1. Background

Schizophrenia is one of the most severe, chronic, and debilitating mental disorders, characterized by impaired reality testing, hallucinations, or delusions, and affects individuals’ perceptions, thoughts, moods, emotions, and behavior (1). This disease accounts for approximately one percent of the population and has a profoundly destructive and debilitating effect on the affected individual and their family (2). Schizophrenia often occurs at a young age, leading to a decline in functioning and personality disintegration, severely impacting and endangering personal life, social relationships, work, and education (3, 4). Suicide is the leading cause of death in individuals with schizophrenia, and compared to the general population, these patients have a 10 - 25% life expectancy (5). Given the complexity and diversity of this disease and the scarcity of complete evidence regarding its causes, a comprehensive and definitive treatment has not yet been discovered. Therefore, researchers continue to seek new treatments to reduce symptoms and improve life expectancy in these patients (6).

Recent studies have shown the positive and possible effects of physical activity on reducing positive and negative symptoms and suicidal thoughts in patients with schizophrenia, though uncertainty remains about the effect of aerobic exercise on the severity and intensity of symptoms and suicide risk in these patients (7).

2. Objectives

Considering the potential effects of exercise on reducing suicidal thoughts and symptoms, and the limited attention this area has received, we conducted the present study to investigate the effect of aerobic exercise on the severity of suicidal thoughts and symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.

3. Methods

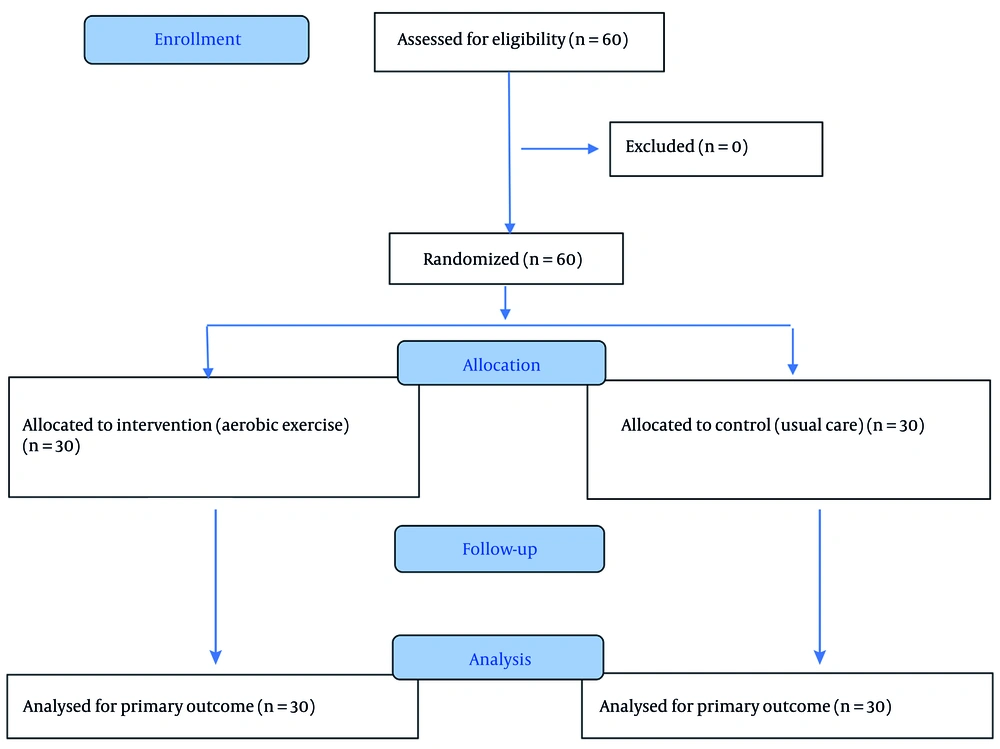

In this randomized controlled clinical trial, 60 patients with schizophrenia were selected through convenience sampling and then randomly assigned into two groups: Intervention and control (30 subjects in each group). All participants were hospitalized in psychiatric wards at Imam Reza Hospital in Birjand and Mahdis Chronic Care Center in Birjand in 2023. Inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 - 65 who met the criteria for schizophrenia based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), with at least one hospitalization period and sufficient physical health to participate in the exercise program. The exclusion criterion was absenteeism for more than four sessions.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was used to measure positive and negative symptoms, and the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation was used to assess suicidal thoughts. Aerobic exercises were performed by patients with schizophrenia under the supervision of a trained physical education instructor. The aerobic exercise protocol included a 5-minute warm-up (jogging, combined arm-leg movements, and stretching), 20 minutes of main exercise comprising 10 minutes of jogging at an intensity of 60 - 80% of maximum heart rate and 10 minutes of invisible jumping rope in 5 sets (30 repetitions per set), with 1 minute of rest (jogging on the spot and deep breathing) after each set, and finally 5 minutes of cool-down to return to the initial state.

To ensure adherence to the exercise protocol, attendance at each session was recorded by the supervising instructor. The number of completed sessions was tracked for each participant, and any missed or partially completed sessions were documented. On average, participants attended 93% of the planned sessions, indicating high adherence to the intervention. Additionally, participants’ heart rates were monitored using a portable heart rate monitor to ensure that the prescribed exercise intensity (60 - 80% of maximum heart rate) was achieved during the sessions. These measures ensured fidelity to the exercise protocol and allowed accurate assessment of the intervention’s effect.

Participants in the control group continued their usual daily activities in the hospital setting without engaging in any structured exercise or stretching program. No sham or active control intervention was provided to the control group. This was clarified to minimize potential confounding effects due to additional physical activity.

The assessment of the PANSS and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation scores was performed before the intervention and at weeks 2, 4, and 8 after the end of the intervention. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 24 (P < 0.05).

The standard PANSS was used to measure the severity of schizophrenia symptoms. This tool comprises 30 items, each rated based on symptom severity from 1 (minimum) to 7 (very severe). The minimum total score is 30. The PANSS has good inter-rater reliability, adequate construct validity, and high internal reliability. This tool is one of the most widely used symptom rating scales in schizophrenia research (7).

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation was used to examine the level of suicidal thoughts in the participants. The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation is a 19-item self-assessment tool. Each item has three options and is scored using the Likert method, with scores for each item ranging from 0 - 2. The total score ranges from 0 - 38. A score of 0 - 5 indicates the presence of suicidal thoughts, 6 - 19 indicates readiness for suicide, and 20 - 38 indicates the intention to commit suicide. The validity and reliability of the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation are 0.76 and 0.95, respectively (5). The flow of participants through each stage of the trial is shown in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

4. Results

The mean age of the intervention group was 34.66 ± 11.25 years, and in the control group, it was 40.40 ± 10.47 years. Analysis of the findings indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the severity of schizophrenia symptoms between the groups before the intervention. However, 8 weeks after the intervention, the average PANSS score in the intervention group was 38.53 ± 9.92, and in the control group, it was 112.13 ± 17.87, indicating a statistically significant difference between the groups (Table 1).

| Groups | Time | Repeated Measure ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Intervention | Week 2 | Week 4 | Week 8 | ||

| Cases | 111.00 ± 21.85 | 88.73 ± 21.45 | 68.93 ± 13.12 | 38.52 ± 9.92 | P > 0.001, F = 170.68 |

| Controls | 112.86 ± 17.90 | 110.73 ± 17.85 | 111.00 ± 19.41 | 112.13 ± 17.87 | P = 0.52, F = 0.76 |

| Independent t-test result | P > 0.80, t = -0.25 | P > 0.005, t = -3.05 | P > 0.001, t = -6.95 | P > 0.001, t = -13.94 | - |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

In addition, the results of the paired comparisons showed that in the intervention group, all time-point comparisons were statistically significant (P < 0.001), indicating a consistent and meaningful reduction in symptom severity across all phases of follow-up. In contrast, in the control group, none of the paired comparisons reached statistical significance (P > 0.05), suggesting that symptom severity remained unchanged throughout the study period. Analysis of the findings indicated a statistically significant difference in the mean scores of suicidal ideation before and at 2, 4, and 8 weeks after the intervention (Table 2).

| Group | Time | Friedman Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Intervention | Week 2 | Week 4 | Week 8 | ||

| Cases | 7.60 ± 11.75 | 5.93 ± 8.89 | 3.26 ± 5.24 | 0.73 ± 1.83 | P > 0.001, df = 3.00 |

| Controls | 10.33 ± 8.87 | 9.80 ± 8.84 | 9.60 ± 8.74 | 9.40 ± 8.75 | P = 0.48, df = 3.00 |

| Mann-Whitney-U test result | P > 0.06, Z = -1.89 | P > 0.04, Z = -1.97 | P > 0.006, Z = -2.73 | P > 0.001, Z = -4.41 | - |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

The post-hoc pairwise comparisons based on the Friedman test showed that all within-group comparisons in the intervention group were statistically significant (P < 0.05), reflecting a continuous and meaningful decline in suicidal ideation across all follow-up intervals. In contrast, in the control group, only the comparison between baseline and week 8 demonstrated a statistically significant difference (P = 0.046), while all other pairwise comparisons were non-significant (P > 0.05).

Analysis of the findings also indicated a significant difference in mean changes in schizophrenia symptom severity scores at 2, 4, and 8 weeks after the intervention, while the mean changes in suicidal ideation scores did not show a statistically significant difference at weeks 2, 4, and 8.

5. Discussion

The data obtained from this study indicated a significant effect of aerobic exercise on reducing schizophrenia symptoms and suicidal ideation. It is important to note that the reduction observed in schizophrenia symptom severity was not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful. The magnitude of change clearly exceeded what is typically considered the minimal clinically important improvement in PANSS outcomes. Such a decrease reflects a substantial therapeutic impact that goes beyond statistical trends and suggests real-world benefits for patients, including more effective symptom control and potentially improved daily functioning. These results indicate that aerobic exercise likely produced a large treatment effect, emphasizing its value as a complementary intervention alongside standard pharmacological care.

Regarding suicidal ideation, although the intervention produced a clear and statistically significant decline during follow-up, these findings should be interpreted with caution. The two groups did not start at an identical baseline, and this initial imbalance may have contributed to part of the observed change through regression to the mean rather than the intervention alone. While the trend in the intervention group remains clinically reassuring, baseline differences should be acknowledged as a methodological limitation when interpreting the true magnitude of the treatment effect.

A meta-analysis by Guo et al. suggested that combining conventional drug treatments with aerobic exercise interventions is more effective than drug treatment alone in reducing schizophrenia symptoms (8). A study by Swora et al. shows that physical activity interventions are associated with beneficial effects on positive and negative symptoms and with better cognitive performance (9). Holley et al. recommends at least one 30-minute exercise session to maintain physical fitness as a healthy lifestyle (10). The results obtained from these studies are consistent with the current study. Aerobic exercise appears to reduce symptom severity by affecting brain chemical mediators that play a major role in the symptoms of schizophrenia, generally leading to better treatment outcomes.

Vancomfort et al. conducted a meta-analysis to examine the effects of aerobic exercise in patients with schizophrenia and concluded that exercise affected cognitive function and negative symptoms in these patients (11). In addition, in 2021, a study by Papiol et al. showed that the most beneficial effects of physical activity were seen on negative symptoms, especially cognitive dysfunction, and to a lesser extent on positive symptoms (12), which may be because Papiol et al.'s study, unlike the present study, examined the preventive effects of physical activity in these patients (12). Other studies show that exercise regulates neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin. Other neurochemicals that may be released during physical activity include opioids and endocannabinoids, which cause feelings of euphoria and happiness, and have anti-anxiety and sedative effects (13). The regulatory effects of exercise on brain chemical mediators can be cited as a possible reason for the reduction and improvement of schizophrenia symptoms.

A study by Vancampfort et al. indicated that higher levels of physical activity are associated with lower suicide rates (11). A study by Seddighi et al. also showed that exercise is effective as an adjunct treatment for people experiencing suicidal thoughts (14). In their study, Brailovskaia et al. showed in 2021 that physical activity, combined with positive mental health, can reduce the risk of suicide-related outcomes (15). In this regard, another study showed that active participation in sports is strongly associated with negative automatic thoughts, suicidal thoughts, and hopelessness (16). A study by Grasdalsmoen et al. suggested that there is a link between inactivity and poor mental health, self-harm, and suicide attempts (17). Legrand et al., in their study on the effect of physical activity on women hospitalized in a psychiatric ward after a suicide crisis, showed that two daily sessions of brisk/slow walking and running, in addition to routine care for these patients, improved hopelessness and suicide risk in these patients (18). The findings of the above studies are all consistent with the findings of the recent study. It is likely that the positive changes and reduction in suicidal thoughts in patients with schizophrenia, like the effects of exercise on the symptoms of schizophrenia, are related to the changes in brain chemical mediators caused by exercise. In a study conducted by Fabiano et al. in 2024, no significant relationship was found between suicidal thoughts or suicide deaths and physical activity (19). This inconsistency may be because the article by Fabiano et al. was related to patients with acute psychotic disorders, and therefore, the effects of exercise on chronic disorders examined in our study may differ from its effect on acute mental illnesses (19).

5.1. Conclusions

In general, and by analyzing the findings of this study, it can be concluded that physical activity and aerobic exercise have a significant effect on the severity of schizophrenia symptoms and can be considered as a complementary treatment in managing this disease. Using exercise to reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia can greatly help reduce treatment costs, decrease the length of hospitalization, improve treatment outcomes, and facilitate the patient’s return to family and society more quickly.

In addition, it can be concluded that aerobic exercise can help reduce suicidal thoughts and the suicide rate in this group of mental disorders, as well as possibly in depressed patients who struggle with suicidal thoughts, thereby reducing the mortality rate of these patients due to suicide.

5.2. Limitations

The study sample consisted solely of hospitalized patients, who may have more severe symptoms or different treatment resistance compared to outpatient cohorts. Consequently, findings may not be fully generalizable to all patients with schizophrenia. Additionally, while neurobiological pathways such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or endocannabinoid activity may mediate the effects of exercise, these biomarkers were not measured, which limits mechanistic interpretations. Medication stability was ensured prior to intervention, but variations in treatment regimens could still influence outcomes.