1. Background

The rapid proliferation of smartphones has profoundly transformed communication, information access, and daily life activities worldwide. While these devices offer considerable benefits, their excessive or maladaptive use has given rise to emerging behavioral concerns, including nomophobia — defined as the fear or anxiety of being without a mobile phone or beyond mobile phone connectivity (1). Nomophobia differs from smartphone addiction, which broadly encompasses compulsive overuse and dependence on smartphones for various activities, such as gaming or social media. Nomophobia specifically involves anxiety triggered by disconnection from mobile networks or device inaccessibility, reflecting a distinct psychological response to the loss of connectivity (2). In Iran, high smartphone penetration rates (over 70% among young adults) and widespread social media use, despite occasional censorship, contribute to nomophobia’s prevalence, particularly among university students who rely on smartphones for social and academic connectivity (3). Nomophobia is increasingly recognized as a psychological condition with potential detrimental effects on mental health and well-being, particularly among young adults and university students who constitute the highest proportion of smartphone users (2).

Nursing students represent a unique population due to the rigorous academic demands and clinical responsibilities they face, which require optimal cognitive functioning, effective communication skills, and stress management abilities (4). The limited research on nomophobia in nursing students may stem from an underestimation of how their unique stressors amplify smartphone dependency, necessitating targeted investigation (5). The pervasive use of smartphones within this group raises questions about the impact of nomophobia on critical aspects of their health and professional competencies. Previous studies have suggested that problematic smartphone use correlates with poor sleep quality, increased stress levels, and impaired social interactions among university students (6). However, conflicting findings on nomophobia-sleep correlations, potentially due to varying methodologies or unaccounted confounders like mental health, highlight the need for further exploration (7).

Sleep quality is vital for cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and overall health, especially for nursing students who must maintain high alertness during clinical rotations (8). Likewise, communication skills are fundamental for nursing practice, affecting patient care outcomes and interprofessional collaboration (9). Elevated stress levels, common among nursing students, can further exacerbate physical and psychological health problems and compromise academic success (10). Understanding the relationships between nomophobia and these key variables could provide valuable insights for designing targeted interventions to support nursing students’ well-being and professional development.

Despite the growing body of literature on smartphone addiction and its consequences among university populations, there is a paucity of research specifically examining nomophobia in nursing students (5, 11), particularly its association with sleep quality, communication skills, and stress levels. Most existing studies focus broadly on general smartphone use or addiction without isolating nomophobia as a distinct phenomenon (12, 13), and few address how it may uniquely affect nursing students’ academic and clinical performance (11). This gap underscores the need for focused research to elucidate these relationships and inform tailored interventions that promote healthier technology use and enhance nursing students’ overall functioning. Additionally, unlike prior research focusing on singular correlates of smartphone addiction, our comprehensive approach elucidates the interplay of these psychosocial factors.

This study is grounded in the stress-coping model, which posits that individuals respond to stressors through coping strategies that can be adaptive or maladaptive (14). This framework provides a rationale for examining how stress and poor sleep quality contribute to nomophobia, while positive communication attitudes may serve as an adaptive coping resource.

We hypothesized that, within the stress-coping model, nomophobia is positively correlated with stress and sleep disturbances due to maladaptive coping, with positive communication attitudes acting as an adaptive coping mechanism to mitigate nomophobia’s impact.

2. Objectives

This study aims to investigate the prevalence of nomophobia and examine its association with sleep quality, communication skills, and perceived stress among nursing students. By identifying potential correlations, the findings may contribute to enhanced awareness and inform strategies to mitigate the adverse effects of smartphone dependency in this vulnerable population.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Study Design

cross-sectional, correlational study was conducted between March and May 2025 among undergraduate nursing students enrolled at the Islamic Azad University of Kashan and Kashan University of Medical Sciences. A total of 208 students participated, meeting the inclusion criteria of being currently engaged in clinical training and owning a personal smartphone. Students on academic leave or with diagnosed psychiatric disorders were excluded. Stratified sampling ensured proportional representation from different academic years. Stratified sampling was used to ensure proportional representation across academic years (first to fourth year). The sampling frame consisted of all eligible students at both universities, divided into four strata based on academic year. Proportional allocation was applied based on the enrollment size of each year, and participants were randomly selected within each stratum using a random number generator to minimize selection bias. Participants with diagnosed psychiatric disorders were identified through self-reporting on the demographic questionnaire and, where available, verified via university health records. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

3.2. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was determined using G*Power version 3.1 for multiple regression analysis, assuming a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), an alpha of 0.05, power of 0.95, and 8 predictors. This calculation indicated a minimum of 160 participants. To enhance statistical power and account for potential incomplete data, we targeted a sample of at least 200 students, ultimately enrolling 208 participants. A post-hoc power analysis based on the observed effect size (R2 = 0.426 from the full regression model) confirmed an achieved power of 0.97, indicating a sufficient sample size to detect significant effects.

3.3. Measures

A demographic questionnaire was administered to capture information on age, gender, marital status, academic year, average daily smartphone use, and monthly internet usage. Nomophobia was measured using the Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) developed by Yildirim and Correia, consisting of 20 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (15). The Persian version, validated in a prior Iranian study (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) (16), demonstrated high internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Sleep quality was assessed via the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which evaluates sleep disturbances, latency, duration, and subjective quality over the preceding month. The PSQI global score ranges from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality (17). The validity and reliability of the Persian version of PSQI have previously been evaluated in an Iranian population, showing acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) and high sensitivity (94%) for a cutoff score of 5 (18). In this study, the PSQI showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.80).

Communication skills attitudes were measured using the Communication Skills Attitude Scale (CSAS), comprising Positive Attitude Scale (PAS) and Negative Attitude Scale (NAS) subscales. The CSAS contains 26 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Scores for positive and negative subscales are calculated separately by summing the respective item scores, with higher scores indicating stronger positive or negative attitudes. In some studies, negative subscale items are reverse-scored so that higher overall scores consistently reflect a more favorable attitude (19). The validity and reliability of the Persian version of CSAS have previously been evaluated in an Iranian population, showing good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.84), high reproducibility (ICC = 0.81), and excellent content validity (S-CVI/Ave = 0.94) (20). In the current sample, internal consistency was strong for CSAS-PAS (Cronbach’s α = 0.87) and acceptable for CSAS-NAS (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Perceived stress in clinical settings was measured with the Stress Index in Nursing Students (SNSI), a 43-item self-report measure covering academic, clinical, and personal stressors. Higher scores represent greater perceived stress (21). The validity and reliability of the Persian version of SNSI have previously been evaluated in an Iranian population, showing good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.863), high test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.881), and acceptable content validity (S-CVI = 0.88) (22). In this study, the SINS demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.89).

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data collection was conducted between March and May 2025 during scheduled class and clinical training sessions. After obtaining ethical approval from the institutional review boards of both participating universities, faculty coordinators facilitated access to eligible students. Researchers visited classrooms and clinical sites to provide verbal and written explanations of the study aims, procedures, confidentiality measures, and voluntary participation. During the consent process, researchers confirmed eligibility by reviewing inclusion and exclusion criteria with participants, including verifying the absence of diagnosed psychiatric disorders as reported on the demographic questionnaire. Questionnaires were anonymous to encourage honest responses and minimize social desirability bias. Students who provided informed consent completed the paper-based questionnaires in a supervised setting to minimize missing data and ensure independent responses. The average completion time was approximately 20 - 25 minutes. Completed questionnaires were reviewed on-site for completeness, and any missing responses were clarified immediately with the participant to avoid data loss.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

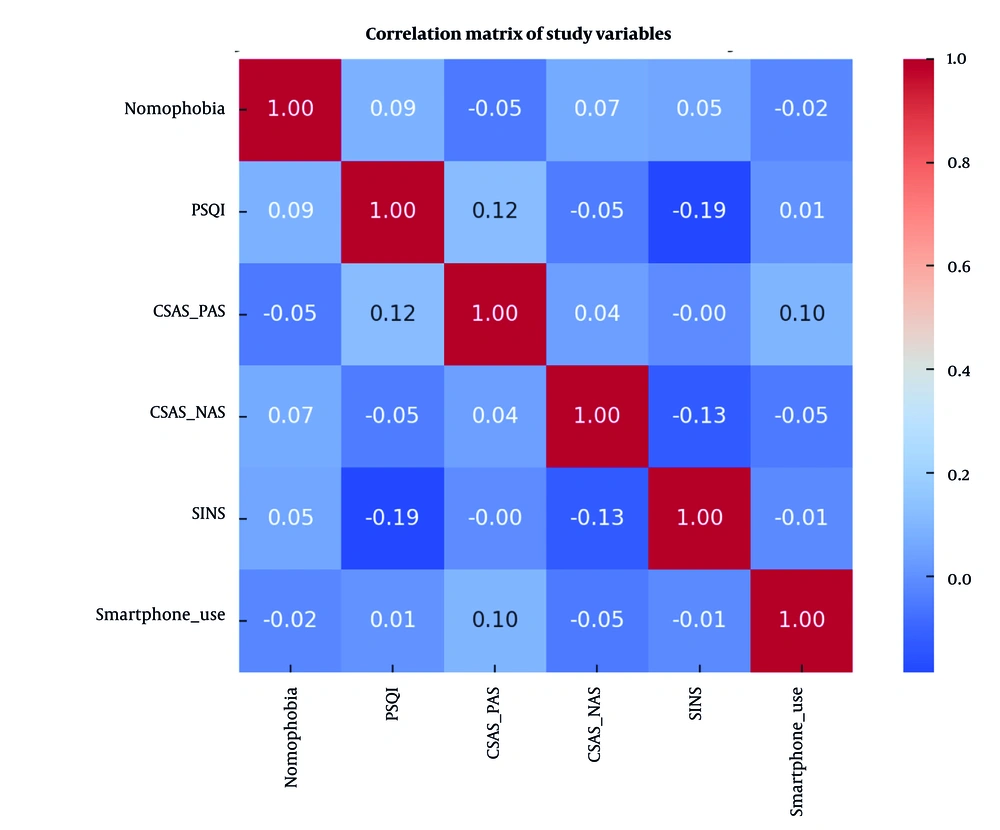

Data were analyzed using R (version 4.3.2) and SPSS (version 29.0). Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, and normality was assessed via Shapiro-Wilk tests and Q-Q plots. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine bivariate relationships between nomophobia and study variables (Figure 1).

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine the unique contributions of sleep quality, communication skills attitudes, and perceived stress to nomophobia after controlling for demographic covariates (age, gender, academic year, daily smartphone use). In step 1, demographic variables were entered; in step 2, PSQI, CSAS-PAS, CSAS-NAS, and SINS scores were entered. Variance inflation factor (VIF) values were calculated to assess multicollinearity, with all values below 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity.

To further quantify the strength of evidence, Bayesian regression analysis was performed using a Jeffreys-Zellner-Siow (JZS) prior for the regression coefficients. Evidence was expressed using Bayes factors (BF10), with BF10 > 3 interpreted as moderate evidence and >10 as strong evidence. Posterior distributions were sampled using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods with 10,000 iterations per chain. Sensitivity analyses compared the JZS prior with a g-prior Bayesian model to assess robustness, yielding consistent posterior means and Bayes factors across both priors, confirming the stability of the findings.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 208 undergraduate nursing students completed the study, with no dropouts, as all enrolled participants provided complete and usable questionnaire responses. The demographic characteristics of the 208 participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 21.48 ± 1.84 years, with the majority being female (67.3%, n = 140) and single (92.3%, n = 192). Students were relatively evenly distributed across academic years, with the largest proportion in the third year (26.4%). The reported mean ± standard deviation daily smartphone usage was high, averaging 5.58 ± 2.27 hours, while mean monthly internet consumption reached 62.4 ± 21.5 GB, indicating substantial technology engagement among participants. Preliminary analyses revealed that female students and those with longer daily smartphone use tended to have higher nomophobia scores, suggesting potential demographic influences to be explored in regression models.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 21.48 ± 1.84 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 140 (67.3) |

| Male | 68 (32.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 192 (92.3) |

| Married | 16 (7.7) |

| Academic (y) | |

| First | 53 (25.5) |

| Second | 50 (24.0) |

| Third | 55 (26.4) |

| Fourth | 50 (24.0) |

| Daily smartphone use (h) | 5.58 ± 2.27 |

| Monthly internet usage (GB) | 62.4 ± 21.5 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

4.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics for all main study variables are summarized in Table 2. Mean NMP-Q scores indicated moderate-to-high levels of nomophobia within the sample. Average PSQI scores exceeded the clinical cutoff (> 5), reflecting generally poor sleep quality. Stress levels (SINS) were also elevated, while CSAS-PAS scores suggested generally positive attitudes toward communication training, though a subset of students scored high on CSAS-NAS, indicating some resistance to formal communication instruction.

Abbreviations: NMP-Q, Nomophobia Questionnaire; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; CSAS, Communication Skills Attitude Scale; PAS, Positive Attitude Scale; NAS, Negative Attitude Scale; SINS, Stress Index in Nursing Students.

a P < 0.001.

b P < 0.05.

c P < 0.01.

Bivariate Pearson correlation analysis revealed several meaningful relationships (Figure 1). Nomophobia was moderately and positively correlated with poorer sleep quality (R = 0.42, P < 0.001) and higher stress (R = 0.51, P < 0.001). Negative correlations emerged with positive communication attitudes (R = −0.26, P < 0.001), suggesting that students with stronger resistance to communication training may be more prone to nomophobia. No significant relationship was observed between negative communication attitudes (CSAS-NAS) and nomophobia after adjusting for multiple comparisons. The observed correlation patterns support the conceptual link between psychosocial well-being and problematic mobile phone dependency.

4.3. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Hierarchical regression results are presented in Table 3. In the first step, demographic variables — age, gender, academic year, and daily smartphone use — explained 11.8% of the variance in nomophobia scores [F (4,203) = 6.79, P < 0.001]. Notably, daily smartphone use was a significant predictor at this stage, indicating that higher usage times were associated with greater nomophobia.

| Predictors | β (Frequentist) | SE | t | P | VIF | Posterior Mean (β) | 95% Credible Interval | Posterior Probability (β > 0 or < 0) | Bayes Factor (BF10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Demographics | |||||||||

| Age | -0.08 | 0.11 | -0.72 | 0.472 | 1.12 | -0.05 | [-0.17, 0.07] | 0.32 | 1.2 |

| Gender (male) | -0.12 | 1.85 | -0.64 | 0.524 | 1.08 | -0.10 | [-0.27, 0.07] | 0.11 | 1.0 |

| Academic year | 0.14 | 0.64 | 1.76 | 0.080 | 1.15 | 0.12 | [0.00, 0.24] | 0.97 | 6.3 |

| Daily smartphone use | 0.21 | 0.32 | 2.91 | 0.004 | 1.20 | 0.15 | [0.03, 0.27] | 0.98 | 9.1 |

| Step 2: Psychosocial variables | |||||||||

| PSQI | 0.28 | 0.43 | 4.85 | < 0.001 | 1.45 | 0.27 | [0.15, 0.39] | 0.99 | 45.7 |

| CSAS-PAS | -0.16 | 0.07 | -2.49 | 0.014 | 1.32 | -0.14 | [-0.26, -0.02] | 0.98 | 20.3 |

| CSAS-NAS | 0.09 | 0.09 | 1.38 | 0.170 | 1.28 | 0.08 | [-0.04, 0.20] | 0.84 | 2.1 |

| SINS | 0.39 | 0.06 | 6.33 | < 0.001 | 1.50 | 0.38 | [0.26, 0.50] | 0.998 | 102.3 |

Abbreviations: VIF, variance inflation factor; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; CSAS, Communication Skills Attitude Scale; PAS, Positive Attitude Scale; NAS, Negative Attitude Scale; SINS, Stress Index in Nursing Students.

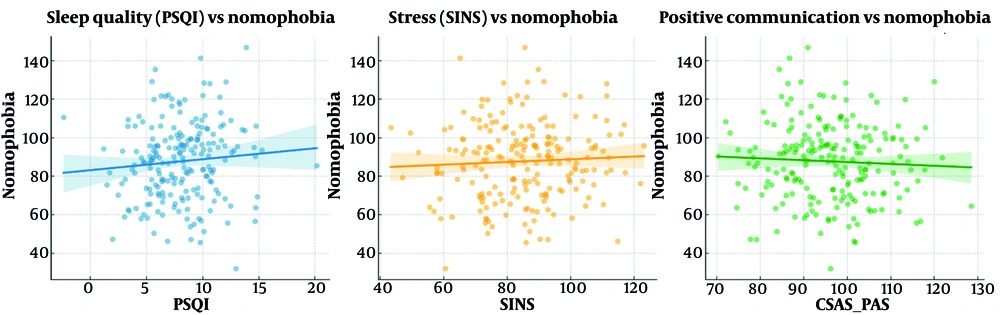

When sleep quality, communication attitudes, and perceived stress were added in Step 2, the explained variance increased substantially to 42.6% (ΔR2 = 0.308, ΔF (4,199) = 28.64, P < 0.001). In this full model, perceived stress (β = 0.39, P < 0.001) and poor sleep quality (β = 0.28, P < 0.001) emerged as the strongest predictors. Positive communication attitudes retained a small but significant protective effect (β = -0.16, P = 0.014), while daily smartphone use lost significance, indicating that the psychosocial variables may partially mediate the relationship between usage time and nomophobia. The findings suggest that stress and sleep quality play a more central role than raw usage metrics in explaining nomophobia among nursing students (Figure 2).

Scatterplots illustrating the relationships between Nomophobia Questionnaire (NMP-Q) scores and key predictors: (Left) Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scores, (middle) Communication Skills Attitude (CSAS)-Positive Attitude Scale (PAS) scores, and (right) Stress Index in Nursing Students (SINS) scores. Each plot includes the fitted regression line with 95% confidence intervals, highlighting significant associations observed in the hierarchical regression analysis.

4.4. Bayesian Regression Evidence

The Bayesian analysis reinforced the frequentist results, offering a probabilistic interpretation of the data (Table 3). The Bayes factor comparing the full model to the null model (BF10 = 142.6) provided strong evidence favoring the inclusion of sleep quality, communication attitudes, and stress as predictors of nomophobia. Posterior means for key predictors were consistent with the frequentist beta coefficients, and the 95% credible intervals for stress, sleep quality, and positive communication attitudes excluded zero. The posterior probability that stress positively predicts nomophobia was 0.998, and the probability that positive communication attitudes negatively predict nomophobia was 0.981. These results indicate that the observed relationships are not only statistically significant in a frequentist sense but are also highly probable in a Bayesian framework, lending strong credibility to the robustness of the model.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between nomophobia and key psychosocial factors — sleep quality, communication skills attitudes, and perceived stress — among nursing students in Kashan, Iran. The results demonstrated that nomophobia is moderately prevalent in this population and is significantly associated with poorer sleep quality, higher stress levels, and less positive attitudes toward communication skills training. These findings provide nuanced insight into the psychological correlates of nomophobia within a clinical education context and suggest important targets for intervention.

The observed positive association between nomophobia and poor sleep quality aligns with a substantial body of research documenting the detrimental effects of excessive smartphone use on sleep parameters among university students (23, 24). These studies emphasize that mobile phone overuse disrupts circadian rhythms and sleep architecture, leading to daytime fatigue and cognitive impairments. Our findings extend this literature by focusing on nursing students, who face particular academic and clinical demands that may exacerbate the impact of sleep disturbances on functioning. However, some studies have reported weaker or non-significant associations between mobile phone use and sleep quality when controlling for confounders such as mental health or lifestyle factors (25), suggesting that the relationship may be context-dependent. These discrepancies underscore the need for further research investigating mediating and moderating variables in this relationship.

Perceived stress was identified as the most robust predictor of nomophobia in both hierarchical regression and Bayesian analyses. Our correlation of R = 0.51 and regression coefficient of β = 0.39 for stress-nomophobia are notably stronger than those reported in prior studies (5, 26), suggesting a particularly pronounced relationship in nursing students under clinical training pressures. This finding is consistent with theoretical frameworks positing that problematic smartphone use may serve as a maladaptive coping mechanism to alleviate stress and anxiety (27, 28). Similarly, several empirical studies among college students and healthcare professionals have reported significant positive associations between perceived stress and nomophobia (29, 30). However, conflicting evidence exists, with some investigations suggesting no direct link between stress and mobile phone dependency once depression or personality traits are accounted for (31).

To address nomophobia, interventions such as CBT-based stress management programs incorporating smartphone usage tracking applications and sleep hygiene workshops tailored for nursing students could be effective in reducing dependency and improving well-being in nursing schools. Our results highlight the importance of considering stress management interventions within nursing education to potentially reduce nomophobic behaviors and improve psychological well-being.

The negative association between positive attitudes toward communication skills and nomophobia is a novel contribution that adds to the limited but growing literature on this topic. Previous research has underscored the role of interpersonal competencies in buffering against maladaptive technology use (32), and our findings support the hypothesis that students who value and engage in communication training may possess better coping resources, reducing dependence on digital devices as substitutes for face-to-face interactions. Conversely, the lack of a significant relationship between negative communication attitudes and nomophobia contrasts with some prior studies reporting that social anxiety and communication apprehension can exacerbate nomophobia (33). This discrepancy may reflect cultural or educational differences in the nursing student population and warrants further exploration.

Interestingly, daily smartphone use was a significant predictor of nomophobia only before accounting for psychosocial variables, indicating that stress, sleep quality, and communication attitudes may mediate or confound this association. This finding resonates with critiques of simplistic screen-time paradigms that neglect psychological context (34). The Stress-Coping Model supports this interpretation, suggesting that it is the psychological response to stress, rather than mere usage time, that drives nomophobic behaviors (14). Our results emphasize the importance of integrating psychosocial dimensions into conceptual models of nomophobia, moving beyond mere usage metrics to understand underlying drivers of problematic mobile phone attachment.

Methodologically, the combination of frequentist and Bayesian analytic approaches enhanced the rigor and interpretability of our findings. Bayesian regression provided probabilistic evidence that complemented P-value significance, allowing for richer conclusions about predictor credibility and effect sizes. This dual-method strategy has been advocated in recent behavioral health research to improve reproducibility and nuanced interpretation (35).

Nonetheless, limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, and the reliance on self-report measures introduces potential biases. Furthermore, cultural factors, such as Iran’s high smartphone penetration and reliance on social media despite censorship, may influence nomophobia’s prevalence and expression, potentially limiting generalizability to Western populations with different digital habits or access to mental health resources. Comorbid mental health conditions, such as anxiety or depression, which were not assessed, could also confound the observed relationships. Longitudinal designs and objective behavioral assessments are needed to clarify temporal dynamics and causal pathways.

5.1. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that nomophobia among nursing students is significantly associated with perceived stress and poor sleep quality, with positive communication skills attitudes serving as a protective factor. These findings underscore the need for holistic interventions addressing psychosocial well-being in nursing education. Implementing CBT-based stress management programs with smartphone usage tracking and sleep hygiene workshops could mitigate nomophobia’s impact, supporting students’ psychological and professional well-being in high-pressure academic and clinical environments.

5.2. Future Studies

Future research should employ mediation analyses to explore stress as a mediator between sleep quality and nomophobia, elucidating underlying mechanisms. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) testing the efficacy of digital detox programs, CBT-based interventions, or communication skills training are needed to validate practical solutions. Additionally, studies in diverse cultural settings, particularly in Western populations, would enhance generalizability and clarify the role of cultural and digital contexts in nomophobia.