1. Background

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by persistent, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive rituals or mental acts (compulsions) (1). While OCD manifests across diverse symptom presentations, contamination obsessions and washing compulsions demonstrate significantly elevated prevalence rates within Iranian populations, attributed to deeply embedded cultural and religious frameworks that emphasize ritual purity and cleanliness (2). Islamic religious practices, including ablution rituals and purification requirements, combined with traditional Iranian cultural values prioritizing cleanliness, may create heightened salience for contamination-related concerns that can become pathologically amplified in individuals predisposed to OCD (2, 3). This cultural-religious intersection makes washing/contamination subtypes particularly relevant for investigation within Iranian contexts, as normative purification practices may serve as both protective factors and potential vulnerability markers when dysregulated (4).

Adolescence represents a critical period for mental health disorders, with OCD being particularly prominent as approximately 50% of OCD cases emerge before age 18 (5). Adolescent OCD frequently co-occurs with other mental health conditions including anxiety disorders, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and eating disorders, creating complex clinical presentations. This disorder significantly impairs academic performance, social relationships, and family functioning, creating substantial individual and societal burden that extends beyond the primary OCD symptoms (5, 6). Despite this impact, research examining underlying mechanisms in adolescent populations remains limited compared to adult studies.

Emotional processing theory posits that individuals with OCD exhibit heightened threat perception and emotional distress sensitivity, leading to systematic misinterpretation of normative intrusive cognitions as physically dangerous or morally unacceptable (7, 8). This maladaptive cognitive processing generates anxiety that precipitates compulsive neutralization behaviors, which paradoxically maintain the obsessive-compulsive cycle by preventing natural habituation to emotional distress (9). Research demonstrates multiple discrete emotions contribute to OCD pathogenesis, including fear, shame, and disgust (10, 11). Disgust emerges as particularly salient in contamination-focused presentations, representing an adaptive response to potentially harmful stimuli that becomes dysregulated in clinical contexts (12).

During adolescence, limited emotional awareness and immature emotion regulation skills influence individual responses to emotional experiences (13-15). In adolescents and young adults with OCD, anxiety sensitivity (AS) significantly impacts symptom development, persistence, and treatment outcomes (16). Anxiety sensitivity encompasses fear of anxiety-related situations based on beliefs regarding their potential negative consequences (17). Specific AS dimensions relate to distinct OCD features (18). Cognitive concerns about loss of control when experiencing disgust may increase compensatory compulsions, while physiological concerns about disgust-related somatic reactions (nausea, dizziness, fainting) can trigger compulsive behaviors. Social concerns regarding peer acceptance may similarly precipitate compensatory compulsions aimed at reducing these distressing experiences. Cisler et al. (19) demonstrated that individuals with elevated AS who exhibit greater disgust propensity perceive their disgust responses as more unbearable and severe. All three AS factors interact with disgust responsivity to predict contamination fears, with physical concerns demonstrating the strongest predictive relationship.

Repetitive behaviors such as rituals and compulsions often develop in response to distress from unpleasant experiences that individuals have learned to manage over time (20). Distress tolerance (DT) encompasses the ability to withstand negative emotional states without engaging in maladaptive behaviors to escape or avoid these experiences (20, 21). Individuals with higher DT demonstrate greater capacity to tolerate uncomfortable emotions, reducing reliance on compulsive behaviors for emotional relief. This adaptive skill may counteract AS’s disruptive effects by providing alternative regulatory strategies (21). High AS and emotional alexithymia in adolescence with OCD can reduce the individual’s capacity to tolerate distress, which leads to a decrease in the individual’s resistance to performing compulsive behaviors (22, 23). Enhanced DT enables individuals to experience disgust and associated distress without immediate behavioral escape responses. Therefore, DT may serve as a protective factor that mediates the relationship between disgust sensitivity and OCD symptoms.

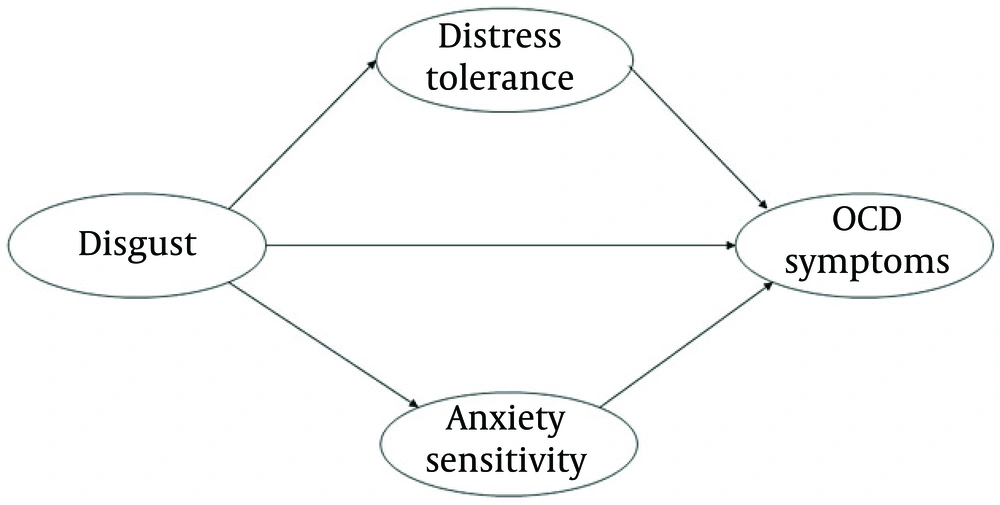

The research model (Figure 1) proposes that disgust sensitivity influences OCD symptom severity both directly and through two mediating pathways: AS and DT. Anxiety sensitivity amplifies the disgust-OCD relationship by intensifying fear of disgust-related sensations, while DT buffers this relationship through adaptive coping mechanisms. The model suggests these mediators simultaneously determine how disgust sensitivity translates into clinical symptom expression.

Examining AS and DT relationships in adolescence is critical given this period’s peak OCD onset, heightened neuroplastic capacity, and unique developmental vulnerabilities. The asynchronous development of these constructs creates windows wherein maladaptive patterns may become entrenched, establishing self-reinforcing cycles predictive of long-term trajectories. Understanding these developmental dynamics informs early identification and mechanistically targeted interventions during optimal neuroplastic periods, potentially preventing symptom consolidation and improving prognosis rather than merely managing manifest symptoms.

2. Objectives

One of the components that can facilitate the treatment process for OCD is understanding the emotions that cause a person’s anxiety and ultimately lead them to perform rituals. The present study aimed to focus on the emotion of disgust as one of the main basic emotions in OCD and examine the mediating factors and individual traits that may be involved in the relationship between disgust and symptom severity.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

This structural equation modeling study employed partial least squares (PLS) methods. Hair et al. (24) recommended a minimum sample size of 100 participants for models containing five or fewer constructs, with each construct measured by more than three indicators having correlation coefficients of 0.6 or higher. The minimum sample size was set at 150 participants, ultimately recruiting 189 adolescents (ages 11 - 18) diagnosed with OCD. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling from Kargarnejad Psychiatric Hospital and other psychotherapy centers in Kashan in 2024, with referrals made by pediatric physicians and clinical psychologists using patient files. Inclusion criteria included informed consent, absence of psychotic disorders, tic disorders, addiction (assessed via semi-structured interview), and major depressive disorder. Exclusion criteria were incomplete questionnaire responses (> 20% unanswered) and expressed dissatisfaction with study participation. Ethical approval was obtained prior to data collection.

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale-Revised

The Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale (DPSS) is an assessment tool used to measure an individual’s tendency to experience disgust (propensity) and the emotional impact of that experience (sensitivity). The first revised version of this scale consists of 16 items, and the psychometric properties of this scale have been investigated in different studies (25). Zanjani et al. (26) demonstrated superior fit for the 13-item, four-factor version over the 16-item scale. This study employed the four-factor structure: Sensitivity to disgust, tendency to experience disgust, avoidance of disgusting stimuli, and sensitivity to disgust outcomes (α = 0.83).

3.2.2. Padua Inventory-Washington State University Revision

The Padua Inventory-Washington State University Revision (PI-WSUR) measures OCD symptom dimensions across 39 items, including harm obsessions/impulses, contamination obsessions and washing compulsions, checking compulsions, and dressing/grooming compulsions. The contamination obsessions and washing compulsions subscale (10 items) assessed washing/contamination OCD symptoms, demonstrating strong psychometric properties (α = 0.92, split-half = 0.95, test-retest r = 0.77) (27).

3.2.3. Anxiety Sensitivity Index

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI) measures fear of anxiety-related emotions and accompanying physiological and cognitive symptoms. Developed by Floyd et al., this 16-item, 5-point Likert scale has been extensively validated (28). Three factors include: Physical concerns (8 items), cognitive control loss (4 items), and social observation (4 items). Iranian adolescent validation demonstrated strong reliability (test-retest = 0.81, α = 0.80, split-half = 0.78) and concurrent validity (r = 0.68 with anxiety measures) (29).

3.2.4. Distress Tolerance Scale

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS) was developed based on established theoretical concepts and measurement instruments (30). Comprehensive psychometric evaluation yielded a 15-item final version with one general factor and four subscales. Caiado et al. reported subscale reliabilities of 0.73 - 0.83 with overall reliability of 0.89 (31). Kianfar et al. (32) confirmed adequate adolescent psychometric properties (total α = 0.85, subscale α > 0.65).

3.3. Data Analysis

Demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, while research variables were examined using means, standard deviations, and correlations via SPSS 22. The study employed PLS structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using Smart PLS 3, selected for superior performance with complex exploratory models and enabling separate evaluation of measurement and structural components.

4. Results

The results of descriptive data analysis on the demographic information showed that the mean and standard deviation of the age of the participants were 14.83 and 2.33 years. The gender frequency and duration of symptoms are shown in Table 1. Fifty-four participants (28.6%) reported a history of psychiatric treatment. Of the 41 participants taking medication, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors — primarily sertraline and fluoxetine — were frequently used most.

| Categories | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Boy | 87 (46) |

| Girl | 102 (54) |

| OCD symptoms duration | |

| < 6 (mo) | 40 (21.2) |

| 6 (mo) - 1 (y) | 41 (21.7) |

| 1 - 2 (y) | 55 (29.1) |

| 2 - 5 (y) | 30 (15.9) |

| > 5 (y) | 23 (12.2) |

| Medication use | |

| No current medication use | 148 (78.3) |

| Current medication use | |

| SSRIs | 22 (11.6) |

| Antipsychotics | 6 (3.1) |

| Benzodiazepines | 7 (3.7) |

| Other psychiatric medications | 9 (4.7) |

Disgust demonstrated significant positive correlations with DT (r = 0.39), AS (r = 0.67), and washing/contamination OCD symptoms (r = 0.79). The strong correlation between disgust and OCD symptoms (r = 0.79) may reflect item-level overlap between measures. Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale-Revised (DPSS-R) items assessing avoidance ("I avoid disgusting things") and physical reactions ("Disgusting things make my stomach turn.") align closely with PI-WSUR contamination items ("I do not use public restrooms", "I have difficulty touching dirty things"). This overlap suggests shared underlying mechanisms between disgust sensitivity and contamination-focused OCD symptoms, though future research should employ measures with greater discriminant validity. OCD symptoms significantly correlated with AS (r = 0.72) but not with DT (Table 2).

Abbreviations: CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; AS, anxiety sensitivity; DT, distress tolerance; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

a P < 0.01.

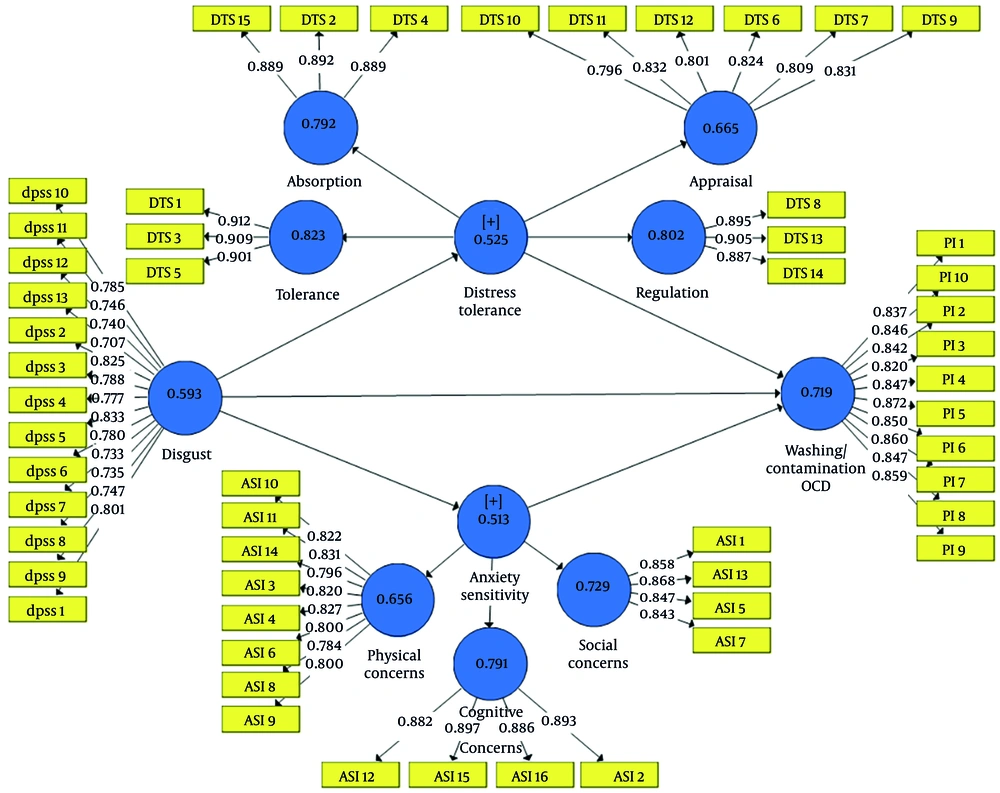

To evaluate the measurement model, reliability and validity of the scale were assessed. To assess reliability, Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) were considered (33). Results in Table 2 show that Cronbach’s alpha and CR values were greater than the minimum required value of 0.7 (33). For validity, convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated. Convergent validity was assessed by outer loadings and average variance extracted (AVE) (33). Outer loadings and AVE were greater than the required minimum value of 0.4 and 0.5 (Figure 2).

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) criterion with a threshold of 0.90 (34). All scales have competent discriminant validity (Table 3). While these values did not exceed the 0.90 criterion, the high correlations between absorption-social concerns (0.882), disgust-W/C OCD (0.837), social concerns-tolerance (0.814), and appraisal-absorption (0.796) indicate that discriminant validity may be compromised for these construct pairs, requiring careful interpretation of the structural model results involving these relationships.

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1- Absorption | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2- Cognitive-concerns | 0.339 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3- Disgust | 0.573 | 0.464 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4- Appraisal | 0.796 | 0.145 | 0.344 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5- Physical-concerns | 0.721 | 0.573 | 0.705 | 0.505 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6- Regulation | 0.602 | 0.062 | 0.154 | 0.771 | 0.283 | - | - | - | - |

| 7- Social-concerns | 0.882 | 0.578 | 0.789 | 0.7 | 0.699 | 0.48 | - | - | - |

| 8- Tolerance | 0.732 | 0.286 | 0.674 | 0.587 | 0.575 | 0.367 | 0.814 | - | - |

| 9- C.W/OCD | 0.479 | 0.614 | 0.837 | 0.183 | 0.665 | 0.068 | 0.72 | 0.465 | - |

Abbreviation: OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The proposed structural model was examined for all the relationships. To evaluate the structural model, beta, t-values, coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2) are assessed (33). Disgust (β = 0.772, P < 0.001) and AS (β = 0.331, P < 0.001) have a positive and significant impact and DT (β = -0.257, P < 0.001) has a negative and significant impact on OCD symptoms (Table 4). The R2 value for washing/contamination OCD symptoms shows that 84.9% of the variance in the severity of OCD symptoms is determined by its predictor variables, such as disgust, AS, and DT. The Q2 criterion is also greater than zero (0.105).

| Relationships | β | Std. Deviation | t-Statistics | P-Values | f2 | R2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disgust → anxiety-sensitivity | 0.726 | 0.037 | 19.44 | > 0.001 | 1.111 | 0.526 | 0.263 |

| Disgust → distress-tolerance | 0.472 | 0.067 | 7.015 | > 0.001 | 0.287 | 0.223 | 0.105 |

| Disgust → W/C OCD | 0.772 | 0.036 | 21.661 | > 0.001 | 1.871 | 0.849 | 0.105 |

| Anxiety-sensitivity → W/C OCD | 0.331 | 0.046 | 7.262 | > 0.001 | 0.270 | - | - |

| Distress-tolerance → W/C OCD | -0.257 | 0.037 | 6.997 | > 0.001 | 0.268 | - | - |

Abbreviation: OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder.

To evaluate indirect effects, a bootstrapping (with 5000 re-samples) procedure bias-corrected with 95% confidence interval was employed. According to Table 5, the mediation hypotheses were confirmed and disgust can predict the washing/contamination OCD symptoms through AS and DT. Although DT did not demonstrate a significant correlation with OCD symptoms (Table 2), it functioned as a significant negative mediator in the relationship between DPSS-R and OCD symptoms. The mediation pathway revealed that DPSS-R positively predicted DT, which then negatively predicted OCD symptoms (Table 4). However, this pattern suggests a maladaptive form of DT. Experiencing frequent disgust may increase individuals’ capacity to tolerate distress, but this tolerance develops through maladaptive coping mechanisms (such as avoidance or compulsive behaviors) that paradoxically contribute to greater OCD symptom severity.

| Specific Indirect Effects | β | Std. Deviation | t-Statistics | P-Values | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disgust → anxiety-sensitivity → W/C OCD | 0.244 | 0.04 | 6.22 | < 0.001 | 0.18 → 0.3 |

| Disgust → distress-tolerance → W/C OCD | -0.123 | 0.029 | 4.16 | < 0.001 | -0.17 → -0.07 |

| Total | - | - | - | - | 5.0% → 95.0% |

The measurement model demonstrates an acceptable fit (χ2 = 48.296, NFI = 0.915, SRMR = 0.09). The NFI values above 0.9 represent acceptable fit. Values less than 0.10 (or 0.08 for SRMR in a more conservative version) are considered a good fit (35).

5. Discussion

This cross-sectional study demonstrates that disgust positively predicts AS, DT, and washing/contamination OCD symptoms, with AS and DT mediating the disgust-OCD relationship. The findings reveal complex pathways wherein disgust influences OCD symptoms through multiple psychological constructs. These results align with empirical research supporting sequential mediation models wherein disgust sensitivity influences OCD symptoms through AS and DT pathways (36, 37).

Consistent with these findings, a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies on emotional processing in OCD demonstrated increased activation in a fronto-limbic circuit, including the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) extending into the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (38). This supports a potential neural basis for the psychological pathways observed. Neuroimaging studies have identified neural circuits involved in processing disgust and OCD (particularly in the insula and ACC), which may also be involved in DT and anxiety (39, 40). The meta-analysis also noted that activation in the insula and putamen was more pronounced in studies with higher rates of comorbidity with anxiety and mood disorders (38).

Developmental trajectories of AS and DT during adolescence create critical vulnerability windows for OCD pathogenesis. Early adolescence presents peak risk as AS emerges amid heightened physiological reactivity and immature prefrontal regulation, establishing optimal conditions for symptom consolidation (41). A developmental asynchrony occurs wherein AS manifests before sophisticated DT capacities, creating a temporal mismatch between intense somatic experiences and limited metacognitive regulation abilities (42). This asynchrony may explain AS’s robust mediating role between disgust sensitivity and OCD symptoms during adolescence.

Persistently elevated AS generates self-perpetuating maladaptive cycles. Early compulsive behaviors and avoidance strategies impede natural DT acquisition by preventing necessary exposure experiences, creating developmental cascades wherein high baseline AS progressively compromises DT capabilities (43). Heightened social evaluation concerns during adolescence further amplify these trajectories (43, 44). Longitudinal evidence demonstrates strengthening AS/DT mediating effects throughout adolescence, particularly during developmental transitions, establishing self-reinforcing patterns wherein early configurations predict increasingly severe symptom trajectories (21, 43, 45). This developmental framework suggests interventions targeting underlying mechanistic vulnerabilities during neuroplastic windows may prove more efficacious than symptom-focused approaches.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, convenience sampling from a single region (Kashan) limits generalizability to broader Iranian adolescent populations, despite the adequate sample size for PLS-SEM analysis. Future research should employ random sampling across multiple regions. Second, while HTMT values generally support discriminant validity, several values approaching 0.9 indicate potential construct overlap. Third, the non-significant DT-OCD correlation may reflect the DTS’s broad construct measurement, which lacks specificity for adolescents. Alternative instruments such as the Emotion Reactivity Scale Body and Emotional Awareness Questionnaire should be considered in future research. Focusing exclusively on washing symptoms suggests future studies should recruit participants specifically diagnosed with contamination-related OCD and incorporate clinical observation methods for direct symptom assessment. Finally, excluding family accommodation measures represents a significant oversight, as family involvement critically influences adolescent OCD behaviors. Future research should incorporate the Family Accommodation Scale and Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale to examine how family responses moderate study relationships. Additionally, longitudinal designs are necessary for establishing causal relationships between variables.