1. Background

Despite notable advancements in neonatal healthcare, many newborns worldwide continue to face serious health challenges during the first 28 days of life (1). The infant mortality rate is one of the important health indices in communities (2). In 2019, an estimated 2.4 million neonatal deaths occurred globally, equivalent to approximately 6,700 deaths per day, most of which happened within the first seven days after birth (1, 3). The most common causes of neonatal mortality include sepsis, birth-related trauma, and prematurity, which together account for nearly 75% of all neonatal deaths (4). Understanding the prevalence and associated factors of neonatal mortality is essential for implementing targeted interventions.

COVID-19 is a pandemic that has affected almost all countries, starting in 2019 in Wuhan, China (5, 6). Coronavirus disease has spread around the world and can not only be considered a health problem but also affects the global economy and the environment in various ways (7, 8). Pregnant women and their fetuses are considered high-risk populations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Pregnant women are more vulnerable during pregnancy and are at risk of contracting the disease due to their weakened immune systems and exposure to the general community (9, 10).

Globally, of the approximately 130 million infants born each year, more than 4 million die during the neonatal period, with 99% of these deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries (11, 12). Over the past three decades, the decline in neonatal mortality has been significantly slower compared to the reductions observed in under-five and post-neonatal child mortality rates (13, 14).

According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, every newborn has the fundamental right to attain the highest standard of health (15). However, recent reviews on child mortality have indicated a rising proportion of neonatal deaths during the first month of life relative to deaths among children under five years of age (16). Although approximately 40% of under-five deaths occur within the neonatal period, neonatal mortality was not originally included as a distinct target within the millennium development goals (MDGs) (17). Nevertheless, achieving the MDG target of reducing child mortality by two-thirds requires explicit attention to neonatal deaths.

The most important causes of infant mortality include premature birth and low birth weight, congenital anomalies, asphyxia or suffocation and trauma (impact), neonatal tetanus, diarrheal diseases, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and neonatal infections such as sepsis (2, 18). To adopt a targeted, evidence-based approach to reduce neonatal mortality in Iran, a clear understanding of its magnitude and contributing factors is essential.

2. Objectives

This study aims to identify the determinants of neonatal mortality among all singleton neonates admitted to Abuzar Hospital in Ahvaz during the COVID-19 pandemic in the years 2020 and 2021 (1399 - 1400 in the Iranian calendar), using institutional data from Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Setting and Population

This retrospective hospital-based cohort study was conducted to examine the records of neonatal deaths registered over a two-year period (2020 - 2021) in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Abuzar Hospital, affiliated with Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All neonatal deaths occurring within the first 28 days of life and recorded at Abuzar Hospital during the study period were included. Exclusion criteria were: Incomplete or conflicting medical records, births before 25 weeks of gestation, stillbirths (intrauterine deaths), and deaths occurring after 28 days of life.

3.3. Sampling Environment and Data Collection

Data and sampling environment were gathered from medical records across the NICU, pediatric ward, and emergency department of Abuzar Hospital. Information included neonatal admission date, age, birth weight, delivery status, diagnosis, treatments, cause of death, and comorbidities. Maternal data such as gestational age, maternal conditions, and mode of delivery were also recorded. All data were compiled using Microsoft Excel by one researcher and cross-validated for completeness and accuracy by a second researcher.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20. Quantitative variables were reported as means and standard deviations, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The chi-square test was used to assess associations between qualitative variables, while one-way ANOVA was applied for quantitative variables. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences under the code IR.AJUMS.REC.1401.433. Additionally, the confidentiality of patient data and the anonymity of personal identifiers were fully ensured and maintained throughout the research process.

4. Results

A total of 441 neonatal deaths were recorded during the years 2020 and 2021, with 224 cases in 2020 and 217 in 2021. Of the deceased neonates, 238 were male and 203 were female. Vaginal delivery accounted for 235 cases, while 206 were born via cesarean section. In terms of gestational age, 186 neonates were preterm, 250 were term, and 5 were post-term.

The blood group distribution included 70 cases with group A, 78 with group B, 25 with group AB, and the rest with group O. Among the 441 deceased, 48 had Rh-negative blood, while the remainder were Rh-positive. Parental consanguinity was present in 222 cases, while 219 were non-consanguineous.

Among the 441 deceased neonates, 150 had documented prenatal complications, including 19 with clinical jaundice, 3 with COVID-19, 12 with respiratory distress, 10 with gastrointestinal anomalies requiring surgery (esophageal atresia, imperforate anus), and 106 who required NICU admission at birth due to low Apgar scores, resuscitation, suspected infections, or prematurity.

The causes of death were as follows: Thirty-eight cases due to birth asphyxia, 22 from structural brain abnormalities, 66 from congenital cardiovascular anomalies, 59 from gastrointestinal anomalies, 28 from inherited metabolic disorders, 153 from respiratory failure, and 75 from sepsis. A total of 82 mothers had recorded pregnancy-related conditions, including 37 with gestational diabetes, 20 with pregnancy-induced hypertension, 15 with preeclampsia, and 10 with hypothyroidism.

Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of the deceased neonates. Gestational age ranged from 25 to 41 weeks, with a mean of 34.40 ± 4.15 weeks. Birth weight ranged from 500 to 4600 g, with a mean of 2346.35 ± 872.87 g. Neonatal height ranged from 30 to 65 cm, with a mean of 45.44 ± 5.73 cm, and head circumference ranged from 21 cm, with a mean of 32 ± 4.43 cm.

| Variables | Minimum-Maximum | Mean ± Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | 25.00 - 41.00 | 34.39 ± 4.15 |

| Birth weight (g) | 500 - 4600 | 2346.36 ± 872.87 |

| Birth length (cm) | 30.00 - 65.00 | 45.44 ± 5.73 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 21.00 - 45.00 | 32.00 ± 4.43 |

| Maternal age (y) | 23.00 - 44.00 | 28.96 ± 6.90 |

| Age at NICU admission (d) | 0.00 - 28.00 | 4.55 ± 7.21 |

| Length of hospital stay until death (d) | 0.00 - 28.00 | 4.67 ± 5.97 |

Age at NICU admission ranged from birth to 28 days, with a mean of 4.55 ± 7.21 days, and the duration of hospitalization until death ranged from 0 to 28 days, with a mean of 4.67 ± 5.97 days. Maternal age ranged from 23 to 45 years, with a mean age of 32.00 ± 4.43 years.

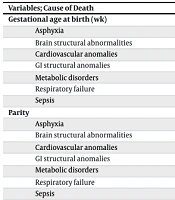

The detailed statistical findings are presented in Table 2. All causes of mortality were significantly more prevalent among neonates who required NICU admission at birth compared to those who did not, and among preterm neonates compared to term and post-term neonates (P < 0.001). Based on the results, there was a significant relationship between gestational age at birth (including asphyxia, brain structural abnormalities, cardiovascular anomalies, GI structural anomalies, metabolic disorders, respiratory failure, sepsis) and causes of neonatal death, with a mean gestational age of 35.39 ± 3.48 days (P < 0.050).

| Variables; Cause of Death | Mean ± Standard Deviation | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Gestational age at birth (wk) | < 0.001 | |

| Asphyxia | 35.12 ± 4.45 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 36.5 ± 2.68 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 36.84 ± 3.46 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 36.0 ± 2.73 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 35.39 ± 3.55 | |

| Respiratory failure | 32.15 ± 4.04 | |

| Sepsis | 35.76 ± 3.49 | |

| Parity | 0.89 | |

| Asphyxia | 2.59 ± 1.53 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 2.73 ± 2.53 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 2.36 ± 0.96 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 2.35 ± 1.59 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 2.06 ± 1.0 | |

| Respiratory failure | 2.38 ± 1.23 | |

| Sepsis | 2.43 ± 1.49 | |

| Apgar score | 0.007 | |

| Asphyxia | 5.0 ± 2.43 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 7.5 ± 1.58 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 7.33 ± 2.69 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 6.57 ± 1.88 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 4.88 ± 3.14 | |

| Respiratory failure | 6.5 ± 2.33 | |

| Sepsis | 7.11 ± 2.28 | |

| Birth weight (g) | < 0.001 | |

| Asphyxia | 2476.61 ± 810.57 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 2727.81 ± 747.5 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 2950.58 ± 734.62 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 2600.32 ± 722.87 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 2298.89 ± 708.68 | |

| Respiratory failure | 1903.35 ± 832.33 | |

| Sepsis | 2528.3 ± 815.91 | |

| Birth length (cm) | < 0.001 | |

| Asphyxia | 46.69 ± 4.57 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 45.85 ± 7.72 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 46.85 ± 5.37 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 46.85 ± 4.33 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 47.63 ± 5.9 | |

| Respiratory failure | 43.25 ± 5.7 | |

| Sepsis | 46.92 ± 5.58 | |

| Head circumference (cm) | < 0.001 | |

| Asphyxia | 32.18 ± 3.7 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 34.44 ± 3.36 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 34.13 ± 2.3 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 34.05 ± 4.06 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 32.57 ± 5.09 | |

| Respiratory failure | 30.12 ± 4.75 | |

| Sepsis | 33.03 ± 3.43 | |

| Maternal age (y) | 0.59 | |

| Asphyxia | 29.68 ± 7.24 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 30.0 ± 6.14 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 27.67 ± 5.49 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 30.59 ± 7.21 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 30.13 ± 7.16 | |

| Respiratory failure | 28.9 ± 7.36 | |

| Sepsis | 27.88 ± 6.59 | |

| Age at admission (d) | < 0.001 | |

| Asphyxia | 2.61 ± 5.26 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 5.27 ± 7.34 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 5.45 ± 7.82 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 2.88 ± 4.69 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 6.79 ± 7.95 | |

| Respiratory failure | 2.47 ± 5.78 | |

| Sepsis | 9.24 ± 8.93 | |

| Length of stay until death (d) | < 0.001 | |

| Asphyxia | 3.26 ± 3.52 | |

| Brain structural abnormalities | 7.09 ± 7.26 | |

| Cardiovascular anomalies | 3.21 ± 4.51 | |

| GI structural anomalies | 7.1 ± 7.95 | |

| Metabolic disorders | 3.57 ± 5.06 | |

| Respiratory failure | 4.72 ± 5.96 | |

| Sepsis | 4.35 ± 5.61 |

The results of this study showed that birth weight and birth length were significantly correlated with causes of neonatal death, with means of 2497.98 ± 767.49 g and 46.29 ± 5.59 cm, respectively (P < 0.050). According to the chi-square test, there were no statistically significant associations between the cause of neonatal death and the following variables: Infant sex, parental consanguinity, maternal comorbidities during pregnancy, blood group, Rh factor, mode of delivery, parity, maternal age, or year of birth (P > 0.05).

However, based on one-way ANOVA analysis, respiratory failure as a cause of death was significantly associated with lower gestational age, lower Apgar scores, lower birth weight, shorter birth length, smaller head circumference, and younger age at admission. Additionally, neonates with congenital cardiovascular anomalies died significantly earlier than those with other causes.

5. Discussion

In the present study, the frequency and causes of neonatal deaths among singleton births at Abuzar Hospital of Ahvaz, Iran, were investigated during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 - 2021. During these years, 224 cases in 2020 and 217 in 2021 were recorded, totaling 441 neonatal deaths. The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted global healthcare systems, with profound consequences for maternal and neonatal outcomes. During the pandemic, emerging evidence from tertiary care centers, including those in low- and middle-income countries, indicates a noticeable shift in both the prevalence and causes of neonatal mortality among hospitalized infants.

In the present study, 238 neonates were male and 203 were female. The results showed that vaginal delivery accounted for 235 cases, while 206 were born via cesarean section. In Ghaem Hospital, Boskabadi et al. studied the causes and predisposing factors in neonatal mortality (19). The results of their study showed that of 1630 hospitalized neonates in this center, 162 (9.94%) died, and 63% of them weighed less than 1500 g (19). Mehrkas et al. in 2020 studied the causes of deaths and mortality rates among hospitalized children in Isfahan, Iran (20). They reported that the rate of mortality was higher in hospitalized boys than in girls (P < 0.050) (20). Also, in their study, the rate of mortality among hospitalized children was higher in natural births than in cesarean sections (P < 0.050) (20). The findings of the present study are similar to the aforementioned study.

In a similar study in northeastern India by Kataki et al., over a two-year period, the overall hospital death rate was higher in boys. The results of the present study regarding the causes of hospital mortality in hospitalized children are similar to previous studies (21).

According to the results, the number of neonates in terms of gestational age recorded as preterm, term, and post-term were 186, 250, and 5, respectively. Regarding Apgar scores at birth: One neonate had a score of 0, 7 had a score of 1, 7 had a score of 2, and 15 had a score of 3 — all of whom required resuscitation at birth. Additionally, 13 neonates had a score of 4, 12 scored 5, 55 scored 6, 50 scored 7, and the remaining had scores of 8 or higher.

A total of 82 mothers had recorded pregnancy-related conditions, including 37 with gestational diabetes, 20 with pregnancy-induced hypertension, 15 with preeclampsia, and 10 with hypothyroidism. Among the 441 deceased neonates, 150 had documented prenatal complications, including 19 with clinical jaundice, 3 with COVID-19, 12 with respiratory distress, 10 with gastrointestinal anomalies requiring surgery (e.g., esophageal atresia, imperforate anus), and 106 who required NICU admission at birth due to low Apgar scores, resuscitation, suspected infections, or prematurity.

The blood group distribution included 70 cases with group A, 78 with group B, 25 with group AB, and the rest with group O. Among the 441 deceased, 48 had Rh-negative blood, while the remainder were Rh-positive. Parental consanguinity was present in 222 cases, while 219 were non-consanguineous.

The causes of death were as follows: Thirty-eight cases due to birth asphyxia, 22 from structural brain abnormalities, 66 from congenital cardiovascular anomalies, 59 from gastrointestinal anomalies, 28 from inherited metabolic disorders, 153 from respiratory failure, and 75 from sepsis.

Based on the study reported by Boskabadi et al., the major causes of neonatal mortality were severe prematurity (less than 32 weeks) at 57.4%, asphyxia (5-minute Apgar less than 6) at 30.86%, congenital anomalies at 27.16%, infections at 25.3%, respiratory complications at 24.7%, hematologic disorders at 6.8%, and cerebral disorders at 6.2% (19). The results of this study were similar to those of the Boskabadi et al. study 19.

In Hamadan province, the rate and causes of neonatal mortality were investigated by Oshvandi et al. (22). Based on their study, the most frequent causes of neonatal death were respiratory distress syndrome at 55.5%, sepsis at 10.2%, asphyxia at 8.7%, congenital anomalies at 6.6%, and DIC at 5.7%. The least frequent causes were hypoglycemia at 0.3% and convalescence at 0.9%. They found a relationship between birth weight (P = 0.002), gestational age (P = 0.001), infant age (P < 0.001), maternal age at delivery (P < 0.001), and congenital abnormality (P < 0.001) with the cause of death (22), which is similar to the results of our study.

Mehrkash et al. reported that the most common cause of hospital deaths in children was infections, followed by heart disease (20), which shows that the results of the present study are also consistent. The most common global causes of neonatal mortality include complications related to preterm birth (such as respiratory failure), birth trauma (asphyxia), infectious diseases (e.g., pneumonia, tetanus, diarrhea, sepsis), and congenital and metabolic disorders. Similarly, in the current study, respiratory failure due to prematurity was the leading cause of death, accounting for 153 cases (34.69%).

In countries like Iran, where regional hospitals such as Abuzar Hospital in Ahvaz serve as referral centers for critical neonatal cases, the burden was particularly acute. The pandemic led to increased delays in maternal referrals, reduced access to timely obstetric and neonatal care, and resource constraints in NICUs. Globally, approximately 2.8 million neonates die each year, with 73% of these deaths occurring during the first week of life (11). In line with global data, the present study found that the mean age at NICU admission was 4.55 ± 7.21 days, and the mean duration of hospitalization until death was 4.67 ± 5.97 days (11). These findings are consistent with reports from WHO and UNICEF, which highlight the vulnerability of neonatal care systems during global emergencies.

Congenital anomalies are another major cause of neonatal death, accounting for 5% to 38% of total neonatal deaths worldwide (23). In high-income countries, the proportion of deaths due to congenital anomalies is higher than in low-income settings, primarily because advanced antenatal care has successfully reduced other preventable causes of neonatal mortality (24, 25). For example, in low-income countries, birth asphyxia accounts for approximately 25% of neonatal deaths, and 98% of all global asphyxia-related deaths occur in these countries (26, 27). In our study, 147 cases (33.3%) were due to congenital anomalies — including cardiovascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal defects — while 8.62% were attributed to asphyxia. These findings suggest that Iran's neonatal mortality profile resembles that of high-income countries.

Neonatal infections, including sepsis, also represent a substantial portion of deaths in low- and middle-income countries — around 27% — whereas in high-income nations, they account for only 3.4% of neonatal deaths (28, 29). In the present study, sepsis was responsible for 75 deaths (17%), aligning Iran more closely with developing countries in this regard. Notably, the potential impact of COVID-19 on neonatal mortality cannot be ignored, as several deaths were associated with neonatal COVID-19 infection. The results of this study showed that respiratory failure was more common in neonates with lower gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score, height, and head circumference at admission.

Overall, my results likely reflect a confluence of pandemic-associated factors, including maternal COVID-19, healthcare strain, and established neonatal vulnerabilities. Comparisons with national registry data and similar regional studies underscore persistent themes but also highlight a potential elevation in mortality at medical centers like Abuzar Hospital during the pandemic.

5.1. Conclusions

Neonatal mortality remains a significant public health concern, with respiratory failure identified as the most common cause of death among newborns. Considering the high prevalence of premature death in infants less than 37 weeks of gestation, more attention should be paid to the control of preterm delivery in order to prevent respiratory distress syndrome and birth asphyxia. This condition is especially prevalent in high-risk neonates, highlighting the urgent need for targeted preventive measures, strengthening NICU infrastructure and staffing, ensuring uninterrupted access to essential neonatal medications and equipment, integrating maternal-neonatal care with infectious disease preparedness, and improving clinical interventions to reduce mortality rates associated with neonatal respiratory complications.

5.2. Strengths

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed critical vulnerabilities in maternal and neonatal healthcare delivery, particularly in low-resource and high-demand settings. Addressing these challenges through policy, infrastructure, and clinical innovation will be essential to improving neonatal survival in both routine and crisis settings.

5.3. Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that this study was conducted in a single hospital in Ahvaz, which limits the generalizability of the findings to the national level. Furthermore, the data pertain to the COVID-19 pandemic period, during which many mothers may have avoided hospital visits due to fear of infection. This may have influenced the overall mortality profile and must be considered when interpreting the results. Hence, further multicenter studies across the country are strongly recommended to validate and expand upon these findings.

5.4. Confounding Factors

Many confounding factors can affect infant mortality. These include maternal factors, infant factors, and environmental factors. Some maternal risk factors include the young age of the mother, smoking during pregnancy, inadequate care during pregnancy, not breastfeeding the baby, and alcohol or drug use. Infant-related factors include low birth weight and premature birth, as babies born before their due date often have more health problems and are at higher risk of death. Some babies are born with birth defects that can lead to their death, and respiratory and other infections can also increase the risk of infant mortality. In addition, environmental factors can be dangerous, such as babies sleeping on their stomachs, sleeping on soft surfaces (such as pillows or sharing a bed), and overheating, which can lead to SIDS. Finally, poverty, lack of access to health and education services, and other social problems can affect infant mortality.