1. Background

Diabetes mellitus is characterized by high blood glucose due to deficiencies in insulin production or function, arising from various causes and leading to disturbances in protein and fat metabolism (1). Type 1 diabetes (T1D) has a global incidence of 15 per 100,000 and a prevalence of 9.5% (1), and in Iran, it affects 14 per 100,000 individuals (2). Among children and adolescents, this rate is 11.07% (3). Early onset increases the risk of early complications. Poor adherence to oral medication regimens impedes glucose control (4).

This disease severely affects mental health. The burden of chronic illness may significantly impact self-management ability and motivation, engagement in physical activity, and social interactions (4). Moreover, it can lead to psychological distress (5), depressive symptoms (6), and anxiety (7). Emotion regulation, strongly linked to treatment adherence and glucose control (8), involves modifying emotional experiences for social acceptance and affects psychological and physiological responses to external and internal demands (9). Difficulties include non-acceptance of emotions, behavior control issues during distress, and the inability to use emotions functionally (10).

Given the link between emotion regulation and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity, including cortisol regulation, adolescents with better emotion regulation may achieve superior glucose control during stress (8). Thus, intervention programs are essential. Traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is widely used to manage distress and promote self-management in chronic conditions (11). However, while CBT is the most extensively studied intervention, evidence suggests it may not be the most effective approach for adolescents (12). Many studies are limited by small sample sizes, lack of randomization, and short follow-up periods (4, 13). Furthermore, CBT protocols are often highly structured and primarily focus on modifying thoughts, which may not fully address adolescents’ emotional and motivational needs, particularly in the context of chronic illness.

In contrast, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) fosters psychological flexibility and value-based engagement, making it potentially more adaptive — even in group formats (4, 13, 14). The ACT has emerged as a promising alternative for adolescents with chronic illnesses such as T1D, as it emphasizes psychological flexibility over symptom elimination (12, 15, 16).

Developed by Steven Hayes in the 1990s (4), ACT is a newer form of CBT that evolved from empirical research on the effects of language on behavior, partly based on Relational Frame Theory. The ACT recognizes many forms of distress as natural consequences of being human. Unlike traditional therapies, its explicit goal is not necessarily to reduce distress; rather, symptom reduction may occur as a byproduct of increased psychological flexibility and engagement in meaningful activities (14). The ACT teaches patients to manage controllable aspects of their illness while accepting its uncontrollable parts, encouraging mindful presence with illness-related thoughts (17). Openness and acceptance of thoughts and emotions, even painful ones, can make them more tolerable and less threatening (15).

The ACT is particularly relevant for adolescents with T1D, as it emphasizes psychological flexibility — enabling individuals to accept illness-related distress while engaging in value-driven behaviors (15). Evidence indicates that ACT enhances emotion regulation and self-care in the context of chronic illness (14). In a clinical trial involving Iranian children with T1D, ACT was found to reduce stress and improve health-related self-efficacy, further supporting its applicability in this population (16).

Evidence suggests that ACT leads to improvements in symptom measurement, quality-of-life outcomes, and psychological flexibility, as reported by clinicians, parents, and self-reports (12). Moreover, its effectiveness has been demonstrated across various populations in areas such as reducing psychological distress (18, 19), enhancing emotion regulation (20, 21), and reducing anxiety (22, 23).

Given the prevalence of T1D, its psychological impact on adolescents, and their potential frustration with treatment, psychological interventions are essential (16). Despite a growing body of evidence supporting ACT across diverse populations, randomized controlled trials specifically assessing its efficacy for adolescents with T1D remain scarce. This population faces distinct emotional and self-regulatory challenges arising from their chronic condition. Most available studies lack methodological rigor — such as randomization and follow-up — or do not target this specific demographic (12, 20). Although ACT has shown promising results in enhancing emotion regulation and reducing anxiety among general adolescent samples, its application in diabetes-specific contexts is still underexplored.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to address this gap by evaluating the effectiveness of ACT in improving emotional functioning and reducing anxiety in adolescents with T1D using a controlled, methodologically robust design.

3. Methods

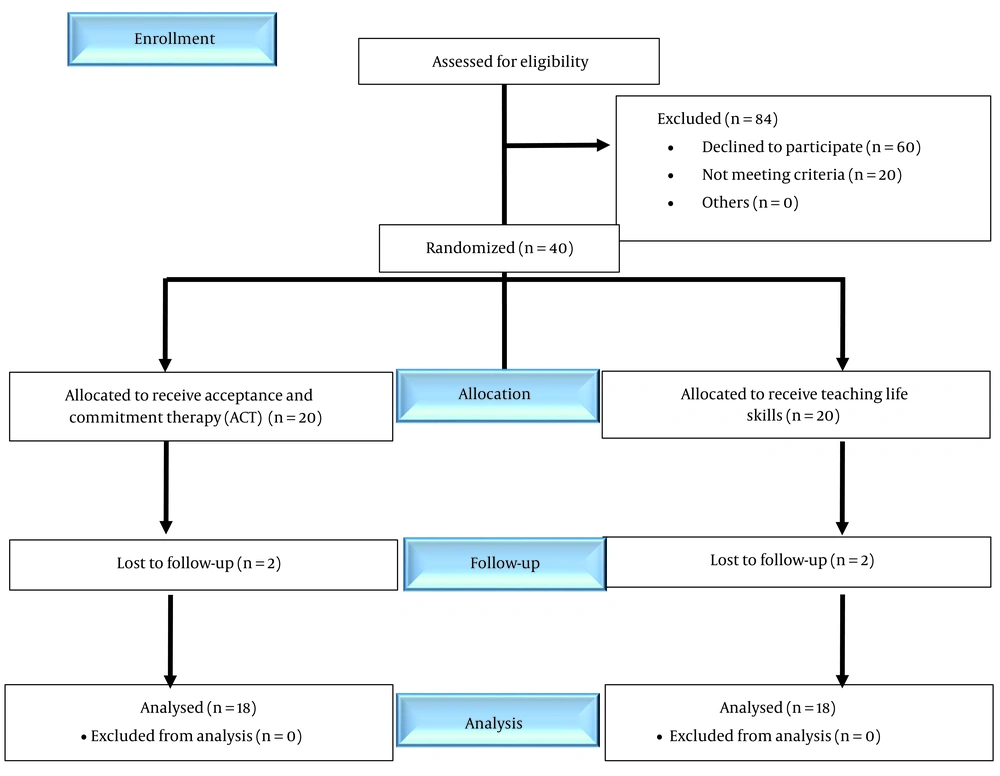

This clinical trial utilized a pretest-posttest-follow-up design with a control group. The study population consisted of adolescents aged 13 to 18 years diagnosed with T1D who were referred to an endocrinologist at Beheshti Hospital in Kashan during the summer and autumn of 2023. To determine the sample size, G*Power 3.1 software was used. Based on repeated measures analysis of variance, an effect size of 0.53 was chosen based on a similar study (24), with a type I error rate of 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.80. For two groups and three measurements, a total sample size of 32 participants (16 per group) was determined. Considering the potential for sample attrition and limited resources, the sample size was increased to 40 participants. However, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, four participants were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 36 individuals (Figure 1).

Participants were selected through purposive sampling based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, they were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the intervention or control group. The control group received a structured psychoeducational program on life skills, including time management and adolescent health education (e.g., physical and emotional changes during puberty). Designed as a placebo control to account for the potential influence of interpersonal group interaction effects, the program was delivered in eight weekly 60-minute group sessions, matching the format and duration of the ACT intervention. Sessions were delivered using a standardized curriculum. Additionally, participants in the control group were offered the opportunity to attend the ACT sessions after the completion of the study, ensuring ethical equity and access to potential benefits.

Random assignment was conducted using a website designed for psychological experiments and clinical trials (www.randomizer.org). It should be noted that due to the nature of the psychological intervention and in order to minimize bias, the outcome assessor was blinded to participants' group allocation. The intervention group received ACT (25) over eight weekly group sessions, each lasting 60 minutes. A follow-up assessment was conducted three months after the intervention. The collected data were analyzed using repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) across three time points (pretest, posttest, follow-up) using SPSS version 22. Data analysis followed a per-protocol approach. Four participants were excluded during the initial sessions for exceeding the predefined exclusion criterion of missing more than two sessions. Among these, two withdrew due to a relapse of physical illness requiring medical care, and two withdrew due to lack of parental cooperation. The final sample comprised 36 participants (18 per group), corresponding to a 10% dropout rate.

- Inclusion criteria: Informed consent for participation, age between 13 to 18 years at the time of the study, diagnosis of T1D, no history of severe physical illnesses (e.g., cancer, MS) or severe mental disorders (e.g., psychotic disorders), no history of grief disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and oppositional behavior disorder, no participation in regular exercise programs, no concurrent psychological treatment, and no history of substance use within the past 12 months.

- Exclusion criteria: Lack of cooperation in completing the questionnaires, absence from more than two therapy sessions, presence of psychological problems requiring medical treatment, and changes in medication. To screen for severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., psychotic disorders), all participants were evaluated through a structured clinical interview by a licensed psychologist prior to inclusion. Adolescents who met DSM-5 criteria for psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorders were excluded from the study.

3.1. Study Instruments

3.1.1. Beck Anxiety Inventory

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) is a 21-item self-report scale that assesses the severity of anxiety symptoms, particularly focusing on somatic and cognitive components. Cut-offs: 0 - 7 normal, 8 - 15 mild, 16 - 25 moderate, 26 - 63 severe (26). The internal consistency of the scale was reported as 0.92, and its test-retest reliability with a one-week interval was 0.75. The correlation of BAI with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale was 0.25 and 0.51, respectively (26). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of this inventory was reported as 0.87 in the study by Vollestad et al. (27). In Iran, Kaviani and Mousavi found a test-retest reliability of 0.83 and an internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of 0.92 (28). Similarly, Rafiei and Seifi reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 for this inventory (29). The validity of the BAI was assessed through interclass correlation analysis between the BAI scores and clinical expert evaluations of anxiety levels in an anxious population, yielding a correlation of 0.72 (28).

3.1.2. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

This questionnaire was designed by Gross and John to assess emotion regulation strategies in children and adolescents (30). The revised short form comprises 10 items measuring two primary strategies: Reappraisal and suppression, with responses on a 7-point Likert scale. It is divided into two sections: Reappraisal (6 items) and suppression (4 items). Gross and John reported satisfactory validity and reliability, with an internal consistency coefficient of 0.73 and test-retest reliability of 0.69 for both strategies (30). In Iran, this test was normed and validated by Lotfi et al. Factor analysis showed two factors: Reappraisal and suppression. The Cronbach’s alpha for the entire questionnaire was 0.81, and for reappraisal and suppression, it was 0.79 and 0.68, respectively (31).

3.1.3. Intervention

This group intervention is grounded in ACT (25), a third-wave behavioral approach that employs experiential and creative methods — such as painting, clay modeling, and role-play — to facilitate adolescent engagement with ACT processes in a developmentally appropriate manner. Artistic expression allows for the exploration of internal experiences without becoming entangled in verbal reasoning. The eight structured sessions are designed to enhance psychological flexibility through mindfulness, values clarification, and committed action (Table 1) (25).

| Sessions | Content of Sessions |

|---|---|

| First | Getting to know the group; reassuring the group (including nondisclosure of participants' information); personal introduction (a way to melt the ice and feel more belonging to the group); drawing values as an individual task and group discussion; homework and games |

| Second | Homework review; introducing the life manual; being aware of conflict with difficult thoughts; individual artwork; creative frustration; group discussion; learn not to be involved and inclined towards thoughts; homework |

| Third | Homework review; control is difficult experience forgetting on purpose group activity; the experience of being willing and accepting by letting go of the rope artistic activity; homework for this week |

| Fourth | Review homework; release the rope; your mind is like a metaphor artistic activity; publishing difficult and uncomfortable thoughts; artistic activity |

| Fifth | Homework review; moving towards values using the metaphor of passengers on a bus; the role of play in life in artistic activity; homework |

| Sixth | Homework review; value discussion considering the values of the elderly (group discussion); create a value with art work in clay |

| Seventh | Review of last week's content; drawing a road map, a life path to achieve values and a series of committed actions to achieve it; drawing and writing committed actions |

| Eighth | Group discussion about the artwork and how it was; creating a piece of poetry or writing to reflect experiences |

4. Results

A total of 36 participants were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 18 each): An experimental group (9 boys, 11 girls) and a control group (13 boys, 7 girls). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2.

| Variables | Experimental Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 14.40 | 14.86 |

| Gender (boys/girls) | 9.9 | 13.5 |

| Duration of diabetes (y) | 2.16 | 3.56 |

| Family history (yes) | 13 | 15 |

Descriptive statistics for each variable, including anxiety and emotion regulation (reappraisal and suppression), across different assessment stages are presented in Table 3. A repeated measures MANOVA was conducted to analyze the data, and the test assumptions were checked. There was no significant difference between the covariance matrices of the groups (P > 0.05). Bartlett’s test indicated significant correlations among the dependent variables (P < 0.05), and Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variances (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Experimental Group | Control Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | |

| Anxiety | 48.00 (5.04) | 40.45 (65) | 39.90 (4.15) | 50.70 (2.67) | 50.40 (2.81) | 50.85 (3.06) |

| Reappraisal | 22.30 (4.73) | 30.05 (5.04) | 30.00 (4.56) | 22.20 (3.67) | 22.25 (3.61) | 22.90 (4.07) |

| suppression | 15.80 (2.09) | 12.50 (3.31) | 12.70 (3.14) | 17.20 (2.19) | 17.30 (2.43) | 17.20 (2.54) |

| Total emotion regulation score | 38.10 (3.81) | 42.55 (5.81) | 42.70 (5.44) | 39.40 (4.52) | 39.55 (4.46) | 40.10 (5.14) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

As shown in Table 4, ACT had a significant effect on both anxiety and emotion regulation (P < 0.05). Table 5 illustrates significant differences between the groups at pre-test, post-test, and follow-up stages for all variables (P < 0.05). Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to further examine these differences, as reported in Table 6.

| Variables | Effect | Statistic | Values | F | df | P-Value | ηp2 | (1 - β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Time × group | Pillai's trace | 0.88 | 14.38 | 37 | 0.0001 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

| Wilks' lambda | 0.11 | 14.38 | 37 | 0.0001 | 0.88 | 1.00 | ||

| Reappraisal | Time × group | Pillai's trace | 0.92 | 219.90 | 37 | 0.0001 | 0.92 | 1.00 |

| Wilks' lambda | 0.07 | 219.90 | 37 | 0.0001 | 0.92 | 1.00 | ||

| Suppression | Time × group | Pillai's trace | 0.30 | 8.12 | 37 | 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.94 |

| Wilks' lambda | 0.69 | 8.12 | 37 | 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.94 |

| Variables; Statistic (Anxiety × Group) | Error | MS | F | P-Value | Effect Size | (1 - β) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Sphericity | 2 | 202.70 | 167.82 | 0.0001 | 0.81 | 1.00 |

| Greenhouse-geisser | 1.53 | 264.39 | 167.82 | 0.0001 | 0.81 | 1.00 |

| Huynh-feldt | 1.62 | 249.16 | 167.82 | 0.0001 | 0.81 | 1.00 |

| Lower bound | 1.00 | 405.41 | 167.82 | 0.0001 | 0.81 | 1.00 |

| Reappraisal | ||||||

| Sphericity | 2 | 181.30 | 270.88 | 0.0001 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

| Greenhouse-geisser | 1.78 | 203.60 | 270.88 | 0.0001 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

| Huynh-feldt | 1.91 | 189.68 | 270.88 | 0.0001 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

| Lower bound | 1.00 | 362.60 | 270.88 | 0.0001 | 0.87 | 1.00 |

| Suppression | ||||||

| Sphericity | 2 | 35.43 | 15.22 | 0.0001 | 0.28 | 0.99 |

| Greenhouse-geisser | 1.12 | 63.08 | 15.22 | 0.0001 | 0.28 | 0.97 |

| Huynh-feldt | 1.16 | 60.86 | 15.22 | 0.0001 | 0.28 | 0.98 |

| Lower bound | 1.00 | 70.86 | 15.22 | 0.0001 | 0.28 | 0.96 |

| Variables | MD | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | 3.92 | 0.21 | 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | 3.97 | 0.30 | 0.0001 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | 0.05 | 0.20 | 1.00 |

| Reappraisal | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | -3.90 | 0.18 | 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | -4.20 | 0.20 | 0.0001 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | -0.30 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Suppression | |||

| Pre-test | |||

| Post-test | 1.60 | 0.41 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 1.55 | 0.40 | 0.001 |

| Post-test | |||

| Follow-up | -0.05 | 0.11 | 1.00 |

emotion regulation — reappraisal and suppression — showed significant improvements across the three stages, indicating that ACT effectively enhanced emotion regulation in participants. These changes are reflected in the mean scores reported in Table 3.

Specifically, anxiety significantly decreased in the ACT group over time (F(2, 37) = 14.38, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.81), with post-test and follow-up scores both showing large improvements compared to pre-test (3.92 ± 3.97, respectively). Reappraisal scores also increased significantly (F(2, 37) = 219.90, P < 0.0001, ηp2 = 0.87), while suppression scores decreased (F(2, 37) = 8.12, P = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.28). These results reflect large to medium effect sizes and high statistical power.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the impact of ACT on anxiety and emotion regulation in adolescents with T1D. Findings indicated that ACT significantly reduced anxiety and improved emotion regulation, with partial eta-squared (ηp2) values in this study (0.28 - 0.87) indicating medium to large effect sizes based on standard benchmarks (32). Comparable ACT studies with adolescents have reported ηp2 values of 0.29 - 0.31 for behavioral outcomes (33) and 0.22 - 0.48 for functional outcomes (34).

Adolescents with T1D often experience emotional distress related to the burden of illness, which negatively affects treatment adherence and glycemic control (18, 19, 22, 23). This may be attributed to the psychological burden of living with a chronic illness, which can impair self-management, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and social functioning. Consequently, anxiety symptoms are frequently associated with poor adherence and suboptimal glycemic control in adolescents with T1D (35).

The efficacy of ACT in reducing anxiety in this population may stem from its core mechanism of enhancing psychological flexibility (15, 36). Rather than aiming to eliminate distress, ACT fosters acceptance of illness-related thoughts and emotions while promoting engagement in value-driven behaviors. This is particularly critical for adolescents with T1D, who often face emotional distress that undermines self-care (35). The ACT processes — such as cognitive defusion and committed action — facilitate adaptive coping and diminish avoidance, thereby improving emotion regulation and treatment adherence (12, 23).

Another finding was that ACT enhanced emotion regulation (reappraisal and suppression) in participants. This aligns with research by Yuan et al. and Iri et al. (20, 21). Although suppression is generally considered a maladaptive strategy, the reduction in suppression scores observed in this study indicates an improvement in suppression-related difficulties rather than an increase in suppression itself, and may reflect increased psychological flexibility — a central process in ACT. While ACT promotes openness and acceptance, it does not rigidly reject suppression; instead, it encourages the flexible use of emotion regulation strategies aligned with personal values. This interpretation is supported by research indicating that ACT facilitates deliberate, context-sensitive emotion regulation rather than rigid suppression or avoidance (15, 37). In specific contexts, controlled suppression may serve adaptive functions. From this perspective, reduced suppression may reflect enhanced self-awareness and value-consistent emotional modulation, consistent with ACT principles (38).

Moreover, the potential for social desirability bias in self-reports cannot be excluded. Future research should incorporate observational or physiological measures to more accurately assess these effects. Emotion reappraisal, in contrast to suppression, is linked to more positive affect, healthier relationships, and higher self-esteem and life satisfaction. Therefore, interventions that enhance reappraisal are particularly valuable. The ACT facilitates this through value clarification and committed action. By guiding clients to identify core values, set realistic goals, overcome internal barriers, and act consistently with these values, ACT promotes deeper satisfaction and resilience. This process enables individuals to break free from maladaptive emotional cycles such as anxiety and despair, thereby enhancing cognitive emotion regulation (15, 30).

Reappraisal is further supported through cognitive defusion, a core ACT process, which reduces rigid emotional responses by helping individuals distance themselves from thoughts and adopt flexible strategies such as reappraisal (15, 36).

5.1. Psychological Flexibility Model of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

According to the psychological flexibility model of ACT (15), enhanced emotional functioning emerges through processes such as cognitive defusion and values-based action. Cognitive defusion diminishes the literal influence of distressing thoughts, while values-based action fosters committed behaviors consistent with personal meaning. These mechanisms are particularly pertinent to adolescents with T1D, who frequently encounter illness-related cognitive distress. The observed reductions in anxiety and improvements in emotion regulation in this study may reflect an increased capacity to respond flexibly to internal experiences.

Although the model offers a robust theoretical framework, empirical mediation research in pediatric diabetes remains scarce and warrants further exploration. Beyond its psychological impact, ACT may confer physiological benefits relevant to diabetes management. By alleviating chronic stress and strengthening psychological flexibility, ACT may help regulate HPA axis activity, reduce cortisol secretion, and indirectly decrease insulin resistance (8, 15). Furthermore, improved emotion regulation may lower systemic inflammation, a critical factor in immune dysfunction and diabetes-related complications (36, 37). These pathways suggest that ACT can support metabolic health in parallel with enhancing emotional well-being.

5.2. Conclusions

This study provides preliminary yet compelling evidence supporting the use of ACT as a promising psychosocial intervention to reduce anxiety and enhance emotional functioning among adolescents with T1D.

5.3. Practical Recommendations

The ACT can be implemented as a supportive intervention for adolescents with T1D in clinical or school settings. Training healthcare providers in ACT and involving families may enhance adherence and emotional well-being. Telehealth delivery could expand access in underserved regions.

5.4. Recommendations

Long-term studies are needed to assess ACT’s impact on glycemic control, using objective measures such as HbA1c. Comparative trials with other therapies and diverse cultural contexts are also recommended to strengthen generalizability.

5.5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample, limited to adolescents from a single city in Iran, may restrict generalizability, and cultural factors such as family dynamics, social stigma, and attitudes toward psychological treatment should be considered in culturally adapted interventions. The three-month follow-up may be insufficient to assess the long-term effectiveness of ACT in T1D; extended follow-up (6 - 12 months) is recommended. Reliance on self-report measures introduces potential bias, and the use of the BAI may confound results due to overlap with diabetes-related somatic symptoms; diabetes-specific tools like the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) Scale are advised. Finally, the absence of comparison with other therapies highlights the need for larger, more diverse comparative trials to determine ACT’s relative efficacy.