1. Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which first appeared in China in December 2019, rapidly spread worldwide as a disaster (1). Despite the perception that the pandemic is over, research into its effects continues due to its profound impact on health and economic systems. Studies advocate for meticulous planning to provide comprehensive strategies for unforeseen circumstances in the future (2, 3). The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has also impacted the procedural approaches of physicians and especially anesthesiologists (4). Some specialties, such as anesthesiologists who have been directly involved in the management of these patients, are at higher risk for exposure to aerosols and droplet contamination (5, 6). The high mortality rate among healthcare workers during the early stages of the pandemic underscores the need for comprehensive training and adherence to safety protocols. Therefore, the preparedness of frontline physicians must be the top priority of all healthcare policymakers (7-9). Thus, it is necessary to assess the knowledge and practices to improve occupational safety for physicians and identify existing gaps to decide on better plans. So, developing further research can greatly help policymakers to provide better programs (10, 11). Studies have illustrated different results regarding this topic due to several influential factors (12-15). In this manner, according to these discrepancies, findings of similar studies from different regions could not be generalized and each province should pay attention to its own problems.

2. Objectives

Our study aimed to evaluate the knowledge and practices of anesthesiologists in Guilan province regarding the management of COVID-19 patients, with the goal of identifying gaps and enhancing preparedness for future health emergencies. Definitely, it cannot be the last mortal global infectious crisis.

3. Methods

Type of study and population studied: After the study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS), and receiving the ethics code of ID IR.GUMS.REC.1401.463, this cross-sectional analytical study was conducted in academic and private centers of Guilan-Iran during 2023.

Sample size calculation method: In this study, the census method was used for the process of collecting data.

The data collection tool: It was a researcher-made questionnaire that was prepared by experienced professors in the intensive care unit, as well as reliable references and adherence to COVID-19 management guidelines. The first part included demographic information, and the second part included questions to assess physicians' knowledge. In order to evaluate the validity of the questionnaire, ten expert faculty members of the Anesthesia Department reviewed the questions, and the content validity ratios for all the items were higher than 0.62. The reliability of the questionnaire was also confirmed, with the Cronbach alpha determined to be 0.731. The panel members described the questionnaire items as relevant and without the need for serious re-evaluation. The scoring system for the twenty questions was as follows: One point was considered for each correct answer and zero for wrong answers. So, the minimum score was zero and the maximum score was 20. The study focused on their knowledge regarding anesthesia techniques, disease manifestations, anticoagulation management, resuscitation practices, intubation methods, and maternal-newborn separation protocols.

The mentioned questionnaire was filled out via a direct interview by a trained medical student.

Statistical analysis: The collected data were entered into SPSS software version 22. Descriptive statistics of mean, standard deviation, and frequency were used to describe the data. t-test was applied to analyze continuous quantitative variables under normal distribution status, and chi-square test was used to analyze qualitative variables. The significance level was considered P < 0.05. Mann-Whitney U and Kruskall-Wallis tests were used to analyze under non-normal distribution status.

4. Results

In this survey, sixty-one specialists; 15 (21.4%) faculty members and 46 (65.7%) from the private sector, and 9 (12.9%) anesthesia residents participated.

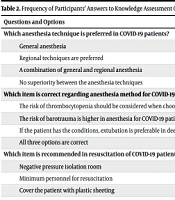

The characteristics of participants such as gender, years of experience, academic degree, and having the certificate of educational courses are shown in Table 1. The frequency of individuals’ answers to 20 questions is presented in Table 2. The results illustrated that there was a statistically significant difference between the obtained scores and years of experience (P = 0.022), academic degree (P < 0.001), and completion of educational courses of COVID-19 (P = 0.02), however not about physicians' gender (P = 0.372) Table 3. Using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test, it was determined that the distribution of data related to the sum of scores obtained from the questionnaire measuring awareness of the management of patients with COVID-19 by the specialists and anesthesia residents in the study did not have a normal distribution (KS = 0.161 and P < 0.001).

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 50 (71.4) |

| Female | 20 (28.6) |

| Years of experience | |

| < 10 | 20 (28.6) |

| 10 - 20 | 30 (42.9) |

| 21 - 30 | 20 (28.6) |

| Mean ± SD (min-max) | 15.75 ± 8.09 (2 - 30) |

| Academic degree | |

| Faculty members | 15 (21.4) |

| Private sector | 46 (65.7) |

| Residents | 9 (12.9) |

| Participating in educational courses | |

| Yes | 57 (81.4) |

| No | 13 (18.6) |

| Field of practice | |

| Operating room | 52 (74.3) |

| ICU | 18 (25.7) |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are as expressed as No (%) unless otherwise indicated.

| Questions and Options | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Which anesthesia technique is preferred in COVID-19 patients? | |

| General anesthesia | 5 (7.1) |

| Regional techniques are preferred | 56 (80) |

| A combination of general and regional anesthesia | 6 (8.6) |

| No superiority between the anesthesia techniques | 3 (4.3) |

| Which item is correct regarding anesthesia method for COVID-19 patients? | |

| The risk of thrombocytopenia should be considered when choosing a regional method | 3 (4.3) |

| The risk of barotrauma is higher in anesthesia for COVID-19 patients | 15 (21.4) |

| If the patient has the conditions, extubation is preferable in deep conditions | 0 (0) |

| All three options are correct | 52 (74.3) |

| Which item is recommended in resuscitation of COVID-19 patients? | |

| Negative pressure isolation room | 1 (1.4) |

| Minimum personnel for resuscitation | 1 (1.4) |

| Cover the patient with plastic sheeting | 0 (0) |

| All three are correct | 68 (97.1) |

| Which item is correct in airway managing of a COVID-19 patients? | |

| Intubation with fiberoptic | 15 (21.4) |

| Intubation with video laryngoscope | 46 (65.7) |

| Large laryngeal mask | 7 (10) |

| I-Gel with the smallest possible size | 2 (2.9) |

| Which item is wrong in COVID-19 patients’ resuscitation (BLS)? | |

| Cover the nose and mouth with a thin towel | 17 (24.3) |

| Perform CPR by the person who has had the closest contact with the patient | 1 (1.4) |

| Perform one breath after every 30 chest compressions | 48 (68.6) |

| Quickly transfer the patient to the hospital with at least 2 companions | 4 (5.7) |

| Which of the following is correct regarding decision-making regarding resuscitation of COVID-19 patients? | |

| All COVID-19 patients should undergo resuscitation | 33 (47.1) |

| A patient with a definitive diagnosis of COVID-19 should not undergo resuscitation | 0 (0) |

| A decision should be made based on the patient's chance of survival and the risk of transmitting the infection | 0 (0) |

| The patient's legal guardian will make this decision | 37 (52.9) |

| If supraglottic are used for ventilation during resuscitation for a COVID-19 patient, which should be the ventilation method? | |

| 2 breaths every 30 compressions | 39 (55.7) |

| 1 breath every 6 seconds | 26 (37.1) |

| 4 breaths every 30 compressions | 4 (5.7) |

| 2 breaths every 30 seconds | 1 (1.4) |

| Which option is correct regarding the initiation of anticoagulants in the resuscitation of a COVID-19 patient? | |

| Start as soon as possible | 33 (47.1) |

| Start if resuscitation is successful | 10 (14.3) |

| Anticoagulants should not be given during resuscitation | 24 (34.3) |

| This intervention is absolutely contraindicated | 3 (4.3) |

| Which of the following is correct in resuscitation of COVID-19 patients during intubation? | |

| Stopping CPR when attempting intubation | 46 (65.7) |

| Continuing CPR | 19 (27.1) |

| Stopping CPR if the first attempt is unsuccessful | 3 (4.3) |

| Reducing the rate and depth of compressions during intubation | 2 (2.9) |

| What is the correct way to intubate COVID-19 patients? | |

| Cuffed intubation with rapid sequence induction | 48 (68.6) |

| Use of supraglottic airway devices | 4 (5.7) |

| Intubation followed by at least 3 minutes of mask ventilation | 4 (5.7) |

| Awake intubation with local anesthesia | 14 (20) |

| Which item is correct about video laryngoscopy in COVID-19 patients? | |

| Reduces intubation failures. | 37 (52.9) |

| Not recommended in patients with COVID-19. | 4 (5.77) |

| Does not reduce transmission of infection. | 5 (7.1) |

| It is the first choice in COVID-19 patients. | 24 (34.3) |

| Which muscle relaxant do you recommend for intubation of a COVID-19 patient? | |

| Cisatracurium | 13 (18.6) |

| Atracurium | 17 (24.3) |

| Pancuronium | 0 (0) |

| Rocuronium | 40 (57.1) |

| Which of the following is correct in determining the appropriate time for intubation of COVID-19 patients? | |

| Response rate to non-invasive methods | 0 (0) |

| Pathological and pathophysiological status of the patient | 1 (1.4) |

| Acute course of the disease | 1 (1.4) |

| All three are correct | 68 (97.1) |

| Which of the following in managing the airway of COVID-19 patients increases the spread of respiratory droplets? | |

| Stylet | 1 (1.4) |

| Bougie | 8 (11.4) |

| Ventilation with a mask | 58 (82.9) |

| Video laryngoscope | 3 (4.3) |

| Which of the following can be the manifestations of COVID-19 disease? | |

| Asymptomatic | 1 (1.4) |

| Common cold | 0 (0) |

| Acute symptoms and respiratory failure | 11 (15.7) |

| All of them | 58 (82.9) |

| What is the appropriate position for a COVID-19 patient when extubating? | |

| Prone | 1 (1.4) |

| Left Lateral | 6 (8.6) |

| Head down | 2 (2.9) |

| 45 degrees Ramp-head up | 61 (87.1) |

| What is the recommended positioning for COVID-19 patients during hospitalization? | |

| Prone | 58 (82.9) |

| Supine | 9 (12.9) |

| Left lateral | 3 (4.3) |

| Right lateral | 0 (0) |

| What is the main cause of cardiorespiratory arrest in COVID-19 patients? | |

| Arrhythmias | 2 (2.9) |

| Myocardial ischemia | 6 (8.6) |

| Drugs | 1 (1.4) |

| Hypoxemia | 61 (87.1) |

| What type of arrhythmia is common in cardiorespiratory arrest in COVID-19 patients? | |

| VF | 14 (20) |

| Asystole | 20 (28.6) |

| VT | 19 (27.1) |

| Occurs in equal proportions | 17 (24.3) |

| Which item is correct about a newborn from an infected mother? | |

| The newborn is definitely infected | 1 (1.4) |

| There is a risk of COVID-19 transmission from mother to baby | 49 (70) |

| The baby has sufficient immunity in the first months | 4 (5.7) |

| The baby must be completely separated from the mother | 16 (22.9) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019.

| Variables and Status | Median | Min-Max | P-Value |

| Gender | 0.372 | ||

| Male | 14 | 8 - 20 | |

| Female | 13 | 8 - 20 | |

| Years of experience (y) | 0.022 | ||

| < 10 | 12.5 | 8 - 20 | |

| 10 - 20 | 13 | 8 - 20 | |

| 21 - 30 | 14.5 | 9 - 19 | |

| Academic degree | < 0.001 | ||

| Faculty members | 15 | 13 - 20 | |

| Private sector | 14 | 8 - 16 | |

| Resident | 11 | 8 - 15 | |

| Participating in educational courses | 0.02 | ||

| Yes | 14 | 8 - 20 | |

| No | 12 | 8 - 15 | |

| Field of practice | 0.423 | ||

| Operating room | 14 | 8 - 20 | |

| ICU | 14.5 | 8 - 17 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

5. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unprecedented challenges to healthcare systems globally, and anesthesiologists as key players in managing critically ill patients face unique risks and have important responsibilities in this way. Our study aimed to evaluate the knowledge and practices of anesthesiologists in Guilan province regarding the management of COVID-19 patients, with the goal of identifying gaps and enhancing preparedness for future health emergencies. The findings of our study presented that anesthesiologists possess a reasonable level of knowledge about COVID-19 management protocols, but there are significant areas for enhancement. This aligns with previous research that has highlighted variability in knowledge and practices among healthcare professionals during the pandemic (12-15).

Factors such as access to updated information, training opportunities, and institutional support, the quality and quantity of training courses, supervisory and monitoring systems are all among the influential factors and play crucial roles in shaping the preparedness of anesthesiologists. Furthermore, assessment methods, question difficulty, and questionnaire standardization influence outcomes, and the mode of questionnaire distribution — whether face-to-face or via email — can affect response quality. Policymakers must prioritize these educational strategies to ensure that frontline healthcare workers are adequately prepared for emerging health threats.

A noteworthy finding from our study is the variability in practices among anesthesiologists based on demographic factors such as years of experience and type of practice setting. It was determined that more years of experience were positively associated with higher scores. So that, work experience above 20 achieved the highest scores. This highlights the importance of tailored training programs that consider the specific needs and contexts of different groups within the anesthesiology community. Collaborative efforts between academic institutions and clinical practices can facilitate knowledge sharing and promote best practices (16-18).

Regarding the question of the anesthesia technique, 80% of respondents recognized regional anesthesia as preferable for COVID-19 patients, aligning with literature that indicated better outcomes and lower infection transmission risks associated with regional methods (19-21). Regarding the item of disease manifestations, 82% understood that COVID-19 presents a spectrum from asymptomatic to severe respiratory failure. However, this level of awareness is not acceptable and is concerning given the potential for fatal consequences stemming from misinformation (22). Less than half of participants correctly identified when to initiate anticoagulants, with 34.3% erroneously believing they should be avoided. This indicates a significant gap in understanding the thromboembolic risks associated with COVID-19 (23).

Participants acknowledged that supraglottic airway ventilation poses a higher risk of viral spread compared to intubation. Within 52.9% believed the most exposed healthcare workers should perform basic resuscitation and highlight a potential risk of infection control practices. The majority (65.7%) preferred the glide scope for intubation to minimize exposure during procedures (24). Seventy percent (70%) did not recommend separating newborns from infected mothers, while 22.9% supported complete separation and prohibiting breastfeeding. Literature suggests that separation does not prevent transmission and can adversely affect newborn health (17).

Participants who engaged in educational courses demonstrated higher knowledge scores, underscoring the need for ongoing training programs to enhance occupational safety skills among medical staff (18). The findings reveal critical areas where knowledge gaps exist among anesthetists regarding COVID-19 management. The low awareness of anticoagulation protocols and the misconceptions surrounding maternal-newborn separation are particularly concerning given their potential implications for patient care.

The discrepancy between the percentage of participants who attended COVID-19 training courses and their correct responses raises important questions. It suggests that attendance at these workshops may not necessarily translate into practical knowledge application in clinical settings. This could be due to several factors. Participants may attend training primarily to obtain certificates rather than to genuinely enhance their clinical skills and knowledge. This highlights a potential lack of intrinsic motivation to apply learned concepts in practice. The content delivered in these training courses may not be adequately aligned with the real-world challenges faced by anesthesiologists throughout the pandemic. A review of course materials and objectives may be necessary to ensure relevance and applicability. The practical components of training may not be standardized, leading to variability in skill acquisition among participants. Ensuring consistent practical experiences in all training sessions could enhance learning outcomes. The manner in which participants are assessed during these courses may not effectively evaluate their understanding or readiness to apply knowledge in clinical settings. More robust assessment strategies could help identify areas needing further focus. There is a clear necessity for regular evaluations of physicians' performance in clinical practice post-training, as well as mechanisms to reinforce learning and address any ongoing knowledge deficiencies.

5.1. Limitations

Despite the valuable information obtained, we acknowledge some limitations. First, almost 25% of the anesthesiologists refused to fill the questionnaire. Second, the number of anesthesia residents was very limited. It should be noted that at the outbreak of COVID-19 and the frequent mortality reports, great concern arose among the assistantship volunteers. Given the nature of the field of anesthesia, anesthesiologists are more involved with COVID-19, which leads to a significant drop in the entry of anesthesia assistants. Third, the study group was limited to the anesthesiologists, but other specialists are also at risk, which will be considered for future studies.

5.2. Conclusions

It was determined that while our study provides valuable insights into the knowledge and practices of anesthesiologists in Guilan province regarding COVID-19 management, it also emphasizes the need for continuous evaluation and improvement in this area. As we move forward, it is crucial to leverage the lessons learned from the pandemic to enhance the resilience of healthcare systems and prepare for future public health crises. According to these findings, there is a need for the participation and organized intervention of the country’s health policymakers, implementation of consistent regular training sessions focused on COVID-19 management protocols, and encouragement of collaborative research to share insights across healthcare centers.