1. Background

Risky behaviors can include a wide range of activities, such as smoking, alcohol and drug use, unprotected sexual practices, aggression, self-harm, suicide, and reckless driving (1). The prevalence of risky behaviors is notably higher among college students due to various biological, psychological, and social factors (2, 3). Smoking, using hookah, and suicide ideation have been identified as the most common risky activities among university students in Iran (4). Some theories attribute these actions to the underdevelopment of the brain's lobes, while others suggest that they stem from peer influence and modeling (2). One of the psychological processes that, according to the ego psychology framework (5), can predict the likelihood of risky behavior in various personalities is the ego's defense mechanisms. According to the ego psychology framework, defense mechanisms are defined as unconscious and semi-conscious strategies that individuals employ to manage distressing emotions, distort reality, and cope with various life stresses (5). These mechanisms are categorized into three groups: Neurotic mechanisms such as projection, immature mechanisms like acting out, and mature mechanisms including sublimation and humor (6). In contrast to mature defenses, the primary aim of immature defenses is to avoid experiencing uncomfortable emotions (7). Prior research has demonstrated that defense mechanisms exhibit varying associations with different mental disorders (8-10). For example, in the context of depression, mechanisms like identification and internalization are notably prevalent (9), whereas in obsessive-compulsive disorder, the mechanism of reaction formation holds greater significance (10). In the context of antisocial behaviors, acting out and projection play a more pronounced role (11-13). Prior research concerning risky behaviors, including reckless motorcycle operation (14), alcohol consumption (15), substance abuse (16), and unprotected sexual encounters (17), has demonstrated that immature mechanisms and neurotic defensive mechanisms serve as substantial risk factors for both the onset and continuation of these behaviors. Although there is substantial evidence indicating that defense mechanisms can predict risky behaviors (14-20), alternative psychological frameworks propose that the connection between these mechanisms and risky behaviors is influenced by a range of other personality factors, such as health beliefs and self-esteem (21-23). Self-esteem is defined as an individual's evaluation and judgment of their own worth and self-acceptance (24). The findings concerning the influence of self-esteem on risky behaviors are inconclusive (24, 25). Numerous studies have established a correlation between high self-esteem and a reduced likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors (26, 27). Conversely, certain research outcomes suggest that self-esteem may not serve as an effective deterrent against behaviors associated with legal violations, aggression, and delinquency; rather, it could potentially exacerbate the inclination towards such behaviors under particular circumstances (25, 28). The examination of the connections among self-esteem, defense mechanisms, and risky behavior is justified for various reasons. Notably, self-esteem is inherently linked to self-assessment and self-concept, which are significantly influenced by defense mechanisms (24). Second, individuals who depend on less mature defense mechanisms are prone to receiving negative feedback from their social environment, which can lead to a decline in their self-esteem (24). Consequently, these individuals might resort to maladaptive behaviors and risky actions as a means to reshape their identity and manage the negative self-perception that has emerged (29, 30). For reaching a more integrative theoretical framework, we applied a hybrid theoretical model with the ego psychology framework and cognitive behavioral factors as mediators (5). Furthermore, a burgeoning area in the etiology of risky behaviors involves finding trans-diagnostic factors, which refers to factors that can predict individual differences in engaging in risky behaviors or mental disorders, independent of specific theories (31, 32). It appears that self-esteem may function as a trans-diagnostic factor that could more accurately forecast risky behavior than the concept of defense mechanisms, which are predominantly shaped by psychoanalytic theories. Previous studies have indicated that self-esteem can serve as a trans-diagnostic element that connects different risk factors to risky behaviors (33, 34).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate how defense mechanisms and self-esteem could explain risk-taking behaviors among college students. The conceptual framework of the study is illustrated in Figure 1.

3. Methods

This research design was of a survey and correlational nature, with data collected cross-sectionally, utilizing self-report scales for data gathering. The target population consisted of undergraduate students aged 18 to 24 from Azad universities in Tehran during the academic year 2023 - 2024. To determine the sample size, the recommended formula for sample size calculation in structural equation modeling research was employed (35). Considering the potential for data attrition, the final sample size was adjusted to 410 participants. Sampling was conducted using a convenience method. The inclusion criteria included being enrolled in a university, an age range of 18 to 24 years, and the absence of any mental illness that could interfere with responding to the research questions.

3.1. Data Analysis

For data analysis, descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation, structural equation modeling, and path analysis were employed. The structural equation modeling and path analysis were conducted using the maximum likelihood method and the bootstrap method. Additionally, SPSS and AMOS16 software were utilized to perform the analyses.

3.2. The Defensive Styles Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed to assess defensive styles in individuals (36). This instrument consists of 40 items and evaluates three styles of defensive mechanisms: mature, neurotic, and immature. The Cronbach's alpha for the Persian version and English version of this scale were reported ranging from 0.75 to 0.85, and test-retest reliability coefficients were between 0.56 and 0.71 over an 18-day period for all three factors (37, 38).

3.3. The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

This scale is constructed for assessing global self-esteem (39). The convergent validity of this scale has been examined in relation to various dimensions of self-concept, including academic, social, emotional, familial, and physical aspects, revealing a correlation ranging from 0.28 to 0.50 (35). The reliability of the Persian form of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was assessed among university students and was found to be satisfactory (40).

3.4. Risk-Taking Behaviors Scale

This instrument comprises 38 closed-ended items, employing a five-point Likert scale to evaluate 38 distinct types of risk-taking behaviors (41). The assessment encompasses multiple dimensions, such as hazardous driving, aggression, smoking, substance use, alcohol intake, friendships with individuals of the opposite sex, interpersonal relationships, and sexual conduct. This scale is based on a native study regarding risky behaviors within an Iranian sample, and the findings possess cultural validity and reliability (41).

4. Results

4.1. Data Description

Participants were within the age range of 18 to 24 years, with 79 individuals (19.3%) aged 18 to 19, 182 individuals (44.4%) aged 20 to 21, and 149 individuals (36.3%) aged 22 to 24. The mean age and standard deviation of the participants were 21.13 years and 4.88 years, respectively. Among the participants, 250 (61%) were female and 160 (39%) were male. Additionally, 329 participants (80.2%) were single, while 81 participants (19.8%) were married. Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for defense mechanisms, self-esteem, and the tendency for risk-taking behaviors. The findings revealed that immature and neurotic defense mechanisms were positively correlated with risk-taking behaviors, whereas self-esteem demonstrated a significant negative correlation with these behaviors. Additionally, the mature defense mechanism did not show a significant correlation with risk-taking behaviors.

Abbreviation: M ± SD, mean ± standard deviation.

a P < 0.001.

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling and Direct Effect Analysis

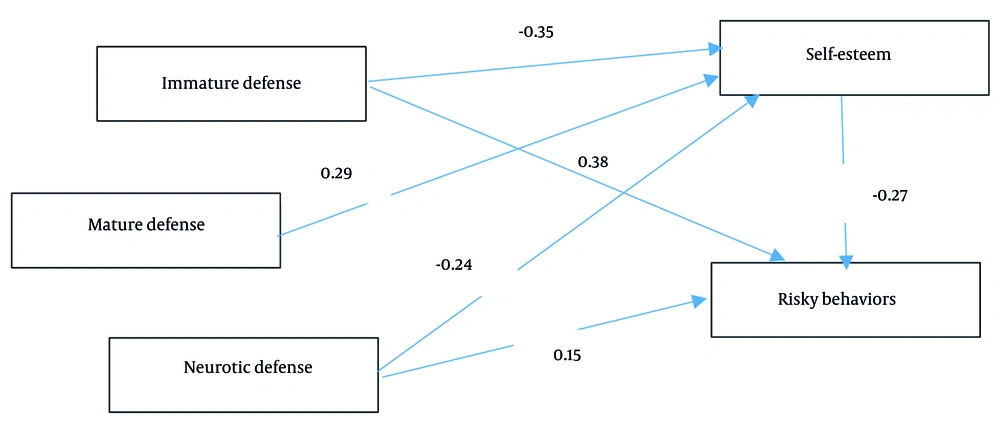

Structural equation modeling and path analysis were conducted using AMOS 26.0 software and maximum likelihood estimation (42). Table 2 presents the fit indices of the model after modification. In this study, the bootstrap estimation method was employed with a sample size of 2000 to estimate the standard error of indirect pathways. Table 3 displays the path coefficients among the variables. Furthermore, the schematic connection among the variables is depicted in Figure 2.

| Variables | Revised Model |

|---|---|

| Chisq/df | 2.08 |

| GFI | 0.995 |

| AGFI | 0.983 |

| CFI | 1 |

| RMSEA | 0.052 |

4.3. Mediation Analysis

The present research model comprises five observed variables, which leads to 15 known parameters. On the other hand, the number of unknown parameters is also 15, suggesting that we expect the degrees of freedom in the measurement model to be zero. This type of model, where the degrees of freedom are zero, is known as a saturated model (35). In a saturated model, the parameters are estimated while the goodness-of-fit indices are assumed to be perfect and are therefore not estimated. For this reason, in the initial analysis, the goodness-of-fit indices were not estimated due to the zero degrees of freedom, and the assessment of the parameters revealed that the relationship between the mature defense mechanisms and the inclination towards risky behaviors was not significant. Consequently, this pathway was eliminated, resulting in an increase in the model's degrees of freedom to one. This statistical strategy has been applied in previous studies (12, 35). Table 3 demonstrates that the direct and indirect path coefficients for neurotic defense mechanisms and immature defense mechanisms with risky behaviors were both positive. In contrast, the path coefficient linking self-esteem to risky behaviors (P = 0.001, β = -0.267) was negative. Conversely, the indirect path coefficient for mature defense mechanisms and risky behaviors (P = 0.001, β = -0.078) was negative.

| Path | B | SE | β | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | ||||

| Neurotic defense → self-esteem | -0.110 | 0.025 | -0.242 | 0.001 |

| Mature defense → self-esteem | 0.154 | 0.021 | 0.294 | 0.001 |

| Immature defense → self-esteem | -0.076 | 0.012 | -0.349 | 0.001 |

| Self-esteem → risky behaviors | -0.883 | 0.155 | -0.267 | 0.001 |

| Neurotic defense → risky behaviors | 0.219 | 0.077 | 0.146 | 0.001 |

| Immature defense → risky behaviors | 0.274 | 0.037 | 0.378 | 0.001 |

| Mature defense → risky behaviors | -0.006 | 0.011 | -0.024 | 0.573 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Neurotic defense → self-esteem → risky behaviors | 0.097 | 0.027 | 0.064 | 0.001 |

| Mature defense → self-esteem → risky behaviors | -0.136 | 0.031 | -0.078 | 0.001 |

| Immature defense → self-esteem → risky behaviors | 0.067 | 0.016 | 0.093 | 0.001 |

According to Figure 2, the relationships between neurotic defense mechanisms and risky behavior, as well as the connection between immature defense mechanisms and risky behavior, were significant. Additionally, self-esteem plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between neurotic and immature defense mechanisms and risky behavior. However, the relationship between mature defense mechanisms and risky behavior is not directly significant; this connection is established due to the mediating role of self-esteem. Furthermore, self-esteem serves as a complete mediator in the relationship between mature defense mechanisms and risky behaviors.

5. Discussion

The findings revealed that both immature and neurotic defense mechanisms exert a significant direct influence on the propensity for engaging in risky behaviors. This observation aligns with the outcomes of prior research (14-20). Several interpretations can be offered to elucidate the link between defense mechanisms and risky behaviors. Firstly, an increased frequency of maladaptive defense mechanisms implies that an individual may either lack adequate emotional stability or have experienced a decline in it for various reasons (6). From this angle, numerous risky behaviors can be perceived as inadequate strategies for emotional engagement (7). Secondly, as the maturity of a defense mechanism decreases, the individual's grasp on reality may become increasingly distorted or compromised (7), thereby heightening the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors as a result of this altered perception. Additionally, the results indicated that there is no significant direct relationship between mature defense mechanisms and risky behavior; however, this relationship becomes significant when self-esteem is considered as a mediating factor. This result indicates that during the period of young adulthood, independent of the maturity of defense mechanisms, individuals may exhibit a tendency towards risky behaviors that are shaped by their age, developmental context, and, significantly, by cultural and social restrictions (43). In other words, individuals in this age period have specific psychological and relational needs that likely do not correlate with the type of mature defense mechanisms they possess.

The findings further indicated that self-esteem exerts a significant negative direct influence on the likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors. This observation is consistent with the outcomes of earlier research (25, 27, 30). Self-esteem is a crucial element that may affect students' involvement in positive and constructive pursuits, such as education and employment, thereby significantly impacting the quality and extent of their participation in socially acceptable behaviors (44).

Also, findings of this study showed that neurotic, immature, and mature defense mechanisms had a significant indirect effect on the propensity for risk-taking behaviors, mediated by self-esteem. This finding supports the role of self-esteem as a candidate for a trans-diagnostic risk factor for predicting risk-taking behaviors (32). To elucidate this finding, it can be argued that when students employ dysfunctional defense mechanisms, their self-esteem is likely to diminish (17). This is due to the fact that neurotic and immature defense mechanisms during this age period are associated with strategies such as self-handicapping and procrastination (17, 45). The reduction in self-esteem, frequently associated with self-handicapping, can result in risk-taking behaviors, including alcohol use, as a strategy for managing challenging circumstances (15). In addition, this finding about the role of self-esteem further supports the positive and protective role of self-esteem in mental health and healthy behavior (26, 27, 33, 34). Also, the finding suggests that mature defense mechanisms are indirectly related to lower risky behavior via self-esteem. It seems the utilization of mature defense mechanisms leads to positive intrapersonal and interpersonal outcomes, which subsequently influences an individual's self-esteem. As a result, individuals are likely to make more balanced behavioral choices and be less motivated by the desire to compensate for low self-esteem or to attain self-worth by engaging in risky behaviors. This explanation aligns with perspectives that conceptualize risky behaviors as a form of negative identity formation (46).

The results have shown that neurotic defense mechanisms relate to risky behavior both directly and indirectly via self-esteem. The direct effect of defense mechanisms on risky behavior could explain why emotional dysregulation may result in impulsive actions, while the indirect influence may shed light on why some individuals consistently engage in risky behaviors.

The findings of the current study regarding the theoretical challenges surrounding self-esteem in relation to mental health suggest that authentic self-esteem, which is rooted in more mature defense mechanisms, is likely a protective factor in preventing mental health issues and risky behaviors. In contrast, self-esteem that stems from immature defense mechanisms is more prevalent among narcissistic and antisocial personalities (24, 28) and could lead to increased engagement in risky behaviors among these individuals.

This research encountered specific limitations that indicate potential directions for future inquiry. The study concentrated on a non-clinical demographic without a history of trauma, impulsivity, or psychiatric disorders; thus, analyzing this framework within clinical populations or among individuals with a history of risky behaviors could provide significant insights. Another limitation of the research is the lack of screening for participants regarding their trauma history and psychiatric disorders, which may potentially influence the results. It is ultimately recommended that, considering the sample's gender inequality, this model be analyzed separately for girls and boys, and that research be conducted on the various types of risky behaviors differentiated by gender among both groups. The ultimate limitation of this research pertained to certain cultural differences regarding the identification of risky behaviors (e.g., "friendships with the opposite sex"). Therefore, it is advisable to exercise greater caution when considering the generalizability of the findings of this study to cultures that are less restrictive.