Dear Editor,

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly transformed the daily lives of children worldwide, leading to a significant increase in screen time through television, video games, and digital media (1). During lockdowns, reduced social interactions and growing reliance on digital devices gave rise to a clinical phenomenon where children exhibit symptoms remarkably similar to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — a condition increasingly referred to as "Virtual Autism" (2). Rooted in the hypothesis of sensory-motor and social deprivation, "Virtual Autism" occurs when a child spends hours in passive or one-sided interaction with screens, depriving them of the rich, multisensory experiences of the real world, such as exploring object textures, face-to-face interaction, physical play, and problem-solving in complex environments (1). This deprivation can lead to delays in developmental milestones, weaknesses in non-verbal communication skills (e.g., eye contact), language poverty, and an inability to understand social cues (3).

Now, in the post-COVID era, child mental health specialists are encountering a surge of patients presenting with symptoms of social isolation, speech delay, and repetitive behaviors. The primary clinical challenge is the differential diagnosis between an intrinsic, persistent neurodevelopmental disorder and a set of acquired, environment-dependent symptoms stemming from deprivation (1, 4). Notably, these symptoms often improve with reduced screen exposure and a return to social activities (5). This reversibility distinguishes it from classic autism and underscores the environmental, rather than neurodevelopmental, origin of these symptoms. This distinction is of paramount clinical importance as it completely alters the intervention pathway, prognosis, and psychological burden on the family. What follows is a case report of a 6-year-old boy that clearly illustrates this diagnostic challenge.

A 6-year-old boy was referred to our occupational therapy clinic by his parents with chief complaints of "social withdrawal", "lack of eye contact", and "repetitive play". The parents reported that these symptoms had become more pronounced over the past two years. His developmental history was unremarkable regarding pregnancy and birth. The child also acquired gross motor skills (such as sitting, crawling, walking) within the normal age range. Parents reported first words at 12 months and two-word combinations at around 2 years of age. They emphasized that the child had been very social and curious until the age of 3. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the imposition of nationwide lockdowns when the child was 3.5 years old, his time spent on a tablet watching animations and playing simple games gradually increased from 1 - 2 hours to over 5 hours per day. This pattern continued even after the kindergarten reopened, as the child showed no interest in group play, and the parents resorted to the tablet to manage his behavior. According to the parents, reduced eye contact, a shrinking active vocabulary, and an obsessive interest in spinning the wheels of toy cars began during this same period.

During the clinical occupational therapy assessment, the child avoided sustained eye contact, though he would occasionally and briefly glance. His speech was limited to short, request-based phrases. In the playroom, instead of engaging with the therapist, he occupied himself with lining up cars alone. The neurological examination was entirely normal. Standardized cognitive tests (such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale) showed scores in the borderline-to-normal range. Screening with the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) yielded a score of 17, which is above the cutoff point, indicating the need for more detailed assessment.

In the diagnostic-therapeutic process, given the highly suggestive history of symptom onset following excessive screen time increase and the lack of clear evidence of disorder in the early years, the initial diagnosis of ASD was met with serious doubt. The parents were educated that the child's symptoms might be an "adaptive response" to an environment poor in sensory and social stimulation, rather than a lifelong disorder. An immediate intervention plan was designed and implemented, involving structured and gradual screen elimination, environmental substitution and enrichment, and parental support. The time spent on tablets and television was reduced over two weeks to less than 1 hour per day (and only interactive/educational content with parental co-viewing).

Sessions of sensory-motor play therapy (playdough, sand play), daily park visits and cycling, imitative and symbolic play with active parental participation, and weekly playdates with a peer were established. Regular counseling sessions were also held to follow progress, address obstacles, and strengthen the parents' interactive skills.

After a 3-month follow-up, remarkable and measurable improvement was observed. Eye contact increased significantly, the child used simpler and more sentences to express his needs, and he participated in imaginative play with his mother. The SCQ score in the re-evaluation dropped to 9. This rapid and positive response to a purely environmental intervention strongly reinforced the sensory-motor deprivation hypothesis and effectively ruled out the likelihood of an ASD diagnosis.

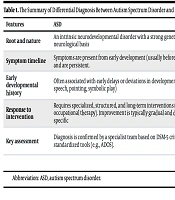

This case is a clear example of an emerging diagnostic challenge in the digital and post-pandemic age. A cross-sectional study in 2021 clearly showed that hours spent on electronic devices are correlated with higher scores on the SCQ. In that study, the prevalence of an SCQ score ≥ 15 (indicative of deficits in social skills) was 19.7% in children who used devices for more than 3 hours a day, while this rate was only 7.84% in the group with less than 2 hours of use (6). This statistic confirms a quantitative association between screen time and autism-like symptoms. The differential diagnosis between ASD and screen-induced deprivation is based on several key pillars, summarized in the table below (Table 1) (7).

| Features | ASD | Autism-like Symptoms from Sensory-Motor Deprivation |

|---|---|---|

| Root and nature | An intrinsic neurodevelopmental disorder with a strong genetic and neurological basis | An acquired, environment-dependent reaction to an environment poor in stimulation. |

| Symptom timeline | Symptoms are present from early development (usually before age 3) and are persistent. | Symptoms appear or intensify after a period of excessive and prolonged screen use. |

| Early developmental history | Often associated with early delays or deviations in development (in speech, pointing, symbolic play) | Early developmental milestones may be normal. Skill regression is observed following the period of deprivation. |

| Response to intervention | Requires specialized, structured, and long-term interventions (e.g., ABA, occupational therapy). Improvement is typically gradual and domain-specific | Rapid and significant response to environmental intervention; symptoms decrease significantly or resolve with reduced screen time and enriched real-world interaction |

| Key assessment | Diagnosis is confirmed by a specialist team based on DSM-5 criteria and standardized tools (e.g., ADOS). | Taking a detailed, quantitative history of screen time and observing response to a trial period of screen reduction and environmental enrichment is crucial |

Abbreviation: ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

As this case demonstrated, an ASD diagnostic label should not be hastily applied based solely on a set of surface symptoms. When facing any child with autism-like symptoms, especially in the post-COVID context, obtaining a deep and quantitative history of digital technology use patterns is an absolute necessity. We suggest that a 2 - 3 month "diagnostic-therapeutic trial period" involving drastic screen time reduction and implementation of an interaction enrichment program be considered part of the initial evaluation protocol. A positive response to this intervention can prevent mislabeling — which carries heavy psychological and social consequences — and guide the family toward the correct path of rehabilitation and natural child development. Increasing awareness among pediatricians, psychiatrists, and psychologists about this critical distinction is an essential step toward more accurate assessment and effective intervention for the current generation of children.