1. Background

Infertility is defined as the inability to conceive after 12 months of unprotected intercourse (1). Infertility stress refers to a constellation of symptoms that emerge following an infertility diagnosis and consists of five components: Social concern, sexual concern, relationship concern, need for parenthood, and rejection of a child-free lifestyle (2). Kim et al. reported that infertility stress affects not only the quality of life of the infertile individual but also that of their partner (3). Although this type of stress and the associated social concerns seem to have a stronger impact on women than on men, women experience more stress than men (4).

The relationship-focused model, developed by Coyne and Smith, emphasizes the ways in which partners can support one another in the face of stressors within the couple’s relationship (5). Stress can disrupt relationships; however, as Bodenmann highlighted, couples who engage in dyadic coping can mitigate these negative effects (6). Dyadic coping involves partners communicating their stress verbally or non-verbally and jointly managing the stressful situation (7). This process encompasses both individual and shared appraisal of the stressor, enabling partners to pool their resources toward a common goal. Notably, the sense of "we-ness" — experiencing stress as “ours” rather than “mine” or “yours” — acts as a key mechanism that buffers stress and strengthens relational resilience (8). In this way, partners support each other through both individual and joint efforts during stress caused by disease. When a couple engages in dyadic coping, both partners deal together with stressors that directly or indirectly affect them, plan together to address these factors, and express their emotions together, functioning as a team (9).

According to Gouin et al. (10), dyadic coping strategies can be categorized into positive dyadic coping, common dyadic coping, and negative dyadic coping. In positive dyadic coping, one partner helps the other by temporarily taking over responsibilities, or both partners cooperate to jointly address the stressor. Lee and Roberts demonstrated that relationship outcomes, such as closeness and mutual appreciation, can increase or decrease depending on the effectiveness of coping efforts. When coping is successful, stress is alleviated, leading to a harmonious relationship; conversely, ineffective coping results in persistent stress and ongoing incongruence in the relationship (4). Many couples experience relationship difficulties due to a lack of coping skills, with a significant portion of conflicts arising from this deficiency (11).

Resilience is a set of personal characteristics that facilitate adaptation to adverse conditions, improve stressful situations, and enable the use of positive coping strategies (12). Research has established that resilience patterns exist at both individual and family levels and can be explored through relational processes (13). Thus, resilience involves communication, addressing mutual empathy, trust, support, and awareness in times of crisis (14). Resilient couples are those who display sufficient flexibility and thrive even when confronted with stressors, discrimination, and adversity (15). It is therefore crucial for infertile couples to be resilient to overcome psychosocial distress and improve quality of life (16). Although relational resilience can alleviate pressure on couples during stressful times, it is a relatively new variable, and limited research has explored its relationship with stress.

Positive dyadic coping brings stability to individuals and couples, with its beneficial effects ultimately promoting health (17). In turn, relational resilience fosters couple growth, plays a vital role in reducing the impact of infertility stress, maintains positive relationships, and keeps partners attuned to each other (18, 19). In general, positive dyadic coping enriches relationships and strengthens couples' emotional bonds following acute stress, thereby building relational resilience. The greater the increase in positive dyadic coping, the higher the relational resilience (20), guiding families along an adaptive path to stress and collective success in overcoming challenges (21). According to Aydogan and Ozbay, dyadic coping positively affects the relational resilience of individual spouses (22), while Santa-Cruz et al. found that high levels of resilience are associated with reduced psychological stress (23).

2. Objectives

In Iran, most research on intrapersonal factors resulting from infertility has been limited, with marital relationship factors receiving little attention. Additionally, in Iran's collectivist culture, infertility can be especially stressful for women due to greater social pressure influenced by beliefs about childbearing. In contrast, in individualistic societies, infertility is viewed more as a personal loss and distress with profound emotional consequences. Moreover, since women experience more infertility stress than men (24) and positive dyadic coping affects resilience (20), the question arises as to which factors can precisely influence infertility stress in infertile women. Based on this, the hypothesis was formulated to determine whether relational resilience mediates the relationship between dyadic coping and infertility stress in infertile women.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

The statistical population comprised all women who attended the infertility center of Beheshti Hospital in Kashan and underwent various infertility treatments. Since a sample larger than 200 was required for structural equation modeling (SEM), and in coordination with a specialist in gynecology, childbirth, and infertility at the center, a purposive sample of 253 women was selected. After admission, the specialist doctor and a midwife introduced the participants to the researcher. During initial contact, patients received an explanation of the research, after which they were asked to complete the questionnaires within 20 minutes. Any ambiguities while completing the questionnaires were clarified by the researcher. If participants chose not to continue for reasons such as lack of time or concerns about confidentiality, they could voluntarily return the questionnaires. Ultimately, 35 questionnaires were discarded due to incomplete responses. Questionnaires with unanswered items were excluded from analysis, resulting in 218 usable questionnaires for analysis.

3.2. Participants

All participants were women receiving treatment at infertility centers. The inclusion criteria were: Being under infertility treatment, having been married for at least three years, and being at least 20 years old.

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Fertility Problems Inventory

The Fertility Problems Inventory (FPI) is a 46-item instrument designed to assess infertility stress (25). Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with 18 items reverse-scored. Total scores range from 46 to 276, with higher scores indicating greater infertility stress. The inventory comprises five scales: Social Anxiety, Sexual Anxiety, Relationship Anxiety, Need for Parenthood, and Rejection of a Child-Free Lifestyle. Zhang et al. reported Cronbach's alpha values of 0.90, 0.90, and 0.91 for infertility stress in the entire, male, and female samples, respectively (12). In the present study, the overall scale's reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.81.

3.3.2. Dyadic Coping Inventory

Developed by Bodenmann, this 37-item measure assesses dyadic coping behaviors (26). Each item uses a Likert scale from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often). The inventory evaluates several dimensions, including supportive, delegated, negative, and common dyadic coping, according to individual, spouse, and couple perceptions. It also assesses the relationship between stress and perceived dyadic coping quality. In this study, spousal positive coping and self-positive coping were examined. Positive dyadic coping includes the subscales of supportive dyadic coping, delegated dyadic coping, and common or joint dyadic coping (27). Chavez et al. found Cronbach's alpha values of 0.90 and 0.83 for men and women, respectively; spouse's positive dyadic coping was 0.81, and self-positive coping subscale was 0.84 (28). In this study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.85 for self-coping and 0.87 for spouse's coping.

3.3.3. Relational Resilience Questionnaire

This multidimensional self-report scale measures couples' ability to recover after traumatic life experiences. Developed by Aydogan and Ozbay, it includes 27 items on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from "never" to "always" (29). It features four subscales: Actor, Partner, Alliance, and Spirituality. Total scores range from 27 to 189, with higher scores indicating higher relational resilience. Chian and Aydogan reported Cronbach's alpha scores of 0.93 for actor, 0.90 for wife, 0.90 for unity, 0.95 for spirituality, and 0.96 for the overall scale; values for women and men were both 0.96 (14). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha was 0.94.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using AMOS 24 and SPSS 24. In the first stage, descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were calculated to summarize demographic characteristics and main study variables, providing an overview of the sample distribution and central tendencies. In the second stage, SEM in AMOS 24 examined hypothesized relationships according to the conceptual model and research objectives. Model fit was evaluated using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), with acceptable fit defined as CFI, GFI, and TLI values ≥ 0.90.

4. Results

Table 1 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in this research.

| Variables | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| 20 - 30 | 35.3 |

| 31 - 45 | 64.7 |

| Education | |

| High school diploma or lower | 56.9 |

| University degree | 43.1 |

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 70.6 |

| Employee | 29.4 |

| Having children | |

| No children | 69.3 |

| Have children | 21.7 |

| Psychological treatment | |

| No | 90.8 |

| Yes | 9.2 |

| Cause of infertility | |

| Known | 77.0 |

| Unknown | 33.0 |

| Duration of treatment (y) | |

| 1 - 5 | 80.0 |

| More than 5 | 20.0 |

| Type of infertility | |

| Primary | 48.0 |

| Secondary | 52.0 |

| Type of treatment | |

| Drug therapy | 49.5 |

| IVF | 23.4 |

| Stimulated ovulation | 11.0 |

| IUI | 21.0 |

| Economic status (million Tomans/mo) | |

| ≤ 10 | 89.0 |

| > 10 | 11.0 |

Based on Table 1, most participants were aged 31 - 45 years, and over half held a high school diploma or lower education. The majority were housewives and childless, and most had not received psychological treatment. In most cases, the cause of infertility was known, and the majority had undergone treatment for one to five years. The types of infertility were nearly evenly distributed between primary and secondary. Drug therapy was the most common treatment, followed by IVF and IUI. Most participants belonged to a lower economic status, earning less than 10 million Tomans per month. Table 2 presents means and standard deviations as the descriptive indices of and standardized (1 - 100) scores of the research variables.

| General Factors and Subscales | Scores in Terms of 100 | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Relational resilience | ||

| Partner | 76.6 | 33.37 ± 6.72 |

| Spirituality | 73.8 | 27.18 ± 5.02 |

| Union | 61.0 | 46.4 ± 9.29 |

| Actor | 80.0 | 35 ± 5.76 |

| Relational resilience | 70.8 | 141.96 ± 23.1 |

| Infertility stress | ||

| Social concern | 47.5 | 33.39 ± 8.4 |

| Sexual concern | 48.8 | 26.73 ± 7.27 |

| Relationship concern | 49.5 | 34.29 ± 7.4 |

| Need for parenthood | 66.0 | 44.27 ± 10.19 |

| Rejection of a child-free lifestyle | 81.0 | 39.9 ± 6.97 |

| Infertility stress | 58.7 | 178.61 ± 26.06 |

| Dyadic coping | ||

| Self-coping | 86.3 | 49.36 ± 5.88 |

| Partner coping | 79.9 | 47.43 ± 7.43 |

| Dyadic coping | 85.2 | 96.79 ± 11.35 |

According to Table 2, within the relational resilience subscales, 'Actor' (standardized score = 80.0) exhibited the highest level, while 'Union' (61.0) was the lowest. In the infertility stress subscales, 'Rejection of a child-free lifestyle' (81.0) was the highest, and 'Social Concern' (47.5) was the lowest. For dyadic coping, 'Self-Coping' (86.3) had the highest standardized score, with 'Partner Coping' (79.9) being slightly lower. Standardized scores facilitate direct comparison across subscales, with higher values reflecting higher levels of the respective construct. In the following, Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients of the research variables.

| Variables | Infertility Stress | Need for Parenthood | Relationship Concern | Sexual Concern | Social Concern | Dyadic Coping | Other Coping | Self-coping | Relational Resilience | Spirituality | Union | Partner | Actor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infertility stress | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Need for parenthood | 0.75 a | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Relationship concern | 0.70 a | 0.40 a | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sexual concern | 0.68 a | 0.29 a | 0.50 a | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social concern | 0.64 a | 0.24 a | 0.42 a | 0.39 a | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Dyadic coping | -0.29 a | -0.19 a | -0.21 a | -0.24 a | -0.14 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Partner coping | -0.33 a | -0.26 a | -0.23 a | -0.24 a | -0.17 b | 0.88 a | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Self-coping | -0.14 b | -0.05 | -0.10 | -0.17 a | -0.05 | 0.81 a | 0.44 a | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Relational resilience | -0.34 a | -0.14 b | -0.36 a | -0.37 a | -0.21 a | 0.52 a | 0.53 a | 0.33 a | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Spirituality | -0.11 | 0.02 | -0.21 a | -0.17 a | -0.09 | 0.23 a | 0.22 a | 0.16 b | 0.69 a | 1 | - | - | - |

| Union | -0.39 a | -0.23 a | -0.37 a | -0.39 a | -0.20 a | 0.48 a | 0.50 a | 0.30 a | 0.93 a | 0.51 a | 1 | - | - |

| Partner | -0.31 a | -0.15 b | -0.34 a | -0.33 a | -0.19 a | 0.53 a | 0.58 a | 0.29 a | 0.90 a | 0.51 a | 0.80 a | 1 | - |

| Actor | -0.25 a | -0.05 | -0.26 a | -0.31 a | -0.21 a | 0.49 a | 0.46 a | 0.36 a | 0.85 a | 0.48 a | 0.72 a | 0.69 a | 1 |

a P < 0.01.

b P < 0.05.

The results showed that infertility stress (social anxiety, sexual anxiety, and relationship anxiety) had a negative and significant relationship with dyadic coping and its subscales, except for the relationship of need for parenthood, relationship anxiety, and social anxiety with self-coping, which was not significant. The correlation between infertility stress and relational resilience was negative and significant. The relationship between conflict stress and relational resilience subscales (cohesion, partner, and actor) was also negative and significant, although its relationship with spirituality was not significant. All subscales of infertility stress had a negative and significant relationship with relational resilience. Relationship anxiety and sexual anxiety had a negative and significant relationship with all subscales of relational resilience. Social anxiety was negatively and significantly correlated with alliance, partner, and actor, but not with spirituality. The need for parenthood had a negative and significant relationship with alliance and partner, but not with spirituality or actor. Dyadic coping was positively and significantly correlated with relational resilience and all its subscales. All subscales of dyadic coping were positively and significantly associated with relational resilience and its subscales.

Before testing model fit, structural equation assumptions were assessed. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests for the dependent variable, infertility stress, indicated that the data distribution was normal. Model fitting showed a good fit to the data.

According to Table 4, the initial mediation model demonstrated an acceptable fit based on both Absolute and Comparative Fit indices (CFI, GFI, and TLI). However, the RFI was slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.90, suggesting that some modifications could improve the overall model fit.

| Modification | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | GFI | Pratio | RMSEA | X2/df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 2.54 |

| After | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 0.07 | 1.95 |

Abbreviations: TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; GFI, Goodness of Fit Index.

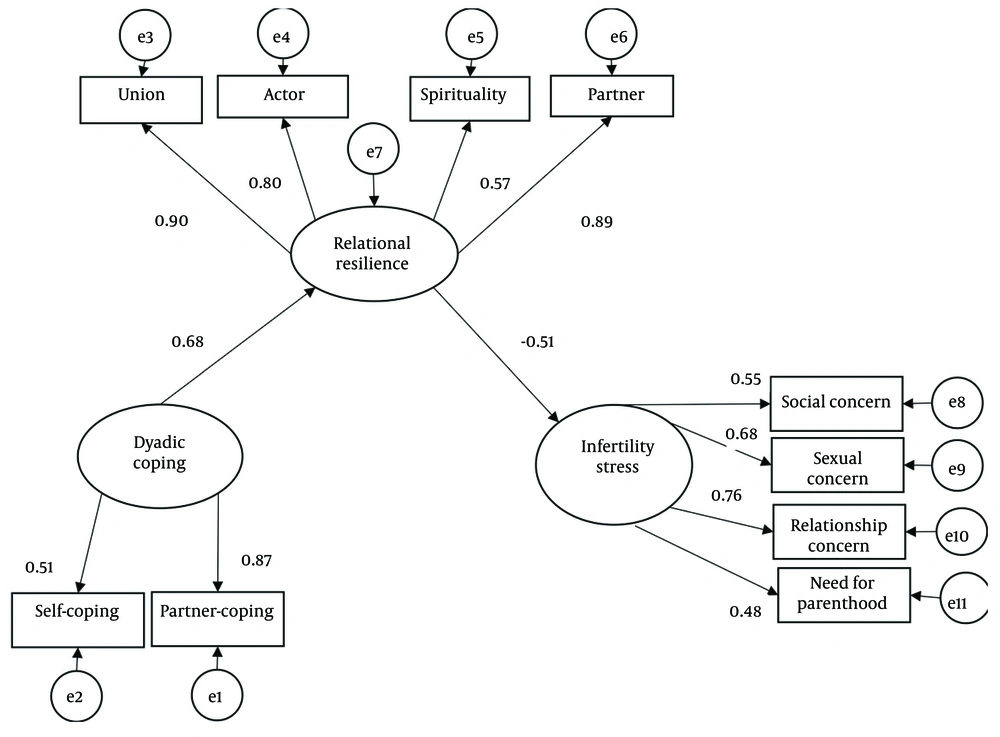

During model evaluation, it was found that the 'Rejection of a child-free lifestyle' subscale showed a weak correlation with the total infertility stress score. Given this poor correlation, the subscale was removed from the model for greater parsimony and theoretical consistency. The modified model was re-estimated to assess improvements in relationships among the remaining variables. In the revised model, the mediating role of relational resilience in the association between dyadic coping and infertility stress was tested among women undergoing infertility treatment (Figure 1). The modified model demonstrated favorable and improved fit indices compared to the initial model.

The final model represents a complete mediation model, with the non-significant direct path from dyadic coping to infertility stress removed. This modification yielded a higher overall fit, confirming that the effect of dyadic coping on infertility stress is fully mediated by relational resilience. In other words, dyadic coping indirectly influences infertility stress by enhancing relational resilience, which then reduces infertility-related stress.

Figure 1 illustrates the study variables and their respective subscales. Dyadic coping (including self-coping and partner coping) was positively and significantly associated with relationship resilience (union, partner, spirituality, and actor subscales). The correlation coefficient between these two variables was 0.68, indicating that higher dyadic coping is associated with greater relational resilience among women undergoing infertility treatment.

Conversely, the relationship between dyadic coping and infertility stress (including social concern, sexual concern, relationship concern, and need for parenthood) was negative but not significant (R = -0.08). Due to this lack of significance, the direct path was removed from the final model, resulting in a simpler and better-fitting structure. There was a negative and significant relationship between relationship resilience and infertility stress (R = -0.51). Table 5 shows the standardized and unstandardized regression weights of the model.

| Regression Weights | Standardize Estimate | P | Unstandardized Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dyadic coping → Relational resilience | 0.67 | 0.001 | 3.52 |

| Relational resilience → Infertility stress | -0.51 | 0.001 | -0.280 |

| Infertility stress → Social concern | 0.54 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Relational resilience → Union | 0.90 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Relational resilience → Actor | 0.79 | 0.001 | 0.54 |

| Relational resilience → Spirituality | 0.56 | 0.001 | 0.33 |

| Relational resilience → Partner | 0.89 | 0.001 | 0.71 |

| Dyadic coping → Partner coping | 0.87 | 0.001 | 3.99 |

| Dyadic coping → Self-coping | 0.51 | 0.001 | 1.87 |

| Infertility stress → Relationship concern | 0.76 | 0.001 | 1.23 |

| Infertility stress → Sexual concern | 0.68 | 0.001 | 1.08 |

| Infertility stress → Need for parenthood | 0.47 | 0.001 | 1.05 |

The results indicated that dyadic coping had a positive and significant effect on relational resilience (β = 0.67, P < 0.001), and relational resilience had a negative and significant effect on infertility stress (β = -0.51, P < 0.001). Relational resilience was positively and significantly associated with all its subscales (union, actor, spirituality, and partner), while dyadic coping was positively and significantly related to its subscales, self-coping and partner coping. Furthermore, infertility stress was positively and significantly associated with all its components, including social concern, relationship concern, sexual concern, and need for parenthood. These findings support the good fit of the model and confirm the significance of the hypothesized relationships among the main research variables.

According to Table 6, the standardized estimate of the indirect effect of dyadic coping on infertility stress, with lower and upper limits of -0.44 and -0.15, respectively, was -0.30* (based on bootstrap sampling, n = 2000, confidence level = 0.05, P = 0.008). This indicates a significant indirect effect of positive dyadic coping on infertility stress via relational resilience.

| Variables | Standard Estimate | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect of dyadic coping on infertility stress | -0.30 a | -0.44 | -0.15 | 0.008 |

a P < 0.05.

5. Discussion

The findings of this research demonstrated that relational resilience can mediate the relationship between positive dyadic coping and infertility stress. Consistent with the present results, a negative relationship between dyadic coping and infertility stress has been reported in other studies (30). Other aspects investigated in this study have also been validated by previous research, such as the positive association between dyadic coping and relational resilience (29, 31, 32), and the negative association between relational resilience and infertility stress (33). Zhao et al. found that psychological resilience is negatively correlated with distress and social avoidance and, to some extent, mediates the relationship between these factors and stigma in infertile patients (34). Psychological resilience can reduce patients' psychological problems and the negative effect of stigma on psychological distress and social avoidance.

In explaining these relationships, given the protective role of relational resilience during stressful events, creating favorable conditions to enhance relational resilience can improve the relationship between dyadic coping and infertility stress. Individuals who utilize positive and shared dyadic coping strategies to manage stressful situations typically have higher relational resilience. Employing adaptive coping strategies helps infertile women manage the challenges of this condition and enhances their psychological well-being, while maladaptive coping is considered a risk factor that diminishes resilience. Positive dyadic coping strategies adopted by infertile women and their husbands during stress lead to better relational resilience. This improvement in communication follows the acceptance and adaptation to their circumstances, helping to alleviate the concerns of infertile women.

Infertility is often accompanied by stigmatization, financial and economic stressors, and family pressures, all of which can significantly increase stress among infertile women. Breitenstein et al. demonstrated the pivotal role of dyadic coping in moderating the harmful effects of stress in young couples. Depending on the coping strategy utilized, it can influence both partners' relational resilience. Indeed, positive dyadic coping strategies foster relational resilience by enhancing couple cooperation, intimacy, and empathy. As relational resilience increases, couples' resistance to adversity improves, and their adaptive abilities are enhanced. This flexibility helps couples maintain compatibility in stressful circumstances (35).

In this study, to achieve better model fit, the 'Rejection of a child-free lifestyle' subscale was removed. This omission means the construct is not fully representative of the theoretical concept and should be considered when interpreting the findings. Another limitation was the difficulty of data collection due to the private nature of infertility in Iranian society. As all data were collected via self-report questionnaires, data accuracy could not be fully controlled. Additionally, the length of the questionnaires and participant fatigue may have influenced the results. Since this study included only infertile women, future research should involve infertile couples. Given the limitations of quantitative research in capturing all concerns of infertile individuals, qualitative studies are recommended for deeper insights. Considering the psychological challenges faced by infertile people, including infertility stress, it is suggested that relevant experts identify affected individuals and refer them for individual and group psychological services. Finally, given the high infertility rate in Iran, it is recommended that training workshops be conducted in infertility research centers to reduce stress and enhance coping and relational resilience among infertile people.

According to the results, positive dyadic coping can affect relational resilience and consequently reduce infertility stress. Therefore, infertility clinics should provide training in dyadic coping to infertile couples in addition to physical treatments. Such training may also facilitate physical treatment outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

When a wife experiences a stressor such as infertility, dyadic coping can bring the couple closer. Dyadic coping is an important strategy for managing stress, preventing the cooling of family relationships. By employing such strategies, couples can suppress infertility stress. Positive dyadic coping strategies help infertile women increase relational tolerance and reduce tension and stress.