1. Background

One of the most challenging life events is the death of a loved one (1). Grief is a universal response to loss, but the duration, intensity, and functional impact of grief vary significantly among individuals. While some individuals adapt to life without the deceased over time, others experience intense, prolonged grief symptoms that impair their functioning, necessitating therapeutic intervention and leading to the development of Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) (2-4). In the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5-TR), the diagnosis of PGD was placed in the category of trauma-related disorders (5). The PGD is diagnosed when, after 12 months, the person continues to experience prolonged symptoms such as persistent longing for the deceased, intense sadness, excessive thinking about the deceased, difficulty accepting the death, and difficulty recalling positive memories of the deceased, anger at the loss, and excessive avoidance of recalling the deceased’s death, which lead to a diagnosis of PGD (6). Various factors affect the prolongation of grief, including death caused by natural disasters; the prevalence of PGD due to natural disasters in the Iranian population is 38.81% (7). Grief is a universal experience; however, culture influences how individuals express and cope with loss (8, 9).

This study focused on university students because bereavement in this group can significantly disrupt academic performance, social functioning, and future career prospects, and the prevalence of PGD has been reported at 13.4% among students (10). University settings also offer practical advantages for recruitment and data collection, making them an accessible starting point for validating the Persian version of the GRS before extending research to other populations.

There are many models for the conceptualization of grief that consider grief as a stage, but further evidence-based models should consider cultural variations and individual differences (11). One model that conceptualizes grief responses well is the integrative-relational model. The integrative-relational model of Payas describes four dimensions that explain both adaptive grief response and PGD (12). The dimensions of Payas Puigarnau integrative-relational model are startling shock, avoidance-denial, continuing bonds-connection, and growth-transformation (13). This model focuses on types of grief responses occurring at different mourning times. In the stun-shock dimension, the bereaved person experiences rumination, confusion, dissociation, and hypervigilance (14). This dimension often occurs with traumatic deaths and predisposes the individual to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and PGD (15, 16). In the avoidance-denial dimension, the bereaved person uses a mechanism (17); if it continues, it becomes a stable defense (18), with symptoms including avoiding reminders of the deceased and engaging in activities to avoid the mourning environment. This avoidance can be automatic or intentional, such as intentionally avoiding locations associated with the deceased or experiencing automatic denial of the death (19). Symptoms of this dimension include avoiding reminders and intense feelings (14). Conversely, the bereaved person may seek reminders of the deceased through internalized memories and external reminders, maintaining the existence of the deceased person (14, 20). In the last dimension of Payas Puigarnau et al integrated relational model, growth-transformation, the bereaved person finds new meaning in life, which includes accepting the loss, determining new values and goals for the future, and rebuilding personal identity (14). The dimensions of the integrative-relational model, by considering both adaptive and maladaptive responses to grief and individual differences, address gaps in other conceptualizations of grief and indicate the forms of coping and their symptoms in individuals (21).

Although several grief scales, such as the Prolonged Grief Disorder Revised Scale (PG-13-R) and the Grief Experience Questionnaire (CEQ), have been developed (22, 23), few scales specifically address the grief response, which is an ongoing process following the initial grief experience, and few have been validated in Iran. Payas-Puigarnau designed a scale to examine grief responses, based on the integrative-relational model. As a result, this scale demonstrates the application of the theory, but further validation across diverse cultural contexts is necessary to determine its reliability, given that grief response varies across cultures. Also, despite investigations of grief in different populations, including adults and teenagers, limited research exists on the grief responses of students.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to examine the psychometric properties (factor structure, reliability, and validity) of the Grief Response Scale (GRS) among bereaved Iranian students.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This cross-sectional study was carried out among Iranian university students in 2024. Participants were recruited from university settings, and a total of 315 bereaved students completed the survey. The statistical population consisted of all bereaved students selected using an accessible sampling method of 315 people. To estimate the validity and reliability of the instrument, given that the present instrument has 32 questions, various guidelines have been proposed for determining sample size, ranging from 2 to 20 people per item in the existing literature (24). In this study, 10 participants were considered for each item, according to the suggestion of Tabachnik and Fidel (25). Therefore, the final sample was considered to be 320 people, and to reduce sample attrition, 332 samples were taken. After examining the samples, 17 subjects had attrition, and 315 samples were analyzed. The inclusion criteria were being a student, the ability to read and understand the questionnaire, and the death of a loved one, while the exclusion criterion was incomplete completion of the questionnaire. There were no restrictions regarding participants’ history of mental or physical illnesses, and the time elapsed since the loss of the loved one was not used as an inclusion or exclusion criterion. However, this variable was recorded for all participants for descriptive purposes. This approach was intended to evaluate the scale in a naturalistic and representative student population without clinical or temporal constraints.

The participants included 332 Iranian students. As answering all questions was mandatory, there were no cases of incomplete questionnaire completion; however, 17 questionnaires with patterned or extreme answers were removed, resulting in 315 samples analyzed. Among them, 56 participants (17.8%) were male and 259 (82.2%) were female. Ninety-seven people (30.8%) were married, and 218 (69.2%) were single. The age range was 18 to 57 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 30.41 and 10.83, respectively. Samples were collected from all levels of university education, including postgraduate studies. Data are shown in Table 1.

| Participants Characteristics | Variables (N = 315) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 259 (82.2) |

| Male | 56 (17.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 218 (69.2) |

| Married | 97 (30.8) |

| Age | 30.41 (10.83) |

| Education level | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 211(66.98) |

| Master’s degree | 90 (28.57) |

| PhD degree | 14 (4.44) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Grief Response Scale

The GRS, developed by Payas-Puigarnau et al. based on the integrative-relational model, includes four main dimensions and consists of 32 items. It was administered to 379 participants in Spain using a five-point Likert scale. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) identified six factors: Symptomatological distress, avoidance, loss orientation, positive changes, integration of loss, and social support (14). This tool measures natural, pathological, and positive grief responses. Since its psychometric properties have not been evaluated in Iran, this study aims to assess its reliability and validity in an Iranian sample. The questionnaire was translated into Persian and back-translated by English language experts and psychologists. The final version was pilot-tested on 32 participants.

3.2.2. Event Impact Scale-Revised

The Impact of Event Questionnaire (IES) was developed by Weiss and Berger in 2006 and includes 22 items across three subscales: Intrusion, hyperarousal, and avoidance. It is rated on a five-point Likert scale and has acceptable validity and reliability (26). In Iran, Sharif Nia et al. evaluated the validity and reliability of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) during the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population, reporting Cronbach’s alpha coefficients between 0.84 and 0.93 for the subscales (27). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.902.

3.2.3. Inventory of Complicated Grief

The Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) was developed by Prigerson et al. in 1995 (28). This instrument measures core symptoms of complicated grief, including longing for the deceased and complex emotional and behavioral responses. It consists of 19 items rated on a five-point Likert scale, with an internal consistency of 0.94 (28). In Iran, Yousefi et al. standardized the tool in 2022, reporting a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.94, indicating good validity and reliability (29). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.908.

3.2.4. Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (Subscales of Anxiety and Depression)

The Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90-R) of anxiety and depression, developed by Drugatis, includes 90 items covering a wide range of symptoms, with subscale reliabilities between 0.81 and 0.9 (30). In Iran, Nojomi and Gharayee standardized this tool among medical students, confirming its validity and reliability (31). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.925 for depression and 0.920 for anxiety.

3.2.5. Integration Scale of Stressful Life Experiences Short Form

The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale (ISLES) was developed by Holland et al. to assess individuals’ ability to integrate stressful or negative life events, including recent losses. The short form includes six items rated on a five-point Likert scale, while the long form contains 16 items (32). In Iran, Azadfar et al. standardized the scale, reporting a two-factor structure with acceptable validity and reliability (33). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.902.

3.2.6. Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form

The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) was developed by Cann et al. to assess post-traumatic growth. It includes 10 items rated on a six-point Likert scale. The long form was tested on 1,351 participants, while the short form was developed using data from 186 individuals; both versions demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability (34). In Iran, Amiri et al. standardized the inventory on a sample of 563 participants, confirming its validity and reliability for use in Iranian populations (35). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.857.

3.3. Procedure

After the cultural adaptation of the scale, a set of questionnaires was distributed to the sample, including the GRS, IES-R, ICG, Anxiety and SCL-90-R, Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Short Form (ISLES-SF), and Posttraumatic Growth Inventory Short Form (PTGI-SF). Participants were selected through convenience sampling from public universities across Iran, and the online questionnaire link was distributed via student communities and university communication platforms. The questionnaires were presented to participants online via a Google Forms link, where the purpose and ethical considerations were explained to obtain informed consent. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including standard deviation and mean, with SPSS version 24 and inferential statistics via the Pearson correlation test and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 24. The authors adhered to the ethical considerations of the research based on the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2008.

3.4. Data Analysis

Initially, descriptive statistics of each item of the GRS were calculated. To test the factorial structure of the instrument, EFA with the varimax rotation method was used. To determine the number of factors to be retained during EFA, the Kaiser-Guttman criterion was employed, retaining factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and items with factor loadings greater than 0.40 were retained. Additionally, CFA was conducted using the appropriate estimator. The main fit indices used were the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis Goodness-of-Fit Index (TLI), chi-square (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Normed Fit Index (NFI). Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega. Finally, convergent and divergent validity were evaluated through Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24 and Amos version 24.

4. Results

4.1. Item Analysis

All variables were first analyzed for normal distribution. None exceeded the standard value for skewness (≤ |2.0|) and kurtosis (≤ |4.0|) (36) (Table 2). In the present study, the reliability of the total items was examined using the corrected-item total correlation (CITC) and Cronbach’s alpha. The CITC of the items in the current sample was evaluated, and none of the items had a negative CITC (Table 2).

| Items | Mean ± SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Corrected Item-Total Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g1 | 1.87 ± 1.261 | 0.184 | -0.918 | 0.316 |

| g2 | 2.02 ± 1.237 | 0.019 | -0.871 | 0.351 |

| g3 | 1.5 ± 1.209 | 0.479 | -0.613 | 0.295 |

| g4 | 1.73 ± 1.24 | 0.238 | -0.82 | 0.351 |

| g5 | 1.74 ± 1.118 | 0.273 | -0.543 | 0.259 |

| g6 | 1.83 ± 1.41 | 0.123 | -1.235 | 0.189 |

| g7 | 1.31 ± 1.024 | 0.376 | -0.541 | 0.293 |

| g8 | 2.42 ± 1.27 | -0.228 | -1.093 | 0.129 |

| g9 | 2.44 ± 1.223 | -0.262 | -0.912 | 0.274 |

| g10 | 1.93 ± 1.266 | 0.081 | -1.058 | 0.073 |

| g11 | 1.69 ± 1.271 | 0.404 | -0.853 | 0.181 |

| g12 | 1.7 ± 1.287 | 0.364 | -0.907 | 0.301 |

| g13 | 1.97 ± 1.211 | 0.067 | -0.81 | 0.417 |

| g14 | 0.59 ± 1.019 | 1.742 | 2.135 | 0.244 |

| g15 | 2.3 ± 1.317 | -0.248 | -1.045 | 0.175 |

| g16 | 2.21 ± 1.238 | -0.206 | -0.937 | 0.136 |

| g17 | 2.5 ± 1.312 | -0.459 | -0.953 | 0.01 |

| g18 | 1.86 ± 1.353 | 0.103 | -1.221 | 0.379 |

| g19 | 1.97 ± 1.31 | 0.082 | -1.079 | 0.197 |

| g20 | 2.22 ± 1.317 | -0.189 | -1.058 | 0.289 |

| g21 | 1.45 ± 1.319 | 0.562 | -0.804 | 0.44 |

| g22 | 1.4 ± 1.202 | 0.623 | -0.471 | 0.354 |

| g23 | 1.33 ± 1.128 | 0.644 | -0.259 | 0.262 |

| g24 | 1.69 ± 1.125 | 0.223 | -0.626 | 0.183 |

4.2. Factorial Structure of the Grief Response Scale

For the EFA, extracted factors were determined by the Kaiser-Guttman criterion, retaining those whose eigenvalues exceeded 1 and which had factor loadings higher than 0.4. Six factors, similar to the original version, were extracted; the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.828, and Bartlett’s test significance was less than 0.001. These six factors explained 61.99% of the variance. The six constructs were named as symptomatological distress (5 items), positive changes (6 items), loss integration (3 items), loss orientation (3 items), avoidance orientation (4 items), and social support (3 items), based on the original questionnaire. As shown in Table 3, each factor demonstrated adequate factor loadings, with most items loading above 0.60. For example, symptomatological distress included items g1 to g5, with loadings ranging from 0.705 to 0.846. The internal consistency of the factors was generally acceptable: Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.595 (avoidance orientation) to 0.870 (symptomatological distress), while McDonald’s omega ranged from 0.604 to 0.873. The mean scores of each subscale indicated the relative prominence of each grief response type, with positive changes (M = 9.50, SD = 5.33) and symptomatological distress (M = 8.87, SD = 4.93) being the most highly endorsed factors in this sample (Table 3).

| Items | Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatological Distress | Positive Changes | Loss Integration | Loss Orientation | Avoidance Orientation | Social Support | |

| g4 | 0.846 | - | - | - | - | - |

| g3 | 0.805 | - | - | - | - | - |

| g2 | 0.797 | - | - | - | - | - |

| g1 | 0.768 | - | - | - | - | - |

| g5 | 0.705 | - | - | - | - | - |

| g21 | - | 0.849 | - | - | - | - |

| g18 | - | 0.782 | - | - | - | - |

| g22 | - | 0.695 | - | - | - | - |

| g19 | - | 0.654 | - | - | - | - |

| g14 | - | 0.614 | - | - | - | - |

| g20 | - | 0.415 | - | - | - | - |

| g15 | - | - | 0.748 | - | - | - |

| g17 | - | - | 0.632 | - | - | - |

| g16 | - | - | 0.585 | - | - | - |

| g11 | - | - | - | 0.754 | - | - |

| g13 | - | - | - | 0.744 | - | - |

| g12 | - | - | - | 0.463 | - | - |

| g10 | - | - | - | - | 0.734 | - |

| g9 | - | - | - | - | 0.708 | - |

| g8 | - | - | - | - | 0.654 | - |

| g6 | - | - | - | - | 0.441 | - |

| G24 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.812 |

| G23 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.775 |

| G7 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.726 |

| Mean ±SD | 8.87 ± 4.93 | 9.50 ± 5.33 | 7.01 ± 2.96 | 5.36 ± 2.87 | 8.62 ± 3.48 | 4.33 ± 2.66 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.870 | 0.798 | 0.648 | 0.634 | 0.595 | 0.738 |

| McDonald’s omega | 0.873 | 0.808 | 0.673 | 0.647 | 0.604 | 0.757 |

| Variance explained (Total = 61.99) | 15.747 | 13.238 | 8.329 | 7.976 | 7.576 | 9.128 |

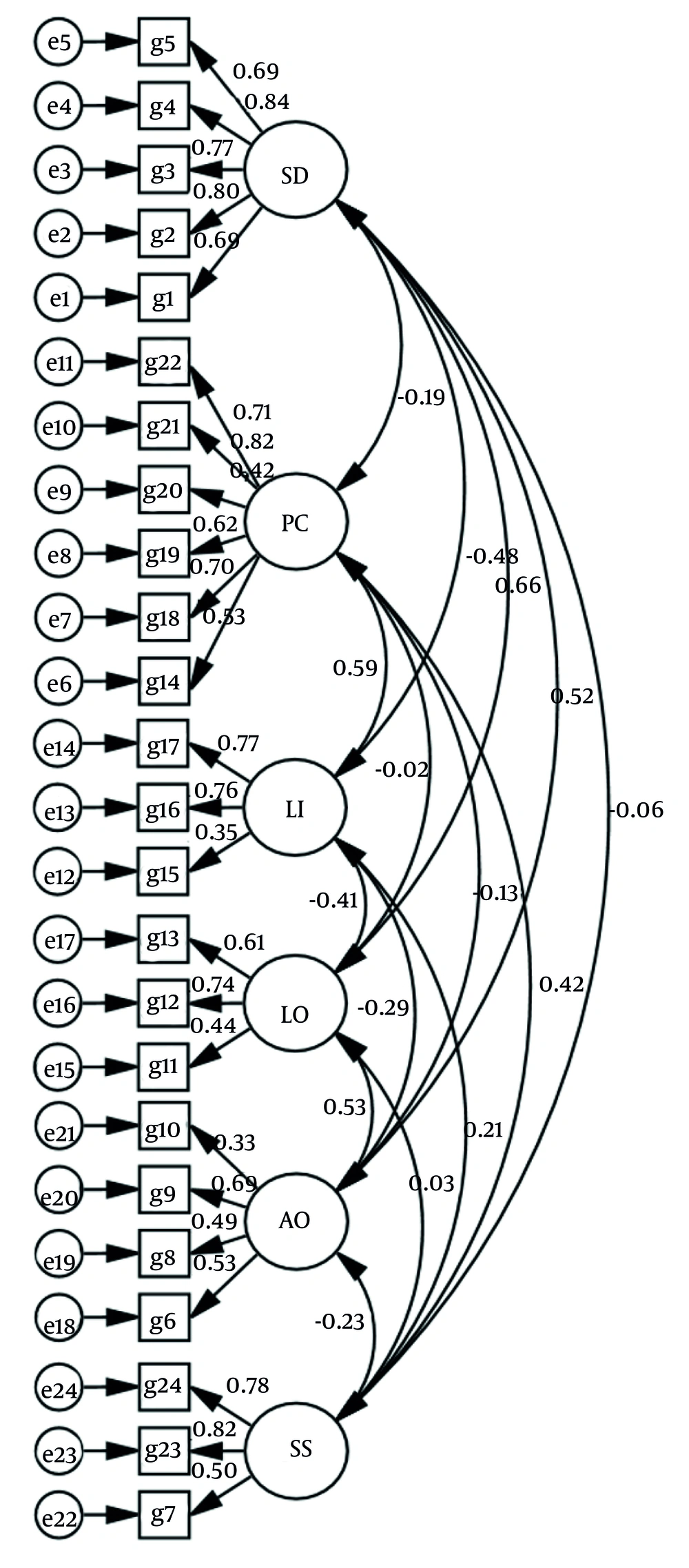

Secondly, after the CFA (Table 4), the fit indices revealed that the χ2/df Index, RMSEA, and SRMR were acceptable, but the CFI, NFI, and TLI indices were slightly less than acceptable (Table 4).

| Fit Index | χ2/df | RMSEA | SRMR | NFI | CFI | TLI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed value | 2.655 | 0.073 | 0.084 | 0.880 | 0.848 | 0.823 |

| Level of acceptance | < 3 | < 0.08 | < 0.08 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 | > 0.90 |

Abbreviations: χ2, chi-square test; df, degrees of freedom; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; NFI, Normed Fit Index; GFI, Goodness of fit Index.

Figure 1 shows the CFA of the GRS. In this diagram, the six main factors of the model are shown along with their items. The paths between the items and the factors represent the factor loading coefficients, which indicate the influence of each item on the factor. The standardized path coefficients indicate the strength of the relationship between the variables, and the two-way arrows indicate the correlation between the factors. The value of RMSEA is at an acceptable level, indicating a relative fit of the model with the empirical data. Overall, this figure provides a picture of how the scale factors are organized and related, and confirms the six-factor structure for this instrument. As shown in the model fit indices, the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df = 2.655) falls within the acceptable range (< 3), and the RMSEA value is 0.073, indicating a reasonable error of approximation. The SRMR value of 0.084 is marginally acceptable. However, the CFI (0.848), NFI (0.880), and TLI (0.823) are slightly below the conventional cutoff of 0.90, suggesting a moderate but not perfect fit. Overall, the CFA supports the six-factor structure of the GRS in the Persian version, consistent with the original model.

4.3. Reliability

As observed in Table 3, to evaluate the reliability of the Persian version of the GRS, its internal consistency was evaluated by calculating Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega for each construct. Three of the subscales had adequate reliability values (≥ 0.70), while the subscales of loss integration, loss orientation, and avoidance orientation were slightly lower (include the value of them).

4.4. Validity

To assess the convergent validity of the GRS, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between its subscales and theoretically related constructs measured by established instruments. Convergent validity refers to the degree to which two measures that should be related are in fact related. The selected instruments — IES-R, ICG, SCL-90-R (anxiety and depression), ISLES-SF, and PTGI-SF — assess psychological constructs such as trauma, complicated grief, emotional distress, meaning-making, and posttraumatic growth, which are conceptually relevant to grief responses. The IES-R, ICG, SCL-90-R anxiety and depression scale, ISLES-SF, and PTGI-SF were used to check the convergent validity of the GRS Questionnaire (Table 5).

| Variables | IEST | ICGT | SCL-Depression | SCL-Anxiety | PTGT | ISLEST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatological distress | 0.607 a | 0.586 a | 0.706 a | 0.746 a | -0.267 a | 0.536 a |

| Positive changes | -0.051 | -0.120 b | -0.231 a | -0.212 a | 0.660 a | -0.280 a |

| Loss integration | -0.316 a | -0.464 a | -0.396 a | -0.341 a | 0.308 a | -0.577 a |

| Loss orientation | 0.519 a | 0.648 a | 0.519 a | 0.448 a | 0.023 | 0.469 a |

| Avoidance orientation | 0.495 a | 0.431 a | 0.316 a | 0.306 a | -0.095 | 0.353 a |

| Social support | -0.013 | -0.058 | -0.03 | 0.022 | 0.216 a | -0.079 |

a P < 0.01 (statistically significant).

b A P-value < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

The present data show a Pearson correlation between the GRS and the convergent instruments such as IES-R, ICG, SCL depression, SCL anxiety, and ISLES-SF, providing evidence for convergent validity. For example, symptomatological distress showed a strong positive correlation with the constructs of SCL depression and SCL anxiety and a moderate correlation with IES-R and ICG. These findings indicate that the GRS Questionnaire is effective in aligning with instruments measuring similar constructs, thereby supporting its convergent validity. In Table 5, the subscale "Symptomatological Distress" shows significant positive correlations with IES-R (r = 0.607), ICG (r = 0.586), SCL-depression (r = 0.706), and SCL-Anxiety (r = 0.746). The subscale "Positive Changes" shows a significant positive correlation with PTGI-SF (r = 0.660) and negative correlations with the other instruments. Other subscales, including "Loss Integration", "Loss Orientation", "Avoidance Orientation", and "Social Support", display varying patterns of correlation with the different measures, as presented in the table.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the GRS based on the integrative-relational model in bereaved students. Specifically, this study examined convergent and divergent validity, EFA, fit, and reliability indices. The six-dimensional structure of this scale derives from the integrative-relational theoretical model of grief, which emphasizes the grief response process. The findings indicated that the GRS Scale is a valid scale for evaluating various grief response types based on the integrative-relational model (21) in bereaved students. With a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.705, the GRS Scale demonstrated sufficient reliability for use among bereaved student populations (37).

The assumption of data normality was confirmed using skewness and kurtosis values, which are important for parametric analyses such as factor analysis. To evaluate the validity of the GRS Scale, CFA was conducted. The model fit indices indicated an excellent chi-square to χ2/df; RMSEA and SRMR were acceptable, but the CFI, NFI, and TLI fell slightly below the commonly recommended threshold of 0.90, indicating minor limitations in model fit. Supporting studies from non-Western contexts corroborate the hypothesis that marginal CFA fit indices may arise from cultural differences in grief expression and item interpretation rather than inherent scale deficiencies. For example, in developing the Hospice Foundation of Taiwan Bereavement Assessment Scale (HFT-BAS) among Taiwanese bereaved adults, CFA yielded borderline fits (e.g., CFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.87, NNFI = 0.87), attributed to Eastern cultural emphases on familial grief and collective attachments contrasting Western individualism, necessitating integration of local philosophies for improved model fit (38). Similarly, a cultural adaptation of a grief measure for American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations revealed initial poor CFA fits (CFI = 0.83, TLI = 0.82), linked to normative positive connections with the deceased (e.g., visions) in indigenous cultures, which differ from Western views of complicated grief, requiring item removal to achieve acceptable fits (39). These results indicate the model has a reasonable fit with the data and a strong fit overall (40).

The internal consistency of the overall scale was acceptable; however, some subscales, such as loss orientation and avoidance orientation, demonstrated relatively lower Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. This may be attributed to the limited number of items in these subscales, which can affect the stability of reliability estimates (14). Additionally, cultural variations in grief expression or conceptual differences in how certain aspects of grief are perceived in the Iranian context may have influenced the consistency of responses within these dimensions (41). Further refinement of these subscales or the inclusion of additional culturally relevant items may improve internal consistency in future studies.

Six factors were extracted in the EFA, including symptomatological distress, positive changes, loss integration, loss orientation, avoidance orientation, and social support. According to the original article, the results revealed that they explain 61.99% of the variance and the multidimensional nature of grief responses, which is almost in line with the number reported in the original article (62%). The extraction of six factors emphasizes the multifaceted nature of grief responses, highlighting that each factor indicates a distinct aspect of grief processing across individuals. This, in turn, shows that each factor represents a different process and response to grief in different people. As a result, the grief response is not a linear experience but a complex interaction of emotions and various coping strategies, consistent with findings from similar studies that categorize grief into dimensions such as symptomatic distress and social support (42, 43).

When bereaved students react with symptomatological distress, they experience severe anxiety and depression that can affect their academic performance (44, 45). The physical response to grief is one of the symptomatic distresses that may disturb the daily life of bereaved students (46). Some bereaved students experience positive changes, including personal growth; they report greater empathy and flexibility after experiencing grief. This dimension demonstrates that grief can enhance coping skills (47, 48). Students who integrate their grief into their life experience and express the loss integration dimension have a healthier grief response, resulting in better emotion regulation and fewer symptoms of complicated grief (49). Bereaved students who have a loss orientation maintain their relationship with the deceased. The continuous bonding experience is useful for the survivor’s comfort, but if its intensity increases, it leads to prolonged grief symptoms (50). In the avoidance orientation, the bereaved students distance themselves from reminders of the deceased, which in the long term strengthens the symptoms of prolonged grief (51). Finally, in the social support dimension, the bereaved students feel isolated due to the reduction in support from those around them (52).

The hypothesis of internal consistency for symptomatological distress and positive changes was high in both studies, indicating the reliability of the scale in different cultures. However, the loss orientation subscale in both studies had lower reliability than other subscales, which may be due to the limited number of questions, and the loss orientation subscale can be reviewed and modified.

The hypothesized six-factor structure of the GRS, based on the integrative-relational model, was confirmed, and the results of both the present study and the preliminary study revealed the multifacetedness of grief responses with high factor loadings and strong internal consistency. Consequently, this scale demonstrates the types of grief responses across different cultures.

While most GRS subscales indicate high reliability (α > 0.70), Cronbach’s alpha values were below 0.70 for the loss orientation, loss integration, and avoidance orientation subscales. This finding is consistent with the original study regarding lower loss orientation, but in the present study, the dimension of social support was higher than in the original study. This indicates that, in Iranian culture, the social support dimension is stronger in response to grief, reflecting a cultural difference in the way people bond with the deceased. These findings emphasize the importance of cultural differences in Iranian students; therefore, the GRS may need adaptation in different cultural contexts to more accurately capture other dimensions of grief response.

Ethnographic research by Karimitar (53) supports the view that Iranian mourning practices are deeply influenced by spiritual traditions, gendered expressions, and collective ceremonies that strengthen social support networks. These rituals, firmly rooted in religious and ethnic customs, shift the focus from individual grief to communal mourning, providing emotional relief and reinforcing familial and spiritual bonds (53). Iranian grief responses, shaped by Shiite Islamic traditions, emphasize elaborate religious rituals and community support that transform individual sorrow into communal resilience (54). This differs from Sunni-majority Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, where tomb decorations and women’s grave visits are often prohibited, leading to more restrained mourning practices (55, 56). Compared to Western societies, where grief is often individualized, medically pathologized, and associated with higher death anxiety and institutional care (e.g., hospital deaths and secular coping), Iranian mourning integrates spiritual acceptance of death as a divine transition, reducing anxiety through afterlife beliefs and fostering emotional relief via strong familial bonds, as documented in ethnographic studies of war-exposed populations (54).

In this way, the unique cultural context of Iran, as a non-Western society, shapes grief responses through these collective and ritualistic practices. Consequently, during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, disruption of these communal rituals has led to increased unresolved grief and highlighted the urgent need for psychosocial interventions (55, 57).

The hypothesis regarding convergent and divergent validity was confirmed, with results showing that symptomatological distress and avoidance orientation have strong positive correlations with measures of post-traumatic stress, complex grief, and anxiety and depression subscales, consistent with theoretical expectations. Conversely, positive changes and loss integration are positively correlated with post-traumatic growth and integration of stressful life experiences, supporting the validity of the GRS Scale.

The negative correlation between symptomatological distress and positive changes suggests that unresolved grief hinders post-traumatic growth. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have shown that distress is a predictor of complicated grief.

The clinical implications of the present study are as follows. The findings presented the GRS as a robust, multidimensional scale that encompasses a wide range of grief responses among Iranian students. The generally acceptable psychometric properties of this scale support its use in identifying types of grief responses and individuals at risk of PGD, thus aiding in prevention. According to the multidimensional grief theory (58), identifying different grief responses helps grief experts tailor approaches to individual needs. This questionnaire is also useful for crisis intervention experts working in the grief field. The validated questionnaire can be a valuable tool for mental health screening, particularly in university counseling centers. Finally, the GRS provides a practical tool for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions based on the integrative-relational model in diverse populations.

Despite the acceptable psychometric properties of the GRS, several limitations should be noted. First, the instrument was administered exclusively to a student population. These characteristics, including the predominance of female participants and the relatively higher mean age, should be considered when interpreting the findings, as they may limit the generalizability of results to broader bereaved populations. Second, data were collected via self-report questionnaires, which may introduce response bias, as individuals differ in their willingness and accuracy when disclosing grief responses. Third, the study experienced a modest attrition rate, with 17 out of 332 participants dropping out, primarily due to non-engaged response patterns such as identical or systematically extreme answers. Although relatively small, this dropout may have slightly impacted the representativeness of the final sample and should be considered when interpreting the results. Fourth, the predominance of female participants (82.2%) may have influenced the pattern of responses, as prior research suggests women tend to report higher levels of emotional expression and social support seeking in grief contexts. This gender imbalance could limit generalizability to male students and warrants targeted recruitment strategies in future studies. Finally, neither mental health history nor bereavement duration was used as an exclusion criterion. This decision was made intentionally to preserve the naturalistic and representative nature of the student sample. Nonetheless, these factors could have influenced grief response patterns and should be controlled for in future studies to enhance validity.

Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews or behavioral observations, in addition to self-report questionnaires, to minimize the possible effect of response bias in the measurement of grief responses and increase data reliability. The majority of female students (82.2%) may restrict the generalizability of the results to male students, and the slightly higher mean age indicates the presence of both traditional and non-traditional students; their differentiation should be considered when interpreting the findings. Although the current study is the first norming study of the GRS in a different culture, its strength lies in investigating grief in the student body. Given its novelty, high reliability, and brevity, this study is an appropriate choice for assessing grief responses. In future research, it is recommended that the GRS be investigated in other populations, particularly those with PGD, and via longitudinal designs to trace the course of grief responses over time and investigate the design of culturally appropriate interventions. Additionally, comparing the scale in other non-Western groups can provide greater insights into both its cross-cultural validity and the cultural construction of grief.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study confirmed the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the GRS among bereaved Iranian students, supporting its six-factor structure based on the integrative-relational model. The GRS appears culturally relevant and useful for mental health professionals, including in screening programs to identify students at risk for PGD and enable timely interventions. Future studies should assess its applicability in other populations and settings.