1. Background

Over the past decade, the use of social media has expanded rapidly, a trend particularly notable among young people and university students (1). Platforms such as Instagram provide constant access to content and instant social interactions, creating new educational and communicative opportunities while simultaneously increasing the risk of excessive use and behavioral dependency (2). Social media addiction is defined as a pattern of compulsive behaviors, lack of control, and continued use despite negative consequences, potentially disrupting mental health and daily functioning (3).

Social media dependency can have wide-ranging mental and physical health consequences, including increased anxiety and depression, sleep disturbances, reduced concentration, avoidance behaviors, and impaired interpersonal relationships (4). Among university students, particularly those in medical sciences, such dependency extends beyond personal impairments and can influence clinical learning, workplace efficiency in hospital settings, patient care quality, and clinical safety (5). Nursing and midwifery students trained in clinical environments face unique emotional and occupational pressures; alongside these stressors, unhealthy Instagram use can diminish their ability to concentrate during clinical care, make sound clinical decisions, and engage professionally with patients (6).

To design preventive interventions and empower students, it is essential first to identify the presence and severity of the problem via reliable assessment tools tailored to the cultural context (7). While numerous instruments exist to measure general internet or social media addiction, such as the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale (BFAS), and the Social Media Addiction Scale (SMAS), these tools were developed for broader or text-based social media platforms and do not fully capture the visual and image-centered engagement characteristics of Instagram (8). Therefore, there is a growing need for an instrument specifically focused on Instagram addiction that can assess behavioral and cognitive patterns unique to this platform, especially in professional training contexts.

The Test for Instagram Addiction (TIA), developed by Lancy D’Souza and colleagues, consists of 26 items across six components — lack of control, withdrawal, escapism, health and interpersonal issues, excessive use, and obsession — covering different dimensions of Instagram dependency (9). While the TIA has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties in its original context, direct application across cultures and professional groups may be problematic without proper linguistic and conceptual adaptation.

Notably, prior validations have focused on general youth or student populations rather than individuals in clinical education environments. Nursing and midwifery students operate in structured, high-stakes settings that demand constant attention and ethical engagement with patients; thus, Instagram addiction in this context may manifest differently.

The novelty of the present study lies in culturally adapting and validating the TIA specifically for nursing and midwifery students in clinical learning environments in Iran — an area previously unexplored. Unlike general social media tools, this version aims to assess how visual engagement and compulsive Instagram use intersect with academic and clinical performance. This study fills a methodological and cultural gap in digital behavior assessment tools within healthcare education.

2. Methods

This psychometric study aimed to culturally adapt and validate the TIA among nursing and midwifery students engaged in clinical training at teaching hospitals in Kerman Province. Although the original TIA was developed among young adults in Karnataka and Kerala (India), this study involved nursing and midwifery students in Kerman, Iran, owing to the growing prevalence of social media use in this population and the need for a culturally validated measure for clinical education contexts. The instrument’s core constructs are universal, but linguistic and contextual adjustments are necessary to ensure cultural relevance.

The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences (IR.KMU.REC.1404.315).

2.1. Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process

To culturally adapt and translate the TIA, the standard forward–backward translation method was applied. Initially, two bilingual translators — one with expertise in medical sciences and the other without medical specialization — independently translated the questionnaire into Persian (10). The translated versions were then compared, merged, and revised to preserve both technical meaning and natural language use. Next, two additional translators, blinded to the original version, back-translated the merged Persian version into English to ensure that the concepts remained intact (10). Finally, a committee consisting of experts in psychometrics, medical sciences, and linguistics reviewed all the versions and prepared a prefinal version. This version was piloted on a sample of 30 nursing and midwifery students to assess clarity and cultural appropriateness, with final modifications made on the basis of feedback.

2.2. Study Population and Data Collection

The study population comprised nursing and midwifery students undergoing clinical training in teaching hospitals across Kerman Province in 2025. Cluster sampling was used: First, six nursing and midwifery faculties in the province were randomly selected. From each selected faculty, a list of students currently engaged in clinical placements was obtained, and participants were randomly chosen from these lists.

The sample size was determined on the basis of accepted psychometric research standards and statistical power requirements: 400 students for exploratory factor analysis (EFA), 300 students for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), 100 students for reliability testing (Cronbach’s alpha and test-retest), and another 100 students for concurrent validity assessment (11). The samples for EFA (n = 400), CFA (n = 300), and reliability/concurrent validity testing (n = 100 + 100) were independent and nonoverlapping to prevent bias and ensure the robustness of the results.

2.3. Sampling Method

A multistage cluster sampling method was employed. Faculties served as clusters, from which random samples of clinically active students were selected, ensuring representative coverage of nursing and midwifery students across Kerman Province.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible participants were nursing and midwifery students who were engaged in clinical training at teaching hospitals in Kerman Province and who provided informed consent. Students with a history of psychological disorders, serious medical conditions, substance or medication abuse, or unwillingness to continue participation were excluded. Questionnaires with incomplete responses were also removed to maintain data quality.

2.5. Research Instruments

Test for Instagram Addiction (TIA): The TIA consists of 26 items grouped into six subscales: Lack of control (items 1-5), disengagement (items 6 - 11), escapism (items 12 - 16), health and interpersonal troubles (items 17 - 20), excessive use (items 21 - 22), and obsession (items 23 - 26). Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale (e.g., from “Never” to “Always”), with total scores ranging from 0–78. Each response is scored between 0 and 3, and the sum of all the items represents the overall score. Previous studies have demonstrated good validity and high reliability for this instrument, with Cronbach’s alpha reported at approximately 0.93 in initial samples, indicating excellent internal consistency (9).

General Phubbing Scale (GPS): Developed by Chotpitayasunondh and colleagues in 2018, the GPS contains 15 items rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (5). It comprises four subscales: Nomophobia (items 1 - 4), Interpersonal Conflict (items 5 - 8), Self-Isolation (items 9 - 12), and Problem Acknowledgment (items 13 - 15). The developers reported Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.93 for the total scale and 0.84, 0.87, 0.83, and 0.82 for the subscales. The GPS has been validated for use across various settings and age groups. In Iran, a study by Hasan-Esfahani et al. confirmed its construct validity, convergent validity (correlation coefficient of 0.77 with the Mobile Phone Addiction Scale), and good reliability, supporting its applicability among the general Iranian population. In the present study, the GPS was used to assess the concurrent validity of the TIA, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 obtained (12).

In this study, the questionnaire was validated in several stages to ensure the instrument’s validity and reliability.

Although the original TIA had established psychometric properties, content validity [the content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity Index (CVI)] was reassessed as part of the cultural adaptation process to ensure conceptual, linguistic, and contextual equivalence for the Iranian nursing and midwifery student population. This step aligns with the WHO and Beaton guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. To assess content validity, 10 experts in psychology, medical education, and linguistics evaluated each item via Lawshe’s three-point Scale (“Essential,” “Useful but not essential,” “Not essential”) for CVR and a four-point scale (1 = not relevant to 4 = highly relevant) for CVI across simplicity, clarity, and relevance dimensions (13).

Concurrent validity was evaluated by calculating the correlation between the total score of the TIA and the GPS Questionnaires. The GPS was selected for concurrent validity because both phubbing and Instagram addiction share core features of compulsive smartphone use, social withdrawal, and impaired interpersonal engagement. The GPS reflects behavioral and cognitive components similar to those underlying Instagram addiction, thus providing a theoretically and empirically grounded external criterion.

Construct validity was examined through EFA and CFA. In the EFA, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were first calculated. The latent factors were then extracted via the principal axis factor (PAF) method with varimax rotation. Items loading on each of the six factors were identified, and all factor loadings exceeded 0.50, indicating a strong association between the items and their respective factors (14). PAF was chosen because it extracts common variance and is appropriate for identifying underlying constructs rather than maximizing total variance, as in principal component analysis (PCA). Rotation was initially performed via varimax rotation for clarity and interpretability of factor loadings, but the results were also verified via oblimin rotation given the theoretical likelihood of correlated psychological dimensions. The two methods produced comparable factor structures, confirming the robustness of the factor solution.

The CFA was subsequently conducted to assess the fit of the model derived from the EFA. Model fit indices included the chi-square test, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.08), comparative fit Index (CFI > 0.95), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > 0.95), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR < 0.05), normed fit Index (NFI > 0.95), incremental fit Index (IFI > 0.95), relative fit Index (RFI > 0.95), and root mean square residual (RMR < 0.05) (15). The CFA was conducted to confirm the six-factor structure identified by the EFA and to validate the theoretical model of the TIA. As a standard psychometric procedure, CFA verifies construct validity from both data-driven and theoretical perspectives. Given that the Persian version was culturally adapted for Iranian nursing and midwifery students, this analysis was essential to confirm the stability, model fit, and replicability of the structure from the original Indian version, ensuring that the adapted instrument retained its theoretical coherence and multidimensional nature.

Reliability was evaluated via Cronbach’s alpha, split-half reliability, test–retest, and Guttman’s lambda coefficients (λ1 - λ6) to provide a more comprehensive assessment of internal consistency. Test–retest reliability was calculated over a two-week interval between administrations of the TIA.

Data analysis: Prior to analysis, the collected data were checked for completeness, as were the presence of outliers or missing values. Missing data were checked and handled through listwise deletion, as the number of missing values was minimal (<5%). No extreme outliers were identified. Statistical analyses were conducted via IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and LISREL version 8.8 (Scientific Software International, Inc., Skokie, IL, USA). In the descriptive phase, measures of central tendency and dispersion, including the mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage, were used to describe demographic characteristics and main variables. In the inferential phase, facial validity was assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively; content validity was determined via the CVR and CVI; concurrent validity was examined via Pearson’s correlation coefficient; and construct validity was evaluated via EFA (KMO and Bartlett’s test) and CFA (model fit indices). Reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s alpha, split-half, and test–retest methods, with the significance level set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

The demographic findings indicated that the majority of the participants were aged 20–25 years (44.61%), female (60.50%), single (71.06%), enrolled in a bachelor’s programme (79.00%), and were studying nursing (70.83%) (Table 1). This distribution was generally consistent across the exploratory, confirmatory, reliability, and concurrent validity phases.

| Variable | Concurrent Number | Exploratory Number | Confirmatory Number | Reliability Number | Total Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Less than 20 years old | 36 (37.11) | 133 (34.19) | 101 (34.12) | 32 (32.32) | 302 (34.28) |

| 20 to 25 years old | 40 (41.24) | 183 (47.04) | 128 (43.24) | 42 (42.42) | 393 (44.61) |

| Above 25 years old | 21 (21.65) | 73 (18.77) | 67 (22.64) | 25 (25.25) | 186 (21.11) |

| Gender | |||||

| Girl | 62 (63.92) | 239 (61.44) | 175 (59.12) | 57 (57.58) | 533 (60.50) |

| Boy | 35 (36.08) | 150 (38.56) | 121 (40.88) | 42 (42.42) | 348 (39.50) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 74 (76.29) | 256 (65.81) | 223 (75.34) | 73 (73.74) | 626 (71.06) |

| Married | 23 (23.71) | 133 (34.19) | 73 (24.66) | 26 (26.26) | 255 (28.94) |

| Education level | |||||

| Bachelor | 78 (80.41) | 305 (78.41) | 242 (81.76) | 71 (71.72) | 696 (79.00) |

| Master’s and above | 19 (19.59) | 84 (21.59) | 54 (18.24) | 28 (28.28) | 185 (21.00) |

| Academic group | 64 (65.98) | 275 (70.69) | 208 (70.27) | 77 (77.78) | 624 (70.83) |

| Nursing | |||||

| Midwifery | 33 (34.02) | 114 (29.31) | 88 (29.73) | 22 (22.22) | 257 (29.17) |

a Values are expressed as No (%).

The content validity of the TIA was evaluated by 10 experts via the CVR and CVI indices. The results revealed that the item CVRs ranged from 0.80 to 1.00 — above Lawshe’s critical value for 10 experts (0.62) — and that the CVIs ranged from 0.833 to 0.967, indicating high clarity, simplicity, and relevance for all 26 items and demonstrating comprehensive coverage of the construct’s dimensions.

Concurrent validity analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between the total score of the TIA and the GPS score (r = 0.76, P < 0.01), confirming the concurrent validity of the TIA. After all the raw scores were converted to a 100-point scale for easier comparison, the total mean score of the TIA was 53.00, whereas the total mean score of the GPS was 51.03. The mean scores of the TIA subscales (0 - 100 scale) were as follows: Lack of control = 52.33, withdrawal = 55.61, escape from reality = 48.47, health and interpersonal problems = 54.83, excessive use = 53.00, and obsession = 53.83. Similarly, the mean scores for the GPS subscales were as follows: Nomophobia = 53.94, Interpersonal Conflict = 50.94, Self-Isolation = 50.81, and Problem Acknowledgment = 47.50. The close similarity in mean scores across both instruments indicates that participants exhibited relatively comparable moderate levels of Instagram addiction and phubbing behaviors. This consistent pattern supports the alignment of the two constructs and reinforces the concurrent validity and psychometric soundness of the TIA.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted via the PAF extraction method with varimax orthogonal rotation to identify the underlying factor structure of the TIA. The KMO measure of sampling adequacy was 0.899, demonstrating excellent suitability of the data for factor analysis, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 5180.669, df = 325, P < 0.001), confirming the appropriateness of the correlation matrix. The communality values ranged from 0.44 to 0.78, indicating that all the items adequately contributed to explaining the shared variance among the observed variables. The rotated solution yielded six interpretable components with eigenvalues greater than one, collectively explaining 60.22% of the total variance (Table 2). These extracted dimensions included lack of control (items 1 - 5), withdrawal (items 6 - 11), escape from reality (items 12 - 16), health and interpersonal problems (items 17 - 20), excessive use (items 21 - 22), and obsessions (items 23 - 26). All the items loaded significantly on their respective factors, with loadings ranging from 0.56 - 0.81, indicating a strong and distinct factor structure (Table 2). These findings collectively confirm that the six-factor model provides a psychometrically sound and multidimensional representation of Instagram addiction, demonstrating the robustness and construct validity of the TIA Scale.

| Variables | Factor | Communalities | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal | Lack of Control | Escape from Reality | Obsession | Health and Interpersonal Problems | Excessive Use | Initial | Extraction | |

| i1 | 0.12 | 0.80 a | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.62 | 0.7 |

| i2 | 0.03 | 0.81 a | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.69 |

| i3 | 0.13 | 0.74 a | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.59 |

| i4 | 0.15 | 0.77 a | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| i5 | 0.11 | 0.74 a | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.61 |

| i6 | 0.74 a | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.59 |

| i7 | 0.73 a | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.54 | 0.6 |

| i8 | 0.68 a | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| i9 | 0.69 a | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.52 |

| i10 | 0.71 a | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 0.58 |

| i11 | 0.70 a | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.56 |

| i12 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.70 a | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| i13 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.78 a | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| i14 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.72 a | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.6 |

| i15 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.76 a | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.6 | 0.65 |

| i16 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.79 a | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.6 | 0.67 |

| i17 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.72 a | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

| i18 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.70 a | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.58 |

| i19 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.71 a | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.57 |

| i20 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.74 a | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.61 |

| i21 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.56 a | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| i22 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.78 a | 0.42 | 0.72 |

| i23 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.77 a | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.66 |

| i24 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.73 a | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.6 |

| i25 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.76 a | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.65 |

| i26 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.68 a | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.52 |

| Loadings | ||||||||

| Total | 3.41 | 3.24 | 3.14 | 2.44 a | 2.34 | 1.09 | - | - |

| Variance b | 13.11 | 12.45 | 12.09 | 9.40 | 8.99 | 4.18 | - | - |

| Cumulative b | 13.11 | 25.56 | 37.66 | 47.05 | 56.04 | 60.22 | - | - |

a Factor loadings ≥ 0.50 in the exploratory factor analysis..

b Variables are expressed as No (%).

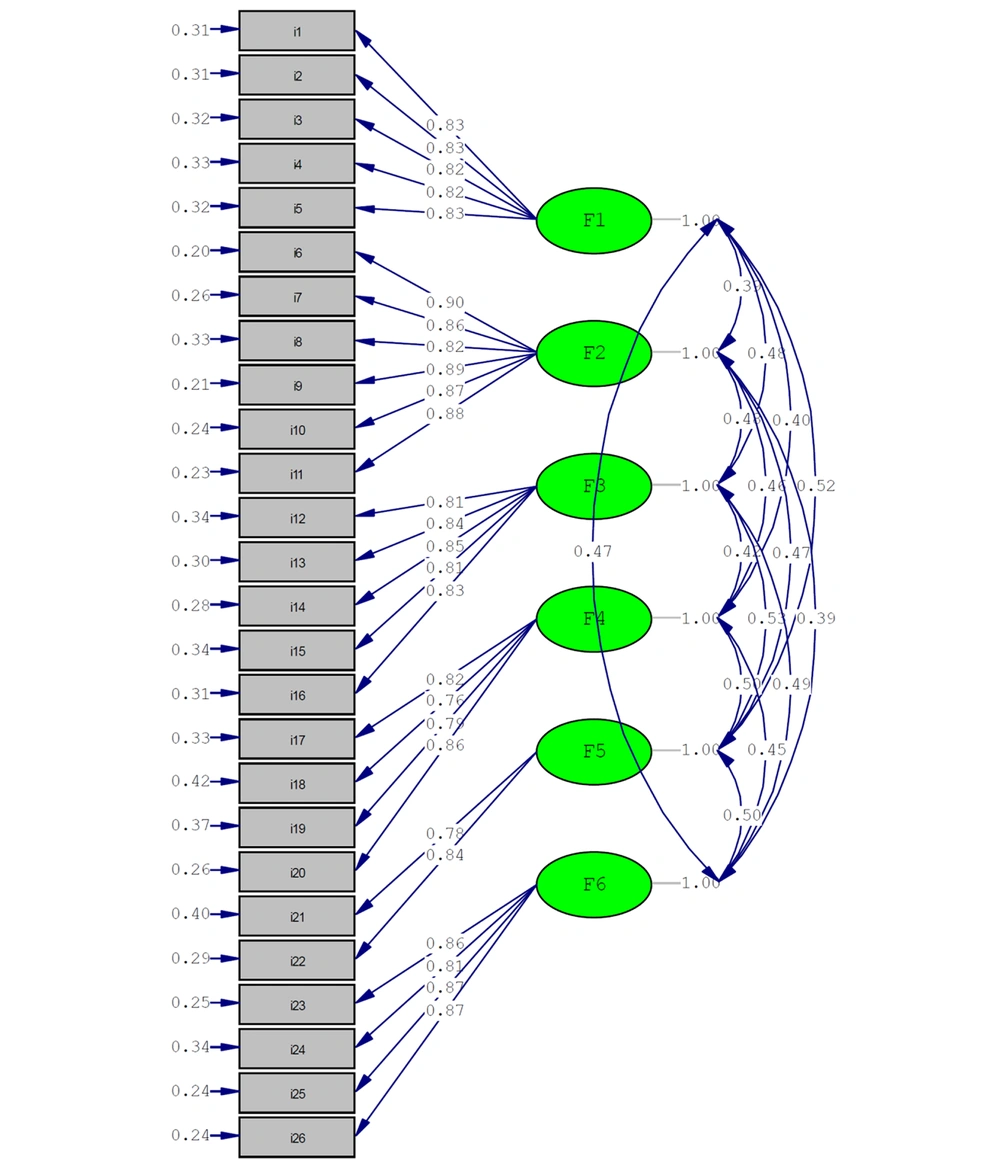

The CFA was conducted via the maximum likelihood estimation method to verify the six-factor structure of the TIA identified in the exploratory phase. The hypothesized model, including six latent dimensions — lack of control, withdrawal, escape from reality, obsession, health and interpersonal problems, and excessive use — demonstrated an excellent fit to the data, as indicated by the following fit indices: χ² (284) = 538.78, P < 0.001; CFI = 0.98 [95% CI (0.96 - 0.99)]; TLI = 0.97 [95% CI (0.95 - 0.98)]; RMSEA = 0.051 [90% CI (0.043 - 0.058)]; SRMR = 0.047; and ECVI = 2.14 [95% CI (1.95 - 2.38)]. All standardized factor loadings were statistically significant (P < 0.001) and ranged from 0.56 - 0.81, with 95% confidence intervals between 0.52 and 0.84, confirming the stability and precision of the parameter estimates. The squared multiple correlations (R²) of the observed variables ranged from 0.31–0.68, indicating that a substantial proportion of the variance in each item was explained by its respective latent construct. Interfactor correlations were moderate (r = 0.39 - 0.53, P < 0.001), with 95% confidence intervals between 0.33 and 0.61, suggesting that while the dimensions are conceptually related, they remain distinct aspects of Instagram addiction. The reliability and validity indices further supported the robustness of the model: The internal consistency was strong across the subscales (Cronbach’s α = 0.79 - 0.88), the composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.81 - 0.89, and the average variance extracted (AVE) ranged from 0.54 - 0.67, indicating satisfactory convergent validity. Additionally, discriminant validity was established, as the square root of each factor’s AVE exceeded the corresponding interfactor correlations. Collectively, these findings confirm that the six-factor structure provides a psychometrically sound and theoretically coherent representation of Instagram addiction, aligning closely with the exploratory results and supporting the multidimensional and robust nature of the TIA Scale (Figure 1).

Reliability was assessed via multiple statistical methods. The Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.919, indicating excellent internal consistency for all 26 items. Split-half reliability showed a correlation of 0.631, with Spearman–Brown and Guttman coefficients of 0.774 and 0.773, respectively, further confirming internal consistency. Subscale reliability was also high: Lack of control (α = 0.883), withdrawal (α = 0.929), escapism (α = 0.905), health and interpersonal problems (α = 0.898), excessive use (α = 0.934), and obsession (α = 0.906). Additionally, Guttman’s lambda coefficients (λ1 - λ6) were calculated as follows: λ1 = 0.883, λ2 = 0.924, λ3 = 0.919, λ4 = 0.773, λ5 = 0.902, and λ6 = 0.969, demonstrating strong reliability across all indices. The test–retest correlation over a two-week interval was 0.89 (P < 0.01), demonstrating strong temporal stability. Overall, the TIA demonstrated excellent reliability and robustness.

4. Discussion

The overall findings indicate that all 26 items of the TIA Questionnaire are appropriate in terms of content and clarity and comprehensively represent all dimensions of Instagram addiction. The CVR and CVI values, which exceeded the acceptable thresholds, confirmed the necessity, clarity, and relevance of each item to the construct. This finding aligns with the original study by Tevin John et al., who demonstrated that consulting 10 subject-matter experts in psychology and social sciences ensures both the conceptual and practical importance of all items, with no unnecessary elements present in the instrument (9).

The results also revealed that the TIA is highly concordant with established measures of social media addiction, such as the GPS, with the total TIA score positively and strongly correlated with these scales. This supports the high concurrent validity of the Questionnaire and its ability to assess multiple dimensions of Instagram addiction comprehensively and accurately, in line with existing theoretical frameworks and scientific models of internet and social networking addiction.

Findings from both EFA and CFA confirmed the six-factor structure of the TIA — Lack of Control, Withdrawal, Escapism, Health and Interpersonal Problems, Excessive Use, and Obsession — with all items demonstrating adequate factor loadings, satisfactory explained variance, and model fit indices indicative of an excellent fit. These results, which are consistent with those of Tevin John et al., affirm that the questionnaire measures distinct yet related dimensions of Instagram addiction (9). Comparisons with other internet and social media addiction measures reveal notable conceptual overlap: For example, Young’s IAT covers psychological and behavioral domains such as emotional investment and time management (16); the BFAS comprises six factors — salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse (17); and the SMAS includes the dimensions of preoccupation, mood modification, relapse, and conflict (18). This comparison indicates that the TIA shares conceptual compatibility with well-established tools while maintaining comprehensive coverage of Instagram-specific addictive behaviors, making it a valid and practical instrument for both research and clinical interventions.

Reliability analysis demonstrated excellent internal consistency for the total scale (α = 0.919) and high reliability across all the subscales. Test–retest correlations further confirmed the instrument’s strong temporal stability. These results are consistent with those of the original study, which reported an overall α of approximately 0.931 and subscale values ranging from 0.680 to 0.863 (9). Collectively, these findings indicate that the items are well designed and elicit stable and coherent responses and that the TIA possesses strong reliability.

Study limitations include sampling constraints, the self-reported nature of the data, the cross-sectional design, and the cultural adaptation process of the questionnaire. The study population was limited to nursing and midwifery students engaged in clinical education in Kerman Province, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other academic disciplines and geographic regions. Therefore, this limitation should be interpreted with caution. Future studies are strongly recommended to replicate the validation process among students from other health-related and nonhealth disciplines, as well as in different provinces across Iran, to assess the stability, reliability, and factorial invariance of the instrument in more diverse samples. As the data were self-reported, response bias is possible; therefore, incorporating mixed behavioral assessment methods is recommended. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and longitudinal studies are suggested. Finally, cultural adaptation was tailored to a specific population, and further validation of the questionnaire across different cultural and linguistic contexts is recommended to enhance its generalizability.

4.1. Conclusions

This study confirms that the Persian Instagram Addiction Test (TIA) is valid and reliable across content, construct, and concurrent validity, with strong internal consistency and temporal stability. All 26 items were essential, clear, and relevant, supporting a six-factor structure: Lack of control, withdrawal, escapism, health and interpersonal problems, excessive use, and obsession. Cronbach’s alpha and test–retest results confirmed reliability. The tool is suitable for research and clinical assessment. Limitations include a sample limited to nursing and midwifery students, self-reported data, a cross-sectional design, and narrow cultural adaptation. Broader samples, mixed methods, and longitudinal designs are recommended.