1. Background

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is consistently ranked among the most prevalent mental health conditions in the general population, with its onset frequently occurring during early to middle adolescence (1). Lifetime prevalence rates are estimated at approximately 8 - 9% among adolescents globally, underscoring the disorder's widespread impact during this critical developmental stage. Adolescence amplifies SAD risks due to heightened sensitivity to social evaluation amid rapid hormonal shifts, intensified peer dynamics, and the consolidation of self-identity, which can transform transient fears into entrenched patterns of avoidance and distress (2). The disorder is defined by an intense, persistent fear of social or performance situations in which the individual is exposed to potential scrutiny by others (3). Untreated, SAD in adolescents can lead to profound long-term functional impairment, including chronic peer rejection, academic underachievement, social isolation, and an elevated risk for developing secondary disorders such as Major Depressive Disorder and substance use problems (4). Therefore, targeted and highly effective psychological interventions are imperative for mitigating the pervasive social and developmental costs associated with SAD in this vulnerable group.

A pivotal cognitive model explaining the maintenance of SAD is the Metacognitive Model, which shifts focus from the content of anxious thoughts to beliefs about the thoughts and emotional processes themselves (5). These metacognitive beliefs about emotions — commonly referred to as metaemotions and defined here as individuals' attitudes, evaluations, and beliefs regarding their own emotional experiences (6), which are the focus of this study, include two critical and interconnected dimensions: Positive meta-emotions (beliefs reflecting compassion toward and interest in one's emotions, fostering adaptive engagement) and negative metaemotions (beliefs involving anger, shame, suppression, or perceived uncontrollability of emotions, promoting avoidance and distress). In adolescents with SAD, these maladaptive metacognitive beliefs about emotions drive the pervasive cycle of excessive self-focused attention, worry, and post-event rumination, preventing the individual from fully engaging in social situations and obtaining necessary reality-testing information (7). Effectively challenging and restructuring these specific emotional and cognitive processes is a fundamental goal in successful anxiety treatment (8).

In addition to the cognitive domain, social self-efficacy plays a direct and critical role in the expression and maintenance of SAD. Derived from Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory, social self-efficacy refers to an individual's belief in their capability to successfully execute the behaviors required to produce desired social outcomes (9). Adolescents suffering from SAD typically exhibit significantly lower social self-efficacy, perceiving themselves as incapable of handling challenging social interactions, expressing opinions, or managing negative feedback effectively (10). This deficiency acts as a central mediating factor, leading directly to the hallmark feature of the disorder: Avoidance behavior (11). By pre-empting social engagement, avoidance prevents the accrual of successful social experiences that could naturally bolster self-efficacy. Consequently, therapeutic approaches that directly enhance social self-efficacy are vital for promoting sustainable behavioral change and confidence (12).

Previous research has established the efficacy of interventions targeting these mechanisms in adolescent SAD. For instance, mindfulness-based approaches, including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), have shown promise in reducing anxiety symptoms and maladaptive metacognitions through enhanced emotional regulation (13-15). Similarly, exposure-based therapies, particularly those augmented by virtual reality (VR), have demonstrated robust reductions in avoidance and improvements in social functioning via simulated real-world practice (16-19). A limited number of comparative studies exist, primarily in adult populations; for example, investigations comparing VR exposure to mindfulness-acceptance therapies have reported VR's advantages in symptom reduction and engagement for social anxiety, though often without adolescent-specific adaptations or focus on intermediate outcomes like self-efficacy (20).

One highly regarded therapeutic approach is MBCT, an established, evidence-based intervention that integrates techniques from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with mindfulness meditation practices (21). The core therapeutic mechanism of MBCT is the development of decentering, which enables individuals to observe their thoughts, feelings, and metacognitive processes as transient mental events rather than identifying with them as literal reality (22). For adolescents with SAD, MBCT offers a powerful tool to interrupt the automatic loop of anxious worrying and rumination, thereby reducing the influence of rigid negative metacognitive beliefs about emotions (13). A growing body of research supports the efficacy of MBCT in reducing overall anxiety symptoms and improving emotional regulation, with several studies specifically highlighting its positive effects on reducing maladaptive metacognitive beliefs in both adult and adolescent anxiety populations (14, 15).

In contrast, virtual reality-based worry exposure therapy (VR-WET) represents a cutting-edge technological advancement of the gold-standard exposure treatment (23). Virtual reality environments allow for the creation of controlled, highly realistic, and customizable simulations of feared social or worry-eliciting situations that might be impractical or unethical to replicate in real-life settings (24). The therapeutic mechanism of VR-WET relies on habituation and extinction learning, enabling participants to repeatedly confront feared social stimuli in a safe and supportive context until the associated anxiety response diminishes (16). This method is particularly effective for SAD, as the high sense of control and systematic nature of VR exposure enhances treatment engagement and directly challenges the avoidance behaviors that maintain the disorder (17). Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that VR-based exposure is highly effective in reducing SAD symptoms and simultaneously improving self-reported social self-efficacy through successful behavioral performance within the virtual environment (18, 19).

Despite these advances, a critical research gap persists: No studies have directly compared MBCT and VR-WET in adolescents with SAD, particularly regarding their relative impacts on theory-driven mechanisms such as metacognitive beliefs about emotions and social self-efficacy. Prior comparisons have largely overlooked adolescent developmental contexts, focused on broad symptom outcomes rather than these specific mediators, or examined mindfulness variants without VR-WET's worry-focused exposure hierarchy. This omission limits evidence-based personalization of treatments, as adolescents may respond differentially to cognitive decentering versus behavioral mastery via immersive simulations. Addressing this gap is urgent to optimize interventions that disrupt SAD's maintenance cycles early, preventing lifelong sequelae.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study was conducted to critically compare the effectiveness of MBCT and VR-WET on the positive and negative metacognition subscales and social self-efficacy in adolescents diagnosed with SAD.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

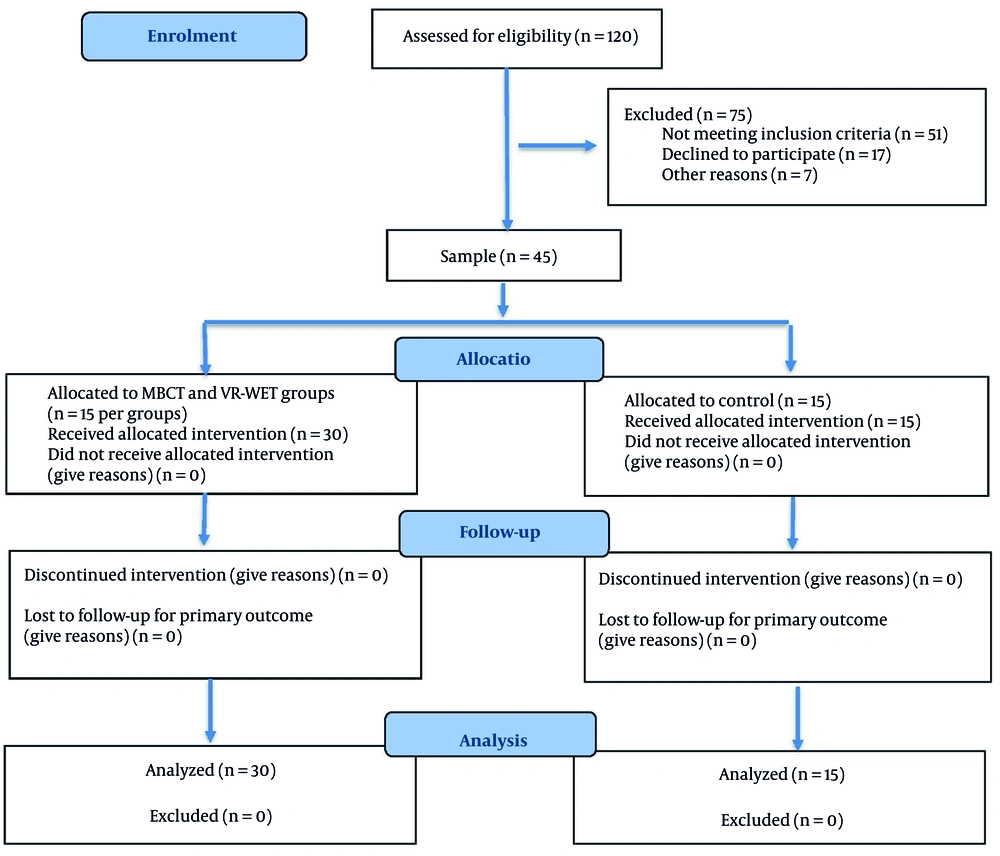

This randomized controlled trial utilized a clinical trial design with pre-test, post-test, and three-month follow-up assessments, including a waiting-list control group. The statistical population consisted of all adolescents (aged 15 - 18 years) diagnosed with SAD who were referred to specialized counseling centers in Ahvaz during the year 2024. Participants were recruited via referrals from school counselors and pediatric clinics, with initial screening of 120 adolescents; eligibility assessments yielded 75 candidates, of whom 45 met criteria and were enrolled (Figure 1). A purposive sample of 45 adolescents was selected from this population. Inclusion criteria for participation were: A definitive diagnosis of SAD confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) (based on DSM-5 criteria) conducted by a licensed psychologist, and achieving a minimum score of ≥ 50 on the Social Anxiety Scale. Exclusion criteria included the presence of comorbid major clinical disorders (e.g., severe depression, psychotic disorders), any chronic physical or neurological illness, concurrent participation in other psychological treatments, or absence from more than two treatment sessions. Sample size was justified via a priori power analysis using G*Power software (version 3.1), which indicated that n = 15 per group provided 80% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed) to detect medium effect sizes (f = 0.25) in repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the primary interaction term. The selected participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups (n = 15 each): The MBCT group, the VR-WET group, and the waiting-list control group, using computer-generated random numbers stratified by age and gender; allocation was concealed via sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes opened only at enrollment. All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed consent, and all ethical considerations were approved by the university’s institutional ethics committee.

3.2. Procedure and Intervention Protocols

Following the administration of the pre-test, the intervention groups commenced their respective protocols. Both the MBCT and VR-WET protocols comprised 8 sessions, each lasting 90 minutes, and were conducted twice per week. The control group received no intervention during this period but was offered treatment upon study completion. Post-test measurements were collected immediately after the final treatment session, and the three-month follow-up assessment was conducted three months later. All interventions were delivered by two licensed and experienced clinical psychologists in a standardized manner.

3.2.1. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

The MBCT protocol was adapted from the manual developed by Segal et al. (25) for an adolescent population, focusing on the development of decentering and present-moment awareness. The key elements and session focus are summarized in Table 1.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Establish confidentiality and group guidelines, participant introductions, mindful raisin-eating exercise, 45-minute body scan practice. Homework: Daily body scan and mindful engagement in one routine activity (e.g., washing, eating, brushing teeth) |

| 2 | Review homework, conduct thoughts and feelings exercise to enhance awareness. Homework: Record pleasant events daily |

| 3 | Review homework, 30 - 40-minute sitting meditation, mindful walking practice. Homework: Daily mindful walking, three 3-minute breathing space exercises, and record unpleasant events |

| 4 | Review homework, seeing/hearing meditation to enhance sensory awareness, sitting meditation practice. Homework: Daily sitting meditation and three 3-minute breathing space exercises |

| 5 | Conduct guided sitting meditation to deepen mindfulness. Homework: Practice guided sitting meditation daily |

| 6 | Conduct visualization-based sitting meditation, practice ambiguous scenarios to address uncertainty. Homework: Practice shorter guided meditations (minimum 40 minutes) and three 3-minute breathing space exercises daily |

| 7 | Conduct sitting meditation, discuss self-directed practice and links between mood and activity, address relapse indicators. Homework: Self-directed practice, three 3-minute breathing space exercises daily (especially during stress), and plan for relapse prevention |

| 8 | Conduct body scan, review homework, facilitate reflection and feedback, conclude sessions, and administer post-test |

3.2.2. Virtual Reality-Based Worry Exposure Therapy

The VR-WET protocol was based on standard exposure therapy principles, utilizing Oculus Quest 2 Head-Mounted Display (HMD) technology to simulate social situations. The intervention focused on habituation and systematic exposure to hierarchical, fear-inducing social scenarios (23). Table 2 outlines the key stages of this protocol.

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Introduce VR technology, provide psychoeducation, expose participants to a public setting (e.g., store) with continuous attention from others to initiate low-intensity exposure |

| 2 | Continue exposure in a public setting (e.g., store), reinforcing habituation to being observed by others |

| 3 | Expose participants to a large party setting, requiring them to read a poem or text using a microphone while being observed by attendees. |

| 4 | Continue exposure in a large party setting, practicing reading a poem or text with a microphone to deepen habituation |

| 5 | Expose participants to a formal administrative meeting, presenting academic or professional content using a microphone and maintaining eye contact with attendees |

| 6 | Continue exposure in a formal administrative meeting, reinforcing presentation skills and eye contact to reduce anxiety |

| 7 | Expose participants to a large seminar, delivering a prepared text using a microphone from a podium while maintaining eye contact with the audience. |

| 8 | Continue seminar exposure, consolidating skills, reinforcing habituation, and practicing eye contact to enhance social confidence |

3.3. Measurement Instruments

3.3.1. Metaemotion Questionnaire

The Metaemotion Questionnaire (MEQ) was developed by Mitmansgruber et al. (26) to assess individuals' beliefs about their own emotions (metacognitive beliefs about emotions). It comprises 28 items and six subscales, which primarily load onto two factors: Negative metaemotion (anger, shame, thought control, suppression) and positive metaemotion (compassion, interest). The positive metaemotion factor score was computed as the sum of items from the compassion and interest subscales (range: 10 - 25); the negative metaemotion factor score as the sum of items from the anger, shame, thought control, and suppression subscales (range: 18 - 60). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all true to 5 = Completely true). Factor total scores for positive and negative dimensions range from 28 to 140 each, with higher scores on the negative factor indicating greater emotional dysfunction. The MEQ demonstrates strong construct validity in prior anxiety research, with factor loadings >0.60 in confirmatory analyses (26), and convergent validity with metacognitive scales (r = 0.55 - 0.72). In previous Farsi language studies, the Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale has typically ranged from 0.75 to 0.90 (27). The reliability coefficient in the current study was highly satisfactory (α = 0.90).

3.3.2. Self-efficacy Scale for Social Situations

The Self-efficacy Scale for Social Situations (SESS) was designed by Gaudiano and Herbert (28) to measure self-efficacy specific to managing threatening social situations. The scale consists of 9 items that assess three subscales: Coping skills self-efficacy, cognitive control self-efficacy, and mental distress self-efficacy. The scoring yields a minimum possible score of 0 and a maximum of 81. Higher scores reflect a greater level of confidence in successfully navigating social challenges. The SESS exhibits good content validity through expert ratings (κ = 0.78) and predictive validity for social avoidance behaviors (r = -0.62; 28). The internal consistency of the SESS in the current study was robust (α = 0.88).

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS software (version 27.0). Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) were used to summarize the data. Normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test; homogeneity of variances via Levene’s test; and sphericity via Mauchly’s test, with Greenhouse-Geisser corrections applied where violated (ε < 0.75). The significance level was set at α = 0.05 for all inferential tests. The primary inferential statistical method used to test the hypotheses and to compare changes in the dependent variables across the three measurement phases (pre-test, post-test, and follow-up) for between the three groups was repeated measures ANOVA, specifically a 3 (group: MBCT, VR-WET, control) × 3 (time: Pre, post, follow-up) mixed-model design to examine main effects of time and group, as well as the time × group interaction. When significant differences were found, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were employed for pairwise comparisons to control for multiple testing.

4. Results

The research involved 45 adolescents aged 15 - 18 years with a confirmed SAD diagnosis. The participants' average age was 16.62 ± 1.73 years. Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for positive metaemotion, negative metaemotion, and social self-efficacy across the three study phases. The intervention groups exhibited changes in mean scores from pre-test to post-test and follow-up, while the control group showed small variations, including a minor increase in social self-efficacy (Δ = 0.07) that was non-significant (P > 0.05).

| Variables and Stages | MBCT | VR-WET | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive metaemotion | |||

| Pre-test | 35.46 ± 3.66 | 35.60 ± 3.99 | 34.53 ± 4.22 |

| Post-test | 43.60 ± 3.50 | 47.33 ± 4.08 | 34.93 ± 4.52 |

| Follow-up | 43.66 ± 3.28 | 47.53 ± 4.17 | 35.13 ± 4.48 |

| Negative metaemotion | |||

| Pre-test | 40.46 ± 3.66 | 41.06 ± 3.95 | 39.40 ± 3.50 |

| Post-test | 32.73 ± 4.00 | 29.33 ± 4.20 | 39.00 ± 3.35 |

| Follow-up | 32.80 ± 4.05 | 29.6 ± 4.03 | 39.06 ± 4.51 |

| Social self-efficacy | |||

| Pre-test | 41.20 ± 4.90 | 41.80 ± 4.16 | 39.66 ± 4.38 |

| Post-test | 50.46 ± 6.01 | 54.60 ± 4.54 | 39.73 ± 4.36 |

| Follow-up | 50.46 ± 5.92 | 54.66 ± 4.59 | 40.00 ± 4.44 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; VR-WET, virtual reality–based worry exposure therapy; SD, standard error.

Prior to ANOVA, data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for each variable across groups and time points (all P > 0.05). Homogeneity of variances was confirmed via Levene’s test (all P > 0.05). Mauchly’s test of sphericity was significant for negative metaemotion (χ² = 12.45, P = 0.002, ε = 0.855) and social self-efficacy (χ² = 18.32, P < 0.001, ε = 0.560); thus, Greenhouse-Geisser corrected degrees of freedom were applied for these variables. Sphericity was assumed for positive metaemotion (χ² = 3.21, P = 0.201). Table 4 summarizes the repeated measures ANOVA results, indicating significant main effects of time and group, as well as time × group interactions for all variables (all P < 0.001). The partial eta squared (ηp²) values ranged from 0.45 to 0.78, reflecting large effect sizes.

| Variables and Source | SS | df | MS | F | P-Value | ηp² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive metaemotion | ||||||

| Time | 1401.37 | 2 | 700.68 | 1484.64 | 0.001 | 0.77 |

| Time × Group | 668.97 | 4 | 167.24 | 354.36 | 0.001 | 0.74 |

| Group | 1762.84 | 2 | 881.42 | 38.94 | 0.001 | 0.52 |

| Negative metaemotion | ||||||

| Time | 1289.65 | 1.71 | 754.02 | 2678.52 | 0.001 | 0.78 |

| Group | 650.78 | 3.42 | 190.24 | 675.81 | 0.001 | 0.77 |

| Time × Group | 787.61 | 2 | 393.80 | 29.15 | 0.001 | 0.45 |

| Social self-efficacy | ||||||

| Time | 1657.91 | 1.12 | 1473.46 | 862.73 | 0.001 | 0.75 |

| Group | 848.71 | 2.24 | 377.14 | 220.82 | 0.001 | 0.71 |

| Time × Group | 2665.64 | 2 | 1132.82 | 43.02 | 0.001 | 0.57 |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; MS, mean square; df, degrees of freedom; F, F-statistic; η2, Eta-squared.

Table 5 presents Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons, revealing no significant pre-test differences between groups (all P > 0.05). At post-test and follow-up, VR-WET significantly outperformed MBCT in positive metaemotion, negative metaemotion, and social self-efficacy (all P < 0.05). Both interventions significantly outperformed the control group (all P < 0.001), with VR-WET showing larger mean differences.

| Variables, Group Comparison and Stage | Mean Difference | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Positive metaemotion | ||

| MBCT, VR-WET | ||

| Pre-test | 0.13 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 3.73 | 0.040 |

| Follow-up | 3.86 | 0.031 |

| MBCT, control | ||

| Pre-test | 0.93 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 8.66 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 8.53 | 0.001 |

| VR-WET, control | ||

| Pre-test | 1.06 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 12.40 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 12.40 | 0.001 |

| Negative metaemotion | ||

| MBCT, VR-WET | ||

| Pre-test | 0.60 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 3.40 | 0.032 |

| Follow-up | 3.20 | 0.040 |

| MBCT, control | ||

| Pre-test | 1.06 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 6.26 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 6.26 | 0.001 |

| VR-WET, control | ||

| Pre-test | 1.66 | 0.672 |

| Post-test | 9.66 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 9.46 | 0.001 |

| Social self-efficacy | ||

| MBCT, VR-WET | ||

| Pre-test | 0.60 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 4.13 | 0.023 |

| Follow-up | 4.20 | 0.011 |

| MBCT, control | ||

| Pre-test | 1.53 | 0.999 |

| Post-test | 10.73 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 10.64 | 0.001 |

| VR-WET, control | ||

| Pre-test | 2.13 | 0.604 |

| Post-test | 14.86 | 0.001 |

| Follow-up | 14.66 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: MBCT, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy; VR-WET, virtual reality-based worry exposure therapy.

5. Discussion

The present study compared the efficacy of MBCT and VR-WET in adolescents aged 15 - 18 years with SAD, focusing on metacognitive beliefs about emotions (positive and negative subscales) and social self-efficacy. Consistent with prior evidence on third-wave cognitive-behavioral and technology-enhanced exposure interventions, both treatments yielded sustained improvements relative to a waiting-list control, underscoring their utility in disrupting SAD maintenance cycles (15, 24).

A closer examination of between-group differences highlighted VR-WET's advantages over MBCT across outcomes, a pattern that aligns with theoretical models emphasizing behavioral mastery as a primary driver of self-efficacy gains. Specifically, VR-WET's immersive simulations facilitate enactive mastery experiences — repeated, graduated successes in feared scenarios — that directly challenge avoidance and recalibrate efficacy beliefs more potently than MBCT's metacognitive decentering, which primarily fosters observational distance from thoughts (12, 17). This integration of Bandura's social cognitive framework with extinction principles explains VR-WET's edge: Virtual successes not only extinguish conditioned anxiety but also accumulate "efficacy-building" evidence, accelerating shifts in metacognitive beliefs about emotional controllability and adaptive engagement (9, 16). In contrast, MBCT's effectiveness in mitigating negative metacognitive beliefs about emotions — such as perceived uncontrollability — stems from decentering, which promotes non-reactive awareness of worry as transient rather than veridical. These gains mirror findings from Aydın et al., where mindfulness interventions reduced metacognitive rigidity in anxiety disorders via similar awareness mechanisms, though with more modest effects on behavioral confidence (29).

The observed superiority of VR-WET echoes and extends comparative trials in adolescent SAD. For example, Razzaghi et al. reported VR exposure outperforming MBCT in enhancing social engagement and fear of negative evaluation, attributing this to VR's immersive extinction context (20). Methodological parallels include equivalent session durations (8 weekly sessions), adolescent samples (n ≈ 40 - 50), and focus on exposure hierarchies, alongside shared use of self-report outcomes like the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale. However, differences temper direct equivalence: Razzaghi et al. emphasized broad symptoms without dissecting metacognitive subscales or self-efficacy mediators, and employed non-random allocation, potentially inflating VR effects; our randomized, blinded design with follow-up assessments provides stronger causal evidence for sustained mechanism-specific changes (20). Broader literature reinforces this, as meta-analyses indicate VR exposure yields larger effect sizes than mindfulness for SAD behavioral outcomes, particularly in youth where engagement barriers are high (17).

Clinically, these results position VR-WET as a frontline option for adolescent SAD when prioritizing rapid self-efficacy enhancement and metacognitive restructuring, especially in settings like Ahvaz where scalable, low-burden interventions are needed. virtual reality's cost-effectiveness — initial hardware investments offset by reduced therapist time and dropout rates — makes it viable for resource-limited regions, though accessibility barriers such as device availability and cultural adaptation for low-SES youth warrant targeted subsidies or mobile VR adaptations (18, 23). Nonetheless, MBCT remains a valuable alternative for clients preferring non-technological approaches or with access constraints.

5.1. Limitations

Limitations temper these insights: Reliance on self-reports risks common method bias, and the Ahvaz-specific sample curtails generalizability to multicultural or non-urban adolescents. Future research should dismantle VR-WET components (e.g., immersion vs. interactivity) via factorial designs and track long-term outcomes (e.g., 12-month functioning) to isolate active ingredients. Hybrid trials integrating MBCT's decentering with VR mastery could further personalize treatments, leveraging machine learning for adaptive protocols.

5.2. Conclusions

This study concludes that both VR-WET and MBCT are effective clinical interventions for improving maladaptive metaemotions (both positive and negative) and enhancing social self-efficacy in adolescents with SAD. Crucially, the findings demonstrate the statistically superior efficacy of VR-WET compared to MBCT across all measured outcomes. This advocates for integrating VR technology into standard exposure protocols as the most potent therapeutic modality for achieving rapid and robust cognitive and behavioral change in this population. Ultimately, these findings advance a precision medicine paradigm for adolescent anxiety, where mechanism-targeted therapies like VR-WET can be matched to profiles of low self-efficacy and rigid metacognitions, fostering resilient social development amid rising global SAD burdens.