medication received. Patients with lower educational attainment, comorbid conditions, hypertension, and severe pulmonary involvement tended to have lower blind MoCA scores at both time points. Moreover, individuals who received psychiatric counseling had significantly lower mean scores at both follow-up assessments.

| Variables and Categories | No. (%) | Three-Month Follow-up (Mean ± SD) | P-Value a | One-Year Follow-up (Mean ± SD) | P-Value a | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.08 | 0.1 | ||||

| Male | 148 (56.9) | 19.23 ± 1.62 | 18.71 ± 1.85 | < 0.001 | ||

| Female | 112 (43.1) | 19.55 ± 1.41 | 19.04 ± 1.37 | < 0.001 | ||

| Education | < 0.001 | 0.02 | ||||

| Cycle | 42 (16.2) | 18.40 ± 1.27 | 18.12 ± 1.11 | 0.05 | ||

| Diploma | 86 (33.1) | 19.47 ± 1.58 | 19.05 ± 1.78 | < 0.001 | ||

| Associate degree | 13 (5.0) | 20.08 ± 1.66 | 19.31 ± 1.65 | 0.001 | ||

| BSc | 71 (27.3) | 19.52 ± 1.63 | 18.82 ± 2.02 | < 0.001 | ||

| MSc | 33 (12.7) | 19.73 ± 1.01 | 19.30 ± 0.88 | 0.001 | ||

| PhD | 15 (5.8) | 19.40 ± 1.45 | 18.53 ± 1.19 | 0.004 | ||

| Comorbidities | 0.001 | 0.09 | ||||

| No | 161 (61.9) | 19.61 ± 1.56 | 18.98 ± 1.75 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 99 (38.1) | 18.97 ± 1.41 | 18.64 ± 1.51 | < 0.001 | ||

| DM | 0.35 | 0.25 | ||||

| No | 233 (89.6) | 19.40 ± 1.51 | 18.81 ± 1.68 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 27 (10.4) | 19.07 ± 1.73 | 19.19 ± 1.59 | 0.542 | ||

| Hypertension | < 0.001 | 0.008 | ||||

| No | 215 (82.7) | 19.52 ± 1.54 | 18.97 ± 1.67 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 45 (17.3) | 18.64 ± 1.28 | 18.27 ± 1.54 | 0.001 | ||

| Thyroid disease | 0.4 | 0.72 | ||||

| No | 244 (93.8) | 19.35 ± 1.54 | 18.84 ± 1.67 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 16 (6.2) | 19.69 ± 1.54 | 19.00 ± 1.71 | < 0.001 | ||

| Heart disease | 0.25 | 0.5 | ||||

| No | 240 (92.3) | 19.40 ± 1.54 | 18.87 ± 1.67 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 20 (7.7) | 19.00 ± 1.45 | 18.60 ± 1.70 | 0.028 | ||

| Psychiatry history | 0.002 | 0.09 | ||||

| No | 254 (97.7) | 19.40 ± 1.54 | 18.88 ± 1.66 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 6 (2.3) | 18.00 ± 0.63 | 17.50 ± 1.64 | 0.415 | ||

| Psychiatric drug history | < 0.001 | 0.04 | ||||

| No | 169 (65.0) | 19.62 ± 1.51 | 18.99 ± 1.67 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 91 (35.0) | 18.91 ± 1.48 | 18.58 ± 1.64 | < 0.001 | ||

| D-dimer | 0.94 | 0.02 | ||||

| Negative | 189 (92.2) | 19.42 ± 1.56 | 18.94 ± 1.64 | < 0.001 | ||

| Positive | 15 (7.3) | 19.53 ± 1.13 | 19.40 ± 0.91 | 0.61 | ||

| Pulmonary involvement | 0.002 | 0.001 | ||||

| Mild | 63 (24.2) | 19.86 ± 1.32 | 19.40 ± 1.44 | < 0.001 | ||

| Moderate | 120 (46.2) | 19.39 ± 1.58 | 18.87 ± 1.78 | < 0.001 | ||

| Severe | 77 (29.6) | 18.94 ± 1.52 | 18.36 ± 1.53 | < 0.001 | ||

| Received medications | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Remdesivir+dexamethasone+famotidine | 209 (80.4) | 19.61 ± 1.42 | 19.13 ± 1.50 | < 0.001 | ||

| Remdesivir+dexamethasone+tavanex | 50 (19.2) | 18.36 ± 1.60 | 17.64 ± 1.80 | < 0.001 | ||

| Psychiatry counseling | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| No | 247 (95.0) | 19.48 ± 1.49 | 18.96 ± 1.63 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 13 (5.0) | 17.31 ± 0.85 | 16.77 ± 0.93 | 0.047 |

Abbreviation: DM, type 2 diabetes.

a The P-values for group differences in blind MoCA scores for categorical variables were calculated using the Mann-Whitney U test for binary non-parametric variables, independent-samples t-test for binary parametric variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test for ordinal categorical variables, and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables with more than two groups.

b The P-values represent within-group changes in blind MoCA scores between the three-month and one-year follow-up, calculated using paired-samples t-tests for normally distributed differences or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for non-normally distributed differences.

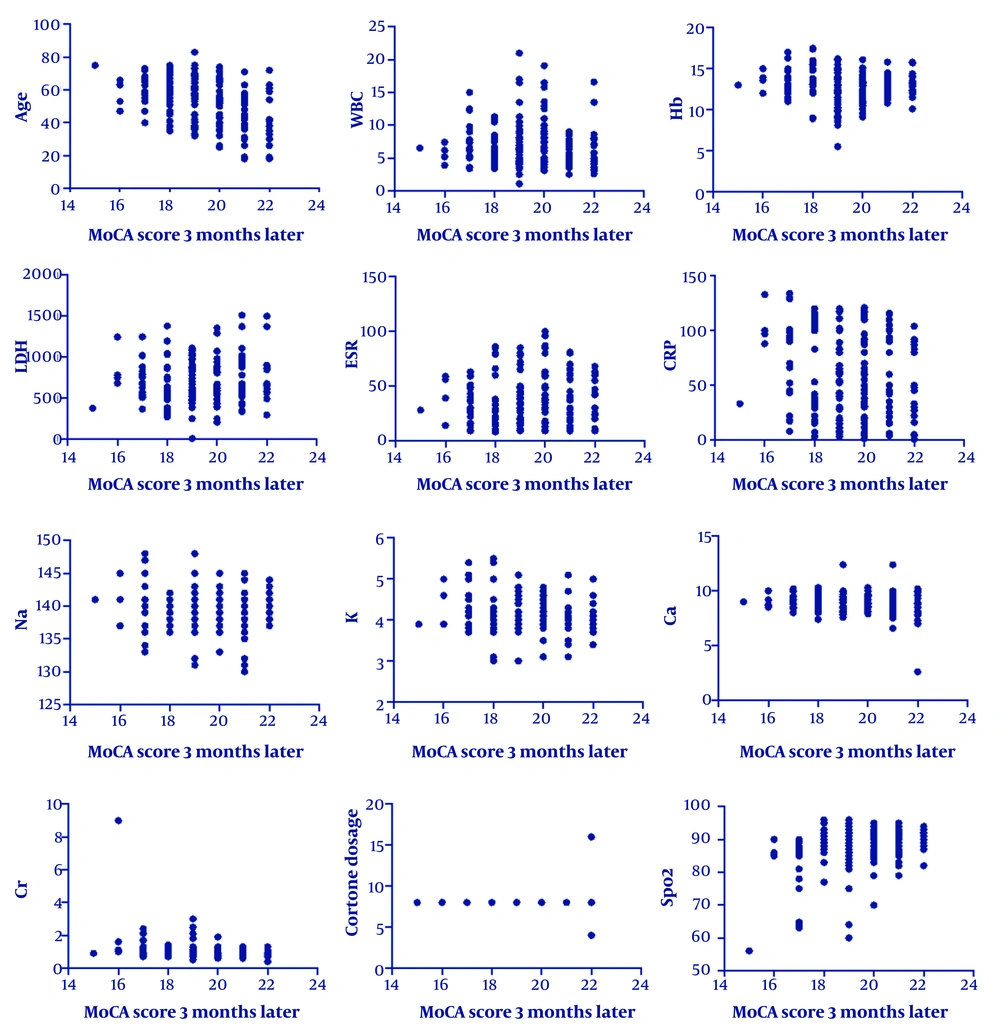

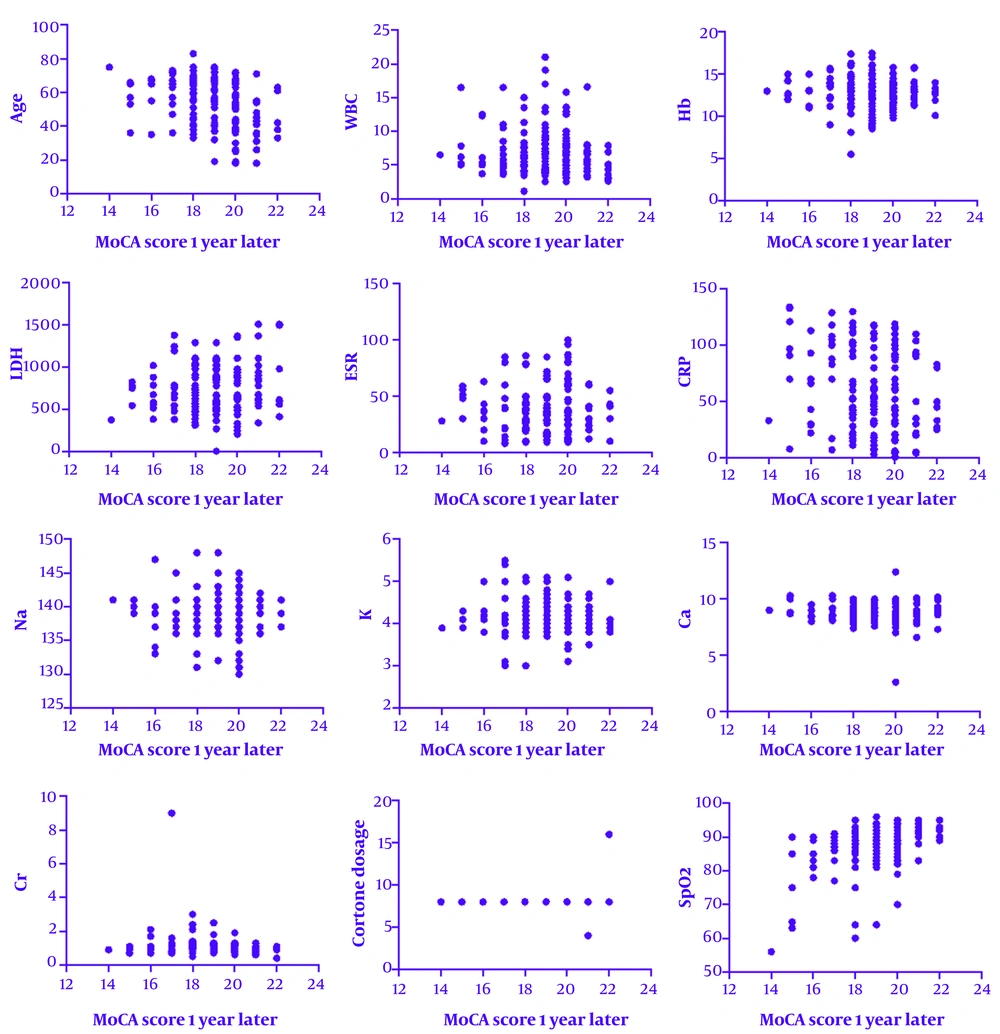

As shown in Table 2, age, CRP, creatinine, and oxygen saturation showed statistically significant correlations with MoCA scores. These effect sizes represent moderate associations, particularly for age and oxygen levels, suggesting a meaningful impact on long-term cognitive outcomes.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Three Months After Discharge; r (P-Value) | One Year After Discharge; r (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.94 ± 13.80 | -0.41 (0.0001) | -0.3 (0.0001) |

| WBC | 6.86 ± 3.32 | -0.03 (0.59) | -0.06 (0.3) |

| Hb | 12.90 ± 1.78 | -0.08 (0.17) | -0.07 (0.24) |

| LDH | 724.20 ± 296.84 | 0.07 (0.21) | 0.06 (0.27) |

| ESR | 39.41 ± 22.74 | 0.04 (0.52) | 0.06 (0.27) |

| CRP | 59.07 ± 37.19 | -0.16 (0.006) | -0.21 (0.001) |

| Na | 139.52 ± 2.93 | 0.001 (0.98) | -0.03 (0.6) |

| K | 4.13 ± 0.40 | -0.09 (0.14) | -0.06 (0.28) |

| Ca | 8.85 ± 0.90 | -0.07 (0.22) | -0.08 (0.16) |

| Cr | 0.97 ± 0.58 | -0.23 (0.0001) | -0.15 (0.01) |

| O2 | 87.24 ± 6.51 | -0.41 (0.0001) | -0.3 (0.0001) |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP, C-reactive protein; Ca, calcium; Cr, creatinine.

Figures 2 and 3 show that the scores obtained by the patients had a significant inverse correlation with age, CRP level, and creatinine level. This means that an increase in these parameters was correlated with decreased MoCA scores.

After adjusting for baseline blind MoCA scores and potential confounders, multiple ANCOVA analysis identified several significant predictors of one-year cognitive performance (Table 3). Higher baseline scores were strongly associated with higher follow-up scores (B = 0.882, 95% CI, 0.799 - 0.964; P < 0.001). Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) was linked to lower cognitive outcomes (B = 0.826, 95% CI, 0.417 - 1.234; P < 0.001), while receiving specific medication regimens was associated with reduced scores (B = -0.351, 95% CI, -0.631 to -0.070; P = 0.015). Higher CRP levels (P = 0.001) and ESR (P = 0.012) were also significantly related to poorer cognitive performance. No significant associations were observed for age, comorbidities, white blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin, calcium, or creatinine levels.

| Variables | B | 95% CI (Lower to Upper) | P-Value | Partial Eta2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline score | 0.882 | 0.799 to 0.964 | < 0.001 | 0.643 |

| Age | 0.001 | -0.009 to 0.011 | 0.848 | 0 |

| Comorbidities | 0.166 | -0.133 to 0.465 | 0.274 | 0.005 |

| DM | 0.826 | 0.417 to 1.234 | < 0.001 | 0.06 |

| Received medications | -0.351 | -0.631 to -0.070 | 0.015 | 0.024 |

| WBC | -0.024 | -0.059 to 0.010 | 0.167 | 0.008 |

| Hb | 0.009 | -0.056 to 0.073 | 0.789 | 0 |

| CRP | -0.006 | -0.010 to -0.003 | 0.001 | 0.048 |

| ESR | 0.008 | 0.002 to 0.014 | 0.012 | 0.025 |

| Ca | -0.046 | -0.171 to 0.079 | 0.468 | 0.002 |

| Cr | 0.196 | -0.001 to 0.393 | 0.051 | 0.015 |

Abbreviations: DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Ca, calcium; Cr, creatinine.

5. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2, like other types of viral pneumonia such as SARS and MERS, can lead to cognitive impairment. This impairment may result from direct viral infection of the central nervous system, inflammatory responses from cytokine release, tissue hypoxia, and microangiopathy (14, 15). Although most individuals recover cognitive functions over time, the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions may experience long-term deficits (16). This study highlights the complexity of recovery outcomes related to cognitive impairment, underscoring the importance of demographic, clinical, and laboratory factors. The ANCOVA model showed that baseline Blind MoCA scores were the strongest predictor of one-year outcomes, indicating persistence of early deficits. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, higher CRP, and higher ESR were independently associated with poorer cognitive performance, highlighting the role of metabolic and inflammatory pathways. Receipt of specific medication regimens was also linked to lower scores, likely reflecting treatment intensity in more severe cases.

A survey of 969 individuals with SARS-CoV-2 found that 26% experienced mild cognitive impairment, suggesting that COVID-19 may affect cognitive functions (17). A meta-analysis of 2,049 subjects found that COVID-19 patients had lower MoCA scores than controls, with some cognitive decline persisting for up to seven months post-infection. An Italian follow-up study of 50 recovered patients revealed that about a quarter showed mild cognitive impairment 60 days post-discharge (18). A survey of 292 COVID-19 survivors indicated that those with greater physical impairment also experienced more cognitive decline (19). Similarly, a one-year prospective cohort study in China with 1,438 COVID-19 survivors and 438 uninfected adults aged 60 and older found that cognitive decline was significantly more pronounced in the infected group, particularly among those who had severe COVID-19 (20).

Our study found that higher CRP and ESR levels were associated with lower long-term cognitive scores, and decreased oxygen levels correlated with poorer cognitive performance. Increased levels of inflammatory factors in COVID-19 patients, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and CRP, can elevate microglial activity, promote neuroinflammation, and damage neurons and synaptic structures (7). Research shows a significant rise in neuroinflammatory markers in brain regions related to cognitive function, including the hippocampus, cerebellum, and anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroinflammation may significantly impact nerve damage and cognitive function during viral infections (9).

While some studies also indicated a connection between the severity of pulmonary involvement, elevated D-dimer levels, and cognitive disorders (21), no significant cognitive impairment has been reported in 35 COVID-19 patients immediately after discharge, but those who received oxygen therapy experienced greater deficits in attention, memory, and executive functions (6). These findings imply a link between hypoxia due to lung disease and the severity of cognitive impairment in certain COVID-19 patients, as hypoxia is known to potentially cause cognitive deficits (5). Internet-based tests involving over 84,000 individuals revealed significant cognitive impairments in memory, attention, and executive functions after COVID-19 recovery, correlated with age, gender, education level, and pre-existing conditions (10).

In a study assessing the link between demographics, social determinants of health, and cognitive outcomes six months after COVID-19 hospitalization using the T-MOCA test, it was found that lower education, black ethnicity, and unemployment were associated with abnormal T-MOCA scores, possibly due to undiagnosed cognitive issues, test biases, unmeasured social factors, or biological effects of SARS-CoV-2 (22). While it was anticipated that individuals with lower education would exhibit greater cognitive impairment, our results showed decreased scores even among those with postgraduate education, likely due to differences in education quality, which is challenging to quantify, and the impact of education on recovery post-SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unclear (21).

The present study has several limitations, including the lack of an age- and gender-matched control group of uninfected individuals. It did not assess other factors, like thyroid function and vitamin levels, that could impact cognitive ability. Additionally, the MoCA screening test may not effectively evaluate cognitive functions in highly educated individuals. The use of the Blind MoCA test for remote assessments during lockdowns may also lack the necessary sensitivity for this demographic. The generalizability of the findings is limited, as the study focused on patients from a single geographic region and did not include a control group. This prevents us from determining if the observed cognitive decline is unique to COVID-19 survivors. Another limitation of our study is the lack of subscale data from the Blind MoCA. As a result, we could not perform domain-specific analyses.

Future research should involve comprehensive evaluations of COVID-19 patients in larger, multi-center cohorts, considering both early and late effects, domain-specific analysis, and exploring additional factors influencing recovery. The findings have significant practical implications for managing post-COVID-19 cognitive impairments. Given the observed decline in cognitive function over time, early interventions such as cognitive rehabilitation programs, structured exercise regimens, and pharmacological treatments targeting neuroinflammation may be beneficial (23).

5.1. Conclusions

Our study identifies key factors that affect cognitive impairment during COVID-19 recovery after hospital discharge. Cognitive impairment often worsens over time. Routine cognitive screening, including biomarkers such as CRP, may help identify individuals at risk for long-term deficits. Targeted rehabilitation interventions — combining cognitive training and physical activity — should be developed and evaluated to support post-COVID recovery.