1. Background

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) emerged in Wuhan, China, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (1, 2). After the SARS outbreak in 2002 - 2003 and MERS in 2012, COVID-19 became the third most well-known coronavirus outbreak of the 21st century. Its clinical spectrum ranges from mild symptoms to severe pneumonia, ARDS, sepsis, and multi-organ failure (3, 4). The COVID-19 had a mortality rate of up to 2% due to extensive alveolar damage and respiratory failure (5). This rate has been reported to be higher among individuals with preexisting medical conditions (6). The COVID-19 treatment primarily relies on supportive care, including symptom control, hydration, and oxygen therapy, supplemented by approved antivirals like Ritonavir. While effective, these drugs may cause side effects and interact with other medications (7). The herbal compounds showed promising clinical benefits and reduced hospitalization costs, but inconsistent evidence limits definitive conclusions about their efficacy (8). Early in the pandemic, the musculoskeletal effects of COVID-19 received little attention. However, recent studies have reported various neuromuscular and rheumatologic complications, such as myositis, neuropathy, arthropathy, and soft tissue abnormalities (9). Bone complications related to COVID-19 remain poorly understood. The infection, corticosteroid treatment, and coagulation disorders may contribute to osteoporosis (10). Some studies also suggest a potential link between COVID-19 vaccination and musculoskeletal issues, including osteoporosis, arthritis, back pain, and myositis (11, 12).

Research on moderate to severe SARS cases has shown notable musculoskeletal, neurological, bone, and joint complications (13). Osteoporosis, the most common metabolic bone disorder, involves reduced bone density and a higher risk of fractures (14). These fractures can cause pain, disability, loss of independence, and increased mortality (15). Age and gender are key risk factors, with osteoporosis being about three times more common in Iranian women than men (318 vs. 104 cases per 10,000) (16). The disease progresses slowly and is often asymptomatic until a fracture occurs, typically in the spine, pelvis, wrist, or ribs (17). Hip fractures, in particular, are serious and can raise mortality risk up to fourfold in older adults (18). Maintaining a healthy lifestyle, including a balanced diet and regular weight-bearing exercise, is essential for preventing osteoporosis by preserving bone mass and reducing fracture risk (19, 20). Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) is the standard diagnostic tool for measuring bone mineral density (BMD), expressed as t-scores (21, 22). According to the World Health Organization classification, a t-score ≤ -2.5 indicates osteoporosis, between -1 and -2.5 indicates low bone mass (osteopenia), and ≥ -1 is normal (23). Recent studies by Creecy et al. and Wang et al. have identified a potential association between COVID-19 and decreased BMD, although further research is needed to clarify this relationship (24, 25).

2. Objectives

Given the limited data on post-COVID-19 bone complications, this study aims to assess BMD and its correlation with demographic and clinical factors in COVID-19 patients at Imam Khomeini Hospital, Urmia. We hypothesize that osteoporosis is prevalent in this population and related to specific patient characteristics.

3. Methods

The post-COVID-19 bone density study was conducted to evaluate BMD in post-COVID-19 patients at Imam Khomeini Hospital, Urmia, Iran. This descriptive cross-sectional study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. The target population consisted of COVID-19 patients over 40 years old (26) who visited the bone densitometry center at Imam Khomeini Hospital in Urmia and provided consent to participate. Patients unwilling to continue were excluded. A total of 164 participants were enrolled, based on calculations using data from Salvio et al. (27). The sample size was calculated as follows (P = 0.5, d = 0.05, and α = 0.05):

3.1. Data Collection Tools

Data were collected using a two-part questionnaire. The first section covered demographic and clinical information such as age, gender, COVID-19 history, hospitalization, pulmonary involvement, comorbidities, medications (including corticosteroid use), and oxygen therapy. The second section included reasons for densitometry, test results, relevant lab findings, and chief complaints. The checklist was developed based on prior studies and expert input from a pulmonary subspecialist, then reviewed and validated by 10 faculty members for content accuracy and relevance.

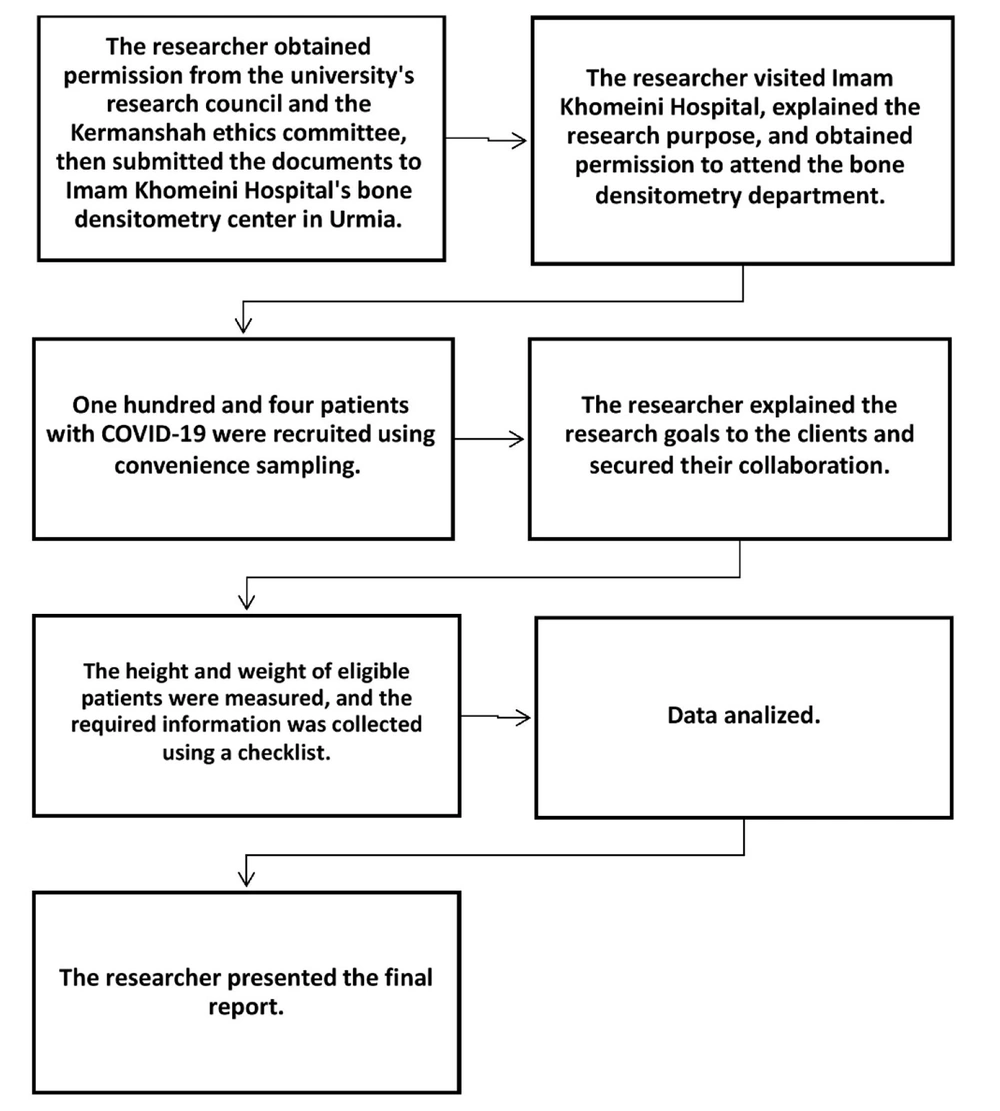

Following ethics approval, the lead researcher coordinated with Imam Khomeini Hospital officials. Using convenience sampling, 164 eligible COVID-19 patients visiting the bone densitometry center between July and December 2023 were recruited. Participants provided informed consent, after which their anthropometric data and densitometry results were recorded (Figure 1). To reduce potential bias, a validated checklist was used for data collection, and all densitometry results were interpreted by the same pulmonary subspecialist.

3.2. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed data normality. Quantitative variables were reported as means ± standard deviations, and qualitative variables as frequencies and percentages. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate associations between t-scores and qualitative variables. ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc tests were utilized to compare mean age and Body Mass Index (BMI) across osteoporosis, osteopenia, and normal bone density groups.

4. Results

The results indicate that most patients were women (89.2%). A significant 81.6% of patients received treatment on an outpatient basis. Among those hospitalized, only 5.1% required ICU admission, and 61.4% had underlying health conditions. Additionally, of the patients undergoing densitometry, only 24.1% had received cortisone treatment. The mean age of the patients was 58.86 ± 11.28 years, and the mean BMI was 29.54 ± 4.62 kg/m2 (Table 1).

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as No (%).

b Total = 158.

The results indicated that 5.06% of patients had osteoporosis in the femoral neck bone, 29.74% in the lumbar bone, and 32.27% in the radius bone (Table 2).

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| FNT-score | |

| Osteoporosis | 8 (5.06) |

| Osteopenia | 58 (36.70) |

| Normal | 92 (58.22) |

| LT-score | |

| Osteoporosis | 47 (29.74) |

| Osteopenia | 75 (47.46) |

| Normal | 36 (22.78) |

| RT-score | |

| Osteoporosis | 51 (32.27) |

| Osteopenia | 88 (55.69) |

| Normal | 19 (12.02) |

Abbreviations: FNT-Score, femoral neck t-score; LT-score, lumbar spine t-score; RT-score, radius t-score.

a Values are expressed as No (%).

According to the chi-square test, none of the variables — corticosteroid therapy, hospitalization, ICU admission, comorbidity, and gender — were significantly associated with the femoral neck, lumbar, and radius BMD in patients with COVID-19 (Table 3).

| Variables | Osteoporosis | Osteopenia | Normal | df | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNT-score | |||||

| Corticosteroid therapy | 2 | P = 0.409; X2 = 1.789 | |||

| Yes | 6 (30.0) | 26 (25.7) | 6 (16.2) | ||

| No | 14 (70.0) | 75 (74.3) | 31 (83.8) | ||

| Hospitalization | 2 | P = 0.528; X2 = 1.279 | |||

| Yes | 5 (25.0) | 16 (15.8) | 8 (21.6) | ||

| No | 15 (75.0) | 85 (84.2) | 29 (78.4) | ||

| ICU admission | 2 | P = 0.744; X2 = 0.591 | |||

| Yes | 1 (5.0) | 6 (5.9) | 1 (2.7) | ||

| No | 19 (95.0) | 95 (94.1) | 36 (97.3) | ||

| Co-morbidities | 2 | P = 0.357; X2 = 2.058 | |||

| Yes | 13 (65.0) | 65 (64.4) | 19 (51.4) | ||

| No | 7 (35.0) | 36 (35.6) | 18 (48.6) | ||

| Sex | 2 | P = 0.169; X2 = 3.561 | |||

| Female | 20 (100.0) | 90 (89.1) | 31 (83.8) | ||

| Male | 0 (0.0) | 11 (10.9) | 6 (16.2) | ||

| RT-score | |||||

| Corticosteroid therapy | 2 | P = 0.075; X2 = 5.188 | |||

| Yes | 7 (13.7) | 27 (30.7) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| No | 44 (86.3) | 61 (69.3) | 15 (78.9) | ||

| Hospitalization | 2 | P = 0.823; X2 = 0.389 | |||

| Yes | 8 (15.7) | 17 (19.3) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| No | 43 (84.3) | 71 (80.7) | 15 (78.9) | ||

| ICU admission | 2 | P = 0.561; X2 = 1.155 | |||

| Yes | 3 (5.9) | 5 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| No | 48 (94.1) | 83 (94.3) | 19 (100.0) | ||

| Co-morbidities | 2 | P = 0.927; X2 = 0.152 | |||

| Yes | 31 (60.8) | 55 (62.5) | 11 (57.9) | ||

| No | 20 (39.2) | 33 (37.5) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Sex | 2 | P = 0.580; X2 = 1.091 | |||

| Female | 44 (86.3.0) | 79 (89.8) | 18 (94.7) | ||

| Male | 7 (13.7) | 9 (10.2) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| LT-score | |||||

| Corticosteroid therapy | 2 | P = 0.941; X2 = 0.122 | |||

| Yes | 12 (25.5) | 18 (24.0) | 8 (22.2) | ||

| No | 35 (74.5) | 57 (76.0) | 28 (77.8) | ||

| Hospitalization | 2 | P = 0.478; X2 = 1.474 | |||

| Yes | 6 (12.8) | 15 (20.0) | 8 (22.2) | ||

| No | 41 (87.2) | 60 (80.0) | 28 (77.8) | ||

| ICU admission | 2 | P = 0.437; X2 = 1.655 | |||

| Yes | 1 (2.1) | 4 (5.3) | 3 (8.3) | ||

| No | 46 (97.9) | 71 (94.7) | 33 (91.7) | ||

| Co-morbidities | 2 | P = 0.138; X2 = 3.954 | |||

| Yes | 31 (66.0) | 49 (65.3) | 17 (47.2) | ||

| No | 16 (34.0) | 26 (34.7) | 19 (52.8) | ||

| Sex | 2 | P = 0.735; X2 = 0.615 | |||

| Female | 43 (91.5) | 67 (89.3) | 31 (86.1) | ||

| Male | 4 (8.5) | 8 (10.7) | 5 (13.9) |

Abbreviations: FNT-Score, femoral neck t-score; LT-score, lumbar spine t-score; RT-score, radius t-score.

a Values are expressed as No (%).

The findings showed that older patients have higher osteoporosis rates. Patients diagnosed with osteoporosis had a mean age of 68.70 ± 8.68 years, while those with osteopenia had a mean age of 58.50 ± 10.08 years. Unexpectedly, thinner patients exhibited a higher incidence of osteoporosis compared to those who were obese. Patients with a mean BMI of 27.12 ± 4.55 were found to have osteoporosis, those with a mean BMI of 29.50 ± 4.70 had osteopenia, and patients with a mean BMI of 30.94 ± 3.91 had normal bone density (Table 4).

| Variables | N | Mean ± SD | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||

| Age (y) | |||||

| Osteoporosis | 20 | 68.70 ± 8.68 | 1.940 | 64.64 | 72.76 |

| Osteopenia | 101 | 58.50 ± 10.08 | 1.003 | 56.50 | 60.47 |

| Normal | 37 | 54.57 ± 12.63 | 2.077 | 50.36 | 58.78 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Osteoporosis | 20 | 27.12 ± 4.55 | 1.018 | 24.99 | 29.25 |

| Osteopenia | 101 | 29.50 ± 4.70 | 0.468 | 28.58 | 30.43 |

| Normal | 37 | 30.94 ± 3.91 | 0.643 | 29.63 | 32.24 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

The ANOVA test revealed a significant difference in age (F (2,155) = 11.77, P = 0.000) and BMI (F (2,155) = 4.65, P = 0.011) among patients with osteoporosis, osteopenia, and those with normal bone density (Table 5).

| Variables | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | P = 0.000; F = 11.77 | |||

| Between groups | 2632.43 | 2 | 1316.21 | |

| Within groups | 17332.51 | 155 | 111.82 | |

| Total | 19964.94 | 157 | 111.82 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | P = 0.011; F = 4.65 | |||

| Between groups | 189.29 | 2 | 94.64 | |

| Within groups | 3155.85 | 155 | 20.36 | |

| Total | 3345.14 | 157 | 20.36 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

Tukey's post-hoc test showed significant age differences between patients with osteoporosis and those with osteopenia (P = 0.000), as well as between those with osteoporosis and normal bone density (P = 0.000); however, no significant difference was found between the osteopenia and normal groups (P = 0.134). For BMI, a significant difference was found between osteoporosis and normal bone density groups (P = 0.008), while no significant differences were observed between osteoporosis and osteopenia (P = 0.082) or osteopenia and normal groups (P = 0.228; Table 6).

| Dependent Variables; FNT-Scores | Mean Differences ± SE | P-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Age (y) | ||||

| Osteoporosis | ||||

| Osteopenia | 10.22 ± 2.59 | 0.000 | 4.09 | 16.34 |

| Normal | 14.13 ± 2.94 | 0.000 | 7.19 | 21.08 |

| Osteopenia | ||||

| Osteoporosis | -10.22 ± 2.59 | 0.000 | -16.34 | -4.09 |

| Normal | 3.92 ± 2.03 | 0.134 | -0.89 | 8.73 |

| Normal | ||||

| Osteoporosis | -14.13 ± 2.94 | 0.000 | -21.08 | -7.19 |

| Osteopenia | -3.92 ± 2.03 | 0.134 | -8.73 | 0.89 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Osteoporosis | ||||

| Osteopenia | -2.38 ± 1.10 | 0.082 | -4.10 | 0.23 |

| Normal | -3.82 ± 1.25 | 0.008 | -6.78 | -0.85 |

| Osteopenia | ||||

| Osteoporosis | 2.38 ± 1.10 | 0.082 | -0.23 | 4.10 |

| Normal | 1.43 ± 0.87 | 0.228 | -3.48 | 0.62 |

| Normal | ||||

| Osteoporosis | 3.82 ± 1.25 | 0.008 | 0.85 | 6.78 |

| Osteopenia | 1.43 ± 0.87 | 0.228 | -0.62 | 3.48 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

5. Discussion

This study investigated BMD and its association with demographic and clinical factors in patients with COVID-19. Our findings indicate that osteoporosis is common among older adults, consistent with Hannan et al., who reported a significant age-related decline in bone mass in the proximal femur and radius (28). Similarly, Sarafrazi et al. found a high incidence of osteoporosis in individuals aged 65 and above (29). Age-related bone loss is characterized by trabecular thinning and increased bone porosity, resulting in decreased bone density (30). These changes are further exacerbated by physical inactivity, sarcopenia, and chronic conditions such as heart failure, COPD, and cancer (31). We observed that osteoporosis was more prevalent in individuals with lower BMI, supporting findings by Fassio et al. and Premaor et al., who suggested a protective role of obesity against osteoporosis and fractures (32, 33). Qiao et al. similarly reported higher BMD in obese adults compared to those with normal weight (34). Conversely, Gkastaris et al. found increased osteoporosis prevalence with weight gain (35), potentially due to fat infiltration in bone marrow and chronic inflammation in obesity, which can adversely affect bone health (36). Promoting physical activity and healthy diets may mitigate these risks (15).

Consistent with previous literature, our study found a higher prevalence of osteoporosis among women than men. Kanis et al. reported rates of 19.3 - 23.4% in European women versus 5.7 - 6.9% in men (22), and De Martinis et al. similarly noted greater osteoporosis prevalence in women (37). This difference is largely attributable to lower peak bone mass in women and accelerated bone loss post-menopause. However, gender disparities in osteoporosis prevalence may vary across populations due to genetic, lifestyle, and dietary factors (17). The findings revealed no significant correlation between COVID-19 and osteoporosis, consistent with the results of Zhang et al.'s study (38). However, the literature is mixed. Berktas et al. reported a direct relationship between COVID-19 and osteoporosis (39), and Falbova et al. suggested that lifestyle changes during the pandemic may contribute to decreased BMD (40). Additionally, COVID-19-related inflammation and prolonged immobility have been implicated in bone loss (41). Patients recovering from severe COVID-19 may experience muscle weakness and impaired mobility, further increasing osteoporosis risk (42). Moreover, disruptions in osteoporosis management during the pandemic have led to treatment challenges and potential increases in fracture risk (43). Some clinical studies have observed increased vertebral fractures and hypocalcemia in COVID-19 patients (25, 44). The inconsistencies in findings may reflect differences in study design, follow-up duration, and sample characteristics, underscoring the need for high-quality longitudinal studies.

Finally, our study did not find a statistically significant association between glucocorticoid use and osteoporosis risk. This contrasts with prior research demonstrating that glucocorticoids, commonly used in COVID-19 treatment, can induce osteoporosis by impairing bone formation and enhancing resorption (45, 46). Corticosteroid use during COVID-19 has been associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis (39), which contrasts with our study's findings, indicating no link between corticosteroid use and osteoporosis. A plausible explanation for this inconsistency is that one-third of the patients in our study only received corticosteroids. This finding could be clarified in future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

Osteoporosis was more prevalent among older and lower-weight post-COVID-19 patients. No significant associations were found with corticosteroid use, hospitalization, ICU admission, comorbidities, or gender. These findings highlight the importance of bone health monitoring in high-risk individuals following COVID-19.

5.2. Implications for Practice

Clinicians should assess bone health in high-risk post-COVID-19 patients, particularly older adults and those with low BMI. Preventive strategies include promoting physical activity, ensuring adequate calcium and vitamin D intake, and addressing modifiable lifestyle factors.

5.3. Strengths

This is the first study to examine post-COVID-19 bone complications in the Iranian population, providing valuable insights into osteoporosis risk

5.4. Limitations

Limitations include a small sample size, short follow-up period, and potential confounding effects of medications. Future studies should involve larger cohorts, extended follow-up, and control for treatments affecting bone density.