1. Background

Adolescence is a critical, sensitive, and significant period in human development. One of the most prevalent emotional challenges during this stage is social anxiety, the early onset of which impacts an individual’s psychological and social life, for instance, creating difficulties in peer relationships, participation in group and school activities, and most social executive tasks (1). Timely diagnosis and treatment of this disorder in childhood or adolescence contribute to the development of individual, educational, and social capacities and abilities (2).

Social anxiety, recognized as a social problem affecting adolescents’ mental, emotional, and social well-being (3, 4), causes adolescents to fear encounters with unfamiliar individuals and being evaluated by them, culminating in intense distress and anxiety. They avoid these situations or endure them with significant anxiety, and are also apprehensive of being scrutinized and ridiculed (5, 6). Socially anxious adolescents exhibit fewer social interactions compared to their peers, experience numerous difficulties in coping with environmental and social demands, and demonstrate lower adaptability to their surroundings (7). According to published statistics, the prevalence of social anxiety ranges from 19% to 33% among adolescents and young adults, and from 3% to 13% among adults (8).

Developmental psychologists assert that understanding normative development during adolescence provides profound insights into the mechanisms leading to the persistence of socio-emotional disorders during this period. Identity formation is one such normative developmental process during adolescence. Despite newer theories, Erikson’s theory remains relevant. According to Erikson, adolescents transit from a state of identity confusion toward identity cohesion during this period. The process of achieving a cohesive identity in adolescence is so significant that it encompasses all aspects of an individual’s future life. Consequently, there is considerable interest in examining the relationship between adolescent mental health and identity development. Researchers believe that there is a close and reciprocal relationship between these two. If an individual does not achieve a cohesive identity in adolescence, the groundwork for socio-emotional problems is laid, and conversely, if an individual has such disorders, their identity acquisition process is hindered (9). Therefore, investigating the factors contributing to the formation, perpetuation, and predisposition of emotional disorders, particularly social anxiety disorder, provides crucial insights into understanding these disorders during this period. Considering these factors offers remarkable assistance to adolescents in achieving a cohesive identity, from educational, preventive, and even therapeutic perspectives. In this regard, factors such as attachment styles, ego strength, and mentalization capacity are among essential developmental factors that, if not properly developed, create numerous socio-emotional problems for the individual, particularly during adolescence and identity acquisition. From a developmental psychopathology perspective, disruptions in identity formation during adolescence may interact with relational and intrapsychic vulnerabilities, creating a fertile ground for socio-emotional disorders such as social anxiety.

Attachment theory addresses early social experiences that are effective in an individual’s cognitive and emotional development. In recent decades, numerous studies have explored the causes or persistence of mental disorders from an attachment perspective. For example, Ozturk et al. (10) found a significant relationship between social anxiety and adolescents’ attachment styles. Another study (11) suggested the crucial role of attachment in social anxiety disorder and avoidant personality disorder. Individuals who have been deprived of a caregiver responsive to their physical and emotional needs in childhood are more likely to develop insecure attachment styles, and because they have internalized anxiety about the caregiver’s responsiveness, they experience a sense of detachment from internalized parental images in unfamiliar situations. Manning et al. (12) stated that consistent and sensitive interactions with caregivers and significant others, particularly in response to stress, can lead to secure attachment and the development of an internal working model of the self as a capable and lovable person, and of others as caring and dependable individuals. Anxious attachment style is associated with a negative mental model of the self, meaning that individuals with an anxious attachment style do not perceive themselves as lovable. Avoidant attachment style, on the other hand, is associated with a negative mental model of others, meaning that individuals with this attachment style perceive others as untrustworthy and rejecting. Research indicates that an internal working model that includes the expectation of rejection by others in social situations may culminate in anxiety in social situations. Such maladaptive internal working models can be conceptualized as predisposing factors that shape adolescents’ vulnerability to social anxiety by influencing how social threats are anticipated and interpreted.

Ego strength refers to the ability to maintain one’s identity regardless of psychological stressors, suffering, and conflicts between internal needs and external demands; in other words, the ability to maintain ego stability is based on a relatively stable set of personality traits, which is reflected in the ability to maintain mental health (13). In fact, ego strength represents an individual’s capacity to tolerate stress without experiencing debilitating anxiety. A strong ego leads individuals to exhibit fewer symptoms of psychological trauma and to have sufficient tolerance and capacity to withstand the tensions stemming from life’s stressful conditions. Conversely, a weak ego causes individuals to retreat into their inner world and escape from the external world, giving rise to withdrawal and an inability to cope with life’s problems. According to Freud, ego strength refers to the ability to manage the demands of the id, superego, and environmental requirements, and to manage these conditions. However, sometimes the conflicts arising from the id and superego are so severe that they can create anxiety in the individual. In this state, the individual expends a great deal of energy to prevent unwanted impulses from entering consciousness (14). Previous studies have revealed that ego strength has a significant correlation with the flexibility of defense mechanisms, confidence in social interactions, reduced anxiety in social situations, greater skill in managing social anxiety, and better social functioning (15-17). Clark and Wells (18) presented a cognitive model of social phobia focusing on the ego’s role in managing social anxiety, with the main conclusion being that the ego’s ability to manage social anxiety is influenced by cognitive factors, such as negative self-belief and self-focused attention. In this sense, ego strength may function as a key perpetuating mechanism, determining adolescents’ capacity to regulate anxiety, manage internal conflicts, and maintain psychological coherence in socially evaluative situations.

Alongside attachment styles and ego strength, another factor influencing social anxiety is mentalization capacity, which has gained attention from researchers in recent years (19). Mentalization refers to the capacity to understand one’s own and others’ feelings, needs, desires, and goals. Fonagy et al. believe that successful social functioning depends on accurate reasoning about one’s own and others’ beliefs, intentions, desires, and emotions, and that individuals with social anxiety disorder have deficits in mentalization ability (20, 21). Fear of negative evaluation and the mental states they attribute to others, and misinterpretation of others’ intentions and thoughts, are considered central to social anxiety. Accordingly, it appears that deficits in mentalization play a major role in the conceptualization, development, and maintenance of social anxiety disorder. Mentalization problems can manifest themselves clearly in adolescent behaviors, particularly in their attachments. According to research studies, individuals with social anxiety exhibit reduced mentalization capacity under stressful conditions. In these mental states, experiences appear intensely real, generating high anxiety or leading to avoidance for the individual. Individuals who employ passive coping strategies, such as emotional withdrawal, may maintain mentalization capacity for a longer period; however, when faced with interpersonal stressors, they become emotionally distant. Under conditions of high stress, these strategies fail, leading to the reactivation of feelings of insecurity, intense negative representation of the self, and increased internal stress. Research demonstrates that these individuals experience heightened anxiety symptoms and may exhibit both a distinct deficit in mentalization and a tendency toward hypermentalization (19). Thus, impairments in mentalization may operate as a central mechanism through which attachment insecurity translates into persistent social anxiety symptoms during adolescence.

Therefore, there seems to be a close relationship between attachment styles and mentalization. Attachment seems to create a context in which mental capacity is developed, and mental capacity, as a mediating factor, can prevent social anxiety. However, attachment insecurity, especially anxious or avoidant attachment styles, predisposes individuals to develop social anxiety by influencing how they perceive social relationships and threats. The mechanism of the attachment effect is as follows: Attachment anxiety causes hyper-activation of the attachment system followed by a fear of rejection and excessive approval-seeking. Then, attachment avoidance causes deactivation of the attachment system followed by discomfort with closeness and fear of dependency. These early patterns form maladaptive internal working models, leading to heightened sensitivity to social evaluation, low self-worth, and fear of negative judgment (22).

According to Peter Fonagy's theory, the capacity for mentalization is formed in the context of attachment. If the attachment style and, consequently, the internal working models are insecure, the formation of this capacity will encounter problems. Impairments in mentalization, especially hyper-mentalizing (over-attributing negative thoughts to others), maintain and exacerbate social anxiety symptoms over time. In social situations, individuals with social anxiety often engage in distorted mentalization (e.g., "Everyone thinks I’m stupid"). Hyper-mentalizing leads to misinterpretation of neutral or ambiguous cues as threatening. Mentalization acts as a cognitive-affective filter that shapes how social information is processed and thus perpetuates maladaptive beliefs and behaviors (23).

To gain a clear understanding of social anxiety disorder, it is essential to consider both predisposing and perpetuating factors within a coherent developmental framework. Given that social anxiety is fundamentally an interpersonal and emotional disorder, attachment styles were conceptualized as predisposing factors in the present study. Ego strength and mentalization capacity were considered perpetuating mechanisms, as their mature development depends on secure attachment relationships. Together, these factors form an integrated pathological model explaining both the emergence and maintenance of social anxiety during adolescence. This path-analytic approach provides novel insights into the interrelations among attachment styles, ego strength, and mentalization capacity in explaining social anxiety during adolescence.

2. Objectives

Although various studies have investigated the relationship between social anxiety and the aforementioned factors, the present study aimed to develop a model of adolescent social anxiety based on attachment styles, ego strength, and mentalization capacity.

3. Methods

The current research employs a correlational design. The study population consisted of all male and female adolescent students in secondary and high schools in the city of Qazvin. The sample size, calculated using Cochran’s formula, was determined to be 380. After attrition, the final sample comprised 152 female and 165 male students. Therefore, out of the 380 questionnaires collected, a total of 317 were included in the study, while 63 questionnaires were excluded due to various issues (38 from female students and 25 from male students). In fact, questionnaires that were incomplete, had a high number of unanswered questions, or had multiple answers for a question were discarded. Also, some questionnaires were not returned by the participants. Of course, the total sample size calculated was based on a 20% dropout rate, which does not cause any problems in the results. A multi-stage stratified random sampling method was used for sample selection. In this process, considering the calculated sample size, the proportion of students in secondary and high schools was initially calculated based on the two urban districts of Qazvin. Subsequently, the proportion of students was calculated based on the secondary and high schools and finally based on the grade level. Ultimately, the study sample was selected using a simple random sampling method from the designated schools based on the calculated proportions at each grade level. It should be noted that the data analyzed in the present study originate from a Master’s thesis dataset that has also been utilized in a previously published article examining the predictive relationships among the study variables using regression analysis. In contrast, the present study applies path analysis to investigate the structural and indirect relationships among variables, representing a distinct analytical and theoretical approach. The statistics regarding the number of students by grade level, educational stage, and gender are presented in Table 1.

| Educational Stage and Grade Level | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary school | ||

| Eighth | 47 (28.48) | 43 (28.28) |

| Ninth | 50 (30.30) | 47 (30.92) |

| Total | 97 (58.78) | 90 (59.22) |

| High school | ||

| Tenth | 33 (20.00) | 32 (21.05) |

| Eleventh | 35 (21.22) | 30 (19.73) |

| Total | 68 (41.22) | 62 (40.78) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

In this study, data were collected using the Social Phobia Inventory (SPI), the Adult Attachment Questionnaire (AAQ), the Psychological Inventory of Ego Strength (PIES), and the Reflective Function Questionnaire (RFQ) among secondary and high school students in Qazvin. Considering the social, cultural, and academic differences among students in Qazvin schools, efforts were made to select students from various schools across different areas of the city to maintain adequate sample dispersion. Subsequently, the aforementioned questionnaires were distributed to male and female students in the selected schools, and only fully completed questionnaires were used in the data analysis process. Inclusion criteria for the study included studying in the secondary or high school, reading and writing literacy, and average and higher-than-average intelligence. Those with a history of severe mental disorders, including psychotic disorders and severe personality disorders, such as borderline and schizotypal personality disorders… and intellectual disability were not included in the study. The diagnosis of these disorders was based on the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-V), and participants showing signs of these disorders or having a history of hospitalization were not included in the study. The exclusion criterion was also defined as incomplete or distorted questionnaires. Path analysis using AMOS software was employed for data analysis.

3.1. The Social Phobia Inventory

This questionnaire was designed by Connor et al. to assess social anxiety. The SPI evaluates three clinical dimensions of social anxiety, including avoidance, fear, and physiological symptoms of the disorder. This questionnaire is a 17-item self-report scale comprised of three subscales: Fear (6 items), avoidance (7 items), and physiological discomfort (4 items). The scoring of this scale is based on a 5-point Likert scale.

The reliability and validity of the SPI have been assessed using the test-retest method, with diagnostic accuracy for social anxiety disorder ranging from 78% to 89%. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this questionnaire has been reported as 94% in a normal population. Additionally, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the subscales of this questionnaire have been reported as 89% for fear, 91% for avoidance, and 80% for physiological discomfort. Connor et al. (24) reported the test-retest reliability of this scale in socially anxious individuals to be between 78% and 89%, and the internal consistency for the total scale was reported as 94% in normal populations. Moreover, in Hassanvand Amouzadeh’s study (25), the Cronbach's alpha of this questionnaire was found to be 0.94, its test-retest reliability was found to be 0.96, and its convergent validity was found to be 0.7. We obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.79 for this questionnaire in our study.

3.2. The Adult Attachment Questionnaire

The AAQ, developed by Hazan and Shaver, consists of 15 items. This questionnaire uses a 5-point Likert scale, with scores of 1 and 5 assigned to responses of “never” and “almost always,” respectively. The questionnaire also comprises three subscales: The first 5 items deal with the insecure-avoidant attachment style, the second 5 items are related to the secure attachment style, and the third 5 items address the insecure-ambivalent attachment style. Hazan and Shaver reported a test-retest reliability of 81% for the total scale and a Cronbach's alpha reliability of 78%. Collins and Read obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 79% for this questionnaire, suggesting high reliability. In another study, acceptable validity and reliability were obtained for this test. Concurrent validity for this questionnaire was obtained in Iran using Cronbach's alpha. Based on the results obtained, this coefficient was determined to be 77%, 81%, and 83% for the secure, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-ambivalent attachment styles, respectively (26). The concurrent validity of Hazan and Shaver’s AAQ with Main’s Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) was found to be 79% for secure, 84% for insecure-avoidant, and 87% for insecure-anxious attachment styles, respectively (27). We obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.86 for this questionnaire in our study.

3.3. The Psychological Inventory of Ego Strength

The PIES was developed by Markstrom et al. to assess eight ego strength points, including competence, fidelity, love, hope, will, purpose, care, and wisdom, comprising 64 items. The questionnaire items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Markstrom et al. confirmed the face, content, and construct validity of the PIES. They also reported the reliability of this questionnaire with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 68%. In a study conducted in Iran, the Cronbach's alpha for the inventory using Iranian samples was found to be 91%, and the split-half reliability of the scale was reported to be 77% (28). The reliability of the PIES in another study in Iran, using Cronbach's alpha, was determined to be 64% (29). We obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.85 for this questionnaire in our study.

3.4. The Reflective Function Questionnaire

The RFQ (20) consisting of 14 items was developed by Fonagy et al. to assess reflective function in research applications. This questionnaire employs a 7-point Likert scale. Fonagy et al. (20) reported the internal consistency of the RFQ for the subscales of “certainty of mental states” and “uncertainty of mental states” to be 65% and 77%, respectively, in a clinical sample, and 67% and 63%, respectively, in a normal sample. The test-retest reliability over a three-week period for the subscales of “certainty of mental states” and “uncertainty of mental states” was reported to be 75% and 84%, respectively. In Iran, Cronbach's alpha for these subscales was found to be 0.88 and 0.66 (30). We obtained a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.77 for this questionnaire in our study.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations of the research variables. This table provides the aforementioned indices by gender and grade level within the sample group.

| Variables | Social Anxiety | Ego Strength | Mentalization (Certainty) | Mentalization (Uncertainty) | Secure Attachment | Avoidant Attachment | Ambivalent Attachment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 33.1 ± 11.4 | 290.2 ± 25.0 | 3.2 ± 3.8 | 6.9 ± 4.1 | 15.4 ± 3.3 | 13.5 ± 3.6 | 11.4 ± 4.3 |

| Male | 32.6 ± 10.1 | 286.0 ± 25.1 | 4.0 ± 3.8 | 4.4 ± 3.9 | 15.5 ± 3.9 | 12.7 ± 3.7 | 12.3 ± 3.6 |

| Eighth | 9.01 ± 17 | 289.2 ± 26.2 | 4.4 ± 3.3 | 5.8 ± 5.0 | 15.4 ± 3.9 | 13.2 ± 3.8 | 12.2 ± 4.3 |

| Ninth | 12.4 ± 18 | 280.1 ± 24.2 | 7.1 ± 4.2 | 5.7 ± 3.7 | 15.0 ± 4.5 | 12.9 ± 4.2 | 12.1 ± 5.3 |

| Tenth | 10.0 ± 18 | 284.3 ± 24.4 | 2.5 ± 3.0 | 6.6 ± 4.0 | 16.2 ± 3.1 | 13.2 ± 3.6 | 12.4 ± 3.4 |

| Eleventh | 10.4 ± 17 | 290.1 ± 25.1 | 3.1 ± 3.6 | 7.0 ± 3.9 | 15.3 ± 3.3 | 13.2 ± 3.4 | 11.1 ± 3.5 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

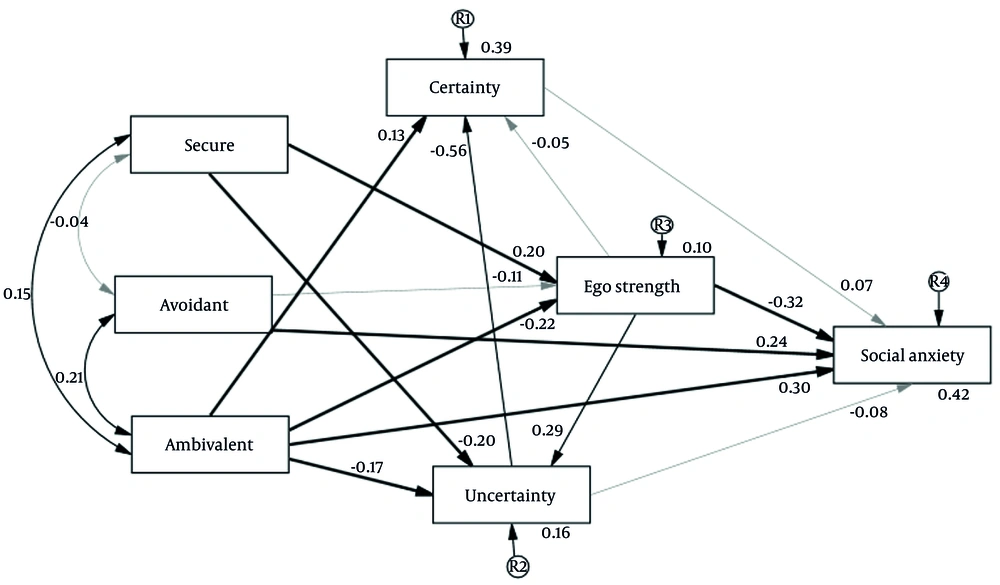

AMOS software was used to examine the tested model while considering the correlations among predictor variables. According to the fitted model [minimum discrepancy of confirmatory factor analysis/degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) = 2.65, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.986, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) = 0.903, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.977, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.089, Akaike information criterion (AIC) = 58.60, Bayesian information criterion (BIC) = 139.18] illustrated in Figure 1 and the coefficients presented in Table 3, with the exception of the four paths indicated in gray, the remaining variables played a significant role in explaining the mediating and endogenous variables of the model. Based on the results obtained in this model, retaining all variables, 39% of the variance in the certainty dimension, 16% of the variance in the uncertainty dimension, 10% of the variance in ego strength, and finally, 42% of the variance in social anxiety were explained.

| Predictor and Dependent Variables a | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | Standard Coefficient | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aav ← ES | -0.734 | 0.456 | -1.61 | -0.108 | 0.107 |

| Aam ← ES | -1.36 | 0.422 | -3.24 | -0.219 | 0.001 |

| As ← ES | 1.41 | 0.461 | 3.05 | 0.203 | 0.002 |

| ES ← Mun | 0.046 | 0.010 | 4.38 | 0.289 | 0.001 |

| As ← Mun | -0.21 | 0.071 | -3.05 | -0.199 | 0.002 |

| Aam ← Mun | -0.169 | 0.065 | -2.61 | -0.171 | 0.009 |

| ES ← Mc | -0.008 | 0.009 | -0.820 | -0.047 | 0.412 |

| Mun ← Mc | -0.58 | 0.060 | -9.73 | -0.561 | 0.001 |

| Aam ← Mc | 0.13 | 0.058 | 2.25 | 0.127 | 0.024 |

| Mc ← SA | 0.18 | 0.187 | 0.993 | 0.067 | 0.321 |

| Aam ← SA | 0.85 | 0.162 | 5.25 | 0.297 | 0.001 |

| Aav ← SA | 0.74 | 0.169 | 4.41 | 0.239 | 0.001 |

| Mun ← SA | -0.23 | 0.197 | -1.18 | -0.080 | 0.237 |

| ES ← SA | -0.14 | 0.026 | -5.80 | -0.325 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: Aav, avoidant attachment; Aam, ambivalent attachment; As, secure attachment; Mc, mentalization (certainty dimention); Muc, Mentalization (uncertainty dimention); ES, ego strength; SA, social anxiety.

a Arrows represent the relationship direction.

The initial research model demonstrated an acceptable fit; however, four paths within it were found to be non-significant. Subsequently, a revised model, with the non-significant paths removed, was also examined.

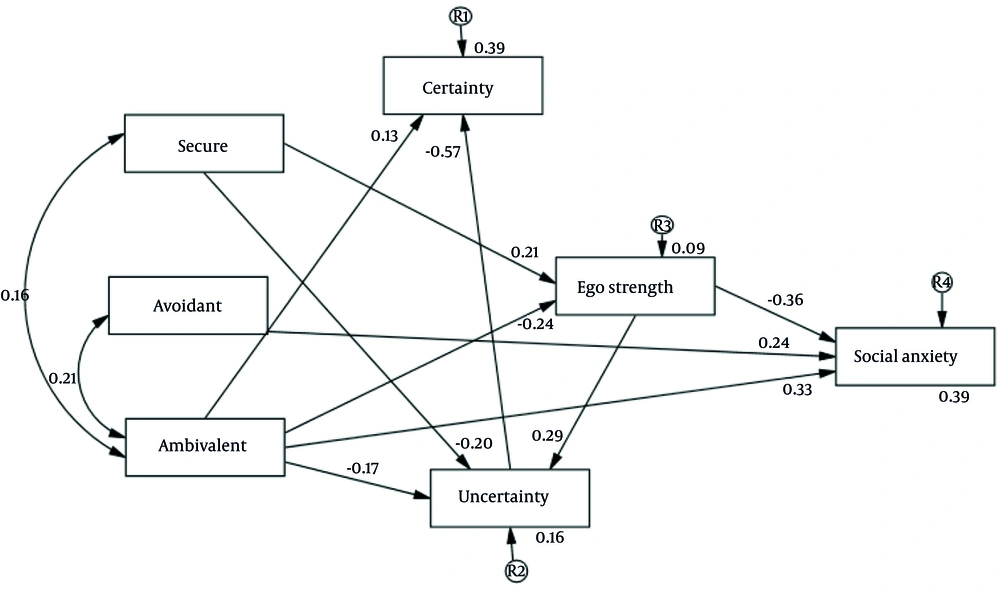

Based on the fitted model (CMIN/DF = 2.15, GFI = 0.975, AGFI = 0.923, CFI = 0.963, RMSEA = 0.074, AIC = 58.60, BIC = 121.19) presented in Figure 2, all estimated path coefficients (relationships between variables) were statistically significant (Table 4). According to the results obtained in this model, 39% of the variance in the certainty dimension, 16% of the variance in the uncertainty dimension, 9% of the variance in ego strength, and finally, 39% of the variance in social anxiety were explained. The strength and direction of the relationship between each of the variables are presented in Table 4.

| Predictor and Dependent Variables a | B | S.E. | C.R. | Standard Coefficient | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aam ← ES | -1.51 | 0.415 | -3.65 | -0.244 | 0.001 |

| As ← ES | 1.46 | 0.463 | 3.15 | 0.210 | 0.002 |

| ES ← Mun | 0.046 | 0.010 | 4.38 | 0.289 | 0.001 |

| As ← Mun | -0.219 | 0.072 | -3.05 | -0.199 | 0.002 |

| Aam ← Mun | -0.169 | 0.065 | -2.61 | -0.172 | 0.009 |

| Aam ← SA | 0.943 | 0.159 | 5.93 | 0.333 | 0.001 |

| Aav ← SA | 0.759 | 0.170 | 4.46 | 0.245 | 0.001 |

| Mun ← Mc | -0.60 | 0.059 | -10.25 | -0.573 | 0.001 |

| Aam ← Mc | 0.138 | 0.057 | 2.40 | 0.134 | 0.016 |

| ES ← SA | -0.164 | 0.025 | -6.54 | -0.359 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: Aav, avoidant attachment; Aam, ambivalent attachment; As, secure attachment; Mc, mentalization (certainty dimention); Muc, Mentalization (uncertainty dimention); ES, ego strength; SA, social anxiety.

a Arrows represent the relationship direction.

Given that the explained variance associated with each variable in the original model (Figure 1 and Table 3) and the modified model (Figure 2 and Table 4) exhibited almost no difference, considering the slightly improved fit indices and the simplicity (parsimony) of the modified model, the latter is deemed more optimal.

5. Discussion

Path analysis was conducted to examine the proposed pathological model of social anxiety, and two closely related structural models were tested. The initial model included all theoretically hypothesized paths, whereas the final model was derived by removing non-significant paths to achieve greater parsimony and theoretical coherence. Although the final model explained slightly less variance in social anxiety compared to the initial model (39% versus 42%), this reduction reflects a model refinement process rather than a loss of explanatory value, emphasizing structural clarity over maximal prediction.

Based on the final path model, the following paths were not significant: Avoidant and secure attachment styles, avoidant attachment style to ego strength, ego strength to mentalization (certainty), mentalization (certainty) to social anxiety, and mentalization (uncertainty) to social anxiety. In contrast, ambivalent and secure attachment styles showed significant associations with ego strength; ego strength and secure and ambivalent attachment styles were significantly related to mentalization (uncertainty); ambivalent and avoidant attachment styles were directly associated with social anxiety; ambivalent attachment style showed a significant relationship with mentalization (certainty); and ego strength demonstrated a significant direct relationship with social anxiety.

Importantly, the removal of non-significant direct paths from mentalization to social anxiety suggests that mentalization does not operate as an independent predictor within the overall structural organization of the model. Rather, its role becomes meaningful when considered within the broader configuration of attachment-related vulnerabilities and ego functioning. In this sense, the present findings support a model-based, theory-driven interpretation of social anxiety, in which attachment styles function as predisposing factors, while ego strength and mentalization capacities are structurally embedded mechanisms contributing to the maintenance and expression of social anxiety symptoms during adolescence.

Previous findings regarding the mediating role of mentalization and ego-related capacities provide an important empirical context for interpreting the present path-analytic model; however, these studies have predominantly relied on variable-centered or regression-based approaches. Derogar et al. (30) concluded in their study that mentalization played a significant mediating role between attachment styles and social anxiety. Similarly, as demonstrated by Hayden et al. (31), mentalization plays a significant mediating role between attachment style and individual distress. Mansouri and Besharat (32) also indicated that ego strength played a mediating role between attachment styles and mindfulness. Additionally, Safari Mousavi et al. (33) stated that insecure attachment style directly, and indirectly through mindfulness, influenced mentalization. In contrast to these studies, the present findings suggest that mentalization does not function as an independent mediator, but rather operates within a broader structural configuration in which attachment styles shape ego strength, and ego strength constitutes the primary pathway linking relational vulnerability to social anxiety.

The initial hypothesized model was refined through path analysis by removing non-significant paths in order to achieve a more parsimonious and theoretically coherent structure. Specifically, direct paths from secure and avoidant attachment styles to social anxiety, as well as direct paths from mentalization certainty and uncertainty to social anxiety were excluded due to lack of statistical significance. This refinement resulted in a final model with improved interpretability, in which attachment styles exert their influence through structurally meaningful indirect pathways. The final model explained a substantial proportion of variance in social anxiety, highlighting the central role of ego strength as a key organizational construct linking attachment-related vulnerabilities to anxiety outcomes. Rather than weakening the model, the elimination of non-significant paths strengthened its theoretical clarity by emphasizing patterned relationships over isolated associations.

In interpreting these findings from a model-focused perspective, it is important to note that while mentalization capacity is associated with social anxiety, its effect is indirect and moderated when considered alongside other variables, particularly attachment styles and ego strength. Specifically, direct paths from the certainty and uncertainty dimensions of mentalization to social anxiety are not significant. This indicates that mentalization does not directly account for variations in social anxiety but exerts its effect indirectly through ego strength.

This aligns with the conceptualization of mentalization as a capacity embedded within ego functioning. Although mentalization may show a significant bivariate association with social anxiety, its effect becomes indirect when integrated within the broader framework of ego functions, represented here as ego strength. In this model, higher ego strength is associated with greater certainty and lower uncertainty in mentalization, highlighting a strong interdependence between these constructs.

Mentalization capacity plays a crucial role in emotion regulation and the development of a cohesive sense of identity. Previous research has consistently shown that this capacity develops within the context of secure attachment-based relationships, particularly when a caregiver is able to perceive the child as a subject with mental states and respond sensitively to their needs. In contrast, insensitivity or lack of responsiveness from caregivers can foster insecure attachment, subsequently creating challenges in the development of mentalization abilities. Empirical studies indicate that parents who cannot empathically reflect on the child’s inner experiences may contribute to hypermentalization, excessive rationalization of mental states, fragmentation of the self, impaired emotion regulation, and reduced capacity for stable, mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships. These early interactions are encoded as internal working models, which serve as cognitive-affective templates of the self, the caregiver, and their relationship, and predict later emotional and social functioning. By enabling reflection on both one’s own and others’ mental states, mentalization forms the foundation for effective social interactions (22, 34-37).

In the Iranian socio-cultural context, families are generally hierarchical, with parents — particularly fathers — exerting a controlling role, while children adopt a more submissive role. Such family structures may increase the likelihood of insecure attachment. In these contexts, the primary caregiver’s ability to understand and mentalize the child’s feelings is further compromised, especially when reflective functioning is weak. Moreover, adolescents, particularly girls, face high social expectations to conform to norms, creating dual pressures to adapt and perform. These cultural expectations can exacerbate fear of negative evaluation, a core component of social anxiety.

Individuals with high attachment anxiety, characterized by negative self-view and fear of interpersonal rejection, are prone to heightened social anxiety in evaluative situations. Conversely, adults with high attachment avoidance are self-critical, intolerant of uncertainty, distrustful of others, and uncomfortable with closeness. Empirical evidence suggests that these distinct attachment orientations predispose individuals to social anxiety through different psychological mechanisms (22, 34-37). Within this framework, mentalization capacity, when considered in the context of overall ego strength, mediates the relationship between attachment styles and social anxiety by shaping emotion regulation in social contexts.

Defense mechanisms are unconscious processes that modulate reactions to emotionally and socially challenging situations (36). Research demonstrates that immature defenses are associated with distortion of self-image and emotional withdrawal, whereas mature defenses enhance awareness of feelings and ideas, leading to resilience and psychological well-being (38-40).

Individuals with high ego strength are better equipped to manage distress, criticism, mistakes, and other challenging situations without defensiveness, learning from these experiences and taking responsibility for their actions. While our findings did not indicate a direct mediating role of ego strength between attachment styles and social anxiety, ego strength is closely linked to mentalization capacity, which has been shown to partially mediate this relationship. Adults with elevated attachment anxiety or avoidance tend to report higher social anxiety, and mentalization partially explains this association. Thus, ego strength indirectly supports social functioning by enabling mentalization, highlighting its importance for overall mental health and adaptive responses to stress, including social anxiety (14).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study have important implications for clinical practice in addressing social anxiety in adolescents. By integrating the results into clinical assessments and interventions, mental health professionals can adopt a model-based approach that considers the interplay between attachment styles, ego strength, and mentalization capacity. Consistent with prior research, insecure attachment and weak parent-adolescent emotional bonds predispose adolescents to immature defense mechanisms and impaired mentalization, which in turn contribute to the development of social anxiety symptoms (22, 34-40).

Specifically, adolescents experiencing social situations may struggle to accurately understand their own and others’ emotions and mental states, heightening vulnerability to anxiety. Assessing these factors in clinical settings allows for targeted interventions aimed at enhancing adaptive functioning. Evidence from previous studies suggests that secure attachment, high mentalization capacity, and strong ego strength are protective against social anxiety (14, 34-36). Accordingly, interventions designed to improve attachment security, mentalization skills, and ego strength — such as attachment-based therapy, mentalization-based therapy, or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) — may effectively alleviate social anxiety symptoms.

From a preventive and educational perspective, the model highlights the importance of assessing parent and adolescent functioning in these domains. Identifying deficits in parental awareness or adolescent development can inform preventive strategies, including parent and school administrator education, targeted skill-building in adolescents, and early interventions to reduce risk for social anxiety. By evaluating adolescents based on model factors, practitioners can determine susceptibility to social anxiety and implement evidence-informed preventive measures to mitigate the emergence of developmental difficulties.

In conclusion, this study offers a comprehensive, model-based understanding of the factors contributing to social anxiety, providing a foundation for both clinical intervention and preventive strategies aimed at promoting adolescent mental health.

5.2. Limitations

The present research is correlational in nature; thus, causal relationships among the variables cannot be inferred, and interventional studies are needed to further explore the relationships among the investigated variables. The statistical population of this research is limited to adolescent students; thus, the results cannot be generalized to all adolescents. Another limitation is that social anxiety is a topic influenced by numerous factors. Due to the extensive length of the questionnaires and potential difficulties in their completion, only the variables of the present study were investigated.