1. Background

According to Iran’s national census (2016), the elderly population of Iran increased from 7.27% to 8.65% from 2006 to 2016. The population aged 65 and older is projected to be 22% (more than 20 million) and that of those aged 80 and older 3.8% (around 3.5 million) of Iran’s population by 2050 (1). According to the UN, 60% of older adults have difficulty or need assistance with activities of daily living (ADL) (2). The ADL is a set of basic activities that people need to perform in their daily lives to take care of themselves (3). The results of a Swedish study showed that the most common ADL problems in nursing homes were bathing, dressing, and toileting, with incidences of 81.0%, 68.4%, and 53.1%, respectively (4). Masoumi et al. showed that many elders need help in activities such as bathing, dressing, and toileting (5). Covinsky et al. reported a strong association between the loss of independence in ADL and institutionalization, caregiver burden, higher resource use, and death (6). Cognitive impairment has a significant impact on the dependency of elders in ADL (7). Social support also plays an important role in ADL performance, so weak social support could lead to ADL dependency (8). Elders residing in nursing homes experience more loneliness, depressive symptoms, and lower quality of life (QOL) compared with community-dwelling ones (9, 10). Depression among elders in nursing homes is influenced by many factors, including the loss of independence (9). Improving ADL may be beneficial in decreasing the risk of depression among elders with cognitive impairment (11).

Life satisfaction (LS) is the degree to which someone positively evaluates his/her QOL. Life satisfaction in elders is supposed to be predicted by loneliness, personality traits, depression, mental/emotional status, and recent participation in physical activity (12). Financial status, age, social involvement, living place, functional performance, and quality of care interact with LS as well. Changes in health status and limitations in ADL are significantly related to the LS of the elderly in institutions (13). The ADL educational programs could play an important role in enhancing the independence of elders (14). The result of a systematic review showed the effectiveness of multicomponent interventions in improving ADL in the elderly (15). Van Het Bolscher‐Niehuis et al. showed the positive effect of self-management support programs on the performance of ADL in community-dwelling elderly (16). Hastaoglu and Mollaoglu showed the effectiveness of ADL education on the independence and LS of elders (17). Their program consisted of information about the old age period, nutrition, personal care, excretion, dressing, and mobility, which differs from our program. However, Cremer et al. showed that the evidence on ADL nursing interventions that affect independence is inconclusive (18).

2. Objectives

To the best of our knowledge, there is a dearth of studies about the effect of ADL training on the independence and satisfaction of older adults living in nursing homes, especially in Iran. Most of the mentioned studies have been conducted in Western countries, which differ culturally from Iran. In Iranian culture, older adults are usually cared for by their families. Recently, because of changes in family size, migration, and urbanization, the trend of transferring older adults to nursing homes has increased (19). Therefore, the present study aims to train ADL in older adults residing in nursing homes and evaluate its effect on their independence and satisfaction.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This double-blind, two-armed parallel randomized control trial was conducted to determine the effect of ADL training on the independence and satisfaction of elderly residents living in a nursing home in Karaj, Iran, from June 2018 to February 2019.

3.2. Study Participants and Sampling

All older adults residing in a nursing home (Kahrizak, Karaj) were invited, and those who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The sample size was determined based on the mean and standard deviation of a previous study (20) and the following formula: N = (Z1-α /2 + Z 1-β)2(S1 + S2)2/(µ1 - µ2)2; Z 1-α /2 = 1.96, and Z1-β = 0.85. The sample size for each group was determined to be 42 participants. The random allocation process was performed in two steps. In the generation of the random sequence step, participants were randomly allocated to one of the intervention and control groups equally. This step was done based on blocked random allocation through a computer-generated random number list using the "Random Allocation Software 1.0". In the next step, the concealment of the random allocation sequence from the participants was performed; therefore, participants did not know which group they were in until the end of the intervention. To keep the participants blinded, the duration and format of the sessions were kept the same for both groups.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Age between 60 and 80 years, ability to walk (regardless of using assistive devices such as a walker), understanding Persian, MMSE score over 21, having a problem in doing ADL (including bathing, toileting, and dressing), not having serious diseases like cancer or neurologic diseases like stroke, and willingness to participate in the study. Participants were excluded if they had critical illnesses that prevented them from participating and did not attend more than two sessions.

3.4. Intervention Procedure

Routine services provided to older adults in the nursing home include assistance with ADL, medication care, physician/nursing services, physical/occupational therapy services, and psychosocial services. No direct education about ADL was given to people in the nursing home. Both groups received routine services at the nursing home. Besides the routine services, the proper way of performing the ADL was trained in the intervention group in eight weekly group-based training sessions (each session lasted 90 minutes) directed by an expert occupational therapist. Each sub-group contained five people (a total of eight sub-groups). Group-based training was used to enhance learning. The method of training was oral representation and practical demonstration in the ADL training room, which was quiet and equipped with the required tools for ADL training. The occupational therapist practically taught the correct way of performing the ADL for the elders in their groups and also one by one if necessary. The activities taught included toileting, bathing, and dressing. These activities were chosen because they have been noted as the most common problematic activities reported by older adults (3-5). Each ADL was broken down into several tasks, and each task was divided into its component behaviors or the sequence of steps required to complete the activity. The teaching-learning techniques such as task analysis, feedback, modeling, forward and backward chaining, verbal/nonverbal prompts, and chunking were used. Cognitive strategies were also used so that the elders were provided with a metacognitive tool called goal-plan-do-check to use when thinking about and solving performance problems. Compensatory strategies and environmental adaptations/modifications such as the use of assistive devices or installation of grab bars in the bathroom/toilet were also used to ensure better ADL performance. Safety considerations were also trained to prevent hazards (Table 1). The control group received no direct ADL training. However, similar group discussion sessions (eight weekly 90-minute sessions) were held for them. The people in the control group discussed general health issues that were not relevant to ADL.

| Variables | Interventions | Control | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y; mean ± SD) | 73.95 ± 5.66 | 73.75 ± 5.90 | 0.848 |

| Gender (male/female) | 22/18 | 20/20 | 0.654 |

| Education | 0.697 | ||

| Illiterate | 37 | 35 | |

| Primary schools | 2 | 4 | |

| Diploma | 1 | 1 | |

| Marital status (married/widow) | 24/16 | 34/6 | 0.098 |

| Having a chronic disease (yes/no) | 34/6 | 33/7 | 0.762 |

| Length of stay (mo; mean ± SD) | 17.95 ± 8.82 | 18.82 ± 9.11 | 0.950 |

3.5. Data Collection Tools and Techniques

The data were collected through the Modified Barthel Index (MBI) and Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) as primary outcome measures. The MBI measures the degree of assistance required by an individual on ten common ADL items including feeding, bathing, grooming, dressing, bowel control, bladder control, toilet use, chair/bed transfer, ambulation, and stair climbing. Its total score is 100, with a higher score indicating a better ADL condition. The ten items are scored with a number of points, and then a final score is calculated by summing the points awarded to each functional skill. Tagharrobi et al. evaluated its validity and reliability in older adults dwelling in Golabchi Nursing Home in Kashan, Iran (21).

The COPM is administered through semi-structured interviews by an occupational therapist. It consists of two parts: Performance (COPM-P) and satisfaction (COPM-S). It is scored in five steps and takes about 20 - 30 minutes. In the first step, the participant is asked to specify daily activities he/she wants or needs to do, or expects to do but is not able to do. In the second step, he/she is asked to rank the importance of the activities from 1 to 10. In the third step, the participant is asked to give scores for any problem in terms of performance and satisfaction, and the total score is calculated. In the fourth step, the scoring process is repeated after the intervention. In the last step, the total performance score 1 (baseline) is subtracted from the total performance score 2 (post-intervention) and the total performance score 2 from the total performance score 3 (follow-up). In addition, the total satisfaction score 1 is subtracted from the total satisfaction score 2 and the total satisfaction score 2 from the total satisfaction score 3. Thus, the changes in performance and satisfaction scores are calculated. The validity of the Persian version of COPM was confirmed by Atashi in Iranian older adults (22).

The assessments were conducted three times (baseline, post-intervention, and three months after completing the intervention as follow-up). First, an evaluator who was blinded to the groups measured the elder’s degree of independence in ADL using MBI and their performance and satisfaction using COPM at baseline. Both groups were re-evaluated after the completion of the intervention and at follow-up. Data collection was done by an occupational therapist who was blind to the allocation of samples in the groups. The data analyzer was also blinded. Therefore, there was blinding of participants, assessors, and data analyzers.

3.6. Ethical Consideration

This randomized controlled trial was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (grant No.: PHT-9612, ethical approval code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1396.486). The trial registration on www.irct.ir is IRCT2017101136709N2. All participants filled out the informed consent form. Participants were assured that their participation in the study would not affect their quality of usual care and would not cause them any harm.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

The participants who completed the study were analyzed according to a per protocol basis. Participant characteristics were described using descriptive statistics through frequency (number and percentage), mean, and standard deviation. SPSS version 26 was used for statistical analysis using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measurements to test the effects of intervention, time (baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up), and the interaction between treatment groups and time. The normal distribution of data was confirmed through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The univariate ANOVA was used to control the effect of confounding covariates including age, gender, marital status, and education on the MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S at baseline. Effect size (ES) was also calculated using the partial eta squared. Cohen’s definition of small, medium, and large ES (ES = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively) was used (23). The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) was also calculated by dividing the difference in scores from baseline to post-intervention by the standard deviation of the change. The MCID scores greater than 3.1 for MBI (24) and greater than 2 for COPM-P/COPM-S (25) are considered a clinically important difference. A confidence interval (CI) of 95% was considered, and the significance level was set at P < 0.05. Power analysis was also used for the between-effect test about mean difference among groups. Power (1-β) greater than .80 was considered.

4. Results

Demographic characteristics, including age, gender, marital status, educational level, length of stay, and presence of chronic diseases (such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, and musculoskeletal disorders), are shown in Table 2. The mean age was 73.85 years with a standard deviation of 5.75 years. Most participants in both groups were illiterate and married.

| Weeks | Intervention Goal | Teaching Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Problem identification: Participants’ experiences and opinions about their difficulties in each ADL | Group discussion about each ADL patterns/routines, problems with each ADL, and recommendations to solve the problems |

| 2 | Task specification: Description of each ADL sub-task | Group discussion, video clip presentation, task analysis |

| 3 | Safety considerations including fall prevention techniques | Group discussion, video clip presentation, physical prompt, feedback |

| 4 | Functional mobility training including getting into/out of bathroom, and toilet | Group work, task analysis, problem solving, feedback, physical prompt, chunking, video clip presentation, modeling |

| 5 | Training the taking off/on clothes | Group work, task analysis, part-task training, problem solving, feedback, physical prompt, chunking, modeling, forward/backward chaining |

| 6 | Cognitive strategy use | Group work, using metacognitive tool called goal-plan-do-check to use when thinking about and solving performance problems |

| 7 | Compensatory strategies and environmental adaptations/modifications | Group work, using assistive devices, feedback, physical prompt |

| 8 | Reviewing the previous sessions | Group discussion, problem solving |

Abbreviation: ADL, activities of daily living.

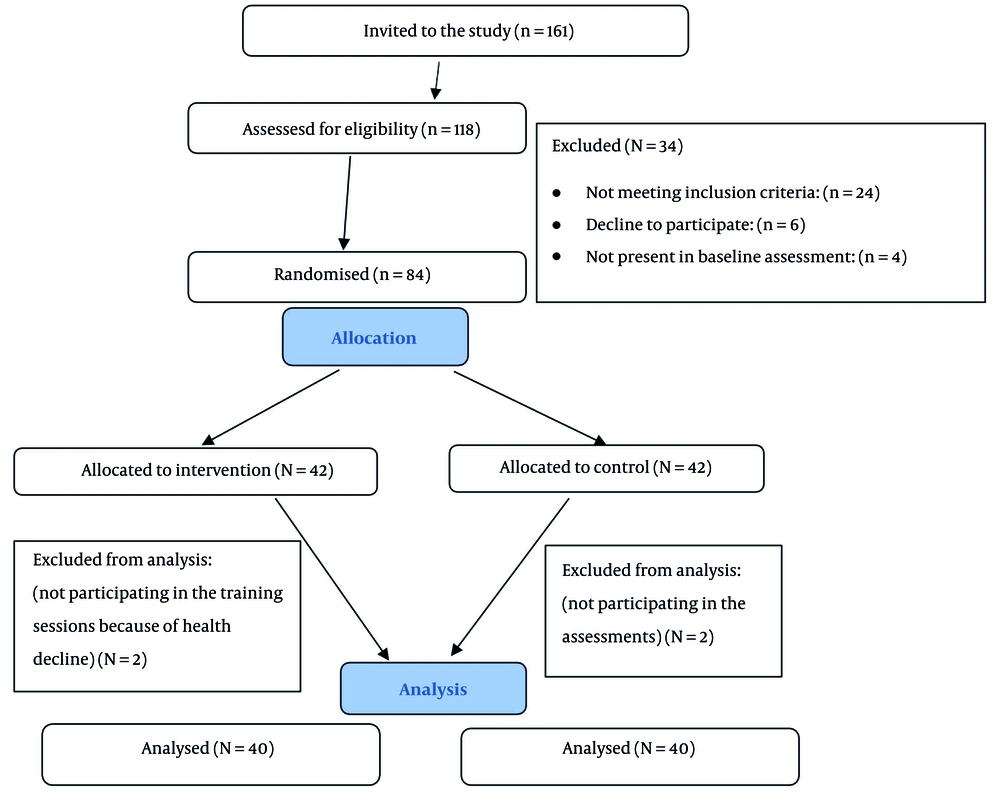

The intervention flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. All older adults residing in the nursing home (161 individuals) were invited to participate in the study, and finally, 80 participants were analyzed. The drop rate was 4.8%. Details are presented in Figure 1.

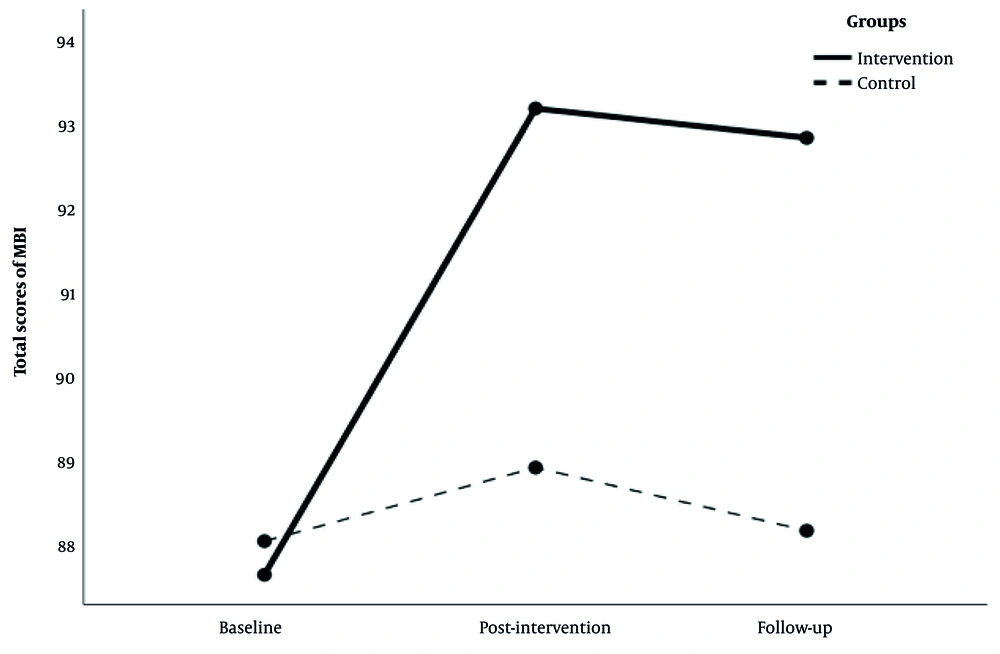

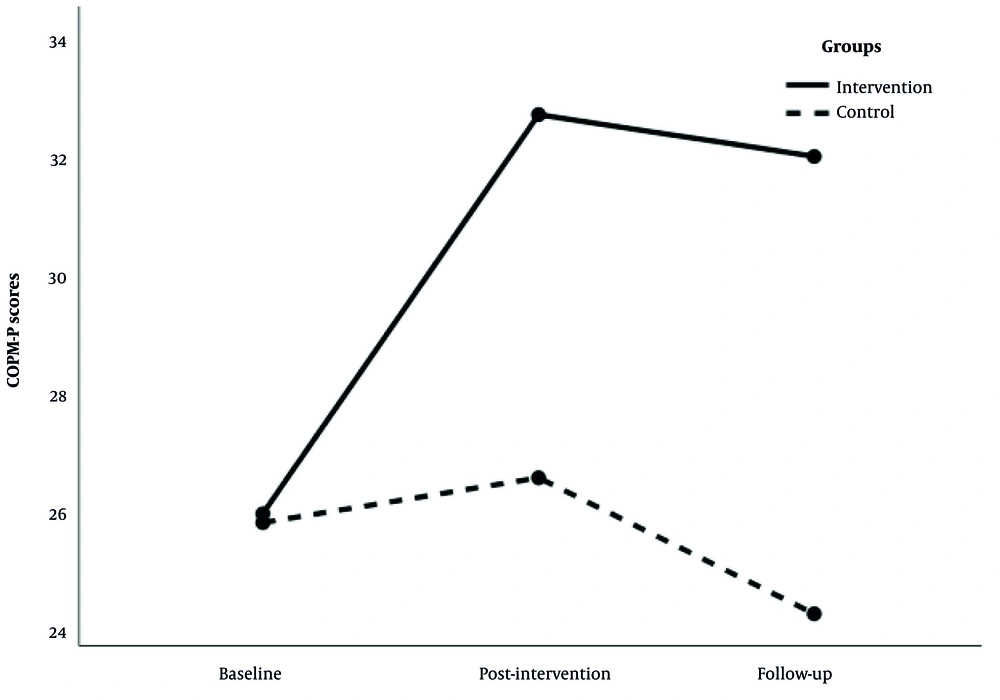

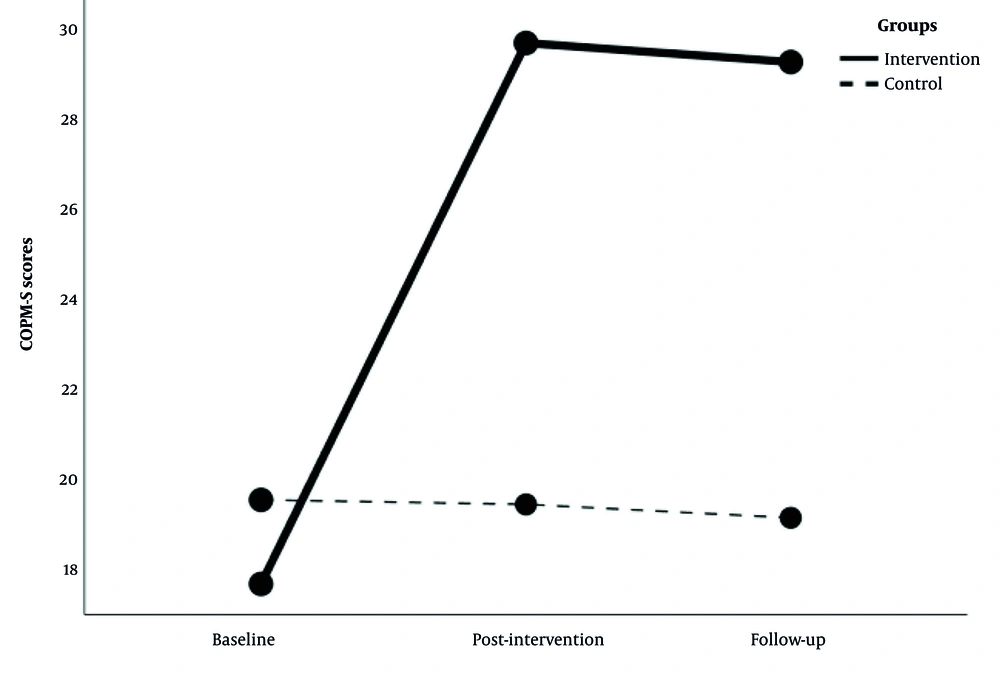

The results of the repeated measures ANOVA for total scores of MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S are shown in Table 3 and Figures 2 - 4. The results for MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S indicated a significant effect for group × time interaction (P < 0.001), time (P < 0.001), and group (P < 0.001). The between-group comparison showed that the MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S scores in the two groups were not significantly different at baseline (P > 0.05). Analysis of covariance showed no significant effect of demographic factors, including age, gender, marital status, and education, on MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S scores at baseline (P > 0.05).

| Variables | Intervention Group | Control Group | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | (95% CI) | Mean ± SD | (95% CI) | ||

| Total score of MBI | |||||

| Baseline | 87.63 ± 3.31 | (86.68 - 88.57) | 88.03 ± 2.65 | (87.07 - 88.97) | 0.477 |

| Post-intervention | 93.18 ± 2.86 | (92.29 - 94.06) | 88.90 ± 2.76 | (88.01 - 89.79) | < 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | 92.83 ± 2.84 | (91.97 - 93.68) | 88.15 ± 2.57 | (87.30 - 89.00) | < 0.0001 |

| COPM-P | |||||

| Baseline | 26.05 ± 6.73 | (23.77 - 28.33) | 25.90 ± 7.72 | (23.62 - 28.18) | 0.236 |

| Post-intervention | 32.73 ± 6.31 | (30.68 - 34.77) | 26.65 ± 6.65 | (24.61 - 28.70) | < 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | 32.02 ± 6.39 | (29.92 - 34.13) | 24.37 ± 6.96 | (22.27 - 26.48) | < 0.0001 |

| COPM-S | |||||

| Baseline | 17.65 ± 5.61 | (16.08 - 19.22) | 19.53 ± 4.28 | (17.96 - 21.10) | 0.133 |

| Post-intervention | 29.73 ± 7.23 | (27.78 -31.67) | 19.43 ± 4.90 | (17.48 - 21.37) | < 0.0001 |

| Follow-up | 29.30 ± 6.49 | (27.58 - 31.02) | 19.13 ± 4.21 | (17.40 - 20.85) | < 0.0001 |

Abbreviations: MBI, Modified Barthel Index; COPM-P, Canadian occupational performance measure-performance; COPM-S, Canadian occupational performance measure-satisfaction; CI, confidence interval.

Between-group comparison showed a significant difference in terms of MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S at post-intervention, respectively (P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.35; P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.29; and P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.38). Furthermore, a significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S at follow-up, respectively (P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.42, 1-β = 0.96; P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.25, 1-β = 0.86; and P < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.43, 1-β = 0.97).

The results showed a meaningful MCID in MBI, COPM-P, and COPM-S in the intervention group, with values of 3.135, 2.641, and 2.481, respectively. In contrast, no meaningful MCID was observed in any of the outcomes in the control group.

5. Discussion

Our results demonstrated the effectiveness of group-based training in promoting independence and satisfaction in performing ADL. According to the results, a significant difference was observed in MBI [MCID more than 3.1 (24)], COPM-P, and COPM-S scores [MCID more than 2 (25)] before and after the intervention in the intervention group. Although there was a slight decrease in these scores at follow-up, this decrease was not significant. This slight decrease may be due to a lack of practice after the completion of the study. Many therapeutic interventions that involve behavioral changes require ongoing effort and commitment from the individual. Without support, motivation, and consistent reinforcement, individuals may revert to old habits, leading to a decrease in the desired outcome (26). Unfortunately, some caregivers in nursing homes did not provide enough support and encouragement to ensure that the elders continued with their program.

The results of our study were similar to a Turkish study that showed the effectiveness of ADL training on the independence and LS of elders (17). Kahrezaie and Mirshekar showed that the QOL and the ability to perform ADL were improved in men with spinal cord injury through group training (20), which is similar to our result but with different participants. Zingmark and Bernspang and Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al. reported the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions in supporting elders to bathe independently (27, 28), which is in concordance with our result, but they just investigated one ADL (bathing). Chang et al. showed that elders receiving the self-care intervention had significant improvement in self-care activities (29), which just focused on the care part of ADL, not on the mobility part. Since the level of dependence in performing ADL increases with age (17), educational programs seem necessary to reduce the level of dependence. Therefore, it can be concluded that ADL training is beneficial without any harm. It can improve the QOL and the performance of ADL in elders. Less dependence on ADL performance may help reduce elders' problems caused by dependency, such as depression.

According to the results, a significant improvement was observed in COPM-P and COPM-S in the intervention group. Enkvist et al. found that the LS of older adults who were unable to perform ADL was lower than those who were able (30). Chang et al. showed a positive correlation between ADL performance and LS among elders in Taiwan (29). These correlational studies show that LS was well associated with independence in ADL. Increasing the level of independence in ADL can lead to a higher level of LS and QOL in elders, based on Bandura's self-efficacy theory, which states that independence is important for maintaining QOL (31). On the other hand, ADL educational programs could positively influence elders' independence levels and LS (17). Alavijeh et al. showed high self-esteem and motivation to maintain independence among the elders participating in ADL training (32), which is somewhat similar to our study. When elders improve their ability to independently perform ADL, this improvement could enhance their LS (33).

Most of the literature focuses on LS, which is different from satisfaction with ADL performance emphasized in our study. However, mediating factors such as low quality of care, age, being widowed/divorced, low level of education, low income, living alone, existence of chronic disease, hospitalization, poor perceived health, and not being visited by relatives may affect elders' dissatisfaction (6, 34), which could have affected our results as confounding factors, and we tried to control them in our study design. Therefore, ADL training not only makes the elders more independent in ADL but also increases their satisfaction with performing ADL. This satisfaction may help improve the QOL of the elders and even nursing home staff/caregivers, which requires further investigation. Furthermore, it seems that it may reduce nursing home budgets in terms of less reimbursement, less need for caregivers, reduced caregiver hours, less caregiver burden, less staff workload, and fewer resources required, which requires a cost-effectiveness study.

Given the importance of ADL training programs, it is recommended that policy-makers support educational programs and help implement these programs in nursing homes. Although there are numerous studies relevant to ADL independence and satisfaction in the elderly, this recent study is the first comprehensive interventional one in Iran in which group-based training was conducted by an occupational therapist.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the results, independence in performing ADL and satisfaction improved significantly after the intervention. Increasing the level of ADL independence could lead to a higher level of satisfaction with ADL performance in elders. Improving the independence and satisfaction of the elders could be achieved through educational programs. Thus, policy-makers are advised to support and emphasize ADL training programs to improve the performance and satisfaction of the elders.

5.2. Limitations and Recommendations

Despite the strengths of this study, it had some limitations, such as a limited sample size, a short duration of the follow-up period, and a lack of cooperation from some caregivers to encourage and support the participants to continue their program at follow-up. The participants of this study were ambulatory and cognitively healthy individuals, so it is recommended that future studies examine non-ambulatory and cognitively impaired individuals. It is also recommended that a study be conducted in which caregivers of the elderly are involved in the training program. Additionally, conducting a study on community-dwelling elders is suggested.