1. Background

Alcohol consumption and its effects on mental health have been a subject of considerable interest and concern among researchers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers (1). Among the myriad mental health disorders, panic disorder stands out as a condition characterized by sudden and recurrent episodes of intense fear and discomfort, often accompanied by physical symptoms such as palpitations, sweating, and shortness of breath (2). Alcohol use, whether in moderation or excess, has long been intertwined with the fabric of American society. Excessive or problematic drinking patterns can lead to a wide array of adverse consequences, including alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and various mental health issues (3). Panic disorder, on the other hand, is a debilitating mental health condition that can severely impact an individual’s quality of life, often co-occurring with other psychiatric disorders (4). Prior research has demonstrated a complex bidirectional association between alcohol use and panic disorder (5). A significant proportion of individuals with panic disorder also meet the criteria for AUD (6, 7), and both alcohol intake and withdrawal have been implicated in the precipitation of panic attacks (8).

2. Objectives

The present literature is increasingly interested in the complex relationship between alcohol use and panic disorder. However, the strength of the association between alcohol use and panic disorder remains inconclusive, even among individuals diagnosed with AUD according to DSM-V criteria, and is particularly unclear among those who consume alcohol without necessarily meeting diagnostic criteria for the disorder. This cross-sectional study seeks to evaluate the connection between alcohol consumption and panic disorder among US adults by thoroughly examining the interactions between alcohol use and panic disorder. The present study aims to shed light on the prevalence of panic disorder among people who drink alcohol in different ways by using nationally representative data. It also aims to clarify the sociodemographic traits, comorbidities, and potential risk factors connected to this complicated interaction. Clarifying this relationship has important implications for clinical practice and public health, aiding in identifying at-risk individuals and supporting the development of targeted interventions and policies to reduce alcohol-related mental health burdens.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

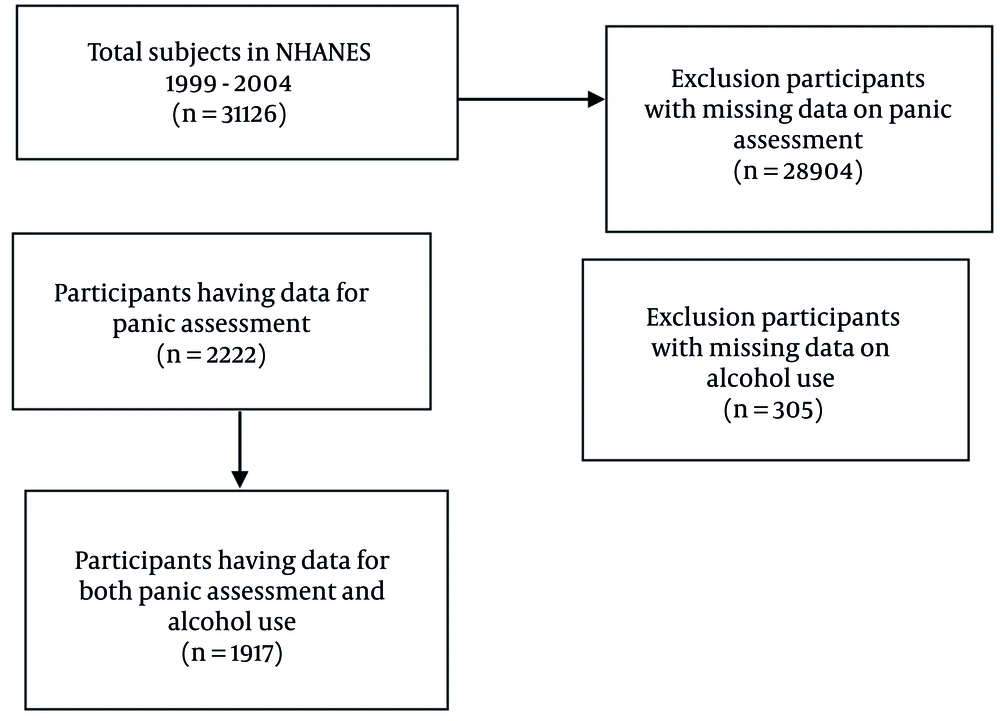

This study aims to investigate the association between alcohol and panic among US adults using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The NHANES is a cross-sectional survey that gathers detailed information on nutrition and health from a sample of the American population. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board approved the NHANES procedure, including data collection and definitions. Participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the survey and, in exchange, received payment and a report on the medical findings of the study. Adults who took part in the NHANES 1999 - 2004 evaluation made up the study sample.

3.2. Data Collection

The first three cycles of NHANES data (1999 - 2004) were utilized since the panic disorder assessment was performed only in these cycles. The evaluation consisted of various examination elements, including lab testing, and medical, dental, and physiological assessments. These examinations were carried out by competent medical professionals using current technology to ensure accurate and high-quality data gathering. To ensure participant privacy and confidentiality, the NHANES dataset used in this study was de-identified by the NCHS, with personally identifiable information removed and masked variance units applied to prevent re-identification. All NHANES participants provided written informed consent, as approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, prior to data collection. Our study adhered to NCHS guidelines by using only publicly available, anonymized data from the 1999 - 2004 cycles, and analyses were conducted in secure environments to maintain confidentiality.

3.3. Variables Definition

During the face-to-face segment of the Mobile Examination Center (MEC) interview in the NHANES study, participants were subjected to a modified version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1 (CIDI-Auto 2.1). The CIDI is a comprehensive and standardized interview tool utilized for the assessment of mental disorders and the provision of diagnoses in accordance with the criteria outlined in the tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10, World Health Organization 1992, 1993), as well as the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV, 1994). Its adaptability for use in large-scale epidemiological studies, its suitability for administration by non-specialist interviewers, its independence from external informants or medical records, and its ability to evaluate historical as well as current disorders make the CIDI a valuable instrument for both clinical and research purposes. The NHANES CIDI, designed as a computer-administered version, included three diagnostic modules focusing on conditions within the past 12 months, namely panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and depressive disorders. For the purpose of this study, we used four questions to develop our dependent variables: (1) Ever panic: “In your entire lifetime, have you ever had an attack of fear or panic when all of a sudden you felt frightened, anxious, or uneasy?”; (2) sudden panic: “Ever attack for no reason, out of the blue?”; (3) one year panic: “Have you had an attack like this in the past 12 months?”; and (4) panic: Panic disorder diagnosis using all available scores from respondents. For assessing alcohol abuse, the question, "Ever have 5 or more drinks every day?" was asked of NHANES participants.

Relevant rationale and previously published research served as a guide for the selection of covariates. We collected demographic information on the respondents’ age, gender, racial and ethnic origin, level of education, marital status, yearly family income, drinking, and smoking habits using standardized questionnaires. Demographic factors such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and income have been shown to influence the prevalence and patterns of alcohol use as well as the risk of anxiety disorders, including panic disorder, based on previous assessments (9, 10). Therefore, these factors were included as covariates. Also, smoking habit, which has been linked to both panic attacks/disorder and alcohol use, was included as a covariate, in addition to the well-established association between smoking and alcohol consumption (11-13). Groups were created for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Hispanic, and other racial/ethnic people. There were two levels of education: A diploma or above and less than a high school diploma. For marital status, there were two options: Married/having a partner or single. Smoking history was divided into past and present smokers based on their responses to questions regarding whether or not they had ever smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lives and whether or not they were now smoking. Alcohol consumption status was determined based on the answer to the question, "Have you consumed at least 12 alcoholic drinks in a year?" Past medical problems were identified based on responses to the medical condition questionnaire, and each disease required a prior diagnosis from a clinician.

3.4. Analysis

We conducted data analyses using Stata Corp (2017) (Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). We calculated the entire set of data a six-year sample weight in order to guarantee the representativeness of our findings using the given formula in NHANES analytical guidelines (if sddsrvyr in (1,2) then MEC6YR = 2/3 * WTMEC4YR; /* for 1999-2002 */ else if sddsrvyr = 3 then MEC6YR = 1/3 * WTMEC2YR; /* for 2003-2004 */). Multivariate and univariate logistic regression was used to investigate the relationship between alcohol and panic. For continuous data, such as age, we used the Wilcoxon rank-sum test; for categorical data, we used the chi-square test; and for the outcomes, we used weighted percentages. To account for the complex survey design, we employed the full sample two-year MEC exam weight, the masked variance pseudo-PSU for clustering, and the masked variance pseudo-stratum for stratification. Results with a P-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

This study encompassed an analysis of data from a total of 2,222 patients (Figure 1), with baseline characteristics revealing that individuals diagnosed with panic disorder exhibited a higher propensity to be female, single, possess higher educational status and income level, be non-smokers, engage in less physical activity, and consume lower levels of alcohol. A summary of these baseline characteristics can be found in Table 1. The results of our univariate analysis, provided in Table 2, unveiled a statistically significant association between alcohol consumption and an elevated odds ratio (OR) for both panic disorder [OR = 2.19, 95% CI (1.04, 4.60)] and the occurrence of sudden panic attacks [OR = 2.31, 95% CI (1.15, 4.62)]. Furthermore, individuals who smoke exhibited a considerably greater risk of developing panic disorder compared to non-smokers [OR = 4.3, 95% CI (2.03, 9.51)]. Smoking also correlated with a significantly increased risk of experiencing sudden panic attacks [OR = 1.65, 95% CI (1.06, 2.56)] and a history of at least one previous panic attack [OR = 1.49, 95% CI (1.13, 1.98)]. Conversely, no statistically significant impact on our outcomes was identified for the other covariates examined.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 980 (49.1) |

| Female | 1242 (50.9) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1003 (68.15) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 440 (12.86) |

| Mexican American | 682 (18.99) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/living with partner | 1247 (56.88) |

| Single | 904 (43.12) |

| Education (y) | |

| Less than 12 | 561 (18.1) |

| More than 12 | 1658 (81.9) |

| Income | |

| Below poverty | 425 (16.36) |

| Above poverty | 1622 (83.64) |

| Drinking status | |

| Yes | 278 (15.51) |

| No | 1639 (84.49) |

| Smoking status | |

| Yes | 906 (44.43) |

| No | 1315 (55.57) |

| Physical activity | |

| Yes | 577 (26.1) |

| No | 1632 (73.9) |

| Variables | Panic | Sudden Panic | Ever Panic | One Year Panic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | OR | 95% CI | P-Value | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Male | 0.51 | (0.26 - 0.97) | 0.042 a | 0.57 | (0.36 - 0.90) | 0.019 a | 0.81 | (0.65 - 1.00) | 0.060 | 0.55 | (0.37 - 0.82) | 0.004 a |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| NH white | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| NH black | 0.84 | (0.36 - 1.95) | 0.686 | 0.94 | (0.46 - 1.89) | 0.864 | 0.80 | (0.64 - 1.01) | 0.069 | 0.88 | (0.56 - 1.37) | 0.566 |

| Mexican-American | 0.82 | (0.32 - 2.06) | 0.670 | 0.82 | (0.51 - 1.32) | 0.415 | 0.50 | (0.39 - 0.65) | 0.000 a | 1.29 | (0.81 - 2.05) | 0.266 |

| Education (y) | ||||||||||||

| Less than 12 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| More than 12 | 0.87 | (0.46 - 1.66) | 0.686 | 0.79 | (0.49 - 1.26) | 0.318 | 0.97 | (0.72 - 1.30) | 0.842 | 0.94 | (0.61 - 1.45) | 0.800 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Single | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Married | 0.43 | (0.23 - 0.80) | 0.009 a | 1.09 | (0.71 - 1.68) | 0.666 | 0.94 | (0.75 - 1.18) | 0.643 | 0.81 | (0.55 - 1.18) | 0.281 |

| Income | ||||||||||||

| Below poverty | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Above poverty | 0.41 | (0.21 - 0.80) | 0.010 | 0.79 | (0.46 - 1.35) | 0.384 | 0.86 | (0.65 - 1.15) | 0.328 | 0.62 | (0.36 - 1.06) | 0.081 |

| Drinking status | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.19 | (1.04 - 4.60) | 0.038 | 2.31 | (1.15 - 4.62) | 0.019 | 1.44 | (0.99 - 2.11) | 0.055 | 1.18 | (0.72 - 1.91) | 0.488 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Yes | 4.3 | (2.03 - 9.51) | 0.000 | 1.65 | (1.06 - 2.56) | 0.027 | 1.49 | (1.13 - 1.98) | 0.006 | 1.31 | (0.93 - 1.83) | 0.109 |

| Physical activity | ||||||||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Yes | 0.82 | (0.33 - 2.01) | 0.662 | 1.08 | (0.61 - 1.93) | 0.771 | 1.14 | (0.85 - 1.53) | 0.338 | 0.71 | (0.44 - 1.15) | 0.168 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

a A P-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Following adjustment for potential confounding factors via multivariable logistic regression analysis, our findings underscored a robust association between alcohol consumption and both panic disorder [OR = 2.60, 95% CI (1.10, 6.11)] and the incidence of sudden panic attacks [OR = 3.07, 95% CI (1.50, 6.26)]. However, our results did not support a statistically significant influence of alcohol consumption on patients’ lifetime history of panic attacks or on occurrences of panic attacks within the past year. The findings are presented in Table 3.

| Outcomes | OR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panic | 2.60 | [1.10, 6.11] | 0.029 |

| Sudden panic | 3.07 | [1.50, 6.26] | 0.003 |

| Ever panic | 1.42 | [0.92, 2.19] | 0.101 |

| One year panic | 1.37 | [0.74, 2.51] | 0.298 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

5. Discussion

We utilized the opportunity to analyze the NHANES database to explore the relationship between alcohol consumption and panic disorder. Our investigation revealed a significant positive correlation between alcohol consumption and panic disorder. Moreover, we observed a significant positive relationship between alcohol consumption and sudden panic attacks in participants. However, the link between alcohol consumption and experiencing at least one panic attack within the last year was not significant. We also evaluated the correlation between alcohol consumption and experiencing at least one panic attack throughout life, which was also non-significant. These findings are based on our adjusted analysis controlling for other factors associated with panic disorder, including gender, race, education, income, BMI, physical activity, etc.

The relationship between panic disorder and alcohol consumption has been studied extensively in several investigations. Swendsen et al.’s analysis based on four databases in 1998 indicated that both lifetime alcohol dependence and previous 12-month alcohol dependence were significantly correlated with panic disorder in subjects (14). Another investigation by Burns and Teesson based on the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being, found an OR of 3.9 (95% CI = 2.3 to 6.7) regarding the association between alcohol abuse/dependence and panic disorder (15). Moreover, an analysis of 3,258 participants in Alberta, Canada revealed an OR of 3.1 for panic disorder in patients with alcohol abuse/dependence (16). The lifetime risk of panic disorder in the context of alcohol abuse/dependence was also evaluated according to the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey results, which showed an OR of 2.2 (95% CI = 1.1 to 14.3) (17). Another study by Chou also found a significant association between current panic disorder and alcohol abuse/dependence; however, this association became non-significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons (18).

Accordingly, our study is in agreement with most previous investigations in terms of the relationship between alcohol use and panic disorder. However, our OR was relatively smaller compared to previous studies, likely due to our focus on participants who merely use alcohol rather than those diagnosed with alcohol abuse/dependence. By examining a broader population of alcohol users rather than restricting the analysis to individuals with diagnosed alcohol abuse or dependence, our findings offer insights that are more generalizable to the wider population affected by this association. Moreover, this approach avoids bias introduced by the specific characteristics and severe comorbidities commonly associated with AUD, making the results more relevant to clinical practice and public health. It also aids in the earlier identification of at-risk individuals and guides the development of targeted interventions and policies for a larger segment of the population. We performed our adjusted analysis controlling for several other factors associated with panic disorders, such as smoking, which may further decrease our OR. Overall, our study provides more valuable insights into the real-life context of alcohol consumption and panic disorder compared to previous studies, which were mainly focused on participants with a diagnosis of alcohol disorders.

Several studies utilizing the NHANES database have investigated the psychiatric comorbidities associated with substance abuse. However, most of these studies did not specifically examine the relationship between alcohol use and panic attacks or panic disorder (19). Grant et al. conducted a study that explored the association between alcohol consumption and panic disorder, both with and without agoraphobia. Their findings demonstrated that AUD was significantly associated with an increased risk of developing panic disorder. Moreover, their analysis revealed that the comorbidity of agoraphobia and panic disorder was associated with alcohol use to a greater extent than merely panic disorder. Furthermore, they suggested that panic disorder with agoraphobia may represent a more severe subtype of the disorder (9). In a more recent study by Grant et al., employing DSM-V criteria, the OR for panic disorder in the context of AUD was found to be lower than previously reported, with an OR of 1.1 to 1.4 (20).

The ORs of a diagnosis of alcohol abuse/dependence in subjects with panic disorder within the last year are not constant among different surveys (14, 21-24). We also found a non-significant association between alcohol use and panic disorder within the last year. Therefore, we encourage further research in this regard. Several studies have investigated the potential genetic link between alcohol use and panic disorder. Research has shown that subjects with a family history of panic disorder are more prone to develop alcohol disorders compared to those without such a history. This suggests a familial connection between the two disorders (25). In relation to this matter, Nurrnberger et al. conducted an analysis on a substantial sample of 9,950 participants and reported a relative risk of 1.9 after adjusting for various factors (26). Additionally, Torvik et al. suggested that the link between alcohol use and panic disorder can be explained by shared genetic links, suggesting a lack of causality relationship (27). These findings may provide insight into the relationship between alcohol use and panic disorder.

The order of occurrence of panic disorder and alcohol disorders is also studied. It is suggested that alcohol disorders that come after panic disorder can be considered a form of auto-medication, while alcohol disorders that follow panic disorder are probably due to increased sensitivity to CO2 resulting from alcohol use (2, 28). Alcohol use disrupts several neurobiological systems that may underlie the link between alcohol use and panic disorder. Long-term consumption leads to downregulation of GABA receptors, reducing inhibitory signaling and increasing neural excitability, particularly during withdrawal (29, 30). At the same time, alcohol alters key neurotransmitters involved in anxiety, including serotonin and norepinephrine, and disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which regulates the stress response (31-33). These changes can heighten vulnerability to anxiety and panic (2). Alcohol withdrawal often mimics panic attacks, producing symptoms such as palpitations, tremors, and hyperventilation, which may be misinterpreted as spontaneous panic, especially among individuals with panic disorder who show heightened interoceptive sensitivity and a tendency to catastrophize bodily sensations (34-36). This overlap can reinforce a vicious cycle of anxiety and alcohol use, contributing to the persistence of both conditions.

Our study is strengthened by adjusting several factors in our analysis, which led to more reliable findings. However, this study faced several limitations. As a cross-sectional study, our research is limited in its ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships between panic disorder and alcohol use. Moreover, our incapability to monitor changes in either alcohol use or panic disorder over a period of time restricts our comprehension of the potential interplay and development of these two conditions. In addition, our study relies on self-reported data from participants regarding their experiences with panic attacks, including experiencing panic attacks within the past year, ever, or sudden onset attacks. The subjective nature of these reports may introduce bias into our findings. Therefore, it is important to approach the interpretation of these results with caution. To address these issues, future research using longitudinal designs would be valuable in clarifying causal relationships. Additionally, integrating qualitative or mixed-methods approaches may help capture more nuanced experiences and contextual factors that influence this relationship.

The implications of our findings are significant for both psychiatric and public health contexts. Clinicians can use the yielded results to identify individuals at risk for panic disorder and provide early measures through counseling, therapy, and medication. In the public health context, policies aimed at reducing alcohol consumption, particularly among vulnerable populations with a personal or familial history of panic disorder, can be reconsidered by these findings. Besides these, our results may be beneficial for future strategic planning in relation to reducing the burden of alcohol use comorbidities. For instance, it may be advisable to assess individuals with alcohol use for a history of panic attacks/disorder to facilitate early diagnosis and intervention. Additionally, patients who consume alcohol should be informed about the potential increased risk of developing panic disorder. Overall, our findings highlight the importance of addressing alcohol use and panic disorder in order to promote mental health and well-being.

To conclude, we indicated that alcohol use is significantly associated with panic disorder and sudden panic attacks. Moreover, we provided more attributable findings to real-life contexts regarding alcohol use and panic disorder as one of its destructive comorbidities. These findings suggest that individuals with a history of panic attacks should exercise caution when consuming alcohol to avoid triggering panic attacks. Further research, particularly longitudinal studies, is needed to explore the causal relationship between alcohol use and panic disorder, as well as the underlying mechanisms of this association and to develop effective interventions for subjects at risk.