1. Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has spread worldwide at a dangerous rate. There are sparse reports of children suffering from COVID-19. Studies have suggested different numbers in incidence: Two percent in the largest series from China, 1.2% in the pediatric cohort from Italy, 4.8% in Korea, and 1.7% in the United States (1). The reason is not clearly understood but may be due to more protective measures for the pediatric group, such as social distancing and community closure. Children can be infected with SARS-CoV-2 as likely as adults but become less symptomatic and develop less severe disease. The reported percentage of children who were either asymptomatic or had mild to moderate disease was 94.1% in the largest series (2). Admission of children to the intensive care unit (ICU) has been reported sparsely. The largest pediatric series showed 5.2% of children with respiratory distress or hypoxia, whereas 0.6% eventually complicated to acute respiratory distress syndrome or progressed to multi-organ failure (3).

The most frequent complaints of children with SARS-CoV-2 are flu-like symptoms such as fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Some cases presented with chest pain, while others have shown only gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Severe forms in infants and children were presented with cold extremities, weak peripheral pulses, and hepatomegaly, and they were admitted in a pre-shock state (4). Many children had tachycardia at presentation, which was usually sinus in form without any other significant signs on an electrocardiographic (EKG). The tachycardia had different causes and was a result of various, simultaneous etiologies (fever, dyspnea, pain, or anxiety) (5). In late April 2020, a report was published in the United Kingdom announcing the description of a new hyperinflammatory disease that was associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Following that report, other countries have published cases with similar signs, and finally, this phenomenon has been described as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) or pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS) (6). The cardiac associations of MIS-C are myocardial dysfunction, coronary artery disease, arrhythmias [including S-T segment alterations, QT correction (QTc) prolongation], and atrial and ventricular premature contractions (7).

The underlying mechanism of myocardial dysfunction in MIS-C has not yet been completely understood. The acute myocardial damage may be related to acute infection; nevertheless, the myocardial inflammation and dysfunction can be explained by a second phase of post-viral immunological reaction and systemic hyperinflammation, leading to a combination of cardiogenic and distributive shock (8). In 6 - 24% of patients, coronary artery dilation or aneurysms have been described (9). Mild coronary artery dilation with Z-scores of 2 - 2.5 has been reported in most cases. As coronary artery Z-scores are based on the measurement of coronary arteries in healthy, nonfebrile children, some of the findings in the acute phase may be related to vasodilation of coronary arteries due to fever and inflammation. Large and giant coronary artery aneurysms (10) have also been reported, and the progression of coronary aneurysm after hospital discharge has raised concerns for intimal disruption of coronary arteries (11). Many studies have reported the late development of coronary artery aneurysm; therefore, it is mandatory to follow up with those patients in terms of late cardiac complications. Studies have been focusing on arrhythmic manifestations of the disease and have revealed rhythm abnormalities of variable severity in 7 - 60% of patients. The most frequently reported electrocardiogram (ECG) anomalies were non-specific and included ST segment changes, prolonged QTc, and premature atrial or ventricular rhythm (12). In one report, first- and second-degree atrioventricular blocks were demonstrated, whereas atrial fibrillation was described in two reports. Sustained arrhythmias that have led to hemodynamic collapse and the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support have also been reported (13, 14). Cases of drug-related myocardial injury have been reported due to various pharmacologic agents, mainly antivirals (remdesivir, lopinavir/ritonavir, favilavir), antimalarials [chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)], corticosteroids, monoclonal antibodies, and antibiotics (azithromycin). A few antiviral drugs may lead to heart failure, arrhythmia, or other cardiovascular disorders. Antimalarials and some antibiotics can prolong the QT interval and progress to malignant arrhythmias (15).

In a report from the United States, only 4% of the pediatric group with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU have died, more than 80% of whom suffered from comorbid complications (16). Severe infection has been reported in infants and those with underlying comorbidities such as hematologic-oncologic malignancies, neurologic disorders, cardiovascular disease, end-stage renal disease, diabetes, and metabolic or immune deficiencies, requiring ICU admission (17, 18). Patients suffering from pulmonary hypertension and those under immunosuppressive therapy must be under special consideration (19). There are few reports about the cardiac involvement of children following COVID-19 disease, and the data about cardiac complications of MIS-C are sparse. In this study, we report the cardiac complications of pediatric patients suffering from COVID-19 disease to draw attention not to ignore the cardiac involvement of patients, even though the clinical presentation may not reveal any specific signs of cardiac disease.

2. Objectives

This study was aimed at evaluating the clinical, laboratory, imaging, and cardiac characteristics of children diagnosed with COVID-19 infection in Tehran during the first year of the pandemic.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2020 to March 2021, including all patients (n = 47) hospitalized at Aliasghar Children’s Hospital, Tehran, diagnosed with COVID-19 either by computed tomography (CT) scan or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Patients suffering from any previous congenital heart disease or acquired heart disease diagnosed before COVID-19 were excluded.

According to their method of diagnosis, the patients were divided into three groups: (1) Diagnosed by PCR; (2) with a negative PCR test but with a chest CT scan confirming COVID-19; (3) with a positive PCR and chest CT finding. Data were obtained from hospital medical records and included demographic information, presenting symptoms at the time of admission, hospitalization information (including hospital stay duration and the outcome of care), laboratory data, and echocardiographic evaluation. A standard 12-lead EKG with QTc was assessed for the presence of arrhythmias. Echocardiography was performed for all of the patients, considering myocardial function, valvular impairment, and coronary artery evaluation, which was performed by calculating the Z-score for evaluating the presence of dilatation or abnormal echogenicity and aneurysm formation.

3.2. Data Analysis

Quantitative variables are reported as mean ± SD, and qualitative variables are described by percentage. Analysis is performed using the ANOVA test for quantitative variables, whereas qualitative variables are compared using the χ2 (chi-square) test. A P-value of < 0.05 was chosen as the cutoff for significance.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences under the code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1399.648.

4. Results

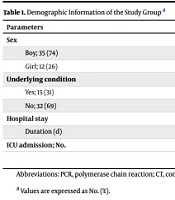

A total of 47 patients were admitted with a diagnosis of COVID-19 during one year at Aliasghar Children’s Hospital, including 35 boys and 12 girls with a mean age of 2.73 ± 0.94 years (ranging from one month to 14 years), (SD = 2.1).Eighteen were diagnosed by PCR only, 17 by CT findings, and 12 were positive for both. The patient sex showed no significant difference across the study groups (Table 1).

| Parameters | PCR; 18 (38) | CT; 17 (36) | PCR+CT; 12 (26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Boy; 35 (74) | 13 (72) | 12 (70.6) | 10 (83.3) |

| Girl; 12 (26) | 5 (27.8) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (16.7) |

| Underlying condition | |||

| Yes; 15 (31) | 6 (33.3) | 3 (17.7) | 6 (50) |

| No; 32 (69) | 12 (66.7) | 14 (82.4) | 6 (50) |

| Hospital stay | |||

| Duration (d) | 7.17 | 10.12 | 11.92 |

| ICU admission | 3 (16.7) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (25) |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CT, computed tomography; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

The highest rates of hospitalization were in October (18 patients) and November (12 patients), respectively. Most of our patients needed no more than 15 days of hospitalization (9.4 ± 1.09 days) (SD = 5.43), and 10 required intensive care (mean duration of ICU stay = 6.8 ± 5.2 days) (SD = 3.66). In terms of the duration of hospitalization, the study groups were not significantly different (P > 0.11) and ICU admission (P = 0.87, Table 1). Fifteen (31.9%) of the patients had an underlying condition, the most prevalent of which was acute lymphoblastic leukemia (4 patients). The study groups were not different regarding the presence of an underlying condition (P = 0.18). Four (8.4%) of the patients initially presented with atypical symptoms that would lead to other diagnoses: Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), seizure, hematuria, and status epilepticus. Fever, cough, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, and myalgia were the most common initial presenting symptoms. Their prevalence among the study groups was not significantly different (P > 0.67). Table 2 shows the laboratory results among the three study groups.

| Variables | PCR | CT | PCR+CT | ANOVA Test (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR (mm/h); 0 - 15 | 22.29 ± 23.82 | 31.27 ± 38.89 | 32.56 ± 23.19 | 0.656 |

| CRP (mg/dL); 0.3 - 1 | 22.1 ± 20.92 | 33.31 ± 42.57 | 20.8 ± 33.25 | 0.454 |

| D-dimer (µg/dL); 0.22 - 0.46 | 1.83 ± 1.03 | 1.37 ± 0.73 | 1.38 ± 0.85 | 0.482 |

| AST (U/L); 10 - 40 | 50.23 ± 22.53 | 34.2 ± 12.31 | 62.36 ± 74.09 | 0.367 |

| ALT (U/L); 6 - 50 | 34.54 ± 21.48 | 25.2 ± 17.03 | 38.91 ± 16.88 | 0.252 |

| CPK (U/L); 5 - 45 | 116.08 ± 84.46 | 110.7 ± 83.91 | 49.43 ± 35.73 | 0.167 |

| LDH (U/L); 60 - 170 | 642.31 ± 223.4 | 622.2 ± 199.84 | 538.88 ± 379.95 | 0.678 |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CT, computed tomography.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

A comparison between the study groups in terms of the most commonly prescribed medications [azithromycin, HCQ, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)] showed no significant difference (P > 0.16). Table 3 shows the most commonly prescribed drugs among the three groups.

| Drugs | PCR | CT | PCR+CT | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azithromycin | 5 ± 0.47 | 5.62 ± 2.53 | 5.38 ± 1.06 | 0.711 |

| HCQ | 7.14 ± 2.41 | 10 ± 4.17 | 10.8 ± 3.27 | 0.168 |

| IVIG | 3.67 ± 3.79 | 3.57 ± 2.15 | 4.75 ± 4.11 | 0.826 |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CT, computed tomography; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Electrocardiography was performed for all the patients, among which 3 (9.4%) had abnormalities: S-T elevation in one patient and long Q-T in two patients, all of which resolved later in the course of hospitalization. Abnormal coronary artery was observed in 5 patients during echocardiography. Two patients had a left anterior descending Z-score between 2 and 2.5, and three had a Z-score above 2.5. After treatment with IVIG and anticoagulants, at the time of discharge, echocardiography showed that all the coronary arteries had returned to normal size. These patients were categorized as having MIS-C. The two most common valvular disorders seen in the patients were tricuspid and mitral regurgitation, the latter of which was significantly more common among the PCR+CT group (P = 0.03). Other echocardiographic measures did not differ significantly across the study groups (P > 0.16, Table 4). The dilatation of the coronary arteries was resolved at the follow-up echocardiography. The dilatation of the coronary arteries and tricuspid and mitral valve regurgitation returned to normal at follow-up echocardiography.

| Valvular Disorders | PCR | CT | PCR+CT | Chi-Square (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 7 (63.7) | 8 (66.7) | 7 (87.5) | 0.483 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 1 (9.1) | 3 (25) | 5 (62.5) | 0.037 |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CT, computed tomography.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

Coinciding with the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic throughout Iran, between the months of October and November 2020, most of the patients were admitted in autumn. The mean age of the patients was 2.73 years, and the majority of them were boys (74.5%). Shekerdemian et al. reported that of the 48 children with COVID-19 who were admitted to PICUs, 25 (52%) were male, and the median (range) age was 13 (4.2 - 16.6) years. The median (range) of stay at PICU and hospital admission for those who had been discharged were 5 (3 - 9) days and 7 (4 - 13) days, respectively (2). The median age of the patients in the study by Dong et al. (18) was 7 years, but they did not study the hospitalized COVID-19 patients. They also reported more boys (57.4%) diagnosed with COVID-19 than girls, which is similar to the study by Belhadjer et al. (20). The mean duration of hospitalization in our study groups was 9.4 days, and 63.8% of our patients needed less than 10 days of hospitalization. Ten (21%) of our patients needed ICU admission.

Three of our patients were under mechanical ventilation. One of them was a 5-day-old neonate who was admitted with tachypnea and cyanosis. Two other patients were admitted with seizures. One of them expired after two days, and the other was a 28-month-old child who was under mechanical ventilation for 10 days and was discharged after a 23-day hospital stay in good condition. Dong et al. (18) in 2020 reported 2135 children suspected of COVID-19, of whom 728 (34.1%) were PCR positive. Only 21 (2.9%) had severe and critical conditions. In 0.6% of their patients, symptomatic myocardial damage and heart failure were observed. Sun et al. (21) reported 8 children with PCR-positive COVID-19 who were admitted to the ICU in Wuhan, China. Three of them were critically ill and required mechanical ventilation or were in shock. Five patients were severely affected and had tachypnea and decreased oxygen saturation. Hospital stay time was between 10 and 26 days, and the critically ill patients were hospitalized for more than 20 days, which is similar to our report. The age range of their patients varied between 2 months and 15 years (20). Other studies have reported 10 and 15 days of hospitalization, although with higher rates of ICU admission (> 51%) (21, 22).

We also had two MIS-C cases, but no depressed ventricular function or cardiac enzyme elevation was observed. Samuel et al. reported troponin elevation in 9 (28%) patients (22), but in our study, pro-BNP and troponin levels were within the normal range. Li reported that complete blood counts were the most common laboratory results described by different authors. Overall, leukocytes were within normal values (7.1 × 103/μL), whereas neutrophils were mildly decreased (44.4%) while lymphocytes were marginally elevated (39.9%). Liver and renal function tests were normal. D-dimer, procalcitonin, creatine kinase, and interleukin-6 were four inflammatory markers that were above the mean (11). In the study by Samuel et al. in New York, 2/3 of the admitted patients had underlying disorders, one-fourth of which were hematologic-oncologic disorders (22). In our study, 15 patients (31.9%) had an underlying disorder, and consistent with Samuel’s study, the most common disorder was acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The most common clinical manifestations of our patients were fever and tachypnea, both of which were resolved on discharge (P < 0.001). The most common presenting symptoms in Samuel’s study were fever (67%), cough (36%), gastrointestinal disorders (31%), and dyspnea (24%), which were in accordance with our study.

In the study by Belhadjer et al., fever and fatigue were observed in all of the patients. Gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms were observed in 83% and 65% of the patients, respectively (20, 22). In the patients of our study, abnormal EKG was observed in 3 patients (9.4%); two of them had prolonged QTc that resolved during the course of hospitalization. First-degree heart block was observed in one patient who was admitted to the ICU, which was not repeated after treatment with HCQ was stopped. Samuel et al. (22) reported 10 abnormal EKGs in 28 patients. There were low voltage QRS complexes (18%), left ventricular hypertrophy in 4%, right ventricular hypertrophy in 4%, left axis deviation in 4%, and ST-T changes in 4%. Arrhythmias were observed in 6 patients (17%). The patients were hemodynamically stable, and the arrhythmias resolved spontaneously. Two of the patients had a diagnosis of myocarditis. There was a significant correlation between arrhythmia and increased levels of troponin (P = 0.03). Likewise, only one patient was found to have an arrhythmia in Belhadjer’s report (20), even though their patients were mostly hospitalized with cardiogenic shock.

Due to myocarditis, patients might experience dysrhythmias such as supraventricular tachycardia, premature atrial and ventricular complexes, and atrioventricular blocks. Recently, the Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology, in collaboration with the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and the American Heart Association, published an article explaining that in the acute phase of severe COVID-19, arrhythmias are not unexpected due to hypoxia and electrolyte disturbances (23). Yet, it remains a question why arrhythmias occur less severely in children than in adults (24). In a study conducted by Farshidgohar and Mahram, cardiac involvement was reported in 24% of pediatric patients with the diagnosis of MIS-C (25). Ventricular dysfunction, coronary artery dilatation, mitral regurgitation, and pericardial effusion have been observed. Coronary artery aneurysm was reported in 1% of their cases (Z-score 2.5 - 5), and 3% of the patients showed coronary artery ectasia (Z-score < 2.5). The aneurysm was not resolved in the one-year follow-up. In a report by Ng MY et al., the use of cardiac imaging is recommended in the management of patients with COVID-19. Eighty-eight percent of their patients had EKG changes, 44% had raised troponin levels, and after discharge, 69% were asymptomatic. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) has revealed the noninvasive detection of myocardial inflammation. Nineteen percent of their patients had nonischemic late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) with elevated global T2-mapping values (57 - 62 ms), fulfilling the Lake Louise criteria for myocardial inflammation (26).

It is noteworthy that some of the cardiac complications might be due to the medications prescribed to COVID-19 patients themselves. The most commonly used drugs include azithromycin, HCQ, antivirals, and corticosteroids. Azithromycin can cause dysrhythmias, prolonged QTc, and torsade de pointes. The HCQ and antivirals are myocardiotoxic drugs that might worsen cardiomyopathy, bundle branch blocks, atrioventricular blocks, ventricular arrhythmias, torsade de pointes, and QTc prolongation. Corticosteroid use leads to fluid retention, electrolyte disturbance, and hypertension (22). Coronary artery dilatation was observed in five of our patients, which resolved at the echocardiography performed before discharge. In the study by Belhadjer et al., the patients had no prior cardiac condition and were diagnosed either by PCR or CT scan. Six patients (17%) had dilated coronary arteries (Z-score > 2), 25 (71%) had an ejection fraction lower than 50%, they all had high D-dimer, CRP, troponin I, and Pro-BNP levels, and 80% presented with cardiogenic shock (20). Riphagen et al. reported 8 children presenting with hyperinflammatory shock. They found a giant coronary aneurysm in one, and refractory shock with arrhythmia in another patient (3). Verdoni et al. reported cardiac involvement in 20% of their patients. Echocardiography depicted a left coronary aneurysm (> 4 mm), reduced ejection fraction, and mitral regurgitation in the patients (4).

Similarly, in the study by Ramcharan et al. (14), 9 out of 15 patients had EKG abnormalities and 7 had arterial involvements. Conversely, in a 2020 Chinese study on 2135 children with COVID-19, only 0.6% had symptomatic myocardial damage and/or heart failure (18). Apparently, the higher rate of cardiac and coronary involvement in early European studies is related to the hyperinflammatory state caused by COVID-19, which also causes the elevation of immunoglobulin levels. The most commonly prescribed medications in Samuel’s report (22) were HCQ (69%) and azithromycin (25%), which is similar to our prescriptions. Another study comparing MIS-C, Kawasaki disease, and healthy children (17) used corticosteroids (96%), aspirin (86%), IVIG (80%), vasopressors (78%), and anticoagulants (73%) most commonly. Twenty percent of their MIS-C patients needed invasive mechanical ventilation, and one had right coronary artery (RCA) involvement. In 61% of their cases, troponin I and Pro-BNP were elevated and had a lower LVEF than the other two groups. A study on 48 COVID-19 children in an American PICU reports that only 12 patients needed inotrope medications, and thus, cardiac involvement in children with COVID-19 is not very common (2). However, cardiac biomarkers and echocardiographic studies are not reviewed in their report, and whether or not the need for inotropes has been due to primary cardiac dysfunction is questionable.

5.1. Conclusions

One of the most serious complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection is cardiovascular involvement. There are few reports of pediatric critically ill patients; however, various clinical presentations have been reported in children. Therefore, it is mandatory to investigate myocardial injury and cardiovascular involvement to avoid misdiagnosing severe clinical problems. There are limited data on pediatric patients, including children suffering from grave underlying diseases; however, some reports have shown that these patients are at increased risk of complications, and the mortality rate is higher among this group. Knowledge about the clinical presentations of the disease and the various courses of each patient would lead to a better understanding of the illness and improvements in treatment measures for better outcomes for the patients.