1. Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia worldwide, representing a significant and growing global health challenge (1). Pathological changes associated with AD begin in the brain approximately a decade before the onset of clinical symptoms. Once cognitive decline reaches a threshold of severity, the condition is classified as dementia (2). The burden of AD has risen substantially in recent decades; between 1990 and 2019, the incidence and prevalence of AD and other dementias increased by 147.95% and 160.84%, respectively. The disease is pathologically characterized by the extracellular accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and the formation of flame-shaped neurofibrillary tangles composed of the microtubule-associated protein tau (3).

A major obstacle in the management of AD is the late initiation of treatment, primarily due to delays in diagnosis. Early detection is crucial, particularly in contexts where time constraints, insufficient healthcare infrastructure, and communication difficulties among patients hinder timely intervention (4). Effective diagnostic strategies are therefore essential for the early identification and management of AD. Current diagnostic approaches encompass neuroimaging techniques (5), neuropsychological assessments (6), and standardized cognitive tests (7). However, these methods often present significant limitations: Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis is invasive, neuroimaging is costly, and neuropsychological evaluations can be time-consuming. Consequently, there is an increasing need for non-invasive, cost-effective diagnostic tools that facilitate the early identification of individuals at risk for AD (8).

Although international frameworks such as the NIA-AA diagnostic criteria provide a standardized foundation for AD diagnosis, their applicability varies across regions (9). In Iran, diagnostic practices are further shaped by healthcare infrastructure constraints — such as limited access to advanced neuroimaging and reliance on outpatient psychiatric services — which underscore the importance of contextually adapted diagnostic strategies (10).

Despite the clinical significance of early diagnosis, there remains a lack of universally accepted diagnostic criteria and standardized treatment protocols for AD (11). A comprehensive and well-defined diagnostic framework is critical for tracking disease progression and optimizing treatment strategies (12). However, limited research has examined expert opinions and the effectiveness of various diagnostic modalities in distinguishing AD from other dementias (4). In clinical practice, general practitioners are often the first point of contact for patients experiencing memory impairment, yet the diagnostic and referral practices of physicians in Iran remain unclear.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the diagnostic preferences and utilization of psychological tests, laboratory analyses, and imaging modalities among Iranian healthcare professionals in the diagnosis of AD. The findings of this study may contribute to reducing the heterogeneity of diagnostic approaches and facilitating the adoption of standardized, effective strategies for early detection and intervention in AD.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Methodology

This cross-sectional expert panel survey was designed to collect and analyze opinions from specialists in neurology, psychiatry, and geriatric medicine on diagnostic approaches for AD and mild cognitive impairment. Data were gathered in a single round without iterative feedback or formal consensus measures (e.g., Kendall’s W, percentage agreement) and were analyzed using descriptive statistics to identify priority diagnostic methods and patterns of agreement among experts. A total of 150 eligible neurologists and psychiatrists were invited to participate in the study via professional networks and academic contacts. Seventy specialists completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 46.7%. A total of 70 neurologists and psychiatrists participated, offering insights into current diagnostic practices.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti Medical University (IR.SBMU.MSP.REC.1399.683) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical guidelines. All participants provided informed consent, and data anonymity was ensured.

Participants anonymously responded to a 20-item questionnaire covering three diagnostic domains: Imaging techniques [magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electroencephalography (EEG), computed tomography (CT) scan, functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)], laboratory tests [complete blood count with differential (CBC diff), serum glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase (SGOT), triglycerides (TG), serum iron, serum glutamate-pyruvate transaminase (SGPT), cholesterol (CHOL), vitamin (Vit) D3, alkaline phosphatase (ALK), fasting blood sugar (FBS), Vit B12, and thyroid function tests (TFT)], and psychological assessments [Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), clock drawing test]. Participants were asked to rank the priority of each diagnostic method on a 9-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated highest importance and 9 indicated lowest importance for evaluating patients with cognitive impairment. Participants were asked to justify responses only if they selected a score of 5 on the 9-point Likert scale, as this midpoint was assumed to reflect neutrality or uncertainty. The aim was to capture explanatory detail behind ambiguous ratings; however, we acknowledge this may have introduced variability in interpretation across respondents. Additionally, they were invited to suggest other diagnostic methods not covered in the questionnaire.

3.2. Participants

The study was conducted in 2020 and included 70 psychiatrists and neurologists specializing in AD and geriatric medicine in Tehran, each with over 10 years of clinical experience. Participants were selected using respondent-driven sampling from specialist lists at major academic hospitals in Tehran. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Specialist status in psychiatry or neurology; (2) a minimum of 10 years of clinical experience in dementia care. An initial pilot study involving 20 experts validated the questionnaire, and the final sample size was set at 50 specialists. The sample comprised 56 psychiatrists (including 44 general psychiatrists, 2 neuropsychiatrists, 7 psychosomatic psychiatrists, and 3 geriatric psychiatrists) and 14 neurologists (including 12 general neurologists, 1 multiple sclerosis specialist, and 1 epilepsy specialist). Among the participants, 66 were faculty members.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Data interpretation involved calculating mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) as well as median and interquartile range. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed that the data did not follow a normal distribution (P < 0.05). Due to the non-normal distribution (as confirmed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P < 0.05), non-parametric methods were applied. Consequently, comparisons between quantitative variables were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and the ranking of each diagnostic method was reported. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the ranks of diagnostic methods across categories. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were not performed following the Kruskal-Wallis test, as the analysis was exploratory and aimed primarily at identifying overall prioritization patterns rather than specific inter-method differences. No adjustments for confounders were required given the descriptive nature of the consensus-building design. However, consensus strength metrics (e.g., percentage agreement or Kendall’s W) were not calculated, which is acknowledged as a limitation. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 22, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

Of the 70 respondents, 56 were psychiatrists and 14 were neurologists, representing an 80:20 ratio. The demographic and professional characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Variables |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 70 (100) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 45 (64.28) |

| Female | 25 (35.72) |

| Age (y) | 10.8 ± 57.45 |

| Professional specialty | |

| Neurology | 14 (20.0) |

| Psychiatry | 56 (80.0) |

| Years of professional practice | 14.18 ± 25.28 |

| Type of workplace | |

| Academic hospital | 15 (21.44) |

| Private clinic | 30 (42.85) |

| Other healthcare setting | 25 (35.71) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

The findings of the Kruskal-Wallis test, presented in Table 2, indicate that, according to neurologists and psychiatrists, the most effective imaging modalities for the diagnosis of AD include MRI, CT scans, SPECT, EEG, PET, and FMRI. Additionally, the laboratory tests deemed most useful in AD diagnosis are TFT, Vit B12 levels, CBC diff, FBS, Vit D3 levels, SGPT, CHOL, SGOT, ALK, TG, and serum iron levels.

| Methods | Mean ± SD | Median (Interquartile Range) | Ranking | Chi-Square | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | 197.566 | < 0.0001 | |||

| MRI | 2.11 ± 2.06 | 1 (1 - 2) | 1 | ||

| CT scan | 3.80 ± 3 | 2 (1 - 7) | 2 | ||

| SPECT | 6.56 ± 2.74 | 8 (4 - 9) | 3 | ||

| EEG | 6.56 ± 3.02 | 5.8 (3 - 9) | 3 | ||

| PET | 7.94 ± 2.11 | 9 (8 - 9) | 4 | ||

| FMRI | 8.46 ± 2.65 | 9 (0) | 5 | ||

| Laboratory | 82.253 | < 0.0001 | |||

| TFT | 2.24 ± 2.38 | 1 (1 - 2) | 1 | ||

| Vit B12 | 2.29 ± 2.15 | 1 (1 - 2) | 2 | ||

| CBC diff | 2.59 ± 2.67 | 1 (1 - 3) | 3 | ||

| FBS | 3.11 ± 2.79 | 2 (1 - 4.5) | 4 | ||

| Vit D3 | 3.50 ± 2.81 | 2 (1 - 6) | 5 | ||

| SGPT | 3.74 ± 3.01 | 2.5 (1 - 7) | 6 | ||

| CHOL | 3.83 ± 2.87 | 3 (1 - 7) | 7 | ||

| SGOT | 3.84 ± 3.05 | 3 (1 - 8) | 7 | ||

| ALK | 3.86 ± 2.93 | 3 (1 - 7) | 8 | ||

| TG | 3.99 ± 2.92 | 3 (1 - 7) | 9 | ||

| Serum iron | 6.37 ± 2.80 | 8 (4 - 9) | 10 | ||

| Psychological tests | 5.770 | 0.056 | |||

| MMSE | 3.67 ± 3.01 | 2 (1 - 7) | 1 | ||

| Clock drawing test | 3.46 ± 2.96 | 2 (1 - 6.25) | 1 | ||

| MoCA | 4.87 ± 3.22 | 5.5 (1 - 8) | 1 |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalography; PET, positron emission tomography; FMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; TFT, thyroid function tests; Vit, vitamin; CBC diff, complete blood count with differential; FBS, fasting blood sugar; CHOL, cholesterol; SGPT, serum glutamate-pyruvate transaminase; SGOT, serum glutamate-oxaloacetate transaminase; ALK, alkaline phosphatase; TG, triglycerides; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

Furthermore, the analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in AD diagnosis when using the MMSE, the Clock Drawing Test, or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) psychological tests (P = 0.056). Although the P-value for psychological assessments was marginally non-significant (P = 0.056), the scores suggest a similar level of preference among MMSE, clock drawing test, and MoCA.

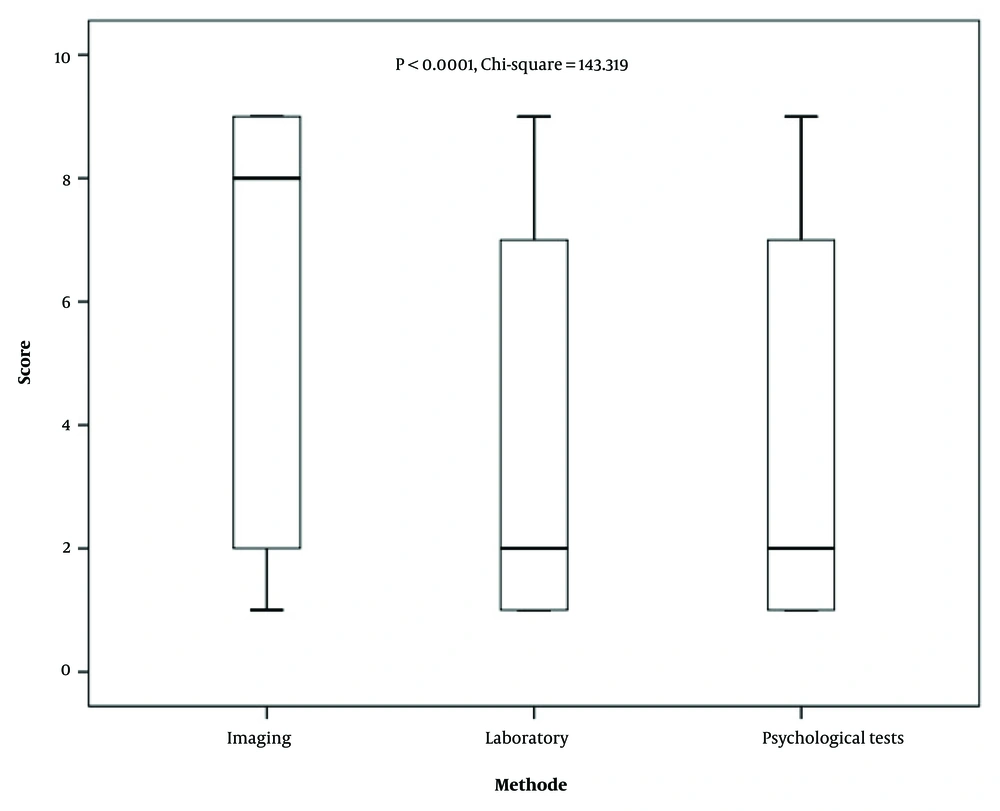

Comparative evaluation of the three primary diagnostic approaches — imaging, laboratory tests, and psychological assessments — demonstrated that, according to neurologists and psychiatrists, laboratory and psychological testing methods are the most effective for AD diagnosis, followed by imaging techniques. Figure 1 presents the relative frequency with which the three main diagnostic categories — laboratory, psychological, and imaging — were ranked as most preferred by participants. As shown, laboratory tests received the highest preference overall, followed by psychological assessments and imaging modalities.

Beyond these primary methods, additional diagnostic tools and assessments employed by neurologists and psychiatrists in this study included clinical examination, patient history, assessment of brain lobes, evaluation of family history of AD, cognitive state assessment, Adenbrook’s Cognitive Examination, verbal fluency tests, brain perfusion studies, SPECT, amyloid metabolic tracer (AMT) imaging, Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), Wechsler Memory Scale, serum Vit B1 and folic acid levels, thematic apperception test (TAT), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and serological testing for HIV, syphilis, and COVID-19. Additionally, electrophysiological tests such as electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction velocity (NCV) were also reported as part of the diagnostic process.

Several additional diagnostic tools — such as AMT imaging, MMPI, and TAT — were reported in open-ended responses. However, these were not systematically scored or ranked within the Likert framework, and thus no prioritization data or usage frequency is available.

5. Discussion

This study explored clinicians’ preferences for psychological assessments, laboratory investigations, and imaging in diagnosing dementia, with an emphasis on AD. Our aim was to propose a diagnostic approach based on consensus among neurologists and psychiatrists. The findings suggest that clinicians most often rely on laboratory tests, followed by psychological assessments and imaging, reflecting a preference for accessible and cost-effective tools that support both differential diagnosis and staging (4).

Laboratory tests were prioritized because of their practicality and ability to identify reversible contributors to cognitive impairment (13). The TFT, Vit B12 levels, and complete blood counts (CBC) were consistently highlighted as essential first-line investigations (14). This aligns with established guidelines that recommend routine screening for hypothyroidism, anemia, and nutritional deficiencies in dementia workups (15). For instance, hypothyroidism, present in a small but meaningful proportion of newly diagnosed AD cases, represents a treatable cause of cognitive decline (16). Similarly, Vit B12 deficiency is well documented among older adults and AD patients and is associated with cognitive and behavioral changes (17). The role of CBC is also noteworthy, as anemia and hematologic changes may exacerbate neurodegeneration through impaired cerebral perfusion (18). Together, these investigations support clinicians in excluding reversible etiologies and strengthening the diagnostic foundation for AD (19).

The second tier of preferred diagnostics consisted of cognitive screening tools, particularly the MMSE, the MoCA, and the clock drawing test (20). These instruments are widely recognized for evaluating cognitive status and staging dementia progression (21). Although MMSE remains common in practice, its limited sensitivity for mild impairment makes MoCA and the clock drawing test valuable complements, offering broader assessment of executive and visuospatial function (7, 22). The near-equivalent frequency of test use observed in our study suggests that clinicians employ these tools in combination rather than privileging one test exclusively (7). These results are consistent with prior research showing their utility across dementia subtypes and clinical settings, reinforcing their importance in routine workflows (23).

While laboratory and psychological assessments were prioritized, imaging was nonetheless considered an essential adjunct. The MRI was identified as the preferred modality due to its ability to reveal subtle structural changes and exclude alternative neurological conditions (24). The CT scans remained useful when MRI was contraindicated, while EEG was occasionally employed as a low-cost, accessible method for assessing disease progression or subtype differentiation (25). The reliance on structural imaging, rather than advanced modalities such as PET or FMRI, likely reflects resource constraints within Iran’s healthcare system, where access to specialized imaging is limited (26). This context helps explain the relatively lower prioritization of imaging in our findings compared with international recommendations.

When compared with international diagnostic frameworks, our results reveal both concordance and divergence. The prioritization of laboratory tests and cognitive screening aligns with routine clinical practice in many primary care and memory-clinic settings worldwide (27, 28). However, international guidelines, including the NIA-AA research framework and updated DSM-5 criteria, increasingly emphasize biomarker-driven definitions of AD, incorporating amyloid and tau assays as well as advanced imaging (29, 30). The contrast between our panel’s pragmatic preferences and guideline recommendations likely reflects two factors: Regional limitations in access to biomarker testing and the higher representation of psychiatrists in our sample, who may emphasize psychological and basic laboratory evaluations over advanced imaging.

Recent advances in blood-based biomarkers, such as plasma phosphorylated tau (31), show strong potential for accurate and accessible detection of AD pathology (32, 33). These innovations may bridge the gap between guideline recommendations and real-world practice by offering scalable diagnostic tools suitable for both resource-limited and specialized settings. As such assays and AI-assisted imaging become more widely available, clinician preferences may shift toward biomarker-based approaches, leading to greater convergence with international frameworks (34).

This study underscores that AD diagnosis extends beyond tests and imaging. Both neurologists and psychiatrists emphasized the critical role of detailed medical history and clinical examination. Key considerations include the trajectory of cognitive decline, comorbid conditions (e.g., vascular risk factors, Parkinson’s disease, prior head trauma), medication use, and family history. Documenting hereditary risk is particularly important, as rare genetic variants contribute to familial forms of AD. This holistic, patient-centered approach complements diagnostic tools and ensures that individualized care strategies are informed by both biological and contextual factors.

5.1. Conclusions

This study identified the most highly prioritized diagnostic steps for AD and mild cognitive impairment based on input from a multidisciplinary panel of experts. Cognitive screening and basic laboratory tests emerged as the top first-line approaches, underscoring the central role of practical, cost-effective, and widely accessible strategies — particularly in healthcare settings where advanced biomarker testing is not routinely available. These findings provide a clear framework for clinicians working in resource-limited environments and emphasize the value of multidisciplinary consensus in shaping diagnostic pathways. As emerging tools such as blood-based biomarkers and advanced imaging techniques become more accessible, future research should focus on integrating these modalities into structured, stepwise diagnostic protocols to enhance early detection, diagnostic accuracy, and patient care.

5.2. Strengths

This study is among the few to systematically prioritize diagnostic steps for AD and mild cognitive impairment using a structured expert consensus approach within a regional context. The multidisciplinary panel — comprising neurologists, psychiatrists, geriatricians, and neuropsychologists — enhanced the diversity of perspectives. The findings offer pragmatic, resource-sensitive recommendations that reflect real-world clinical constraints, particularly in settings with limited access to advanced biomarker testing.

5.3. Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional, single-round design lacked iterative feedback, reducing opportunities for participants to refine their responses and limiting comparability with traditional multi-round Delphi studies. No formal consensus measures (e.g., Kendall’s W, percentage agreement) were applied, restricting the ability to quantify agreement. The expert panel was drawn from a specific professional and geographic network, which may affect generalizability. Finally, the design captures expert opinion at a single time point, and results should be interpreted as indicative rather than definitive diagnostic guidelines. Future studies should adopt multi-round consensus methods and include formal agreement metrics to strengthen methodological rigor and reproducibility.