1. Background

The quality of parent-child interactions forms a cornerstone of healthy child development (1). The widespread adoption of smartphones has fundamentally altered family dynamics, raising significant concerns about their impact on crucial parent-child relationships (2). The phenomenon of "phubbing" — a portmanteau of "phone" and "snubbing" that describes the act of ignoring others while using a smartphone — has emerged as a particular concern within family contexts (3). While phubbing occurs across various settings, including workplaces (4), family environments (5), and social gatherings (6), its prevalence within parent-child interactions warrants special attention due to the formative nature of these relationships.

Attachment theory provides a valuable framework for understanding why parental phubbing might be particularly detrimental to child development. This theory, pioneered by Bowlby (7) and expanded by Ainsworth (8), posits that the quality and consistency of early caregiving relationships form the foundation for children's emotional regulation, social competence, and behavioral patterns. Secure attachment develops when caregivers are consistently available, responsive, and sensitive to children's needs — qualities that may be compromised when parents are frequently engaged with their smartphones (9).

Research has shown that smartphone interruptions significantly reduce parental sensitivity during interactions with young children (10). This reduced sensitivity can lead children to develop insecure attachment patterns, potentially manifesting as anxious, avoidant, or disorganized attachment styles (7, 11). Consequently, children may develop behavioral problems as they struggle with feelings of rejection or emotional unavailability from their caregivers (12-15).

Behavioral problems include externalizing behaviors [aggression, rule-breaking (RB)] and internalizing behaviors (anxiety, depression) (13, 16, 17). These challenges are more common in families with socioeconomic or mental health stressors (2, 18) and can persist into adolescence and adulthood, affecting mental health and social adjustment (19, 20).

Parent-child relationship quality serves as both a protective factor and a mechanism linking parenting behaviors to child outcomes (5, 21). When these relationships lack warmth and responsiveness, children are more likely to develop behavioral difficulties (11).

Relationship quality involves warmth, communication, trust, and support (5, 22). It buffers stress and mediates the impact of parenting on child behavior (23). Studies indicate that problematic smartphone use reduces parent-child relationship quality (2, 24, 25). Parental phubbing is associated with diminished responsiveness and emotional availability (26).

Attachment theory posits that disrupted attunement from smartphone use compromises children’s security (13). Family systems theory highlights that boundary ambiguity strains relationships (27). Collectively, evidence supports that parent-child relationship quality mediates the phubbing-behavior link (5, 21).

1.1. Cultural Context of Iran

Iranian families emphasize strong intergenerational bonds and collectivist values (28). These cultural traits shape family interactions and may influence how children perceive parental phubbing. With smartphone penetration reaching 69% in 2021 (29, 30), Iranian families navigate a tension between traditional values and modern technology. Because cultural norms shape the experience and effects of phubbing (6, 31, 32), findings from Western contexts may not fully generalize to Iran.

1.2. Research Gaps and Present Study

The existing literature on parental smartphone uses and child outcomes presents two significant gaps that our study addresses. First, while previous research has established direct correlations between parental phubbing and children's behavioral problems (25, 26), few studies have examined the specific mechanisms underlying this relationship (12, 13). In particular, the mediating role of parent-child relationship quality remains underexplored (5, 21). Second, despite the growing body of international research on phubbing, this phenomenon has not been adequately investigated within Iranian families. Cultural factors unique to Iran — including traditional family structures, communication norms, and technology adoption patterns — may influence both smartphones use patterns and parent-child dynamics (33).

2. Objectives

This study therefore aims to investigate the relationship between parental phubbing (independent variable) and children's behavioral problems (dependent variable), with specific attention to the mediating role of parent-child relationship quality.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted between November and December 2024 using online questionnaires. The target population comprised parents with at least one child between 6- and 12-years old residing in Mazandaran province, northern Iran. Inclusion criteria specified that participants must be a primary caregiver of the child, able to read Persian, and have regular access to digital devices.

3.2. Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

The sample size was calculated using Stata software based on previous studies examining similar relationships, with parameters set at 5% type I error and 80% power. This analysis indicated a minimum requirement of 304 participants to detect medium effect sizes (detailed power analysis parameters are provided in the Appendix 1). To account for potential incomplete responses, we aimed to recruit approximately 400 participants.

Convenience sampling was employed through school networks in Mazandaran province. Questionnaire links were distributed to school principals via common virtual networking platforms in Iran (Eitaa, WhatsApp, and Telegram), who then shared these links with parents through their established virtual groups. Recruitment continued until the required sample size was achieved. The overall response rate was 60%, with 405 complete responses retained for analysis (of the 674 participants in the online questionnaire, only 405 submitted their responses).

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committees of Islamic Azad University (approval code: IR.IAU.AMOL.REC.1403.1386). At the beginning of the online questionnaire, participants were provided with information about the study purpose and procedures. They were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous, with no personally identifying information collected. Digital consent was obtained before participants could proceed to the questionnaire items. Data were stored on secure, password-protected servers with access restricted to the research team.

3.4. Measures

3.4.1. Parental Phubbing

The Persian version of the General Phubbing Scale was used to measure parental phubbing behaviors (34). This 15-item scale was adapted from Chotpitayasunondh's General Phubbing Scale (35) and validated for use in Iranian populations. Responses are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater phubbing behavior. The scale comprises four subscales, including "Nomophobia" (4 items), "Conflict" (4 items), "Self-isolation" (4 items), and "Problem Acknowledgement" (3 items). In the current study, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was 0.85 for the total scale, with subscale reliabilities of 0.70 [nomophobia (NP)], 0.77 [interpersonal conflict (IC)], 0.85 [self-isolation (SI)], and 0.45 [problem acknowledgement (PA)].

3.4.2. Children's Behavioral Problems

Children's behavioral problems were assessed using selected subscales from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) school-age version (6 - 18 years) - Parent Report Form. These subscales included "Anxiety/Depression" (AD) with 14 items, "Withdrawal/Depression" (WD) with 8 items, "Rule-Breaking Behavior" (RB) with 17 items, and "Aggressive Behavior" (AG) with 19 items.

These specific subscales were selected to represent both internalizing (AD, WD) and externalizing (RB, AG) behavioral problems most relevant to the research questions. Items are rated on a 3-point scale where 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true. Higher scores indicate greater behavioral problems.

The Persian version of this tool was previously standardized in Iran (36, 37). In the current sample, internal Cronbach's alpha was 0.86 for all combined subscales (0.87 for "Aggressive Behavior", 0.57 for "Rule-Breaking Behavior", 0.56 for "Withdrawal/Depression", and 0.74 for “Anxiety/Depression”).

3.4.3. Parent-Child Relationship Quality

The short version of Pianta's Parent-Child Relationship Scale was used to assess relationship quality (22, 38). This 15-item instrument measures two key dimensions of the parent-child relationship, including "Conflict" (8 items) and "Closeness" (7 items). Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To calculate the total score, conflict items are reverse-scored, with higher total scores indicating more favorable parent-child relationships.

The psychometric properties of this scale have been previously established for Iranian populations (39, 40) in studies of parents with children aged 3 - 7 years. For the current sample with children aged 6 - 12 years, internal consistency reliability was 0.85 for the total scale, 0.76 for the conflict subscale, and 0.81 for the closeness subscale.

3.4.4. Demographic Characteristics

Demographic data were collected through self-report items at the beginning of the survey, including parent's gender, parent's education level, child's gender, and number of children.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA version 17.0. Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics, assessment of internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha), and bivariate correlations among study variables. To test the hypothesized mediation model, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed. The measurement model was evaluated first to confirm adequate fit of the latent constructs, followed by testing of the structural model. Model fit was assessed using multiple indices: Chi-square test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Mediation effects were tested using bootstrap procedures with 500 resamples to generate 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

A total of 405 parents completed the survey (response rate: 60%). Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants. The sample consisted predominantly of mothers (87.4%), with most participants having completed university education (62.5%). Most families had only one child (58.0%).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Parent gender | |

| Female (mothers) | 354 (87.4) |

| Male (fathers) | 51 (12.6) |

| Parent education level | |

| High school or less | 152 (37.5) |

| Bachelor's degree | 179 (44.2) |

| Master | 64 (15.8) |

| PhD and more | 10 (2.5) |

| Number of children | |

| One | 235 (58.0) |

| Two | 146 (36.1) |

| Three and more | 24 (5.9) |

| Child gender | |

| Only boy | 99 (24.5) |

| Only girl | 156 (38.6) |

| Both boy and girl | 149 (36.9) |

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the main study variables. Parents reported moderate levels of phubbing (33.92 ± 8.28), with the highest scores observed in the NP subscale (10.80 ± 3.01). Parent-child relationship quality was generally positive (57.23 ± 7.88), with balanced scores on the closeness subscale (28.40 ± 3.98) compared to the conflict subscale (28.83 ± 5.03, reverse-scored for the total). Children's behavioral problems were relatively low across all subscales. Phubbing was negatively correlated with parent-child relationship quality (R = -0.32, P < 0.001) and positively correlated with children's behavioral problems (R = 0.24, P < 0.001). Parent-child relationship quality was strongly negatively correlated with children's behavioral problems (R = -0.57, P < 0.001).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental phubbing (total) | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NP | 0.77 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| IC | 0.86 b | 0.54 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SI | 0.80 b | 0.43 b | 0.69 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PA | 0.71 b | 0.39 b | 0.51 b | 0.45 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Parent-child relationship (total) | -0.32 b | -0.21 b | -0.28 b | -0.32 b | -0.26 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Closeness | -0.22 b | -0.15 | -0.20 b | -0.25 b | -0.15 a | 0.84 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Conflict | -0.33 b | -0.22 b | -0.28 b | -0.30 b | -0.29 b | 0.90 b | 0.52 b | 1 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Behavioral problems (total) | 0.24 b | 0.14 a | 0.19 b | 0.26 b | 0.22 b | -0.57 b | -0.34 b | -0.63 b | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| AD | 0.16 a | 0.08 | 0.13 a | 0.15 a | 0.15 a | -0.38 b | -0.21 b | -0.44 b | 0.79 b | 1 | - | - | - |

| WD | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.07 | -0.32 b | -0.17 a | -0.36 b | 0.56 b | 0.52 b | 1 | - | - |

| RB | 0.24 b | 0.17 b | 0.16 a | 0.24 b | 0.23 b | -0.43 b | -0.27 b | -0.47 b | 0.74 b | 0.37 b | 0.24 b | 1 | - |

| AG | 0.24 b | 0.13 a | 0.19 b | 0.27 b | 0.21 b | -0.56 b | -0.35 b | -0.60 b | 0.90 b | 0.52 b | 0.29 b | 0.67 b | 1 |

| Mean ± SD | 33.92 ± 8.28 | 10.80 ± 3.01 | 7.34 ± 2.85 | 6.66 ± 2.66 | 5.49 ± 1.77 | 57.23 ± 7.88 | 28.40 ± 3.98 | 28.83 ± 5.03 | 21.45 ± 12.64 | 6.00 ± 4.33 | 3.12 ± 2.19 | 2.96 ± 2.68 | 9.37 ± 6.69 |

| Min - max | 17 - 72 | 4 - 20 | 4 - 20 | 4 - 20 | 2 - 10 | 33 - 75 | 7 - 35 | 16 - 40 | 0 - 66 | 0 - 23 | 0 - 13 | 0 - 13 | 0 - 35 |

| Skewness | 0.54 | 0.09 | 0.78 | 1.12 | 0.08 | -0.25 | -0.74 | -0.23 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.04 |

| Kurtosis | 3.43 | 2.78 | 3.48 | 4.51 | 2.62 | 2.93 | 4.95 | 2.68 | 3.89 | 4.21 | 5.12 | 4.18 | 3.87 |

Abbreviations: NP, nomophobia; IC, interpersonal conflict; SI, self-isolation; AD, anxiety/depression; WD, withdrawal/depression; RB, rule-breaking behavior; AG, aggressive behavior.

a P < 0.01.

b P < 0.001.

4.2. Measurement Models

Prior to testing the structural model, we evaluated the measurement models for each construct. Table 3 presents the fit indices for all measurement models. All models demonstrated acceptable to good fit according to conventional criteria.

| Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA (90% CI) | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental phubbing | 159.54 | 71 | 2.24 | 0.05 (0.04, 0.06) | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Parent-child relationship | 247.27 | 87 | 2.84 | 0.07 (0.06, 0.08) | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.06 |

| Children's behavioral problems | 413.35 | 113 | 3.65 | 0.07 (0.06, 0.08) | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.06 |

Abbreviations: RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

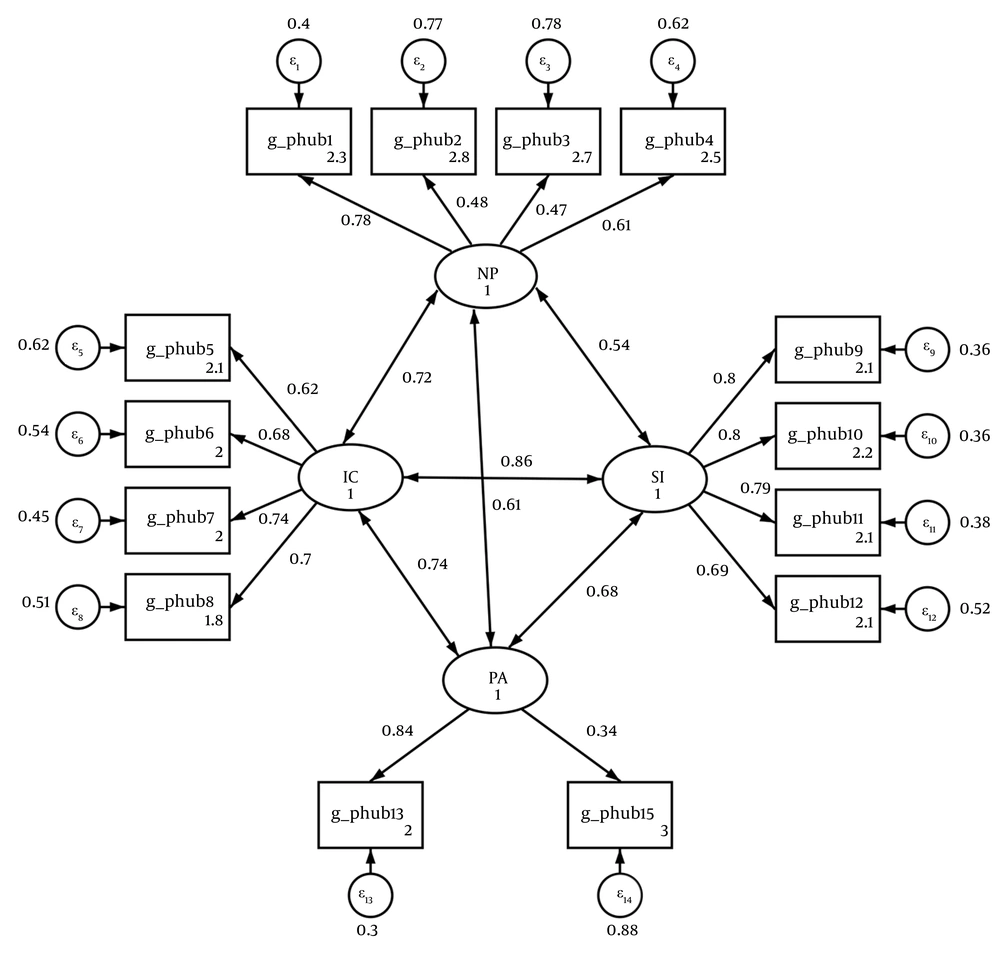

For the parental phubbing construct, a four-factor model was confirmed with the domains of NP, IC, SI, and PA. Factor loadings ranged from 0.34 to 0.84, with all loadings statistically significant (P < 0.001, Figure 1).

The measurement model of Generic Scale of Phubbing in parents of children 6 to 12 years; Goodness of Fit indices were χ2(71) = 159.54, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.96, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.94, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.04 (abbreviations: NP, nomophobia; IC, interpersonal conflict; SI, self-isolation; PA, problem acknowledgement).

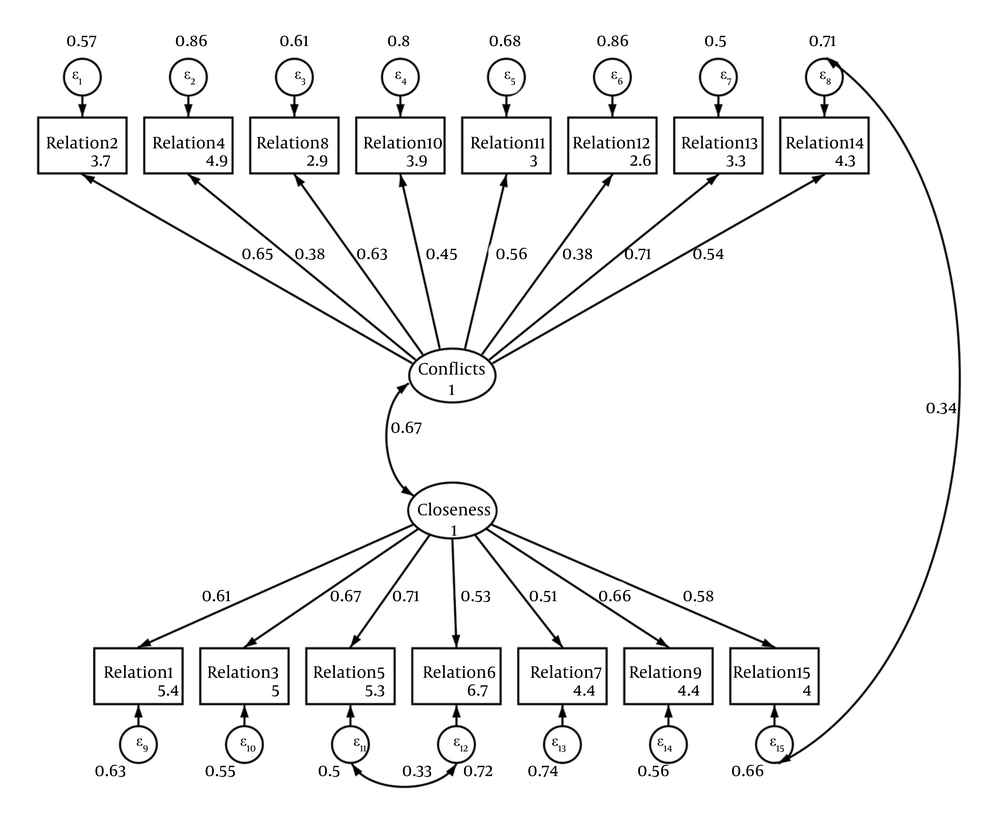

The parent-child relationship scale demonstrated a two-factor structure with closeness and conflict subscales. All factor loadings were statistically significant (P < 0.001), ranging from 0.51 to 0.71 for closeness items and 0.38 to 0.71 for conflict items (Figure 2).

The measurement model of Child-Parent Relationship Scale in parents of children 6 to 12 years; Goodness of Fit indices were χ2(87) = 247.27, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.91, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.89, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.06.

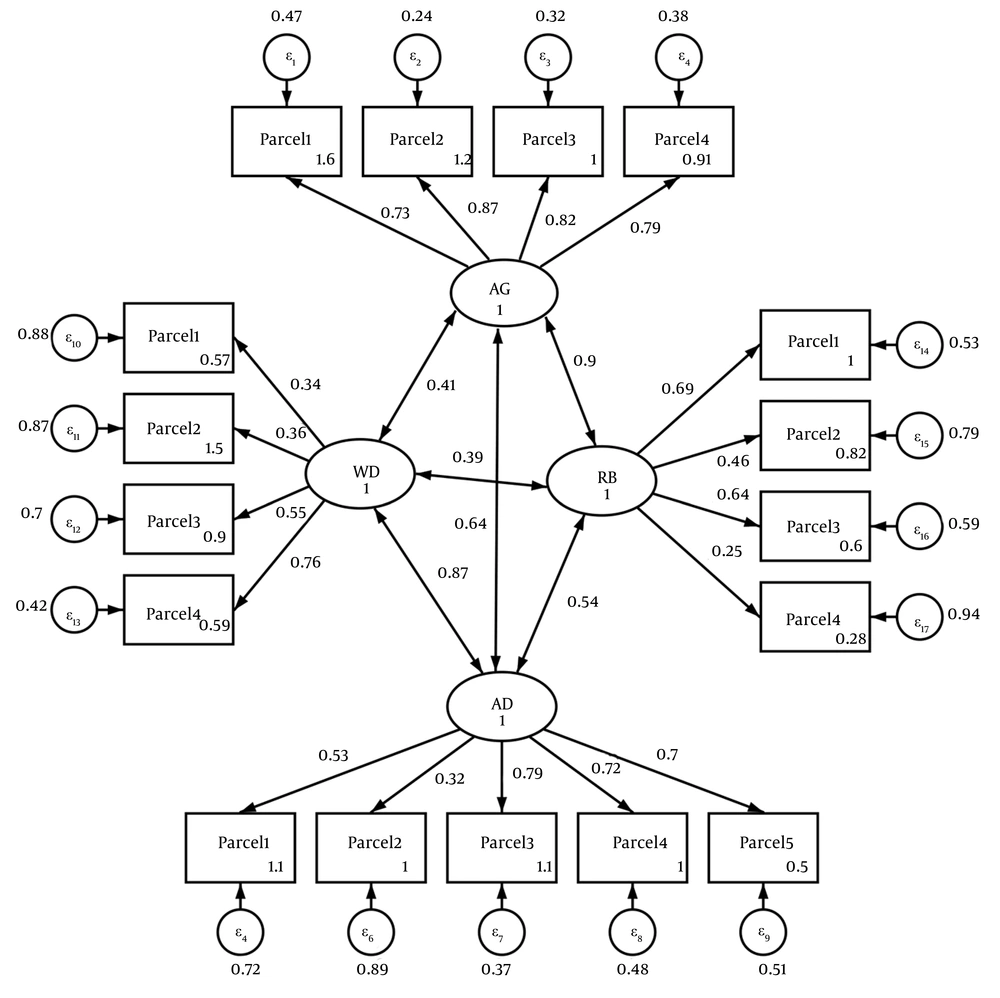

For children's behavioral problems, a four-factor model corresponding to the selected CBCL subscales showed acceptable fit. Factor loadings were all significant (P < 0.001), ranging from 0.25 to 0.87 across the four subscales. We used item parceling to reduce the number of questions and improve the fit of the model (41) for each of the domains of children's behavioral problems (Figure 3).

The measurement model of psychosocial problems of children; Goodness of Fit indices were χ2(113) = 413.35, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.89, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.87, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.06 (abbreviations: AG, aggressive behaviour; RB, rule-breaking behaviour; WD, withdrawal/depression; AD, anxious/depressed).

4.3. Structural Model and Mediation Analysis

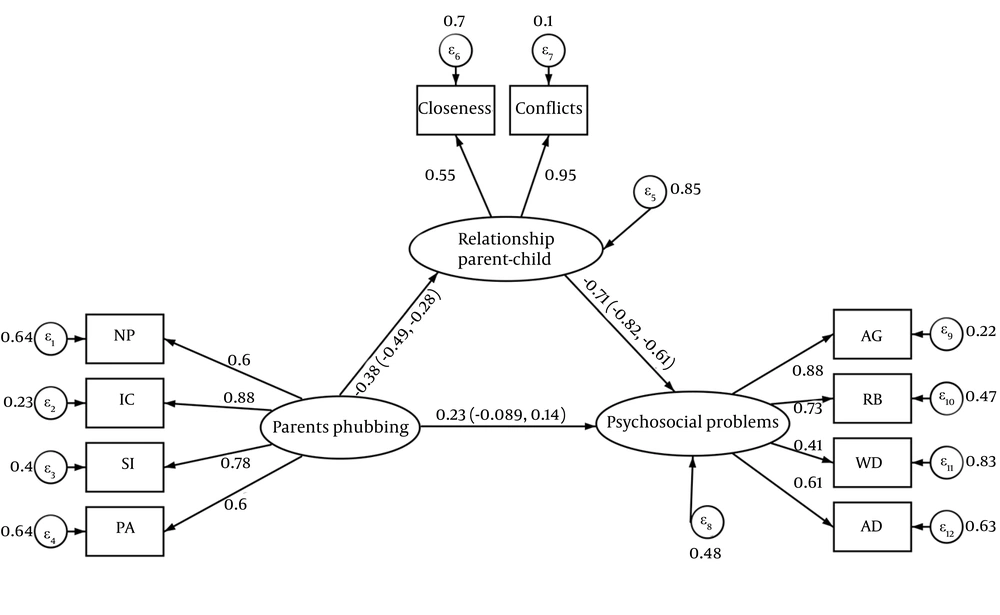

After establishing adequate fit of the measurement models, we tested the hypothesized structural model to examine the direct and indirect relationships between parental phubbing, parent-child relationship quality, and children's behavioral problems. Figure 4 presents the structural model with standardized path coefficients. The structural model demonstrated good fit to the data: χ2(32) = 129.83, P < 0.001; χ2/df = 4.04; RMSEA = 0.08 (90% CI: 0.07, 0.10); CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.91; SRMR = 0.05.

Structural model with standardized path coefficients; Goodness of Fit indices were χ2(32) = 129.83, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.08, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.93, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.91, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.05 (abbreviations: NP, nomophobia; IC, interpersonal conflict; SI, self-isolation; PA, problem acknowledgement; AG, aggressive behaviour; RB, rule-breaking behaviour; WD, withdrawal/depression; AD, anxious/depressed).

Table 4 presents the direct, indirect, and total effects for the hypothesized mediation model. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 4, parental phubbing had a significant negative relationship with parent-child relationship quality (β = -0.38, P < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of parental phubbing were associated with poorer parent-child relationships. Parent-child relationship quality had a significant negative relationship with children's behavioral problems (β = -0.71, P < 0.001), indicating that better parent-child relationships were associated with fewer behavioral problems. The direct effect of parental phubbing on children's behavioral problems was not statistically significant (β = 0.07, P = 0.168). However, the indirect effect through parent-child relationship quality was significant [β = 0.27, 95% CI (0.19, 0.36)], supporting full mediation. The total effect of parental phubbing on children's behavioral problems was significant (β = 0.29, P < 0.001). The model explained 14.7% of the variance in parent-child relationship quality (R2 = 0.147) and 52.3% of the variance in children's behavioral problems (R2 = 0.523). These results support the hypothesized mediation model, indicating that parental phubbing contributes to children's behavioral problems indirectly through its negative impact on parent-child relationship quality.

a Values are expressed as 95% confidence interval (CI) based on 500 bootstrap replications.

b P < 0.001.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between parental phubbing and children's behavioral problems in an Iranian cultural context, with a specific focus on the mediating role of parent-child relationship quality. The findings revealed that parental phubbing significantly predicted children's behavioral problems, and this relationship was fully mediated by parent-child relationship quality. These results contribute to the growing body of literature on the impacts of digital distraction on family dynamics and child development.

Our SEM analysis demonstrated that parental phubbing had a significant negative association with parent-child relationship quality, which in turn had a significant negative association with children's behavioral problems. The non-significant direct effect of parental phubbing on children's behavioral problems, coupled with the significant indirect effect through parent-child relationship quality, supports a full mediation model. These findings suggest that the negative impact of parental phubbing on children's behavioral outcomes operates primarily through its detrimental effect on the quality of parent-child relationships rather than through direct mechanisms.

This pattern of results aligns with previous research. Lv et al. found that mother phubbing was negatively associated with mother-child attachment (β = -0.18, P < 0.001) and positively linked to children's emotional and behavioral problems (β = 0.13, P < 0.001) (12). Similarly, Shi et al. reported that parents phubbing was a significant negative predictor of closeness in the child-parent relationship (β = -0.042, t = -2.565, P < 0.01), while closeness in the child-parent relationship was a significant predictor of children’s prosocial behavior (β = 0.712, t = 51.494, P < 0.05) (25). Also, previous studies showed that adolescents who reported higher parental phubbing directly and indirectly experienced higher severity of depression (26, 42) and smartphone addiction (43, 44).

Our results can be interpreted within both attachment theory (8) and family systems theory (45) frameworks. From an attachment theory perspective, parental phubbing may disrupt the attunement and responsiveness necessary for secure attachment formation. When parents are frequently distracted by smartphones during interactions with their children, they may miss important emotional cues and opportunities for connection, leading to children feeling dismissed or unimportant (9). This disruption to the attachment relationship can manifest in various behavioral problems as children struggle to regulate their emotions and behaviors effectively. From a family systems perspective, parental phubbing introduces a boundary ambiguity within the family system, where technology intrudes upon parent-child interactions. This intrusion can create communication patterns characterized by disconnection and reduced emotional availability, affecting the entire family system's functioning (46). Our findings support this theoretical understanding by demonstrating the centrality of relationship quality in the pathway from parental phubbing to children's outcomes.

The findings from our Iranian sample contribute to the cross-cultural understanding of parental phubbing effects. Despite Iran's traditional emphasis on strong intergenerational bonds and family harmony (28), the negative impact of parental phubbing on parent-child relationships and child outcomes remains significant. This suggests that the detrimental effects of technological intrusion on family relationships may transcend specific cultural contexts, although the manifestations and interpretations of these effects may vary.

Our results parallel findings from various cultural contexts. For example, Xie and Xie found similar pathways from parental phubbing to adolescent depression through parental warmth and rejection in Chinese adolescents (26). Or, Liu et al. showed that parent-child conflict partially mediates the relation between parental phubbing and children’s electronic media use, accounting for 57.72% of the total effect (13). Similarly, Binti et al. demonstrated in Malaysia that mother phubbing was negatively correlated with mother-child relationship quality (R = -0.500, P < 0.001) and positively correlated with children's mobile phone addiction (R = 0.502, P < 0.001) (44). The convergence of findings across these diverse cultural settings suggests a universal vulnerability of parent-child relationships to digital disruptions, despite varying cultural attitudes toward family hierarchy and communication. However, the strength and specific nature of this relationship may differ depending on underlying cultural norms.

Although the present study was conducted in northern Iran — a predominantly collectivist cultural context — it is important to consider how broader cultural factors regarding technology use, family structure, and parenting values may shape the generalizability of these findings. For example, in collectivist societies such as Iran (28) or China (13, 26), family cohesion, interpersonal harmony, and respect for parental authority are highly valued, and disruptions to parent–child communication (such as parental phubbing) may be more keenly felt and lead to more pronounced externalizing or relational problems. Conversely, in more individualistic cultures, where autonomy and independence are prioritized, parental phubbing may be linked more strongly to internalizing symptoms such as loneliness or emotional withdrawal (9, 10). Furthermore, cross-cultural research reveals that parenting styles — and the effects of parental phubbing — are themselves shaped by prevailing cultural attitudes: For instance, authoritarian styles are more common in collectivist contexts, and the consequences of parental phubbing may be moderated by how much cultures value obedience and family connectedness (28). Thus, while the association observed in this study is likely to be present across cultures, variations in family structure, parenting style, and cultural values related to technology use may influence the magnitude and expression of these effects, underscoring the need for culturally sensitive interpretations and future cross-cultural comparisons.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that parental phubbing contributes to children's behavioral problems indirectly through its detrimental impact on the quality of the parent-child relationship. Importantly, the full mediation effect observed suggests that phubbing itself may not be inherently toxic to child behavior unless it compromises the core parent-child bond. Our construct of relationship quality, encompassing both closeness and conflict dimensions, underscores that it is the disruption of this fundamental relationship that serves as the critical buffer influencing child outcomes.

These results emphasize the need for focused interventions that help parents maintain meaningful connections with their children despite the ubiquity of smartphones and other digital devices. Specifically, our findings suggest that psychoeducation programs for parents should highlight the direct impact of phubbing on the parent-child relationship quality, rather than solely addressing general smartphone addiction. Interventions promoting "device-free times" — such as during family meals or playtime — could be particularly effective in fostering closeness and reducing conflict, thereby mitigating behavioral problems in children. Additionally, parenting programs should integrate modules on mindful technology use, distinguishing it from mere screen time limits, to encourage intentional engagement with children. By prioritizing relationship quality, families may be able to mitigate the potential negative effects of technology on children's behavioral outcomes. As smartphone use continues to permeate daily life across cultures, understanding and addressing its impacts on family relationships becomes increasingly crucial for supporting healthy child development.

5.2. Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences. We suggest that longitudinal or experimental designs (e.g., interventions to reduce phubbing) are required to establish temporal precedence and causality. Second, the reliance on self-reported data — particularly from parents — raises concerns about social desirability and recall bias. Parents might underreport their phubbing behaviors or children's behavioral problems. Future studies should incorporate multiple informants (e.g., children, teachers) and observational measures to provide a more comprehensive assessment of these constructs. Third, the sample was predominantly composed of mothers (87.4%) and highly educated parents (62.5%), which may limit generalizability and our ability to examine potential differences in the effects of maternal versus paternal phubbing. Given that fathers and mothers may play different roles in child socialization within Iranian culture, future research should aim for more balanced parental gender representation. Fourth, some of the subscales in our measures showed relatively low reliability coefficients, particularly the PA subscale of the General Phubbing Scale (α = 0.45) and the RB (α = 0.57) and WD (α = 0.56) subscales of the CBCL. Although we acknowledged these limitations in our analyses, they may have attenuated the observed relationships among variables.