1. Background

Research on dynamic psychotherapy for depression has followed two main approaches: Interventions guided by general psychodynamic manuals and those based on depression-specific manuals. General manuals, such as those by Luborsky (1), Malan (2), and Davanloo (3), provide flexible frameworks that allow therapists to tailor treatment to individual needs. For example, Luborsky (1) emphasizes the therapeutic relationship and core conflicts; Malan (2) focuses on transference and countertransference; and Davanloo (3) developed intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) to rapidly access unconscious emotions and defenses.

A substantial body of evidence supports the efficacy of short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (STPP) guided by such manuals. Meta-analyses by Driessen et al. (4-9) show that STPP significantly reduces depressive symptoms, with outcomes comparable to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy, and sustained benefits at follow-up. Further studies (10, 11) highlight mechanisms such as emotional regulation, insight into unconscious conflict, and therapeutic alliance as key to STPP's effectiveness. A Cochrane review by Abbass et al. (12), along with Shedler’s review (13), further confirms STPP’s efficacy across various mental health conditions. Meta-analytic work by Leichsenring (14) also provides comparative insights between psychodynamic therapy and CBT.

Despite advances in psychodynamic treatment research, a critical need persists for approaches that directly address the underlying psychological mechanisms of depression. The manual developed by Busch et al. (2015) is distinctive in that it is not only grounded in psychodynamic theory but also specifically designed for the treatment of depression — unlike broader psychodynamic frameworks that address a wide range of conditions. What distinguishes this manual is its precise articulation of three psychological dynamics that are both empirically validated and clinically significant — narcissistic vulnerability, conflicted anger, and perfectionism — that are consistently observed in depressed patients. By operationalizing these dynamics within a structured therapeutic framework, the Busch et al. manual provides a coherent and testable model for depression-specific psychodynamic treatment.

Busch et al.'s (15, 16) approach represents a promising contribution to dynamic treatments for depression, offering theoretically grounded strategies to address core depressive processes. It aligns with Shedler’s (13) broader findings on the value of psychodynamic interventions and is supported by related work on narcissism and depression (17), as well as developmental perspectives from Blatt (18) and Fonagy and Luyten (19). In particular, its emphasis on narcissistic vulnerability provides a clinically nuanced understanding of internalized anger, rejection sensitivity, and harsh self-criticism, which are often underexplored in other therapeutic modalities. Accordingly, investigating the application of this manual is warranted not only due to its limited representation in empirical research but also because of its theoretical rigor and its potential to advance our understanding of psychodynamic mechanisms specific to depression.

2. Objectives

The present study examines the efficacy of a STDP intervention based on Busch et al.'s manual in treating moderate to severe depression in individuals diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD). We hypothesize that the intervention reduces depressive symptoms by improving problematic relational patterns related to narcissistic vulnerability — such as insecure attachment, egocentricity, and alienation — and enhances overall daily functioning. Given that Busch’s manual offers a structured clinical guide rooted in psychoanalytic theory and specifically tailored to the psychological vulnerabilities associated with depression, it holds promise as a targeted treatment approach. However, despite its theoretical strengths, this manual has not yet been thoroughly tested in clinical research. Thus, conducting an empirical study to evaluate its efficacy is both timely and necessary, as it may provide much-needed evidence for a manualized psychodynamic intervention that addresses the specific intrapsychic and interpersonal dynamics of depression.

3. Methods

3.1. Participant Selection

Five participants were recruited from the waiting list of the psychiatry clinic affiliated with Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (Zanjan, Iran). These participants had not yet received conventional treatment for depression and were not taking antidepressant medication during the course of the study. Inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) A score exceeding 14 on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), (2) a diagnosis of MDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), (3) no current diagnosis of psychosis or substance use disorder, and (4) completion of a written informed consent form.

Participants who met the initial criterion of an HDRS score > 14 were evaluated by a psychiatrist to confirm the diagnosis of MDD and ensure they met all inclusion criteria. Subsequently, a trained clinical psychologist administered a structured clinical interview based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (SCID-5) to definitively establish the diagnosis of MDD. Exclusion criteria included the presence of psychotic symptoms, substance use disorder, and absence from three or more therapy sessions. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 24 years. The demographic characteristics are given in Table 1.

| Patients | Age | Gender | Duration of Illness | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG | 24 | Male | 6 mo | MDD |

| NE | 23 | Female | 4 year dysthymic symptoms + MDD symptoms at time of interview | Double depression |

| FA | 20 | Female | 8 mo | MDD |

| AE | 20 | Female | 6 mo | MDD |

| SK | 19 | Female | 1 y | MDD |

Abbreviation: MDD, major depressive disorder.

To ensure uniformity of treatment, we shortened the number of sessions in the original protocol so that all participants received the same intervention: A minimum of 24 sessions of psychodynamic psychotherapy for depression. This adjustment is specified in the treatment protocol. Importantly, while we later divided the course of therapy into two halves for the purposes of statistical analysis, no such division existed in the implementation of the protocol itself. The rationale for dividing the treatment into two halves is that research (20, 21) on psychodynamic psychotherapy indicates symptoms may initially worsen in early sessions as defenses emerge. Thus, comparing the first and second halves of treatment may provide clearer insight into this process. All participants received the intervention as a continuous treatment. Given the single-case, multiple-baseline design and the absence of a control group, outcome evaluators were kept blind to the study hypotheses to minimize bias.

3.2. Measures

We employed the HDRS as a validated measure to systematically evaluate the severity of depression symptoms exhibited by participants. Additionally, the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was utilized to quantify the extent of functional impairment attributable to psychopathological symptoms. Furthermore, the Bell Object Relations Inventory (BORRI) was employed to explore potential mediators of change throughout the intervention. Together, these assessment tools offered a comprehensive framework for evaluating the multifaceted impact of interventions on depression severity, functional impairment, and underlying relational dynamics.

3.2.1. The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

The HDRS, developed by Hamilton in 1960, consists of 21 questions designed to assess the severity of depression in patients (22). During an interview, a trained clinician evaluates the patient's responses and assigns scores that contribute to a total score. The scale categorizes depression severity as follows: Zero to seven indicates a normal range (no depression); 8 - 13 suggests mild depression; 14 - 18 indicates moderate depression; 19 - 22 signifies severe depression; and scores equal to or greater than 23 indicate very severe depression. The HDRS is widely recognized for its reliability (23) and validity (24), making it a valuable tool in both research and clinical practice for monitoring treatment progress.

3.2.2. Sheehan Disability Scale

The SDS, developed by Sheehan et al. (25, 26), is a concise self-assessment instrument designed to quantify the impact of health conditions on an individual's daily activities. It focuses specifically on three key domains: Work/school, social life, and family life. In each domain, respondents rate the extent of impairment they experience using a scale ranging from 0 (no impairment) to 10 (extreme impairment). By aggregating these domain scores, clinicians and researchers derive a total score that reflects the overall functional disability caused by health issues. Higher total scores indicate greater levels of impairment across the assessed domains. Recent studies (27) have demonstrated the SDS's reliability as a tool for accurately measuring functional impairment. Its structured approach makes it valuable in both clinical settings and research environments, offering a standardized means to assess and monitor the impact of health conditions on daily life activities.

3.2.3. Bell Object Relations Inventory

The BORRI is a comprehensive self-assessment questionnaire designed to evaluate individuals' capacities in object relations and ego functioning. Object relations refer to how individuals perceive and interact with others, while ego functioning relates to their overall sense of self and how they manage interpersonal relationships. The BORRI specifically examines four critical aspects of object relations:

- Alienation: Feelings of isolation or estrangement from others

- Attachment insecurity: Concerns and anxieties regarding interpersonal relationships

- Egocentricity: Degree of self-centeredness or difficulty considering others' perspectives

- Social incompetence: Challenges in effectively engaging in social interactions

Studies conducted by Bell et al. (28, 29) have demonstrated the BORRI's reliability. They have consistently found strong internal consistency, typically indicated by Cronbach's alpha coefficients exceeding 0.70 for both adult and adolescent versions of the inventory. This statistical measure suggests that the items within each subscale of the BORRI reliably assess related concepts, providing clinicians and researchers with a robust tool to evaluate and understand individuals' object relations and ego functioning.

3.3. Design

The study utilized an ABA single-case design with a multiple baseline across participants. In this design, phase A represented the baseline periods (A1), phase B denoted the intervention phase, and phase A2 served as a follow-up assessment. Baseline phases (A1) were staggered among participants, with each subsequent participant commencing their baseline phase two weeks later than the previous participant. This approach resulted in progressively longer baseline periods across participants. Weekly and monthly assessment tools were employed throughout the study.

The HDRS was administered weekly across all phases — baseline (A1), intervention (B), and follow-up (A2) — to monitor depressive symptoms. Additionally, the SDS and the BORRI were administered monthly during the baseline phase (A1), intervention phase (B), and follow-up phase (A2). These assessments provided comprehensive data on participant progress and treatment outcomes over the course of the study.

The treatment was conducted by the first author in accordance with the manual. Initial assessments, including diagnostic interviews using the SCID and the administration of tests at designated time points, were carried out by independent assessors who were not involved in the treatment and were blinded to the study’s hypotheses and objectives.

3.4. Treatment Protocol

Busch et al. (16) developed a manualized psychoanalytic treatment for depression. The original protocol consisted of up to 40 bi-weekly sessions delivered over a 20-week period. In our adaptation, we implemented the treatment in 24 sessions, meeting twice weekly. Five participants underwent a total of 24 therapy sessions, administered twice weekly by a single psychotherapist. The psychotherapist's involvement during the research intervention was exclusively dedicated to these participants. The treatment adheres to a three-phase structure.

3.4.1. Phase 1: Initial Treatment

The first phase emphasizes building rapport with the patient and establishing the root cause of their depression. The therapist explores the patient's symptomatology, stressors, and past experiences to identify underlying conflicts contributing to the depression. Additionally, common emotional patterns associated with depression, such as anger, guilt, shame, and idealization, are discussed. By the conclusion of this phase, the therapist aims to alleviate the patient's symptoms, develop a shared understanding of the depression's etiology, and establish a strong foundation for further therapeutic work.

3.4.2. Phase 2: Middle Treatment

The middle phase focuses on reducing the patient's vulnerability to depression. Through exploration of the patient's internal world and its interaction with others, the therapist aims to equip the patient with skills to manage difficult emotions and improve their relationships. Therapeutic work centers on exploring past and present conflicts, managing emotions arising during sessions, and fostering a deeper understanding of these issues. Successful completion of this phase would translate to the patient experiencing less depression triggered by criticism or loss, improved anger management, reduced guilt, and healthier relationships.

3.4.3. Phase 3: Termination

Termination provides a crucial opportunity for further exploration of depression's dynamics, particularly as they manifest in the transference. Key areas of focus include:

- Understanding the patient's feelings regarding the therapist's loss and treatment conclusion

- Coping with the sense of narcissistic injury associated with fantasies of a prolonged relationship with the therapist

- Processing anger towards the therapist regarding termination and treatment limitations

Expected responses during termination:

- Possible temporary intensification of depressive symptoms as termination nears, prompting the patient to confront powerful resurgences of feelings related to loss and separation.

- Enhanced capacity to manage loss and narcissistic injury

- More effective utilization of anger with less self-directed aggression

- Reduced guilt and diminished need for self-punishment.

3.5. Data Analysis

Given the single-subject design of this study, the statistical analysis focused on assessing changes within each participant's scores. Trend line analysis was employed solely for the HDRS scores to visually depict the direction and potential pattern of change. The primary analysis method, however, relied on the Reliable Change Index (RCI) to evaluate changes in all three scales (HDRS, SDS, and BORRTI).

The RCI was calculated for each subject using the formula proposed by Christensen and Mendoza (30):

Where RC = Reliable change, X1 = Pre-test score, X2 = Post-test score, and SE = Standard error of measurement, the SE is a critical component of the RCI formula. It reflects the inherent variability in the measure and was determined using the established test-retest reliability coefficient or the internal consistency coefficient reported in the literature for each scale: The HDRS = 0.85 (31), SDS = 0.73 (32), and BORRTI subscales = 0.70 (28, 29). Jacobson and Truax (33) suggested an absolute RCI value of 1.96 or higher to indicate clinically significant change.

To increase the precision of the analysis, the intervention phase was divided into two equal periods: An initial and a final half. As a result, the total number of treatment sessions (24) was split in half. The data collected during the first 12 sessions was then compared to the data collected during the last 12 sessions. The results of the RCI analysis for each subject are presented in Table 2.

| Subjects and Measures | Pre-test (Baseline, Raw Scores) | Post-test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Half of Treatment | Second Half of Treatment | Follow-up | |||||

| Raw Scores | RCI | Raw Scores | RCI | Raw Scores | RCI | ||

| First subject: SG | |||||||

| HDRS | 23, 19, 31, 21 | 24, 24, 25, 15, 12, 23, 9, 17, 17 | -5.95 | 18, 17, 16, 16, 17, 14, 12, 8, 5 | -11.58 | 4, 4, 5, 6, 5, 7 | -21.58 |

| SDS | 22 | 18, 7 | -16.17 | 5, 5 | -19.32 | 5, 7 | -18.18 |

| BORRTI | |||||||

| ALN | 3, 2 | 2, 2 | -0.61 | 2, 2 | -0.61 | 3 | -0.61 |

| IA | 7, 9 | 8, 6 | -1.35 | 7, 6 | -2.03 | 6 | -2.70 |

| EGC | 15, 9 | 12, 7 | -3.38 | 10, 7 | -4.73 | 9 | -4.05 |

| SI | 13, 10 | 10, 6 | -5.15 | 10, 8 | -3.68 | 10 | -2.21 |

| Second subject: NE | |||||||

| HDRS | 23, 22, 23, 21, 22, 21 | 21, 19, 17, 15, 15, 19, 16, 15 | -5.74 | 12, 14, 14, 13, 12, 11, 8, 10 | -12.06 | 12, 12, 10, 13, 14, 15 | -10.99 |

| SDS | 25, 22 | 18, 20 | -5.11 | 23, 14 | -5.68 | 17 | -7.39 |

| BORRTI | |||||||

| ALN | 3, 3 | 4, 4 | 1.22 | 4, 4 | 1.22 | 5 | 2.44 |

| IA | 7, 6 | 5, 5 | -2.03 | 4, 5 | -2.07 | 6 | -0.68 |

| EGC | 9, 8 | 9, 9 | 0.68 | 9, 9 | 0.68 | 12 | 4.73 |

| SI | 9, 9 | 7, 9 | -1.47 | 10, 9 | 0.74 | 10 | 1.47 |

| Third subject: FA | |||||||

| HDRS | 33, 29, 37, 35, 34, 31, 32, 31 | 37, 18, 23, 19, 17, 18, 17 | -13.49 | 21, 15, 12, 13, 21, 17 | -19.12 | 13, 12, 13, 19, 17, 16 | -20.88 |

| SDS | 38, 39, 40 | 39, 44 | 2.84 | 33, 37 | -4.55 | 22 | -19.32 |

| BORRTI | |||||||

| ALN | 4, 2, 4 | 4, 3 | 0.21 | 3 | -.40 | 3 | -0.40 |

| IA | 7, 8, 10 | 9, 11 | 2.26 | 11 | 3.61 | 10 | 2.26 |

| EGC | 14, 13, 16 | 16, 15 | 1.58 | 17 | 3.61 | 15 | 0.91 |

| SI | 14, 11, 14 | 17, 14 | 3.68 | 17 | 5.88 | 15 | 2.94 |

| Fourth subject: AE | |||||||

| HDRS | 28, 21, 28, 27, 28, 31, 34, 26 | 36, 28, 27, 21, 19, 18 | -3.47 | 20, 15, 13, 20, 25, 22 | -10.14 | 16, 13, 15, 16, 12, 13 | -16.02 |

| SDS | 28, 19 | 20, 31 | 2.27 | 9. 20 | -10.23 | 25 | -5.68 |

| BORRTI | |||||||

| ALN | 3, 3, 4 | 4, 4 | 0.82 | 4 | 0.82 | 5 | 2.04 |

| IA | 7, 6, 5 | 5, 5 | -1.35 | 5 | -1.35 | 6 | 0 |

| EGC | 9, 8, 9 | 9, 9 | 0.46 | 9 | 0.46 | 12 | 4.51 |

| SI | 10, 10, 9 | 11, 9 | 0.50 | 11 | 1.97 | 13 | 4.91 |

| Fifth subject: SK | |||||||

| HDRS | 30, 29, 30, 28 | 22, 23, 18, 17 | -10.88 | 16, 16, 16, 17 | -15.29 | 16, 7, 15, 17 | -15.29 |

| SDS | 26 | 24, 24, 22 | -3.03 | 21, 22, 20 | -5.68 | 20, 20 | -6.82 |

| BORRTI | |||||||

| ALN | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | -1.18 | 2 | -1.18 |

| IA | 7 | 6 | -1.35 | 6 | -1.35 | 5 | -2.70 |

| EGC | 13 | 14 | 1.35 | 11 | -2.70 | 11 | -2.70 |

| SI | 12 | 13 | 1.47 | 11 | -1.47 | 10 | -2.94 |

Abbreviations: RCI, Reliable Change Index; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; BORRI, Bell Object Relations Inventory; ALN, Alienation; IA, Insecure Attachment; EGC, Egocentricity; SI, Social Incompetence.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The research proposal ensured informed consent was obtained through a written document, along with a full explanation provided to the patients. Participation in the study incurred no costs for the patients, and the confidentiality of their information was strictly maintained. Approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Zanjan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZUMS.REC.1401.345) and registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20230228057566N1).

4. Results

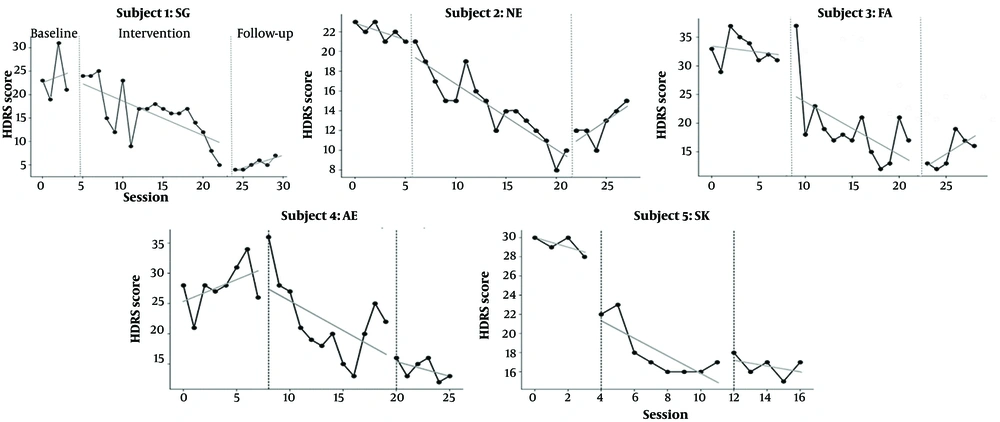

Figure 1 depicts the trends in HDRS scores across the three phases: Baseline, intervention, and follow-up (the trend line description can be found in the margin of Figure 1). Table 2 summarizes the data, revealing a general decline in mean HDRS scores across all subjects from baseline to follow-up. This suggests a positive intervention effect on depression symptoms.

Trends of changes Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) scores in three phases. Subject SG — During baseline SG’s HDRS scores fluctuate in the mid-20s to mid-30s. With the start of the intervention SG experiences a relatively sharp initial decline in scores followed by a more gradual continued decrease across sessions. At follow-up SG’s scores remain well below baseline, indicating a sustained improvement. Subject NE — NE shows moderately high baseline scores with some fluctuation. During the intervention there is a steady overall decline, though the trajectory includes short within-phase rises and falls. At the end of the intervention NE reaches one of the lowest scores observed, but shows a small rebound at follow-up, so that the follow-up level, while lower than many baseline points, is slightly higher than the immediate post-intervention nadir. Subject FA — FA’s baseline HDRS scores are relatively high and somewhat variable. Throughout the intervention FA exhibits a consistent downward trend with fewer abrupt fluctuations than some other subjects. However, FA’s score rebounds slightly during follow-up, raising questions about the durability of the effect for this subject. Subject AE — AE begins with baseline scores in the mid-to-high range and exhibits a slight initial increase at the very start of intervention followed by a sustained and relatively steady decline across the remainder of treatment. AE’s follow-up scores remain lower than baseline, suggesting a durable response. Subject SK — SK shows high baseline scores but a marked and rapid decrease early in the intervention that levels into a low, relatively stable trajectory for the remainder of treatment. At follow-up SK’s scores remain at these low levels, indicating a strong and sustained treatment response.

The largest decrease in HDRS scores is observed in the SG subject, from 23.5 at baseline to 5.16 at follow-up, indicating a significant improvement in depression symptoms. The NE subject also demonstrates a decrease in HDRS scores, from 22 at baseline to 12.66 at follow-up, suggesting that the intervention benefitted this subject as well. Similarly, the FA subject shows a decrease in HDRS scores, from 32.75 at baseline to 15 at follow-up, indicative of a positive response to the intervention. Likewise, the AE subject exhibits a decrease in HDRS scores, from 27.78 at baseline to 14.16 at follow-up, suggesting the intervention's helpfulness. Finally, the SK subject shows a decrease in HDRS scores, from 29.25 at baseline to 16.25 at follow-up, indicating a positive impact of the intervention.

Before conducting the RCI analysis, it is important to note that, as mentioned earlier, the pre-test score is subtracted from the post-test score in the relevant formula. Therefore, if the post-test score is lower than the pre-test score, the resulting index will be negative and vice versa. Consequently, it is expected that the post-test scores will decrease, and thus, a negative RCI score is desirable. As previously mentioned, a value greater than 1.96 indicates clinical significance. To better compare the RCIs of the intervention phase with baseline and follow-up, the intervention period was divided into two halves (first and second).

The results of the RCI analysis of HDRS showed that all five patients had clinically significant changes in both the first and second halves of the intervention. All five patients maintained this change at a clinically significant level after the treatment discontinuation period (follow-up, Table 2). Changes in SDS scores using the RCI are presented for each phase separately.

1. First half of intervention:

- Responders: SG showed the most significant improvement (RCI of -16.17), followed by NE with moderate improvement (RCI of -5.11) and SK with moderate improvement (RCI of -3.03).

- Non-responders: FA and AE did not show initial improvement. Scores worsened for FA (RCI of 2.84) and showed a modest worsening for AE (RCI of 2.27).

2. Second half of intervention:

- Continued improvement: SG maintained a strong positive response (RCI of -19.32), with SK also showing continued improvement (RCI of -5.68). NE exhibited slight additional improvement (RCI of -5.68).

- Turning point: FA showed a remarkable improvement (RCI of -4.55) compared to the first half, suggesting the intervention might have had delayed effects. AE had a substantial improvement (RCI of -10.23), potentially due to a specific aspect of the intervention in the second half.

3. Follow-up:

- Sustained improvement: SG and SK maintained their improvements, with scores close to the second intervention phase (RCI of -18.18 and -6.82, respectively). NE showed further improvement (RCI of -7.39) even without additional intervention.

- Positive outcomes: FA reached a score lower than baseline (RCI of -19.32), suggesting a delayed treatment effect or possible influence of other factors. AE showed a slight increase from the second intervention phase (RCI of 1.70) but still maintained a significant improvement compared to baseline. This could indicate some minor regression.

An examination of individual patterns within the data (Table 2) yields the following general conclusions regarding the RCI analysis of BORRI subscale scores:

- Insecure attachment: Significant improvement in this domain was observed in all subjects except SK. This suggests that the intervention may be efficacious in addressing difficulties associated with forming trusting and stable relationships.

- Egocentricity: NE and FA demonstrated significant improvements, indicating a potential for the intervention to reduce self-centeredness and enhance attentiveness to the needs of others.

- Social incompetence: While NE and FA exhibited sustained improvement, SG and SK displayed an initial positive change followed by a decline. This finding suggests that the intervention's effectiveness in fostering social skills and comfort may vary across individuals.

- Alienation: No consistent pattern of change was evident across subjects, implying that the intervention may not have a significant impact on feelings of isolation or disconnection.

5. Discussion

This single-subject study investigating a STDP intervention based on Busch et al.'s manual yielded promising results. The findings suggest that the 24-session intervention effectively reduced depressive symptoms and improved daily functioning in five individuals diagnosed with MDD. The significant reduction in HDRS scores throughout the intervention and follow-up phases supports the intervention's ability to alleviate depressive symptoms. This aligns with the growing body of research supporting the efficacy of STDP in treating depression.

For example, Abbass at al. (12) conducted a meta-analysis revealing significant reductions in depressive symptoms following STDP, with improvements sustained during follow-up periods. Similarly, Driessen et al. (7) conducted a meta-analysis of 54 studies, including 33 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with 3,946 participants, which demonstrated that STDP led to significant symptom reduction compared to control conditions, with these gains maintained or further enhanced at follow-up.

Our study assessed four types of object relations using the BORRI. Notably, a statistically significant decrease in insecure attachment scores was observed in most patients (80%). By aligning the BORRI's concept of insecure attachment with the construct of narcissistic vulnerability as presented in the Busch et al. (15, 16) manual, particularly their emphasis on interpreting narcissistic vulnerability in clinical settings, we propose a stronger mediating effect of insecure attachment in reducing depression severity. In other words, our findings suggest that improvements in insecure attachment are associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms.

According to the BORRI manual, individuals with high scores on the insecure attachment subscale are likely to be highly sensitive to rejection and easily hurt by others. They may struggle with intimacy and closeness, and separations, losses, and loneliness are often unbearable. Such individuals commonly have neurotic concerns about being loved and accepted by others.

Busch et al. (15, 16) identified heightened sensitivity to criticism and rejection as a common feature among individuals experiencing depression, which stems from a fragile sense of self-worth — a core characteristic of narcissistic vulnerability. Even minor or constructive criticism can be perceived as a complete negation of their value, and rejection, whether in the form of social exclusion or perceived slights, can be devastating. Studies (34, 35) have consistently demonstrated that insecure attachment patterns formed in early childhood constitute a significant risk factor for the development of depression in adulthood. These findings further support the focus on relational patterns in STDP interventions for depression.

Horowitz et al. (36) investigated the implications of interpersonal problems and attachment styles for brief dynamic psychotherapy, while Travis et al. (37) found that a significant proportion of clients exhibited a change from an insecure to a secure attachment style following time-limited dynamic psychotherapy. Mullin at al. (38) demonstrated a positive association between improvements in object relations functioning during psychodynamic psychotherapy and adaptive changes in patient-reported symptomatology.

Our intervention resulted in a significant reduction in SDS scores, indicating its efficacy in improving daily functioning among individuals with depression. This finding aligns with the conclusions of Johansson et al. (39), who demonstrated that STDP led to substantial improvements in both depressive symptoms and functional impairment as measured by the SDS. Furthermore, the observed enhancement in daily functioning among patients with major depression following STDP is consistent with the findings reported in the meta-analysis by Driessen et al. (7).

However, our study differs from these previous investigations in terms of the specific assessment tools employed. While the studies in the Driessen et al. (7) meta-analysis primarily utilized the EuroQol instrument, our study incorporated the SDS (26), providing a more comprehensive evaluation of functional impairment. This distinction is crucial because the EuroQol assesses health-related quality of life across diverse health conditions, offering a broad perspective, while the SDS provides a more focused evaluation of functional limitations specifically associated with mental health problems.

5.1. Conclusions

This single-subject study provides preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of a brief dynamic psychotherapy intervention in reducing symptoms of depression and improving daily functioning in individuals with MDD. The intervention appears to work by targeting core relational difficulties associated with depression. These findings encourage further research on STDP as a promising treatment approach for depression.

5.2. Strengths

This research represents a novel approach by integrating a focus on narcissistic vulnerability within a psychodynamic framework for treating depression. The study's innovative focus on narcissistic vulnerability offers a unique perspective on treatment outcomes, potentially providing more robust evidence for its centrality in depression. By addressing narcissistic vulnerability directly, the intervention may lead to improved outcomes, helping to isolate the specific effect of this focus within the broader framework of psychodynamic therapy for depression.

5.3. Limitations

The single-subject design restricts the generalizability of the findings to a broader population, necessitating future research with larger and more diverse samples to confirm these results. Additionally, the study relied on self-report measures, which introduces potential bias. Incorporating clinician-rated assessments alongside self-report measures could strengthen future studies. Future research should employ comparative designs contrasting the specific psychodynamic therapy used in this research with alternative approaches that do not explicitly target narcissistic vulnerability. Incorporating a RCT design to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention is a widely accepted standard in this field.