1. Background

Preeclampsia (PE) is one of the main health complications of pregnancy. It is a multi-system disorder that develops in pre-normotensive women after the 20th week of pregnancy and is characterized by end-organ failure, proteinuria, or new-onset hypertension; the condition can persist for up to 6 weeks after delivery (1). The PE affects about 3% of all pregnancies, and approximately 5% to 10% of pregnancies are affected by hypertensive disorders. These women are at an increased risk of maternal and fetal mortality, as well as significant fetal morbidity, particularly if the PE is severe (2).

Clinically, distinguishing between mild (mPE) and severe preeclampsia (sPE) based on the severity of symptoms is critical. This disorder can result in HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets), eclampsia (seizures as a consequence of cerebral artery disease), or disseminated intravascular coagulation (3, 4).

Increased plasma levels of β-thrombomodulin and platelet factor-4 (5, 6) and increased expression of platelet activation markers in women with PE indicate platelet activation in this disease (6, 7). There are still questions regarding the precise etiology of PE and effective prevention measures. One potential pathophysiological mechanism that can limit maternal blood flow to the placenta and result in some degree of ischemia is a deficiency in trophoblastic penetration of the maternal vascular bed (8, 9). Placental under-perfusion results in angiogenic responses that produce broad systemic and maternal endothelial dysfunction. The coagulation system may become active, vascular permeability and vasoconstriction may increase, and microangiopathic hemolysis may advance (10). The coagulation mechanism may be triggered by the interaction of platelets with the injured endothelium, enhancing the consumption and production of platelets in the bone marrow (11).

As part of the data collected from complete blood counts, platelet indices are available. They include the mean platelet volume (MPV), which reflects the function of the bone marrow, platelet distribution width (PDW), corresponding to the platelet size distribution, and platelet large cell ratio (P-LCR), representing the percentage of platelets greater than 12 fL (12, 13). In various clinical situations, elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) have recently garnered considerable interest as systemic indicators of inflammatory response. The PLR is reported to demonstrate improved activation of platelets, leading to the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis (14). The significance of numerous platelet indices as predictors of PE has previously been explored; however, the results remain debatable.

2. Objectives

The objective of this research was to investigate the diagnostic value of platelet parameters in PE.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Study Population

We conducted a retrospective case-control study at Imam Reza Hospital in Kermanshah, Iran, with the approval of our Local Ethics Council. The patients (n = 50) consisted of 16 females with mPE, 23 females with sPE, and 11 with HELLP syndrome. Healthy pregnant women (n = 50) receiving antenatal treatment were taken as controls. All infants were delivered from January 2015 to January 2020.

3.2. Ethical Approval

This research was approved by the Kermanshah University of Medical Science Regional Research Ethical Committee, which deemed that formal consent was not necessary due to the retrospective nature of the study.

3.3. Data Collection

Prior maternal medical history was typical in all instances. The gestational age was determined using obstetric ultrasonographic data from the previous menstrual cycle and/or the first trimester and verified using the new Ballard technique 1 hour after birth (15). The diagnostic criteria for mPE were persistent proteinuria (300 mg/day or more) and pregnancy-induced hypertension (blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or above, evaluated twice at least four hours apart). The diagnostic criteria for sPE were either a systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg on two occasions more than four hours apart, with proteinuria (300 mg/day or more); or a protein/creatinine ratio of 0.3 and serum creatinine of 1.1 mg/dL; or a doubling of blood creatinine level in the absence of any other renal disease. Additionally, the severe PE category included any patient with pulmonary edema, HELLP syndrome characterized by hemolysis, liver impairment, cerebral or visual disturbance, and/or thrombocytopenia [platelet count (PC) less than 100,000/Ml]. The following conditions were also excluded: Hereditary or acquired coagulation disorders, cancer, infections, chronic hypertension, gestational diabetes, hepatic and/or cardiovascular disease.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows (version 20.0). To evaluate the differences between cases and controls for normally and abnormally distributed continuous variables, the Student's t-test and the Mann-Whitney U-test were utilized. Diagnostic screening tests were used to assess the diagnostic cutoffs using the receiver operating characteristics (ROCs) curve with different parameters (based on test sensitivity and specificity). A P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

4. Results

One hundred women comprised four groups: The sPE (n = 23), mPE (n = 16), HELLP syndrome (n = 11), and a healthy control group (n = 50). Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of all groups. Gestational age was significantly higher in women with PE. Table 2 shows that there were significant differences in red blood cell (RBC), hematocrit (HCT), MPV, PC, PDW, red blood cell distribution width (RDW), PLR, and PC to MPV ratio (PLM) between the case and control groups. In the case group, MPV, PDW, and RDW were considerably decreased, whereas HCT, RBC, PC, PLR, and PLM were significantly higher. When the sPE and mPE were compared, a lower PLR was found in mPE compared to sPE (Table 3). In addition to low PC and PLM in the HELLP syndrome group, HCT and Hb were also higher in this group than in the sPE group.

| Variables | Cases (N = 50) | Control (N = 50) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 28.16 ± 6.91 | 29.92 ± 5.86 | 0.1 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 37.43 ± 3.7 | 32.63 ± 7.32 | < 0.001 |

| Parity | 0.94 ± 0.99 | 0.68 ± 0.93 | 0.1 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

| Variables | Cases (N = 50) | Control (N = 50) | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | ||

| HCT (%) | 35.37 ± 4.53 | 37.45 (37.45 - 39.92) | 37.74 ± 4.23 | 35.75 (31.92 - 38.72) | 0.01 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.20 ± 1.81 | 12.6 (11.77 - 13.62) | 12.6 ± 1.64 | 12.35 (11.17 - 13.42) | 0.4 |

| RBC (× 106/µL) | 4.24 ± 1.02 | 4.36 (4.12 - 4.75) | 4.4 ± 0.46 | 4.18 (3.7 - 4.4) | 0.008 |

| WBC (× 103/µL) | 11.22 ± 3.23 | 10.7 (8.85 - 13.12) | 11.02 ± 3.25 | 10.85 (8.97 - 13.47) | 0.6 |

| PC (× 103/µL) | 158.2 ± 89.71 | 197 (177.5 - 229) | 205.74 ± 58.99 | 153.5 (92.25 - 194.5) | < 0.001 |

| MPV (fL) | 10.73 ± 1.06 | 10.05 (9.4 - 10.1) | 10.26 ± 1.7 | 10.6 (10 - 11.35) | 0.02 |

| PDW (fL) | 15.02 ± 3.16 | 13.2 (12.07 - 15.27) | 13.93 ± 2.97 | 15 (12.8 - 16.35) | 0.05 |

| P-LCR (%) | 31.7 ± 7.93 | 26.5 (21.7 - 33.1) | 28.17 ± 8.77 | 31.3 (26.2 - 37.7) | 0.2 |

| RDW (%) | 14.26 ± 1.69 | 13.65 (13.1 - 14.62) | 14.01 ± 1.25 | 13.95 (13.4 - 14.72) | 0.04 |

| Neutrophil | 8.36 ± 2.90 | .55 (0.41 - 074) | 8.26 ± 3.05 | 0.57 (0.47 - 0.80) | 0.3 |

| Monocyte | 0.61 ± 0.26 | 7.76 (6.06 - 9.13) | 0.58 ± 0.25 | 7.78 (6.02 - 10.87) | 0.7 |

| Lymphocyte | 2.36 ± 0.81 | 1.97 (1.65 - 2.78) | 2.19 ± 0.72 | 2.37 (1.72 - 2.88) | 0.2 |

| PLR | 74.4 ± 46.87 | 93.81 (75.8 - 126.26) | 101.5 ± 36.8 | 67.93 (38.49 - 104.42) | < 0.001 |

| NLR | 4.01 ± 2.28 | 3.45 (2.71 - 4.72) | 4.22 ± 2.55 | 3.59 (2.6 - 4.53) | 0.6 |

| PLM | 15.64 ± 2.08 | 19.63 (16.03 - 23.53) | 20.61 ± 7.4 | 14.3 (8.05 - 18.89) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: HCT; hematocrit; Hb, hemoglobin; RBC; red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell; PC, platelet; MPV, mean platelet volume; PDW, platelet distribution width; P-LCR, platelet large cell ratio; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLM, PC to MPV ratio.

| Variables | HELLP (N = 11) | Sever (N = 23) | Mild (N = 16) | P1 b | P2 c | P3 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT (%) | 31.7 (27.8 - 36.5) | 36.8 (34.6 - 40.7) | 35.8 (31.55 - 38.52) | 0.004 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 9.9 (9.2 - 12.6) | 12.6 (11.6 - 14) | 12.7 (11.62 - 13.4) | 0.006 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| RBC (× 106/µL) | 3.98 (3.29 - 4.37) | 4.23 (4.05 - 4.51) | 4.15 (3.66 - 4.39) | 0.09 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| WBC (× 103/µL) | 11.1 (10 - 14.6) | 11 (8.7 - 13.9) | 10.5 (8.2 - 11.95) | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| PC (× 103/µL) | 90 (59 - 162) | 166 (134 - 228) | 105.5(75.75 - 220.25) | 0.004 | 0.06 | 0.2 |

| MPV (fL) | 10.4 (10 - 11.9) | 10.6 (10 - 12) | 10.6 (9.8 - 11.6) | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| PDW (fL) | 15.2 (13.2 - 22.8) | 14.9 (12.8 - 15.5) | 15.1 (11.9 - 16.2) | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| P-LCR (%) | 31.5 (27.6 - 39) | 31.3 (25.3 - 39.3) | 31.3 (24.4 - 35.4) | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| RDW (%) | 14.7 (13.5 - 15.2) | 14.1 (13.3 - 14.8) | 13.75 (13.4 - 14.55) | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Neutrophil | 0.63 (0.47 - 0.86) | 0.54 (0.29 - 0.74) | 0.73 (0.51 - 0.80) | 0.2 | 0.08 | 0.7 |

| Monocyte | 9.8 (6.8 - 11.95) | 7.96 (5.52 - 11.32) | 6.99 (5.88 - 8.73) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.02 |

| Lymphocyte | 2.37 (1.42 - 2.7) | 2.28 (1.7 - 2.77) | 2.66 (1.83 - 3.12) | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| PLR | 38.32(33.32 - 77.6) | 84.83 (54.66 - 112.25) | 58.49 (26.31 - 71.87) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.7 |

| NLR | 3.82 (2.82 - 7.95) | 3.77 (2.54 - 5.1) | 3.38 (2.1 - 3.82) | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| PLM | 6.98 (5.87 - 15.88) | 14.85 (11.7 - 22.4) | 10 (7.96 - 21.6) | 0.009 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Abbreviations: HCT, hematocrit; RBC, red blood cell; PC, platelet count; MPV, mean platelet volume; P-LCR, platelet large cell ratio; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLM, PC to MPV ratio.

a Values are expressed as Median (IQR).

b Comparison between HELLP and sever.

c Comparison between severe and mild.

d Comparison between mild and HELLP.

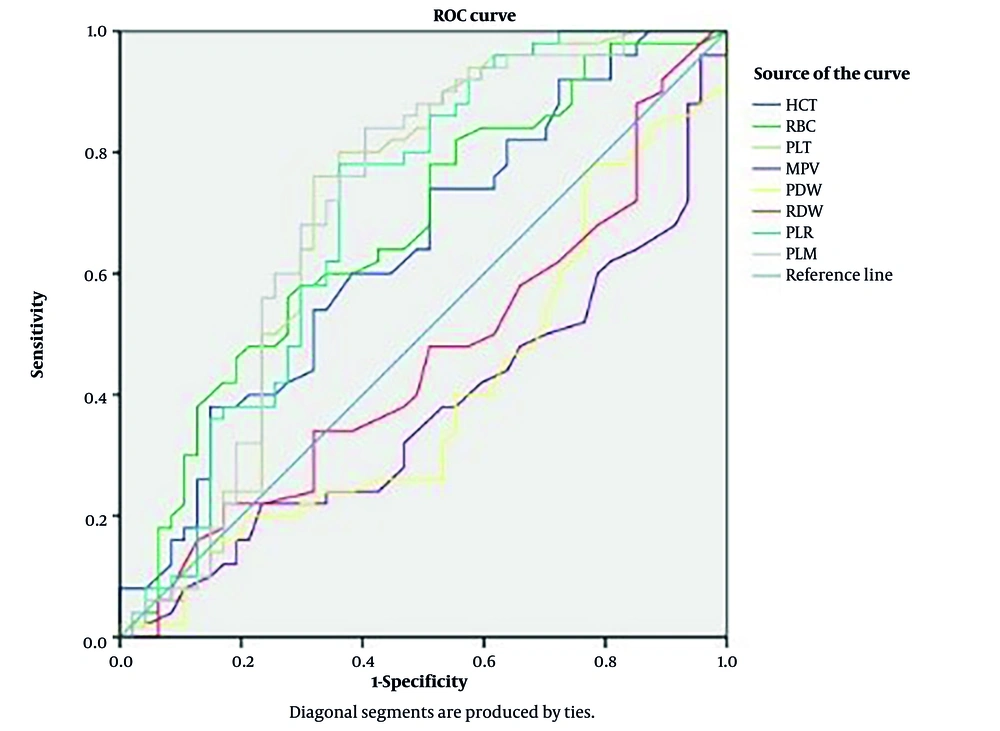

The area under the curve (AUC) was obtained using sensitivity and specificity estimates for various variable cut-offs. The diagnostic value was also measured independently for the HCT, RBC, PC, MPV, PDW, RDW, PLR, and PLM (Table 4). The parameter with the highest AUC is considered the best (16). The AUC for PC, PLR, and PLM were judged regular; however, the AUC for the other variables was not (Table 4, Figure 1).

| Parameters | AUC | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR- | Parameters Classification According to AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCT (%) | 0.637 | 36.3 | 62 | 53 | 54 | 62 | 1.3 | 0.7 | Not good |

| RBC (× 106/µL) | 0.670 | 4.18 | 66 | 51 | 80 | 66 | 1.3 | 0.67 | Not good |

| PC (× 103/µL) | 0.702 | 162.500 | 82 | 55 | 56 | 82 | 1.8 | 0.33 | Regular |

| MPV (fL) | 0.372 | 9.85 | 60 | 21 | 20.4 | 60 | 0.76 | 1.9 | Not good |

| PDW (fL) | 0.399 | 13.55 | 42 | 38 | 36.7 | 42 | 0.67 | 1.5 | Not good |

| RDW (%) | 0.457 | 13.85 | 48 | 49 | 48 | 48 | 0.9 | 1.1 | Not good |

| PLR | 0.701 | 72.67 | 78 | 64 | 64.6 | 78 | 2.2 | 0.3 | Regular |

| PLM | 0.707 | 15.25 | 84 | 60 | 61.2 | 84 | 2.1 | 0.27 | Regular |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; HCT, hematocrit; RBC, red blood cell; PC, platelet count; MPV, mean platelet volume; PDW, platelet distribution width; RDW, red blood cell distribution width; PLR, platelet to lymphocyte ratio; PLM, PC to MPV ratio.

a Values are expressed as percentage.

5. Discussion

One of the most important obstetric tasks is to identify pregnant women who are at high risk of PE. Furthermore, the concept of sensitive and specific biomarkers would allow for not only the identification of individuals at risk of PE but also for attentive monitoring, correct PE diagnosis, and timely intervention during pregnancy.

In the present study, gestational age was significantly higher in women with PE, which aligns with the results of the AlSheeha et al. study (16). Following the present results, previous studies have demonstrated lower PC, PLR, and PLM in preeclamptic women compared to the control group (16, 17). Some researchers showed higher values of MPV in preeclamptic women, which is consistent with our results (18-20). Dogan et al. (17) also reported significantly higher MPV in women with PE than in the control group, which is in accordance with the results of this study.

Comparison of hematological indices in patients with PE showed significant findings. In this study, MPV, PDW, and RDW were decreased in the affected group, while HCT, RBC, PC, PLR, and PLM were increased. Several studies have explored the role of PLR and other hematologic indices in PE. Contrary to some expectations, Yavuzcan et al. found no significant difference in PLR between women with sPE and healthy controls, suggesting that PLR may not be a reliable standalone marker of severity (21). On the other hand, Jaremo et al. observed increased MPV in preeclamptic patients, indicating platelet activation and supporting the idea of vascular involvement in the disease (19). Another study by Yilmaz et al. (22) reported that RDW levels were significantly higher in sPE compared to mild cases, linking this marker to oxidative stress and systemic inflammation. In contrast, another study found no significant change in RDW, indicating variability in findings across different populations and study designs (23).

The ROC curve, an established method for studying biomarker accuracy, was employed to help understand our data. Additionally, the deflection point inside the ROC curve is the ideal cut-off point for variable classification in logistic models. The AUC of ROC can be utilized to calculate the test efficiency (or overall accuracy). Medronho defined AUC in terms of diagnostic quality, and this score (stated in terms of 'Excellent, Good, Normal, and Bad') is used to evaluate the quality of the evaluated parameters (24). Our analysis in this study shows that PC and PLR had consistent diagnostic significance. Freitas et al. established that all platelet characteristics were of regular diagnostic value, with the exception of plateletcrit (PCT), which was considered to be 'bad' for this purpose (25).

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size, particularly in the mild PE and HELLP groups, may reduce the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Second, being a single-center retrospective study, the results may be affected by selection bias and limited external validity. Third, confounding variables such as coexisting conditions or medication use were not fully controlled. Fourth, the lack of longitudinal follow-up limits the ability to assess changes in platelet indices over time. Finally, no inflammatory or endothelial markers were measured for correlation, which could have strengthened the pathophysiological interpretation.

5.1. Conclusions

The PC, PLR, and PLM appear as good candidates in this context, as they are simple and generally performed methods, with lower costs and greater accessibility in the clinical laboratory. Large-scale prospective research from early pregnancy is required to achieve a definitive conclusion. These findings suggest that routine platelet indices — particularly PLR, PC, and PLM — may serve as supportive tools in the early identification and monitoring of patients at risk for PE, especially in low-resource settings where access to advanced diagnostic tools is limited. Their incorporation into standard antenatal blood panels could help clinicians stratify risk and implement closer surveillance protocols for high-risk pregnancies.