1. Background

Psychosocial stress is a critical determinant of mental health and a major risk factor for psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance use disorders. It refers to the complex mental and physiological responses that individuals experience when they perceive a threat or challenge that exceeds their coping resources (1). It is not solely the nature of external events that induces stress, but rather how individuals interpret and react to them — particularly in situations marked by uncertainty, lack of control, or insufficient information (2). Within the field of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, psychosocial stress is not only a consequence of life adversity but also a clinically significant contributor to the onset, course, and severity of psychiatric illnesses.

Clark et al. categorize psychosocial stress into two broad domains: Psychological and social-behavioral. Psychological stress, frequently encountered in clinical psychiatry, arises from chronic uncertainty, emotional overload, and perceived lack of meaning — all of which are associated with mood and anxiety disorders. Social-behavioral stress, in contrast, is driven by isolation, role strain, and perceived injustice — factors that often contribute to behavioral dysfunction and psychiatric morbidity. These stressors are embedded within the interplay between internal emotional states and the external social environment — workplace dynamics, interpersonal relationships, and societal conditions all play a role (3).

On an individual level, characteristics such as neuroticism, low self-esteem, and prior trauma can increase vulnerability to stress (4). These are well-established risk factors in psychiatric research. However, social determinants — including interpersonal conflict, lack of social support, and community-level instability — often exacerbate these internal vulnerabilities (1). The growing emphasis on social determinants in psychiatric research highlights how environmental and structural stressors shape population mental health. Chronic psychosocial stress is also associated with neurocognitive changes and behavioral dysfunction, which are relevant to clinical psychiatry and neuropsychiatry. Broader environmental conditions such as poverty, economic disparity, and political upheaval further intensify stress by restricting access to essential resources (5).

Cultural expectations also influence stress levels. In societies with rigid gender roles and heightened performance demands, individuals — particularly women — may experience disproportionate psychological burdens (6). The chronicity of such stress is linked not only to poor mental health outcomes — including anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairments — but also to physical illnesses like cardiovascular disease and immune system dysfunction (7).

In the global context, psychosocial stress has emerged as a major public health concern, particularly in urban environments marked by fast-paced lifestyles, technological overload, and social isolation (8). In low- and middle-income countries, additional stressors — such as political instability and limited access to healthcare — further compound this burden (9).

Iran presents a unique case. Economic sanctions, political tensions, and inflation have created a backdrop of persistent stress for many Iranians (10). In Tehran — the country’s most densely populated urban center — residents face mounting financial insecurity, unemployment, and a rapidly transforming cultural and social landscape. Traditional support structures are eroding, and expectations surrounding gender roles and family obligations continue to place disproportionate pressure on women (11).

According to a landmark study by Noorbala et al., 82.7% of Tehran residents had experienced at least one major stressful life event in a single year, with the most common sources of stress being related to family health, economic insecurity, and concerns about the future (12). Given these widespread challenges, identifying the most pressing stressors — and understanding how social determinants such as gender, socioeconomic status (SES), and life satisfaction interact with them — is vital for informing mental health interventions and public policy.

2. Objectives

This study bridges psychiatry, psychology, and social science by examining psychosocial stress as a behavioral and psychiatric outcome shaped by environmental and demographic factors. It aims to identify the most common psychosocial stressors experienced by adult residents in Tehran in 2023 and to examine the social determinants associated with severe stress. Understanding these psychiatric and behavioral implications can inform evidence-based policies, preventive mental health strategies, and interventions tailored to high-risk urban populations.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Study Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted in 2023 among residents of Tehran aged 18 years and older. However, research and method sampling were described elsewhere (12, 13). Briefly, proportional stratified random sampling was employed to recruit 1,008 participants. This sample size was calculated based on a confidence level of 95%, the experience of stress among 80% of citizens (based on previous studies), as well as accounting for a 10% error in the rate of stress experiences and a 15% dropout rate. According to the statistical formula, the sample size was 112 individuals for each of the three age groups from three socioeconomic areas (R). Tehran was stratified into four districts based on developmental status: Fully developed, developed, less developed, and requiring intervention. Each district served as a separate stratum. Subsequently, three neighborhoods were randomly selected from each district. Participants were then recruited from various public locations within these neighborhoods where individuals commonly congregate for daily activities, including bus stops, subway stations, department stores, banks, mosques, healthcare centers, libraries, universities and campuses, restaurants, and parks.

3.2. Measures

The main outcome was considered to be psychosocial stress. We assessed psychosocial stress using a questionnaire on stressful events. This questionnaire was developed and validated by Noorbala et al. This instrument has been previously published (12). This comprehensive tool evaluates various types of psychological and social stressors across different categories, including personal, family-related, economic, social, and educational. The questionnaire's design allows for a multifaceted assessment of stressful events, providing a nuanced understanding of the stressors experienced by the study population.

3.3. Data Collection

Data collection was carried out by ten trained interviewers, each of whom received a one-day training session on the objectives of the study and the proper administration of the questionnaire. Based on the selected neighborhoods, each interviewer conducted face-to-face assessments using a standardized checklist to document stressful social and psychological events, following the acquisition of informed consent from participants. In addition, demographic information was collected using a separate, purpose-designed checklist. The main inclusion criteria for participation in this study were: (1) Being 18 years of age or older, and (2) providing informed consent.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the characteristics of participants by sex, age, SES, and other variables. We also examined the associations between variables using bivariate and multiple logistic regression tests. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 25).

4. Results

Of the study participants, 50.6% were male, 36.4% were married, and 41.0% held a bachelor's degree. Approximately half (49.5%) were employed, while 18.2% were unemployed (Table 1).

| Demographic Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 490 (50.6) |

| Female | 470 (48.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 479 (49.5) |

| Married | 352 (36.4) |

| Divorced | 51 (5.3) |

| Widowed | 38 (3.9) |

| Education level | |

| Elementary, middle, and high school | 72 (7.4) |

| Diploma | 178 (18.4) |

| Bachelor | 132 (13.6) |

| Associate's degree | 397 (41.0) |

| Master | 152 (15.7) |

| PhD | 26 (2.7) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 479 (49.5) |

| Unemployed | 157 (18.2) |

| Housewife | 87 (9.0) |

| Retired | 85 (8.8) |

| Others | 149 (15.4) |

To identify the most prevalent psychosocial stressor events, the frequency of these events over the past year was assessed. As shown in Table 2, the most commonly reported stressors included concerns about personal or family future (57.6%), inflation, rising prices, and market instability (57.1%), and worries about financial and economic prospects (55.0%).

| The Most Common Events Producing Psychosocial Stress | Prevalence Percentage |

|---|---|

| Concerns about personal and family future (e.g. fear of sickness, death, addiction, unemployment and other social issues for children or brother or sister, failure to do personal affairs in the future) | 57.6 |

| Inflation, rising prices, and market instability | 57.1 |

| Concerns about financial and economic future (e.g. fear of bankruptcy or future poverty) | 55.0 |

| Expensive housing | 43.4 |

| Concerns about future of employment (e.g. fear of joblessness, being fired, failure to do business responsibilities) | 40.7 |

| Concerns about health of a family member (father, mother, sister, brother, spouse, and child) | 39.2 |

| Traffic problems | 38.3 |

| Dissatisfaction with facial appearance, height, weight, and other aspects of appearance, or concern about their unfavorable changes (such as aging, becoming overweight or underweight, becoming unattractive, hair loss, etc.). | 35.6 |

| Dealing with unforeseen expenses (such as illness, marriage, and theft) | 35.4 |

| Changes in sleep habits | 35.2 |

| Salary and wage problems | 35.1 |

| Low socioeconomic and cultural level of the neighborhood | 35.0 |

| Unemployment | 34.8 |

| Internet-related issues (including filtering, slowness, disconnection, and lack of sufficient coverage) | 34.2 |

| Air, noise, and food pollution | 32.1 |

| Death of main family members | 31.2 |

| High educational costs and expenses for family members | 31.0 |

| Uncertainty of people's real point of view | 30.5 |

| High crime (such as robbery and murder) and low sense of security in the neighbourhood and society | 27.8 |

| Ccorruption in the police, court, government offices and institutions, municipality, and the like | 27.6 |

Table 3 summarizes the psychosocial stressor events reported to have caused severe stress among participants. The findings indicate that future-related concerns were strongly associated with elevated stress levels. The most commonly reported severe stressors were concerns about the health of family members (14.4%), uncertainty about the personal or family future (13.2%), and apprehension about the financial and economic outlook (12.7%). Overall, 45.6% of participants reported experiencing at least one severe stressor. Economic stress was reported by 32.3% of participants, while 28.8% experienced at least one severe family-related stressor. Additionally, 25.7% of the sample reported a severe health-related stressor, and an equal proportion (25.7%) experienced at least one severe future-related stressor.

| Events Producing Psychosocial Stress | Severe Stress (%) |

|---|---|

| Concerns about personal and family future | 39.4 |

| Inflation, rising prices, and market instability | 38.7 |

| Concerns about financial and economic future | 38.1 |

| Expensive housing | 31.1 |

| Concerns about future of employment | 26.8 |

| Salary and wage problems | 20.5 |

| Internet-related issues | 19.7 |

| Concerns about health of a family member | 19.5 |

| High educational costs and expenses for family members | 18.9 |

| Traffic problems | 18.3 |

| Unemployment | 18.2 |

| Dealing with unforeseen expenses | 18.1 |

| Concerns about educational future | 17.7 |

| Uncertainty of people's real point of view | 15.0 |

| Death of main family members | 14.7 |

| Low socioeconomic and cultural level of the neighborhood | 14.4 |

| Unfavorability of domestic and foreign policies | 14.4 |

| Concerns about future of society and community | 13.7 |

| Ccorruption in the police, court, government offices and institutions, municipality, and the like | 13.3 |

| Dissatisfaction with quality of housing | 13.3 |

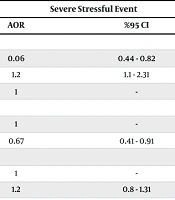

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with experiencing severe psychosocial stress in the past year (Table 4). The final model adjusted for potential confounders, including sex, age, SES, and marital status. The results indicated that both social interaction and life satisfaction were statistically significant predictors. Specifically, higher levels of social interaction were associated with a lower likelihood of experiencing severe psychosocial stress (P < 0.001, OR = 0.48). Additionally, greater life satisfaction was significantly associated with reduced odds of experiencing psychosocial stress over the past year.

| Characteristics | Severe Stressful Event | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | %95 CI | ||

| Age (y) | 0.001 | ||

| 20 - 39 | 0.06 | 0.44 - 0.82 | |

| 40 - 59 | 1.2 | 1.1 - 2.31 | |

| 60+ | 1 | - | |

| Marital status | 0.01 | ||

| Single | 1 | - | |

| Married | 0.67 | 0.41 - 0.91 | |

| Sex | 0.5 | ||

| Male | 1 | - | |

| Female | 1.2 | 0.8 - 1.31 | |

| Social interaction (last 12 mo) | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 0.48 | 0.2 - 0.8 | |

| No | 1 | - | |

| Life satisfaction | 0.01 | ||

| Yes | 1 | - | |

| No | 2.11 | 1.9 - 3.3 | |

| SES | 0.02 | ||

| High | 0.58 | 0.42 - 0.85 | |

| Low | 1 | - | |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; SES, socioeconomic status.

5. Discussion

This study examined the prevalence and determinants of psychosocial stressors among adult residents of Tehran in 2023. The findings revealed a high burden of stress, with the most commonly reported stressors being concerns about the personal or family future (57.6%), inflation and market instability (57.1%), and financial insecurity (55.0%). These results are consistent with previous findings by Noorbala et al., who reported that over 80% of Tehran residents experienced at least one severe stressor annually — primarily related to family well-being and economic uncertainty (12). The slight increase in prevalence observed in the present study may reflect growing anxieties fueled by ongoing macroeconomic instability and sociopolitical tensions in Iran.

Economic-related stressors emerged as the most prominent theme, underscoring the central role of financial instability in shaping psychological well-being in urban environments. This trend aligns with prior research, including the Tehran Cohort Study, which reported a 37.1% prevalence of mental health disorders — particularly among women (45%) — and linked these outcomes to factors such as high living costs, traffic congestion, and environmental degradation. These findings reinforce the well-established association between chronic structural stressors and adverse mental health outcomes, especially within densely populated urban areas. Global evidence similarly links economic uncertainty to heightened levels of depression and anxiety, particularly in cities undergoing rapid socioeconomic change (14).

Notably, the results of this study identified two key protective factors against psychosocial stress: Social interaction and life satisfaction. Participants with stronger social ties reported significantly lower levels of severe stress (OR = 0.48, P < 0.001), echoing previous research that emphasizes the buffering role of social capital in stressful environments. Social connectedness has consistently been associated with lower morbidity and mortality, particularly in high-stress settings (15). For example, studies involving older adults in Tehran and earthquake survivors in Iran have shown that perceived social support and community cohesion can substantially reduce psychological distress and post-traumatic symptoms (16).

Similarly, higher life satisfaction was associated with reduced odds of experiencing severe stress. Participants with lower satisfaction scores were more than twice as likely to report severe stress (OR = 2.11, P = 0.01). These findings are consistent with national data from Iran, which identify income, employment, and educational attainment as key predictors of subjective well-being. Globally, life satisfaction is widely recognized as a protective factor that enhances psychological resilience and lowers the risk of stress-related disorders (17). Given the growing body of evidence linking life satisfaction with resilience to stress, enhancing overall quality of life must be a central component of public mental health interventions.

Demographic variables also played a role in stress exposure. Married individuals reported significantly lower levels of stress compared to their unmarried counterparts [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.67, P = 0.01], potentially reflecting the emotional and financial support available within marital relationships. Interestingly, gender was not a significant predictor of severe stress in the final model. This contrasts with findings from prior studies that have identified greater stress burdens among women, often attributed to caregiving responsibilities and cultural expectations. The lack of gender disparity observed in this study may point to a growing universality of stress exposure across social groups, particularly in the face of widespread economic pressures.

These results underscore the multifaceted nature of psychosocial stress in urban Iran, highlighting the need to address both individual-level and structural determinants. In particular, economic insecurity, housing instability, and employment uncertainty emerge as key stressors requiring systemic intervention. Urban populations consistently report higher rates of psychiatric morbidity due to overcrowding, financial strain, and social fragmentation (16-18). Addressing these stressors demands coordinated public health strategies that extend beyond individual coping mechanisms.

This study reveals a high prevalence of psychosocial stress among adults in Tehran, with the most pressing stressors rooted in economic instability, concerns about the future, and inflation. These stressors reflect deeper structural issues that affect quality of life and mental well-being in Iran’s largest urban centers. Crucially, the findings also emphasize the protective value of social and psychological resources. Strengthening social networks, fostering community cohesion, and improving overall quality of life — particularly through equitable access to education, employment, and healthcare — should be central components of mental health interventions. To effectively reduce the mental health burden in urban Iran, policymakers must adopt a dual approach: Implementing macroeconomic reforms to mitigate structural stressors, and promoting psychological resilience through targeted support and well-being programs. Addressing psychosocial stress is essential not only for individual mental health, but also for enhancing community resilience and fostering long-term social development.

This study has several notable strengths. It is among the few large-scale, population-based investigations of psychosocial stress in Tehran, conducted across all 22 municipal districts using a stratified, multi-stage cluster sampling design. This approach ensured a broad representation across socioeconomic and demographic groups, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. The use of a culturally validated instrument further allowed for contextually relevant assessment of stressors, capturing the lived experiences of Tehran’s residents. The study also provides timely data during a period of considerable economic and political uncertainty, offering valuable insights for public health planning and mental health policy in Iran.

Despite its strengths, this study has limitations. Its cross-sectional design limits causal inference, precluding conclusions about the temporal relationship between stressors and outcomes. Longitudinal studies would be better suited to capturing the evolution and cumulative effects of psychosocial stress over time. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data introduces the potential for recall bias and social desirability bias, especially when reporting sensitive information about mental and emotional distress. Although the sample is representative of Tehran’s urban population, the findings may not generalize to rural areas or other Iranian cities, where stressors and coping mechanisms may differ. Finally, while the survey covered a broad spectrum of stress domains, emerging stressors — such as digital overload, climate anxiety, or experiences of structural discrimination — may not have been fully captured.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights a high prevalence of psychosocial stress among adults in Tehran, Iran, with economic instability, future uncertainty, and inflation emerging as predominant stressors. Protective factors such as social interaction and life satisfaction were significantly associated with reduced stress levels. These findings emphasize the need for multifaceted public health strategies that combine structural economic reforms with community-level interventions aimed at enhancing social cohesion and individual well-being. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to better understand causal pathways and stress trajectories in urban populations.