1. Background

Psychiatric patients face an elevated risk of certain infections, not only due to lifestyle factors but also possibly because of shared underlying etiological mechanisms. The association between infectious diseases and psychiatric disorders is well documented in epidemiological studies, which report a high rate of comorbidity between these conditions (1). Certain infections have been implicated in the development of major psychiatric disorders (2).

Although numerous reports have highlighted parasitic infections among individuals with mental illnesses, there is a global scarcity of research specifically examining the link between mental disorders and parasitic diseases. The public health importance of addressing these infections in this population stems from the complex relationship between mental and physical health. Parasitic infections can significantly deteriorate the overall health of mentally ill patients, potentially worsening their psychiatric symptoms and complicating treatment outcomes. Additionally, factors commonly associated with mental illness — such as poor hygiene, reduced access to medical care, and weakened immune function — increase vulnerability to parasitic infections (3).

Toxoplasma gondii is a widespread intracellular protozoan parasite infecting nearly one-third of the global population, affecting individuals in both low-income and high-income countries (4). Estimates suggest that it affects approximately 30% of the world population, particularly in tropical countries where environmental conditions support parasite survival (5).

Felids serve as the exclusive definitive hosts for T. gondii, releasing large quantities of oocysts — often in the millions — through their feces. Once in the environment, these oocysts sporulate and develop into their infectious form (6). Infection can occur through the ingestion of sporulated oocysts that have contaminated food crops, soil, or drinking water (7, 8). The ingestion of bradyzoites through raw or undercooked meat represents one of the two main horizontal transmission routes. These infectious stages significantly contribute to the burden of postnatal toxoplasmosis and have been associated with sporadic outbreaks of acute symptomatic disease in individuals with normal immune function (9).

Although infections are usually asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, T. gondii has been implicated in various neuropsychiatric disorders since it can cause latent infections in brain tissue. Previous reports have clearly demonstrated a strong association between T. gondii infection and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression (10-14).

These findings emphasize the potential link between T. gondii infection and psychiatric disorders; certain behaviors and environmental exposures may increase the risk of infection in patients with psychiatric diseases. However, data on toxoplasmosis seroprevalence and corresponding risk factors among psychiatric patients in Iran, particularly in Qazvin province, are scarce (15).

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection and associated risk factors in psychiatric patients of Qazvin province. An understanding of these associations is crucial for developing targeted interventions to reduce the risk of toxoplasmosis in this vulnerable population.

3. Methods

3.1. Ethical Considerations

Prior to initiating the study, authorization and approval were obtained from the management of 22 Bahman Psychiatric Hospital. Additionally, the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, Iran (IR.QUMS.REC.1403.233). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

3.2. Study Area

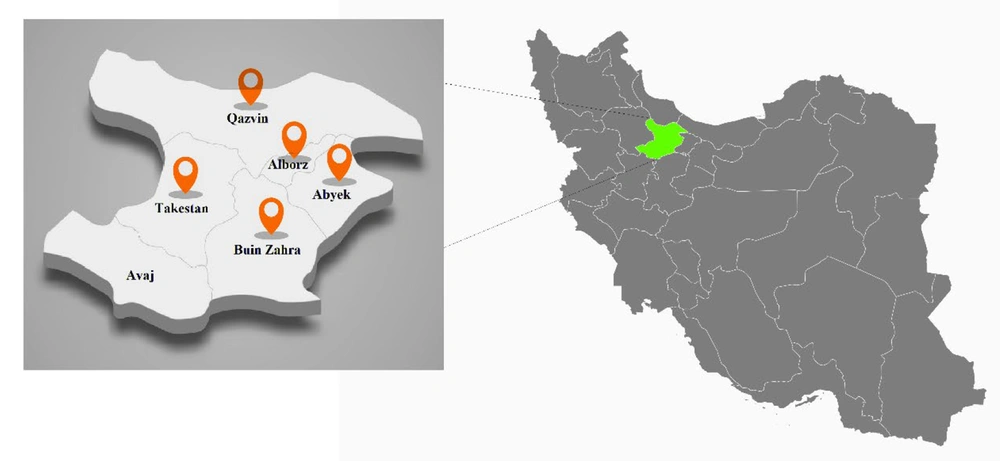

The cross-sectional study was conducted from December 2023 to November 2024 in Qazvin province. The province encompasses an area of 15,821 square kilometers, positioned between longitudes 48°45' and 50°50' east of the Greenwich Meridian and latitudes 35°37' and 36°45' north of the equator. Situated in the northwest region of Iran’s central plateau, the province is administratively divided into six counties: Abyek, Avaj, Alborz, Buinzahra, Takestan, and Qazvin (16, 17) (Figure 1).

The province is bordered by Mazandaran and Guilan to the north, Hamedan and Zanjan to the west, Markazi to the south, and Tehran province to the east (17). The region experiences an average annual rainfall of approximately 280 mm, with precipitation levels decreasing progressively from the northern to the southern areas. The mean annual temperature is 15.5°C, while the potential evapotranspiration averages around 2,200 mm (18).

3.3. Study Population

The samples were selected from patients referred to 22 Bahman Psychiatric Hospital in Qazvin province, Iran. Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire containing demographic information (sex, profession, residential region, and type of residence), information related to underlying disease, history of substance abuse, type of psychiatric disorder, and information related to possible transmission routes of T. gondii infection (contact with animals, and raw meat/egg consumption).

3.4. Sampling Method

All psychiatric patients referred to 22 Bahman Psychiatric Hospital during the study period who met the inclusion criteria (diagnosed psychiatric disorder, willingness to participate, and ability to provide informed consent) were invited to participate. A consecutive sampling method was applied until the required sample size (n = 179) was reached.

3.5. Sample Collection and Serological Assay

Approximately 5 mL of blood was collected from each patient. The samples were centrifuged at 1,000 rpm to separate the serum, which was then stored at -20°C until further analysis. The sera from all participants were tested for anti-T. gondii immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Pishtaz Teb Diagnostics, Iran).

The IgG antibody titers were quantified by measuring the absorbance at an optical density of 450 nm using an automated ELISA reader (Epoch, USA). A diagnostic cut-off value of 10 IU/mL, as specified by the manufacturer (Pishtaz Teb Diagnostics, Iran) and applied in a previous study (19), was used to interpret the results. Antibody levels below this threshold were categorized as seronegative, while titers equal to or exceeding the cut-off were considered seropositive.

3.6. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 14.2. Data were analyzed with the chi-square (χ2) test and Fisher’s exact test to determine significant associations. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the analysis. Additionally, a logistic regression test was conducted to analyze the association between sex, contact with animals, and raw meat/egg consumption.

4. Results

A total of 179 psychiatric patients were included in this study. Serological analysis revealed that 76 individuals (42.5%) tested positive for T. gondii IgG antibodies, while 103 (57.5%) were seronegative (Table 1).

| Variables and Categories | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| IgG | |

| Negative | 103 (57.5) |

| Positive | 76 (42.5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 45 (25.1) |

| Male | 134 (74.9) |

| Profession | |

| Carpenter | 4 (2.2) |

| Driver | 8 (4.5) |

| Farmer | 11 (6.1) |

| Free job (unemployed/housework) | 152 (84.9) |

| Military | 3 (1.7) |

| Teacher | 1 (0.6) |

| Residential region | |

| Abyek | 8 (4.5) |

| Alborz | 47 (26.3) |

| Bouinzahra | 8 (4.5) |

| Qazvin | 84 (46.9) |

| Takestan | 32 (17.9) |

| Type of residence | |

| Rural | 45 (25.1) |

| Urban | 134 (74.9) |

| Contact with animals | |

| No | 114 (63.7) |

| Yes | 65 (36.3) |

| Consumption of raw meat/egg | |

| No | 148 (82.7) |

| Yes | 31 (17.3) |

| History of illness | |

| None | 162 (90.5) |

| Diabetes (type unspecified) | 3 (1.7) |

| Liver disease | 3 (1.7) |

| Diabetes (specified again separately) | 4 (2.2) |

| Hypertension | 2 (1.1) |

| Renal failure | 1 (0.6) |

| Thyroid disease | 4 (2.2) |

| Type of mental disorder | |

| Bipolar and related disorder | 36 (20.1) |

| Depressive disorder | 45 (25.1) |

| Obsessive compulsive and related disorder | 2 (1.1) |

| Psychotic disorders | 64 (35.8) |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic | 32 (17.9) |

| Substance abuse history | |

| No | 113 (63.1) |

| Yes | 66 (36.9) |

Abbreviation: IgG, immunoglobulin G.

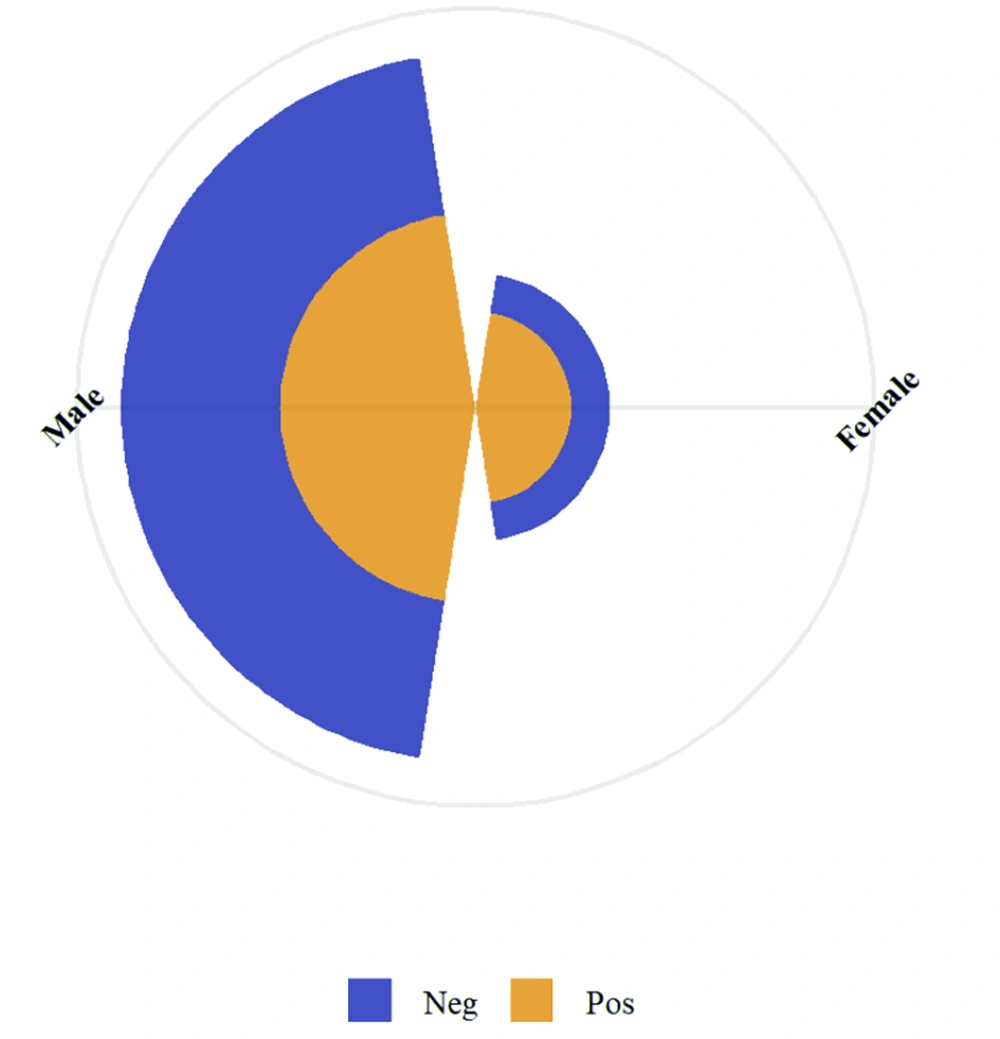

Of the total participants, 134 (74.9%) were men and 45 (25.1%) were women. The seroprevalence among males was 38.1% (51/134), while it was notably higher among females at 55.6% (25/45), indicating a statistically significant association between sex and T. gondii IgG seropositivity (χ2 = 4.221, P = 0.040) (Table 1 and Figure 2).

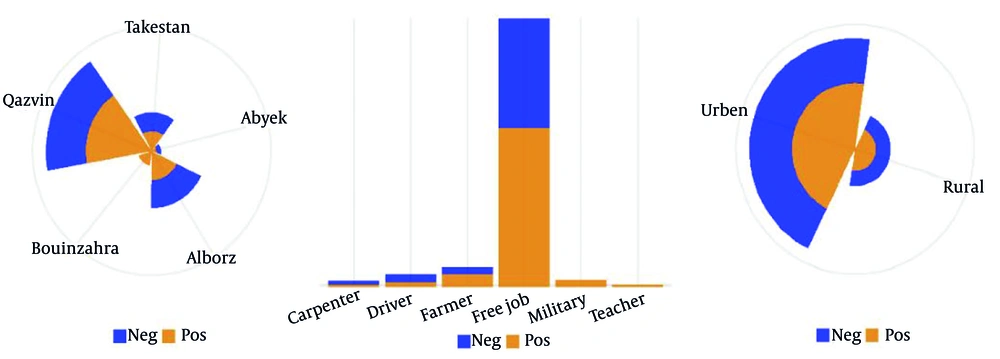

Regarding geographic distribution, the highest number of participants were from Qazvin (46.9%) and Alborz (26.3%) cities (Table 1 and Figure 3A). A significant relationship was observed between region of residence and T. gondii infection (χ2 = 13.407, P = 0.009).

Seroprevalence of latent Toxoplasma gondii infection among psychiatric patients in Qazvin province, categorized by A, residential district; B, occupation, and C, place of residence (urban vs. rural). Blue bars indicate seronegative individuals, while red bars indicate seropositive individuals.

Most participants (89.4%) were unemployed or engaged in informal jobs (Table 1 and Figure 3B). No significant association was observed between profession and T. gondii seropositivity (χ2 = 1.068, P = 0.586). Participants were predominantly from rural areas (64.8%), though no statistically significant association was found between type of residence and infection status (χ2 = 2.261, P = 0.133) (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Exposure to animals was common, with 94.4% reporting animal contact (Table 1). However, no significant correlation was detected between contact with animals and T. gondii seropositivity (χ2 = 0.247, P = 0.619). Similarly, consumption of raw meat or eggs, reported by 92.7% of participants, was not significantly associated with infection (χ2 = 0.078, P = 0.780).

A medical history of chronic diseases was reported by a minority of patients, and no significant association was found between this variable and T. gondii seropositivity (χ2 = 1.462, P = 0.917) (Table 1).

With regard to psychiatric diagnoses, 36.9% of patients were diagnosed with unspecified psychotic disorders, followed by depressive disorders (25.1%), bipolar and related disorders (20.1%), and schizophrenia spectrum disorders (17.9%) (Table 1). Although the distribution of T. gondii seropositivity varied among these groups, the association was not statistically significant (χ2 = 6.460, P = 0.091). Substance abuse history was reported in 37.4% of participants (Table 1). No significant relationship was found between substance abuse and seropositivity (χ2 = 0.636, P = 0.425).

Furthermore, in unadjusted analyses, female sex was significantly associated with higher odds of a positive IgG score [odds ratio (OR) = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.03 - 4.03, P = 0.042], while contact with animals (OR = 0.77, 95% CI: 0.41 - 1.44, P = 0.414) and raw meat/egg consumption (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.26 - 1.34, P = 0.210) were not significant predictors. When adjusted for all variables in a multivariable model, the association for female sex remained significant and largely unchanged (adjusted OR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.01 - 3.99, P = 0.047). Neither contact with animals (AOR = 0.86, 95% CI: 0.45 - 1.64, P = 0.645) nor raw meat/egg consumption (AOR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.27 - 1.45, P = 0.270) demonstrated a statistically significant association with the outcome in the adjusted model. The overall model fit was not statistically significant (Prob > χ2 = 0.115), indicating that while female sex is an independent risk factor, the combination of variables does not strongly explain the variance in IgG status (Table 2).

| Variables | OR | Standard Error | Z-Value | P-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 2.034314 | 0.7095529 | 2.04 | 0.042 | 1.026894 - 4.03005 |

| Contact with animals | 0.7720588 | 0.2447327 | -0.82 | 0.414 | 0.4147921 - 1.437045 |

| Raw meat/egg consumption | 0.5916306 | 0.2474726 | -1.25 | 0.21 | 0.2606168 - 1.343071 |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection among psychiatric patients in Qazvin province, Iran, and assessed possible associations with demographic, clinical, and behavioral risk factors. The overall seroprevalence of anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies was relatively high and consistent with previous studies conducted in various countries reporting increased exposure to T. gondii among psychiatric populations (20-23).

Our findings are also in line with several studies conducted in Iran, which have similarly reported a high seroprevalence of T. gondii antibodies among individuals with psychiatric disorders. These consistent results further support the potential association between T. gondii exposure and mental health conditions within the Iranian population (24).

Notably, a significant association was observed between sex and T. gondii seropositivity, with females exhibiting a higher infection rate than males. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting that both behavioral and biological sex-related factors may influence exposure to and immune response against parasitic infections (25-29). In particular, differences in behavioral risk factors such as food preparation practices involving raw or undercooked meat, as well as potential variations in immune system function, may contribute to the observed disparity. Nonetheless, further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the higher seroprevalence observed among females.

We found that seropositivity was also significantly associated with residential region, with higher rates observed among individuals living in Qazvin and Alborz cities. These geographic variations may be attributed to regional differences in environmental contamination, cat population density, dietary habits, and hygiene practices. Moreover, the higher proportion of participants from rural areas may still contribute to increased exposure through soil, water, and contact with animals.

Interestingly, despite high rates of animal contact and consumption of raw or undercooked meat or eggs among participants, no significant associations were found between these behaviors and T. gondii seropositivity. Several studies echo these findings: For instance, in a case-control study in Mexico, occupational exposure to raw meat among butchers was not associated with seropositivity (7% vs. 9% in controls; not significant) (30). Similarly, in rural populations in northern Iran, contact with cats showed no significant link to infection (31). In Ethiopia, despite cultural norms involving frequent raw meat consumption, raw meat intake was not significantly correlated with higher prevalence (32).

The absence of significant associations may be explained by the widespread presence of T. gondii oocysts in the environment, particularly in soil and water, which facilitates indirect transmission. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data regarding diet and animal contact may lead to exposure misclassification and reduced accuracy in identifying true risk factors (33-35).

Although a considerable proportion of participants were diagnosed with mental health disorders, no statistically significant association was identified between psychiatric diagnosis and seropositivity. Nevertheless, the observed trend supports previous evidence linking T. gondii infection with neuropsychiatric disorders, possibly due to the parasite’s neurotropic characteristics and its ability to modulate host behavior through neural and immunological mechanisms.

Several studies have indicated that psychiatric patients may exhibit higher seroprevalence rates of T. gondii antibodies compared to the general population. For example, a study conducted in China reported a significantly greater prevalence of anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies among psychiatric inpatients (3.03%) than in the general population (1.05%), with notable associations identified in conditions such as mania, schizophrenia, depression, recurrent depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder (12). Likewise, a study from Western Romania found a seroprevalence rate of 70.04% among psychiatric patients, with increasing rates observed with advancing age and among individuals living in rural areas (11).

In Ethiopia, a study demonstrated a markedly higher seroprevalence of anti- T. gondii IgG antibodies among psychiatric outpatients (33.6%) compared to control individuals (16.4%) (13). Key risk factors linked to the increased seroprevalence included cat ownership, improper disposal of cat feces, and engagement in farming activities. Similarly, research from Mexico showed that psychiatric inpatients had a higher prevalence of T. gondii infection (18.2%) than the control group (8.9%), with a significant association particularly noted among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia (1).

Similar studies have been conducted in various regions in Iran. In Fars province, the overall seroprevalence of anti-T. gondii IgG among psychiatric inpatients was 22.3% (71/318) (36). In Lorestan province, 63.5% (103/170) of psychiatric patients tested positive for IgG antibodies (37). In Sistan and Baluchestan province, 47.4% (56/118) of individuals with schizophrenia were found to be seropositive for T. gondii infection (38).

Our study has several limitations. First, the absence of a healthy control group limits our ability to determine whether the seroprevalence observed is significantly elevated compared to the general population of Qazvin province. As this was a cross-sectional hospital-based study, the findings only provide descriptive data on seroprevalence within psychiatric patients and cannot establish excess risk relative to controls. This restricts the interpretation of our results, since associations observed with demographic or clinical variables cannot be definitively attributed to psychiatric illness itself. Second, the cross-sectional design restricts causal inferences between T. gondii infection and psychiatric disorders. Third, the reliance on self-reported data for exposure variables may introduce recall or reporting bias. Lastly, the small sizes of certain subgroups (e.g., specific psychiatric diagnoses) may have limited the statistical power to detect significant associations. Despite these limitations, this study adds valuable epidemiological data to the limited literature on T. gondii infection in psychiatric populations in Iran.

5.1. Conclusions

This study provides important epidemiological data on the seroprevalence of latent toxoplasmosis in psychiatric patients in Qazvin province, northwest Iran. It underscores the need for further surveys to explore potential links and highlights the importance of prevention efforts, including food safety education and environmental sanitation interventions, especially in high-risk groups. The high incidence of infection with T. gondii, particularly among females and urban residents in certain cities, calls for greater public health interventions. Despite the absence of a direct correlation between infection and psychiatric subtypes, the prevalence observed underlines the importance of further investigation into the potential neuropsychiatric impact of T. gondii.

In light of the limitations of this cross-sectional study — such as lack of healthy controls and reliance on self-reported exposure history — future studies should employ longitudinal or case-control designs with larger sample sizes. Future research will also help clarify the potential causal relationship between T. gondii infection and mental disorders and assist in guiding prevention policies addressing both behavioral and environmental risk factors.