1. Background

Suicidal ideation (SI), referring to persistent thoughts of ending one’s life, represents a significant public health concern (1). Research suggests that approximately 12% of individuals experiencing SI may attempt suicide within a five-year period (2). Globally, about 10% of the general population report SI, with rates reaching up to 20% among students (3, 4). Among the various psychological factors associated with SI, loneliness has emerged as a particularly salient issue (5). Defined as the perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social connections, loneliness is not limited to clinical populations but is increasingly prevalent among university students and young adults (6-8). Although SI and loneliness are distinct concepts, they are closely related (9, 10). Numerous studies (11, 12) have confirmed a positive correlation between them, suggesting they may share common underlying mechanisms.

Based on existing literature, social anxiety (SA) appears to play a significant role in the development of both SI and loneliness. The SA is characterized by a persistent fear of being negatively judged in social situations and affects approximately 12.1% of individuals at some point in their lives (13, 14). While loneliness has been associated with various psychiatric conditions, the connection appears particularly robust in the context of SA (15). Also, available evidence indicates that up to one-third of individuals with SA may experience SI, with prevalence estimates around 16% (16, 17). According to the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS), SI is more likely to arise when individuals perceive themselves as burdensome (perceived burdensomeness) and feel alienated from others (thwarted belongingness) (18-20). Those with SA are particularly vulnerable to these perceptions, given their tendency to avoid social interactions and the resulting exacerbation of feelings of disconnection (21). Furthermore, cognitive models (22-25) suggest that maladaptive beliefs and distorted interpretations of social experiences, often present in individuals with SA, may contribute to difficulties in establishing and maintaining meaningful relationships, thereby intensifying loneliness and elevating the risk of SI (26-28).

In the study by Liu et al. (4), it was shown that 45.7% of students had various degrees of SA problems. Even subclinical levels of SA have been linked to significant psychological distress, emphasizing the importance of viewing SA along a continuum rather than as a categorical diagnosis (29-32). This aligns with dimensional approaches to psychopathology, which emphasize the importance of identifying thresholds along the symptom continuum to better detect those who may benefit from early intervention (33).

Although several studies (28, 34) have explored the association between SA and SI, research focusing on Iranian populations remains limited. This is especially important given that SI is shaped by psychological, cultural, and economic factors (35), and growing evidence (36, 37) shows a high prevalence of both SA and SI among Iranian university students. Therefore, further investigations on the relationship between these variables in the Iranian population are necessary.

Additionally, the emotional distress linked to SA may increase reliance on maladaptive coping mechanisms such as dissociative experiences (DE) (38-40). The DE, defined as a disruption in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, or perception, often emerges as a defensive response to overwhelming stress (13). These experiences can range from mild episodes to severe clinical disorders, with lifetime prevalence rates estimated at 1 - 2% in the general population and approximately 11.4% among university students (13, 41). Although research on DE has traditionally concentrated on clinical populations, recent studies (38, 39) highlight its relevance in non-clinical groups as well.

Therefore, findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of SA may be more prone to DE in response to perceived distress (38, 39). On the other hand, DE has been conceptualized as both a reaction to psychological pain and a contributor to increased emotional suffering (42, 43). In particular, DE can amplify distress and heighten vulnerability to SI by disrupting one’s sense of reality and fostering a sense of detachment from others (42, 44). Consequently, DE may play a role in the development of loneliness and SI by undermining social functioning and impairing emotional regulation (42, 44-47). Specifically, DE has been linked to reduced use of adaptive strategies such as cognitive reappraisal and increased reliance on maladaptive strategies like emotional suppression, both of which are associated with diminished social support seeking and intensified loneliness (46, 47). Taken together, this body of evidence suggests that DE may undermine interpersonal connections, deepen experiences of loneliness, and heighten the risk of SI as a means of escaping psychological pain (42, 48, 49). Although previous research has examined the relationships between SA, loneliness, and SI individually, the potential mediating role of DE remains insufficiently explored. Clarifying these relationships could inform the development of more effective psychological interventions targeting university students and other at-risk groups.

2. Objectives

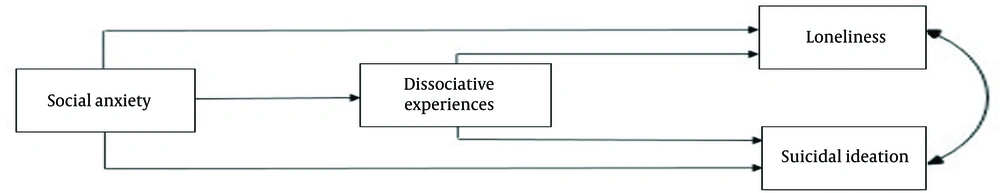

The present study aims to examine the mediating role of DE in the relationships between SA, SI, and loneliness (Figure 1).

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The statistical population consisted of undergraduate and graduate students of the Valiasr Complex of Islamic Azad University, South Tehran Branch in the academic year 2022 - 2023. To minimize selection bias, we employed a cluster random sampling method. Based on this method, first faculties and then classes (according to the ratio of the number of students in each faculty to the sample size) were selected from the Valiasr Complex, and all the students of those classes were considered as the research sample. A total of 340 students participated in the research, of which 28 students were excluded from the sample during screening, and the data of 312 students (107 men, 205 women) were included in the analysis. The age range of participants was 18 to 45 years (21.16 ± 4.87). Among them, 275 were single and 37 were married.

3.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

Participants eligible for inclusion were undergraduate and graduate students of the Valiasr Complex of Islamic Azad University, South Tehran Branch in the academic year 2022 - 2023, who provided informed consent to participate in the study.

3.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Individuals were excluded if they withdrew their consent at any point during the study, failed to fully complete the questionnaires, or self-reported serious medical or psychiatric conditions on the demographic information form.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Depression Symptoms Index - Suicidality Subscale

The Depression Symptoms Index - Suicidality Subscale (DSI-SS) is a scale used to measure SI over the past two weeks, first developed by Joiner et al. (50) from a larger questionnaire named the Hopelessness Depression Symptoms Questionnaire (51). The DSI-SS assesses the frequency, intensity, and controllability of suicidal thoughts and behaviors using four items. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 3 (51). The Persian version of the DSI-SS showed good internal consistency (α = 0.89) in an Iranian college student sample (52). In this research, Cronbach's alpha was 0.892.

3.2.2. Dissociative Experiences Scale II

This scale consists of 28 items that include three underlying factors: (1) Dissociative amnesia; (2) absorption/imaginative involvement; (3) depersonalization/derealization (53). Responses are given on an 11-point scale from 0% (never happens to me) to 100% (always happens to me), by increments of 10. The average score of the 28 items is considered the total score (54). The Persian version of the Dissociative Experiences Scale II (DES-II) has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in both clinical and non-clinical Iranian samples. Specifically, it showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95), high item-total correlations, and good split-half reliability (R = 0.892), indicating its appropriateness for use in Iranian populations (55). In this research, Cronbach's alpha was 0.930.

3.2.3. Loneliness Scale III, University of California

This scale consists of 20 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Items numbered 1, 5, 6, 9, 10, 15, 16, 19, and 20 are scored inversely (56). This scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the Iranian sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91), and strong test-retest reliability over a one-month interval, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.93, P < 0.001 (57). In this research, Cronbach's alpha was 0.888.

3.2.4. Social Anxiety Inventory

This is a 17-item self-measurement scale that has three subscales: (1) Fear, (2) avoidance, and (3) physiological discomfort. Each item is rated based on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) (58). The reliability and validity of this inventory were supported by Dogaheh (59) in a non-clinical Iranian sample, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 and 2-week test-retest reliability of 0.89. In this research, Cronbach's alpha was 0.894.

3.3. Procedure

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran Branch (IR.IAU.CTB.REC.1402.022). To complete the research questionnaires, we attended the selected classes and, after a brief explanation about the objectives of the research, the confidentiality, and anonymity of the questionnaires, we asked the students to complete the questionnaires if they were satisfied. Students were free to leave the research at any stage of completing the questionnaire. It should be noted that no incentives or rewards were given to the participants, and they participated in the research voluntarily.

3.4. Statistical Analyses

Data analysis was conducted using the path analysis method and descriptive statistics indicators such as mean, standard deviation, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, skewness, kurtosis, and Pearson Correlation Coefficient using SPSS-22 and Lisrel 8.8 software. It should be noted that the linear relationships between the variables were confirmed by drawing scatter plots. Before conducting path analysis, it was ensured that the basic assumptions (outliers, normality of data distribution, sample size, sphericity test, and non-multicollinearity) were met. Out of 340 distributed questionnaires, 28 questionnaires were excluded from the sample due to being incomplete or not matching the entry criteria. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, skewness, and kurtosis were used to determine the type of data distribution. As the results of Table 1 show, the significance level of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for all variables was more than 0.05, which indicates the normality of the distribution of the variables. According to Kline (60), who declared the minimum sample size in structural equation modeling to be 200, and also considering that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Index was equal to 0.895 (the coefficient of 0.6 is considered the minimum value necessary for analysis), the sample size of 312 students has fulfilled the requirement of sample size adequacy. The results of Bartlett's test of sphericity (P < 0.001 and ϰ2 = 3832.028) also indicate the assumption that the correlation matrix between the materials is not the same. Non-multicollinearity between variables was investigated using the Tolerance Index and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), which were obtained equally in both variables of SA and DE. These values were obtained as 0.954 for the Tolerance Index (which is greater than 0.1) and 1.049 for variance inflation (which is smaller than 10), indicating non-multicollinearity.

Abbreviations: K-S, Kolmogorov-Smirnov; SD, standard deviation; SA, social anxiety; SI, suicidal ideation; DE, dissociative experiences.

a P < 0.001.

4. Results

The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, skewness, kurtosis, means, and standard deviations of variables, and Pearson Correlation Coefficients are shown in Table 1.

Path analysis was used to determine the mediating role of DE in the relationship between SA, loneliness, and SI. Considering that the direct effect of SA on SI was not significant, this path was removed, and the fitness of the model was re-examined. Goodness of fit indices of the model indicate the appropriate fitness of the model: Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.98, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.96, Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.074, and the ratio of chi-square to the degree of freedom (ϰ2 ⁄ df) = 2.87. Since GFI, CFI, and NFI are greater than 0.9, RMSEA is smaller than 0.08 (61), and ϰ2 ⁄ df is smaller than 3 (60), the fitness of the model was confirmed. Therefore, the standardized coefficients of the total effects, direct effects, and bootstrapped indirect effects of the paths in the model were investigated (Table 2). The fitted model along with standard path coefficients is shown in Figure 2.

| Pathway | Total | 95% CI | Direct | 95% CI | Indirect | 95% CI | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA → DE | 0.22 a | 0.08 - 0.34 | 0.22 a | 0.08 - 0.34 | - | - | 0.11 |

| SA → loneliness | 0.49 b | 0.43 - 0.60 | 0.45 b | 0.40 - 0.56 | 0.042 b | 0.01 - 0.07 | 0.28 |

| SA → SI | 0.062 b | 0.02 - 0.11 | - | - | 0.062 b | 0.02 - 0.10 | 0.09 |

| DE → SI | 0.28 b | 0.14 - 0.36 | 0.28 b | 0.14 - 0.36 | - | - | 0.21 |

| DE → loneliness | 0.19 a | 0.07 - 0.27 | 0.19 a | 0.07 - 0.27 | - | - | 0.18 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SA, social anxiety; DE, dissociative experiences; SI, suicidal ideation.

a P < 0.05.

b P < 0.01.

If the confidence interval (CI) does not include zero, the path coefficient is considered statistically significant at the chosen confidence level. Therefore, as shown in Table 2, the standard coefficients of all direct effects were significant. Also, the bootstrapped indirect effects coefficients indicate that DE can play a mediating role in the relationship between SA with loneliness and SI.

The results indicated that higher levels of SA were associated with greater DE (β = 0.22, P < 0.05). The SA also predicted higher levels of loneliness both directly (β = 0.45, P < 0.01) and indirectly through DE (β = 0.042, P < 0.01). The total effect of SA on loneliness was substantial (β = 0.49, P < 0.01). Although SA did not have a significant direct effect on SI, a significant indirect effect was observed through DE (β = 0.062, P < 0.01). The SA explained 11% of the variance in DE, 28% in loneliness, and 9% in SI. Additionally, DE accounted for 21% of the variance in SI and 18% in loneliness.

5. Discussion

The present study examined the mediating role of DE in the relationship between SA, SI, and loneliness. The results revealed a positive relationship between SA and SI, consistent with previous research (28, 34). However, path analysis indicated that the direct effect of SA on SI was not statistically significant.

This finding can be better understood through both interpersonal and cognitive perspectives (18, 20, 22, 23). Individuals with SA often hold negative beliefs about themselves and set unrealistically high standards, leading them to feel inadequate. This can generate a fear of disappointing others or a belief that their presence is unwanted, which contributes to SI (18, 19, 22). However, as Duffy et al. (19) point out, SA in non-clinical populations typically involves only mild concerns about being judged, which may not be intense enough to provoke feelings of burdensomeness or thwarted belongingness, two critical factors in SI, according to the interpersonal theory of suicide. This may explain why the direct link between SA and SI was not significant in this study. Therefore, the relationship between these variables might become clearer in clinical populations with more severe SA.

Although no direct effect was found, our findings suggest that SA may contribute to SI indirectly through DE. In line with previous studies (38, 39), since DE are a form of emotional suppression, SA can be effective in predicting DE even with not very intense arousal levels. Therefore, it is expected that the higher the severity of SA, the more people will use maladaptive strategies that are based on avoidance. As a result, when facing social stress, DE will be used as a defense against the threat caused by perceived negative evaluation (38, 40, 43). On the other hand, consistent with the findings of Foote et al. (62) and Keefe et al. (63), DE are linked to SI. While DE may provide temporary relief from psychological distress, it eventually becomes an ineffective coping strategy, reflecting an escape-oriented mindset rather than a problem-solving approach. This ongoing psychological vulnerability, especially under sustained emotional stress, can increase dissociative tendencies and contribute to the development of SI (42, 48, 64). The study also found a significant positive relationship between SA and loneliness, consistent with prior research (15, 26). From a cognitive perspective, loneliness often stems from internal experiences and perceptions of relational deficits (24). Dysfunctional beliefs and distorted cognitive processes, common among individuals with SA (22, 23), may lead them to perceive and evaluate relationships negatively, thus intensifying their loneliness.

Furthermore, DE also mediated the relationship between SA and loneliness. Individuals with SA may use DE as a coping mechanism during stress, but this strategy can disrupt interpersonal functioning by affecting cognition, emotion, and identity (45, 65, 66). For example, during depersonalization episodes, individuals may struggle to connect with others (65). Moreover, the uncontrollable nature of DE, along with its impact on memory, emotion, and self-concept, can induce deep shame, further hindering social interactions (66). Problems with recalling relational information also impair emotional connection (45), which in turn fosters loneliness. The DE can impair cognitive reappraisal, causing individuals to view social interactions more negatively, which intensifies loneliness and emotional distress by hindering their ability to connect with others (46, 47). These findings are consistent with prior studies linking DE to loneliness (49, 65, 66).

Finally, DE were found to mediate the relationship between SA and both SI and loneliness. The DE may act as a maladaptive coping mechanism for managing the emotional distress associated with SA, where SI appear as an escape from overwhelming psychological pain and deepen the experience of loneliness (39, 43, 48, 49, 64). These findings highlight the importance of adopting dimensional approaches to psychopathology, as even subclinical levels of SA may indicate psychological vulnerability (33). Identifying these thresholds can enable early intervention, potentially reducing the risk of developing more severe outcomes such as SI and loneliness.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of this research highlight the significant role of DE as a maladaptive strategy in the development of loneliness and SI among individuals with symptoms of SA. These results underscore the clinical importance of promoting adaptive emotion regulation strategies in individuals with SA (67), rather than relying on dissociative responses. Targeted interventions that address dysfunctional beliefs and encourage healthier coping strategies can help reduce maladaptive responses, including dissociative tendencies (68). Such interventions could play a crucial role in preventing loneliness and SI by fostering more effective emotional responses to social stressors in individuals suffering from SA.

5.2. Limitations

It is important to note that the cross-sectional design of this study limits our ability to infer causality. In addition, given evidence that DE both contribute to and result from other psychopathological symptoms (69), it may also exacerbate symptoms of SA. Our focus was on the non-clinical population from an academic unit, so the generalization of the results to clinical communities and other non-clinical groups is limited. Additionally, due to the random sampling method, the sample exhibited a gender imbalance, with a higher proportion of women, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Finally, we only considered SI as the most basic part of the suicide continuum.

5.3. Future Directions for Research

Longitudinal studies are recommended to better understand the direction of these relationships and whether DE acts as a predictor or consequence of SA. It is suggested that future research be conducted on the clinical population to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Addressing the gender imbalance in future research will also improve the applicability of the results. Furthermore, future studies should consider measuring suicide planning and suicide attempts to compare the relationships of the variables between the committed and non-committed suicide groups.

![The diagram of direct paths with standard coefficients [chi-square: 2.87, df: 1, P: 0.00128, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA): 0.074. Abbreviations: SA, social anxiety; DE, dissociative experiences; SI, suicidal ideation]. The diagram of direct paths with standard coefficients [chi-square: 2.87, df: 1, P: 0.00128, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA): 0.074. Abbreviations: SA, social anxiety; DE, dissociative experiences; SI, suicidal ideation].](https://services.brieflands.com/cdn/serve/3170d/26a5249a6ffb9ba89839f4e6ed3ccf171a485589/ijpbs-19-3-158485-i002-preview.webp)