1. Background

Volleyball is one of the most popular sports globally, ranking among the top five international sports, played in 220 countries by more than 800 million athletes. The playing positions include outside hitter, middle blocker, opposite hitter, setter, and libero. The main objective is to send the ball over the net to the opponent’s court while preventing the opposing team from returning it (1).

This sport is characterized by short-duration, high-intensity activities that occur repeatedly during both training sessions and competitions. Such characteristics place considerable stress on the musculoskeletal system and expose volleyball players to a high risk of injury (2). The prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries in volleyball has been reported as 10.7 injuries per 1,000 hours of play (3). The most frequently affected areas include the ankle (33%), knee (20%), lower back (12%), and shoulder (11%), with acute injuries most often occurring in the ankle, while overuse injuries are commonly observed in the shoulder, lower back, and knee (4, 5). In the Iranian population, the prevalence of lower limb injuries among young athletes, including volleyball players (5, 6), is high, negatively impacting both physical and psychological health (7). Additionally, limb asymmetry in functional tests such as the Y-Balance Test can serve as a predictor of sports injuries in volleyball players (5, 6). Overall, the lower limbs are the most frequently involved regions, followed by the upper limbs, trunk, and head. Within the lower limbs, the ankle is the most common site of injury, followed by the knee (8).

Volleyball, with its repetitive jumping, landing, and rotational movements, is considered a demanding sport involving explosive actions that impose substantial mechanical stress on the lower limbs. Consequently, players are at risk of injuries such as ankle sprains, knee injuries, and overuse-related disorders (4, 8, 9). These injuries may lead to absences from training and competition, resulting in negative consequences for both athletes and teams (7, 10). Moreover, sports injuries impose significant economic burdens on society, including treatment and hospitalization costs, as well as indirect losses related to missed athletic activity (11, 12).

Therefore, effective preventive measures are essential not only to reduce the prevalence of injuries but also to minimize the associated costs. In this regard, according to van Mechelen et al. “sequence of prevention” model, knowledge of injury incidence, risk factors, and mechanisms is necessary for designing appropriate preventive interventions (13). Accordingly, during the pre-season period, coaches and sports medicine professionals employ various functional performance tests to screen athletes and identify those at higher risk of injury (10, 14). Once high-risk athletes are identified, individualized corrective exercise programs can be developed to address specific functional deficits (15). The primary purpose of screening is, therefore, the early identification of risk factors and the timely implementation of interventions to reduce future injury incidence, minimize lost training time, and prevent aggravation of injuries.

Among the most common screening tools are the Functional Movement Screen, Y-Balance Test, and Tuck Jump Assessment (TJA). Each test assesses specific aspects of neuromuscular control, balance, and lower limb stability. Compared with the Functional Movement Screen and the Y-Balance Test, the TJA provides a more dynamic and sport-specific assessment that reflects the repeated jumping and landing patterns seen in volleyball (16, 17). Poor performance on this test may indicate deficits in strength, balance, or neuromuscular control, all of which are recognized risk factors for injury (18, 19).

Empirical evidence across various sports supports the potential of the TJA in identifying athletes at risk of injury (15, 20, 21). For example, it has been demonstrated that the TJA shows higher sensitivity than other jump-based assessments for detecting knee valgus, making it a valuable tool for injury risk screening (22). However, some studies report limited predictive power of the test, indicating the need for further research across different sports and populations (22). Despite the frequent occurrence of lower limb injuries in volleyball and the recognized importance of functional screening, there is limited evidence regarding the validity of the TJA in predicting injury risk among volleyball players, particularly within the Iranian athletic population. Most available studies have focused on other sports or athletes from Western countries, limiting the generalizability of existing findings (23, 24).

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the prevalence of lower extremity injuries among volleyball players and to evaluate the predictive value of the TJA in identifying athletes at risk of injury. By addressing this research gap, the study seeks to provide evidence-based guidance for injury prevention strategies in volleyball. This study primarily sought to determine the prevalence of lower extremity injuries among volleyball players. A secondary objective was to evaluate the predictive value of the TJA in identifying athletes at risk of injury.

3. Methods

The present descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in the second half of 2024 in Shahroud, Iran, including 139 male and female volleyball players aged 8 to 25 years. Participants were selected through convenience sampling based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included: Age between 8 and 25 years, regular participation in volleyball training (at least three sessions per week with a total duration of 180 minutes), a minimum of one year of playing experience, good general health according to the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire, absence of injury or physical pain at the time of participation, and willingness to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included participation in other research projects, a history of major joint surgery or replacement, unwillingness to complete the questionnaire, or attendance below 80% of training sessions. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Technology (IR.SHAHROODUT.REC.1403.028), and all procedures followed the STROBE checklist for cross-sectional studies.

A structured, researcher-designed questionnaire was used to collect demographic data (age, sex, height, and weight), training information (experience, number of weekly sessions, session duration, and participation in other sports), and injury history within the past six months. To minimize recall bias, all reported injuries were verified by the players’ coaches, who confirmed each case based on training and competition records. Injury was defined as any physical complaint resulting from participation in volleyball that restricted the athlete from fully participating in subsequent training or competition, in line with International Olympic Committee consensus definitions (25, 26).

The TJA was performed to assess functional performance deficits. This test requires athletes to execute repeated tuck jumps in place for 10 seconds at maximum speed and intensity. Prior to the test, participants received standardized instructions on how to bring their knees toward the chest and land in the same spot. They were instructed to use a toe-to-heel landing technique and minimize ground contact time, maintaining the same landing position after each jump. Performance was evaluated using a 10-item standardized checklist, as previously described by Read et al. (16). A landing deficit was confirmed if the participant was unable to maintain proper movement technique throughout the 10-second period.

To ensure accuracy, the test was recorded using two high-resolution video cameras (Xiaomi Mi 10T Pro) positioned in the frontal and sagittal planes at a height of 70 cm and a distance of 5 meters from the center of the capture area, with a sampling rate of 60 Hz. Participants wore sports shorts to allow clear visualization of knee movement. Each of the ten performance criteria was analyzed, and if a deficit was observed in two or more repetitions, it was recorded. A composite score representing the total number of deficits was calculated for each athlete, with higher scores indicating greater performance deficiencies. The maximum possible score was 10, suggesting that the player required further technical training. All evaluations were conducted by a single trained assessor to avoid inter-rater error, and intra-rater reliability was confirmed in a pilot analysis (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.91).

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage) were used to summarize the data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed normality. Between-group comparisons were performed using independent t-tests and chi-square tests, and binary logistic regression analysis was applied to identify predictors of injury. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

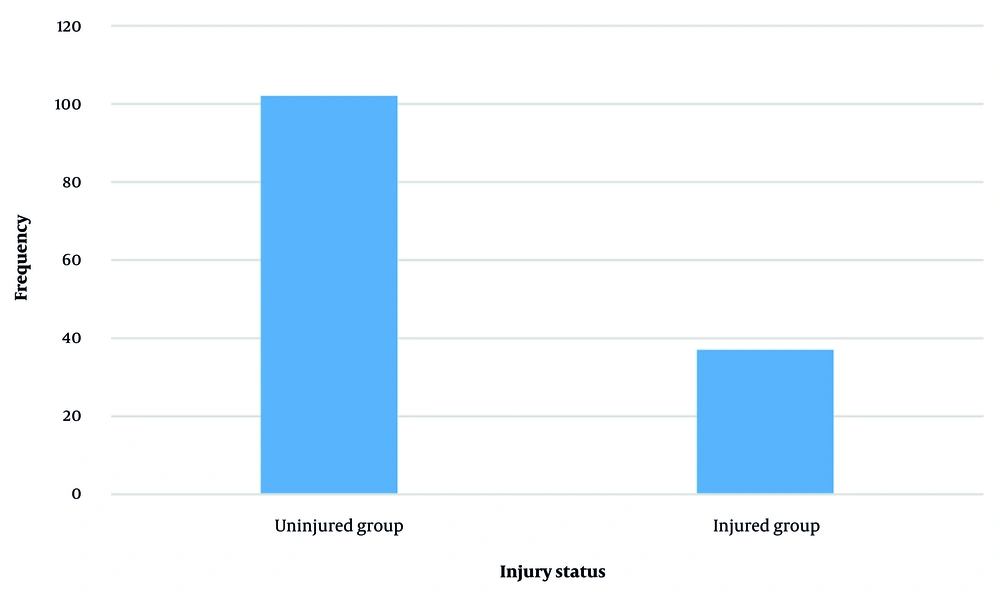

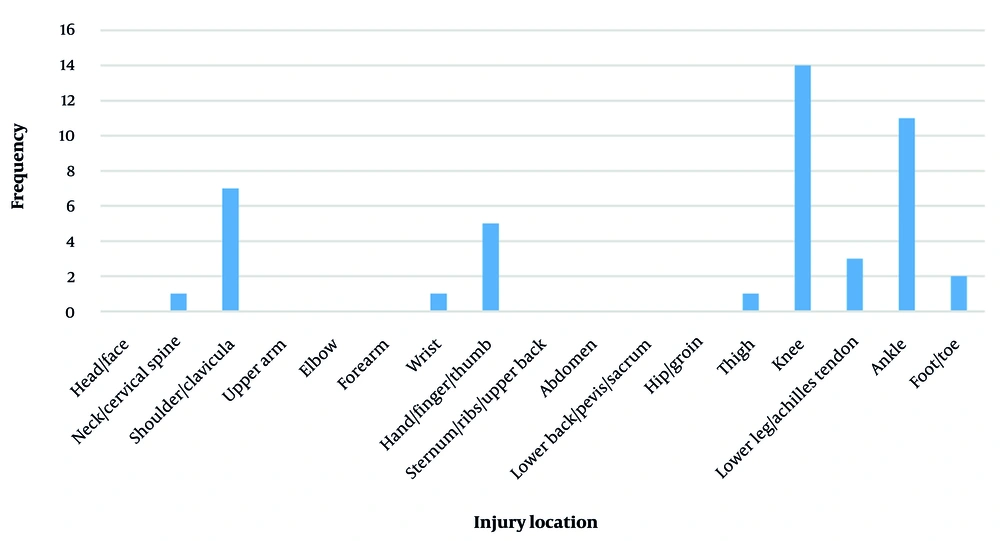

The results of the study indicated that among the 139 volleyball players who participated, 37 (27%) had experienced at least one sports injury in the past six months, while 102 (73%) reported no injury history. A total of 45 injuries were documented, with the majority affecting the lower limbs. The most common injury sites were the knee (31%), ankle (24%), shoulder and clavicle (15%), fingers (11%), and calf and thigh (9%), while injuries to the head, spine, and wrist were relatively rare (3%). These distributions are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Comparative analysis between the injured and uninjured groups indicated that age, height, weight, training experience, and participation in other sports were significantly associated with injury occurrence, whereas gender, weekly training sessions, and TJA scores were not significant predictors (Table 1). The mean age of the injured group (16.5 ± 3.6 years) was significantly higher than that of the uninjured group (14.2 ± 2.7 years) (t = 4.045, P < 0.001). Each additional year of age increased the likelihood of injury by 27% [odds ratio = 1.27 (95% confidence interval: 1.11 - 1.46); P < 0.001]. Injured players were also taller (173 ± 15.4 cm vs. 164 ± 14.1 cm; t = 3.037, P < 0.001), with each 1 cm increase in height associated with a 4% higher risk of injury [odds ratio = 1.04 (95% confidence interval: 1.01 - 1.07); P = 0.004]. Similarly, higher body weight significantly increased injury risk (63.2 ± 13.7 kg vs. 54.8 ± 14.5 kg; t = 3.057, P = 0.003), corresponding to odds ratio = 1.04 (95% confidence interval: 1.01 - 1.07); P = 0.004. Sports experience was also a strong predictor of injury, as injured athletes had substantially more training months (66.7 ± 53.2 vs. 37.8 ± 29.8; t = 4.019, P < 0.001), indicating that each additional month of experience increased injury likelihood by approximately 2% [odds ratio = 1.02 (95% confidence interval: 1.01 - 1.03); P < 0.001]. In addition, participation in other sports significantly elevated injury risk [odds ratio = 2.71 (95% confidence interval: 1.15 - 6.35); P = 0.02], suggesting that multi-sport athletes were about 2.7 times more likely to experience injury.

| Variables | Total (n = 139) | Uninjured (n = 102) | Injured (n = 37) | t | P-Value | Odd Ratio (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.15 | 0.8 | 0.85 (0.37 - 1.96) | 0.7 | |||

| Male | 98 (70.5) | 71 (69.6) | 27 (73) | ||||

| Female | 41 (29.5) | 31 (30.4) | 10 (27) | ||||

| Age (y) | 14.8 ± 3.1 | 14.2 ± 2.7 | 16.5 ± 3.6 | 4.04 | < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.11 - 1.46) | < 0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 166.8 ± 14.9 | 164.6 ± 14.1 | 173 ± 15.4 | 3.3 | < 0.001 | 1.04 (1.01 - 1.07) | 0.004 |

| Weight (kg) | 57 ± 14.7 | 54.8 ± 14.5 | 63.2 ± 13.7 | 3.05 | 0.003 | 1.04 (1.01 - 1.07) | 0.004 |

| Sporting experience (mo) | 45.5 ± 39.4 | 37.8 ± 29.8 | 66.7 ± 53.2 | 4.01 | < 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01 - 1.03) | < 0.001 |

| Participation in other sports | 0.03 | 5.47 | 2.71 (1.15 - 6.35) | 0.02 | |||

| Yes | 30 (21.6) | 17 (16.7) | 13 (35.1) | ||||

| No | 109 (78.4) | 85 (83.3) | 24 (64.9) | ||||

| Training sessions per week [median (interquartile)] | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | -1.59 | 0.11 | 1.26 (0.95 - 1.66) | 0.1 |

| TJA (total score) | 4.3 ± 1.8 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | -1.57 | 0.11 | 0.84 (0.68 - 1.04) | 0.1 |

Abbreviation: TJA, Tuck Jump Assessment.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

No significant difference was found between the two groups in terms of the number of weekly training sessions (3 ± 2 vs. 2 ± 1; P = 0.11), nor did this variable significantly predict injury occurrence [odds ratio = 1.26 (95% confidence interval: 0.95 - 1.66); P = 0.10]. Likewise, the mean TJA score did not significantly differ between the injured (4.8 ± 1.9) and uninjured (4.4 ± 1.6) athletes (t = 1.57, P = 0.12), and this variable was not a significant predictor in the regression model [odds ratio = 0.84 (95% confidence interval: 0.68 - 1.04); P = 0.12].

5. Discussion

The present study investigated the prevalence of lower extremity injuries among volleyball players and assessed whether the TJA could predict injury risk. The results indicated that the overall injury prevalence was 27%, with the knee, ankle, and shoulder being the most commonly affected areas. However, contrary to expectations, TJA scores did not significantly differ between injured and uninjured athletes and did not predict injury occurrence. Instead, factors such as age, height, weight, sports experience, and participation in other sports were significantly associated with injury risk.

These findings suggest that the TJA, when used in isolation, may lack sufficient sensitivity to detect subtle movement deficiencies related to injury risk in volleyball players. Volleyball-specific movement patterns, such as repeated jumping, spiking, and blocking, differ from those in other sports (e.g., soccer or basketball), where the TJA has shown stronger predictive validity (16, 26). In this context, differences in jumping technique, landing surface, and sport-specific motor demands may contribute to the limited predictive capacity of the TJA. Moreover, as noted by Hoog et al., the test’s ability to predict injury may be influenced by the evaluator’s experience, scoring consistency, and the use of two-dimensional rather than three-dimensional motion analysis, all of which could affect sensitivity and accuracy (24). Additionally, although a multivariable logistic regression model was performed, the relatively small number of injured athletes (n = 37) may have reduced the model’s statistical power and stability. Therefore, the observed odds ratios should be interpreted cautiously, and future studies with larger samples are needed to confirm these associations.

The results align with those of Hoogh et al., who also found that TJA scores were not significantly associated with injury risk in collegiate female athletes (24), but they contrast with the findings of Myer et al. and Brumitt et al., who reported significant associations between TJA performance and subsequent injury risk (21, 26). One possible explanation is that, unlike the prospective designs used in previous studies, the present study’s cross-sectional approach limits the ability to establish temporal or causal relationships. Injuries were self-reported retrospectively, and test performance was assessed at a single time point, making it difficult to determine whether poor TJA performance preceded or resulted from injury.

Additionally, the influence of confounding variables such as age, anthropometric characteristics, training load, and multi-sport participation likely contributed to the observed outcomes. Older and more experienced players, who trained longer and participated in multiple sports, exhibited a higher risk of injury. This trend may reflect cumulative musculoskeletal stress and fatigue over time rather than immediate biomechanical deficits. Previous studies have similarly demonstrated that greater sports experience and multi-sport involvement increase chronic stress exposure and, consequently, injury risk (27-29). Furthermore, the limited geographic scope of this study (Shahroud city) may reflect specific coaching methods, training environments, and cultural factors that influence both injury patterns and movement quality, limiting generalizability to broader volleyball populations.

From a practical perspective, these findings highlight the need for a multifactorial approach to injury screening. Coaches and sports medicine practitioners should not rely solely on the TJA for identifying at-risk athletes but should integrate it with other functional assessments such as the Y-Balance Test or Closed Kinetic Chain Upper Extremity Stability Test. Such combined assessments may better capture neuromuscular control, dynamic balance, and sport-specific movement quality. Furthermore, individualized screening that considers personal characteristics — such as age, height, weight, and training history — may provide a more accurate risk profile.

Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the present study precludes causal inference. Future longitudinal and experimental studies using three-dimensional motion capture, electromyographic analysis, and prospective tracking of injury incidence are recommended to clarify the causal relationships between functional movement patterns and injury risk in volleyball players.

5.1. Limitations

The present study is subject to several limitations that warrant caution in interpreting the results. Its cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences, as data collection at a single time point cannot discern whether impaired movement quality predated or resulted from injury. Self-reported injury data, despite coach verification, remain vulnerable to recall bias and potential underreporting or misclassification of minor injuries. The TJA relied on a single rater, which, although yielding high intra-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.91) and minimizing inter-rater variability, may introduce subjective bias. The sample was restricted to volleyball players from Shahroud city, limiting generalizability to athletes from diverse regions or higher competitive levels. Future research should therefore incorporate broader, multilevel cohorts to strengthen external validity. Despite these constraints, the study offers meaningful preliminary insights into the interplay of anthropometric, training, and functional factors in volleyball injury risk.

5.2. Future Research

The present study revealed that anthropometric factors (age, height, weight) and training experience significantly predicted injury risk in volleyball players, whereas the TJA score alone showed no significant association, indicating that isolated jumping assessments are insufficient for accurate prediction in this population. Injury risk appears driven by a multifactorial interplay of individual characteristics rather than single functional measures; therefore, future research should adopt prospective or longitudinal designs to establish causality between movement patterns and injury, integrate multiple functional tests (e.g., TJA, Y-Balance Test, and Closed Kinetic Chain Upper Extremity Stability Test) for enhanced predictive validity, and control for confounding variables including core stability, muscle fatigue, sleep quality, nutrition, and psychological stress. Given the wide age range potentially masking maturation-related differences, stratification by developmental stage is recommended. Practically, coaches and clinicians should monitor training load and recovery, combine the TJA with comprehensive biomechanical screening, and evaluate preventive exercise programs tailored to identified risk profiles to effectively reduce injury rates in volleyball athletes.