1. Context

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) when the virus enters and attacks the immune system (1-4). The disease is classified as AIDS when the number of CD4+ T-cells falls below 200 cells per microliter of blood (5). The HIV is mainly transmitted through sexual intercourse, including unprotected anal transmission, contaminated blood, and infected needles, as well as from mother to child during pregnancy and childbirth (6). Excretions from body fluids such as saliva and tears are capable of transmitting HIV infection. Safe sex practices and alternatives to syringes may be solutions to prevent the spread of this disease (7).

The virus is completely destroyed by drying blood infected with HIV. However, transmission can occur with a contaminated syringe because anticoagulant factors used in the syringe and its head prevent the blood from drying and keep it fresh, allowing the virus to persist (8). Antiviral therapy reduces the likelihood of mortality and complications associated with this disease; however, these medications are costly and may lead to adverse effects. Genetic research indicates that HIV initially mutated in West Africa during the early 20th century (9).

The AIDS was first recognized by the centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) in 1981, while the causative agent of HIV infection was identified earlier that decade (10). Since its discovery, AIDS has killed 30 million people by 2009. As of 2010, around 34 million individuals have been diagnosed with AIDS (11). The AIDS is known as a global epidemic, which is currently very widespread and expanding. The AIDS has significantly influenced societies, both as a medical condition and as a source of discrimination (12). Additionally, there are potential economic impacts that warrant attention. Numerous misconceptions exist regarding AIDS, such as the belief that it can be transmitted through daily living with people living with HIV (13).

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This study was conducted on December 25, 2024, to evaluate the transmission, prevention, and treatment of the HIV virus. Search databases such as Google Scholar, Science Direct, CINAHL, Web of Science, and PubMed were used to find original articles in this field. The review of the epidemiological literature was conducted in the English language. All pertinent studies published between 1990 and 2024 were identified. A total of seven hundred articles were retrieved from the databases.

2.2. The Exact Search Strings and Keywords

The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) utilized in this research included terms such as 'AIDS', 'HIV Virus', 'Chronic Disease', and 'Infection'. Absolute keywords for article searches were ((("AIDS" [Title/Abstract]) AND ("HIV Virus" [Title/Abstract])) AND ("Chronic Disease" [Title/Abstract]) AND ("Infection" [Title/Abstract])) AND ("Health" [Title/Abstract])).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The criteria for entering this narrative review were only articles with the following characteristics:

- Articles whose full text is available

- Articles that are only about the HIV virus

- Articles that have evaluated symptoms, ways of transmission, prevention, and treatment of the HIV virus

- Articles that are only published in English or Persian

However, articles that meet the following criteria were excluded from the review:

- Books

- Presentations (PowerPoint)

- Conference articles

- Letters to the editor

- Review articles

2.4. Literature Search (Date Ranges and Number of Articles Found in Each Database)

The review period was restricted to the years 1990 to 2024 to enhance the efficiency of the study evaluations. Research indicates the symptoms, transmission methods, prevention strategies, and treatment options for the HIV virus in humans. Table 1 presents the results of the queries from various databases. The databases employed for the literature search comprised Google Scholar, Science Direct, CINAHL, Web of Science, and PubMed. In relation to studies addressing the transmission, prevention, and treatment of the HIV virus, a total of 99 articles were retrieved from Science Direct, 67 articles from the Web of Science database, 55 articles from PubMed, 111 articles from Google Scholar, and 60 articles from the CINAHL search engine (Table 1).

| Terms | PubMed | Science Direct (Scopus) | CINAHL | Web of Science | Google Scholar | Unique Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIDS | 15 | 28 | 16 | 20 | 36 | 115 |

| HIV virus | 16 | 22 | 13 | 17 | 23 | 91 |

| Chronic disease | 13 | 26 | 19 | 13 | 12 | 83 |

| Infection | 11 | 23 | 12 | 17 | 40 | 103 |

| Total | 55 | 99 | 60 | 67 | 111 | 392 |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

2.5. Study Selection Process

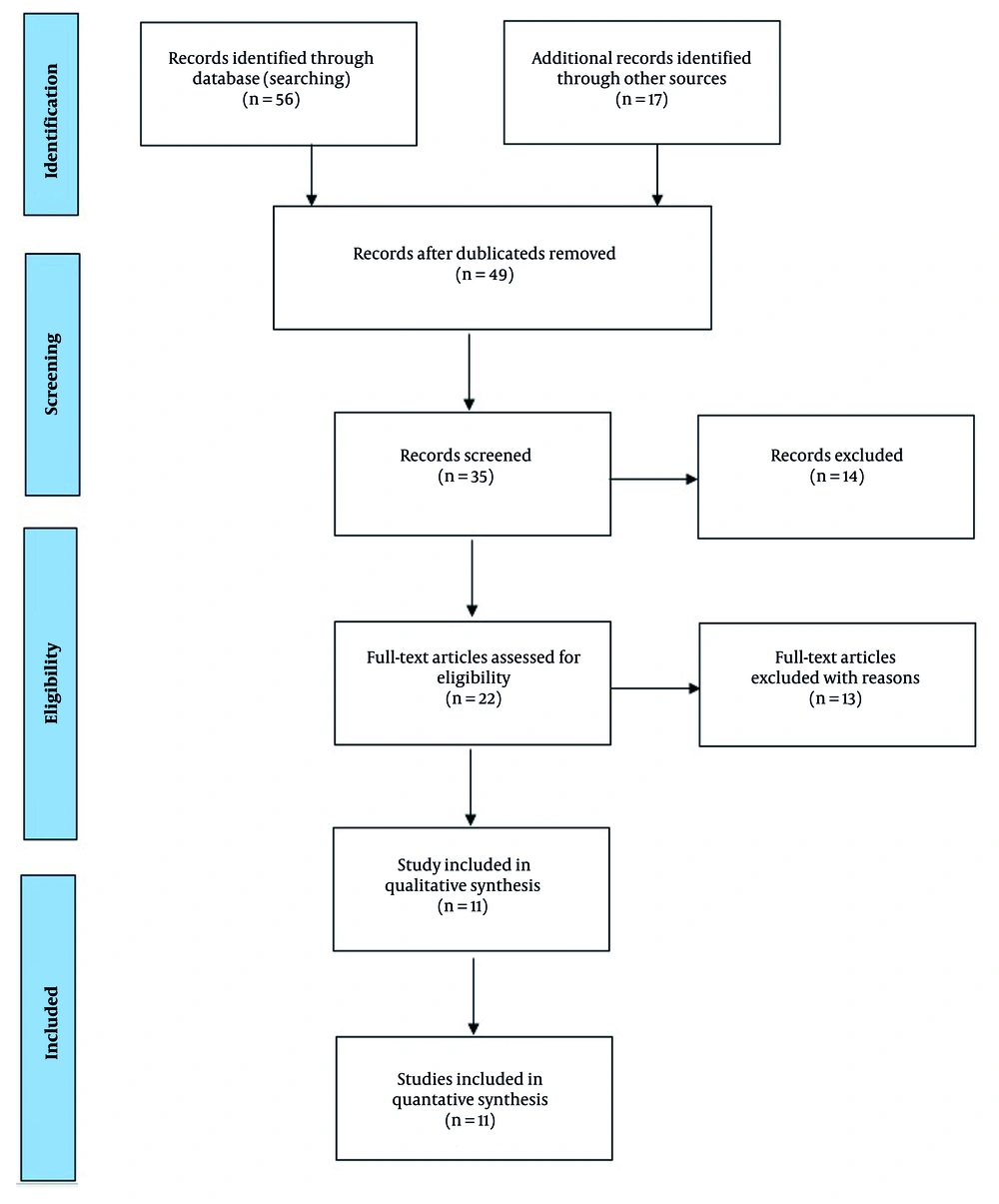

Based on the aforementioned criteria, an initial screening of 392 published titles was conducted. Screening and selection were performed by two independent reviewers, with conflict resolution. Out of these, 56 and 17 articles were identified and selected based on records found through database searches and additional sources. In the subsequent stage, 49 studies were reviewed, leading to the inclusion of 35 full-text articles in the analysis process. A total of 14 articles were deleted, along with an additional 22 articles during the secondary studies, resulting in 11 articles ultimately entering the analysis process. All relevant studies published between 1990 and 2024 were identified. Figure 1 illustrates the preparation of studies and the selection process of articles according to the PRISMA flow diagram.

2.6. Data Collection Process

Suitable articles were evaluated based on inclusion and exclusion criteria in terms of title and abstract. Then, the full text of the eligible articles was screened independently by different colleagues, and the data were extracted and recorded in the data collection form as follows:

- First author

- Research date (year of article publication)

- State

- Statistical analysis method

- The HIV virus

- The AIDS

- Chronic disease

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Signs and Symptoms of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

The HIV infection has three main stages: Acute infection, latent period, and AIDS (14). The initial phase of HIV infection is referred to as acute HIV infection or acute "retroviral" syndrome (15). Many people develop illnesses such as pseudo-influenza or pseudo-mononucleosis 2 to 4 weeks after being exposed to this disease, while others do not have any notable symptoms. Symptoms manifest in 40 to 90 percent of instances and typically encompass fever, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, skin itching, headache, or oral and genital ulcers. Skin itching, which occurs in 20 to 50% of cases, appears on the upper body and is maculopapular (16). Additionally, at this stage, some people get opportunistic infections. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, may manifest, and neurological symptoms such as peripheral neuropathy or Guillain-Barre syndrome may also arise (17). The length of these symptoms can differ, typically lasting one to two weeks. Due to their nonspecific nature, these symptoms are frequently overlooked as indicators of HIV infection. Even instances observed by a family or hospital are often misidentified as various common infectious diseases that share similar symptoms (18). Therefore, it is appropriate to consider HIV infection in patients who have predisposing factors (19).

3.2. Incubation Period of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

The period of HIV chronic infection can last from about three years to more than 20 years (on average about eight years) without any treatment, depending on the strength of the person's immune system (20). Although there are usually no symptoms at the beginning of the disease, there are very few symptoms. However, as this stage approaches its conclusion, numerous individuals encounter symptoms such as weight loss, digestive issues, fever, and muscle pain (21). Also, 50 to 70 percent of people develop persistent lymphadenopathy, in which several groups of lymph nodes (except in the groin) are painless and unexplainably enlarged for more than three to six months (22). If not treated, the course of the disease will ultimately result in AIDS; however, a small fraction of individuals (approximately 5%) sustain their elevated levels of CD4+ T-cells for more than 5 years without any antiviral treatment (23). These people are classified as HIV controllers, and those who maintain a low or undetectable amount of virus in their bodies without antiretroviral therapy are known as "superior controllers" or "superior suppressors" (24).

3.3. Ways of Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus

The HIV is primarily transmitted through three main routes: Sexual contact, exposure to infected blood or tissue, and transmission from mother to child during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding, a process referred to as vertical transmission (25). There is no risk of the virus being transmitted via feces, nasal secretions, saliva, phlegm, sweat, tears, urine, or vomit unless these fluids are contaminated with blood (26). The predominant method of HIV transmission is sexual contact with an infected individual (27). The majority of HIV transmission cases globally occur through contact between individuals of the opposite sex (28). However, the predominant route of transmission varies from country to country. In the United States, as of 2009, most sexually transmitted HIV infections have occurred among gay men, accounting for 64% of all observed cases (29).

The estimated likelihood of HIV transmission during unprotected sexual contact between individuals of the opposite sex is four to ten times greater in low-income nations compared to high-income nations. In low-income countries, the estimated risk of female-to-male transmission is 0.38% per sexual intercourse, while the risk from male to female is estimated at 0.30% per sexual act. In contrast, in high-income countries, these estimates are significantly lower, with rates of 0.04% for female-to-male transmission and 0.08% for male-to-female transmission (30).

Furthermore, the risk associated with anal intercourse is notably higher, estimated to be between 1.4% and 1.7% per act of intercourse, whether with the opposite or same sex. Although the risk of transmission through oral sex is relatively low, it has been described as "close to zero", although a few cases have been reported (31). The risk of infection through oral sex is estimated to be zero to 0.04%. In public settings, such as with prostitutes, there is a risk of transmission from female to male (32). The presence of genital ulcers appears to increase the risk of infection by approximately five times. Other sexually transmitted diseases, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and bacterial trichomonas vaginosis, increase the risk of transmission to a lesser extent (33). In the final stages of a person's HIV infection, the rate of transmission becomes approximately eight times higher. Rough sexual activity may also be an effective factor in increasing the risk of transmission (34).

A comparison of transmission modes by region is presented in Tables 2 - 4, utilizing recent UNAIDS data. The first country listed is Eswatini, which has the highest HIV prevalence rate, with a prevalence of 19.58% (Table 2). Eswatini is located in southern Africa and has a population of about one million people, of whom 200,000 are living with HIV (35). Table 2 shows that Lesotho is the second country reporting the highest HIV prevalence rate, with a prevalence of 18.72% (Table 2). Lesotho is also one of the southernmost countries in southern Africa, with a population of about two million people, of whom approximately 374,000 are living with HIV. Botswana ranks third, with a prevalence of 15.75%, while South Africa has a prevalence of 14.75%. Namibia is the fifth country, with a prevalence of 8.9% (Table 2). Zimbabwe is the sixth country with the highest HIV rate, with a prevalence of 8.7%. Mozambique has an HIV prevalence of 8.21%, and Zambia has an HIV prevalence of 6.9% (Table 2). Malawi is the ninth country with the highest HIV rate, at a prevalence of 5.69%. Finally, Equatorial Guinea rounds out the top ten countries with the highest HIV rates, with a prevalence of 5.18% (36).

| Country (Territory or Area) | Eswatini | Lesotho | Botswana | South Africa | Namibia | Zimbabwe | Mozambique | Zambia | Malawi | Guinea | Iran |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV rate | 19.58 | 18.72 | 15.75 | 14.75 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 8.21 | 6.9 | 5.69 | 5.18 | 0.3 |

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

a Values are expressed as percentage.

Table 3 presents the rates of AIDS cases in women and men according to the most significant transmission methods in different countries, territories, or areas, based on recent UNAIDS data (38). Transmission by blood includes several routes, such as the sharing of syringes for injecting drugs like heroin, injuries caused by needle penetration, transfusion of contaminated blood or blood products, or injections administered with unsterilized medical equipment (Table 3) (39). The risk of transmission from a needle stick injury from an infected individual is estimated to be 0.3% per incident (approximately one in 333 practices), whereas the risk associated with mucosal contamination from contaminated blood is estimated at 0.09% per incident (approximately one in 1,000 practices) (38).

| Area and Country (Territory or Area) | Sex Between Men | Injecting Drug Users | Heterosexual | Mother to Child Transmission | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | Female | Male | Total | |

| EU/EEA | |||||||||||

| West | 7,842 | 7,886 | 196 | 641 | 840 | 4,668 | 3,349 | 8,044 | 130 | 113 | 243 |

| Centre | 1,670 | 1,674 | 47 | 142 | 189 | 945 | 1,327 | 2,272 | 30 | 45 | 75 |

| East | 2,921 | 2,921 | 2,420 | 14,304 | 16,724 | 26,968 | 30,304 | 57,272 | 160 | 137 | 297 |

| Total WHO European Region | 12,433 | 12,481 | 2,663 | 15,087 | 17,753 | 32,581 | 34,980 | 67,588 | 320 | 295 | 615 |

The estimated prevalence of HIV infection among children and adults in different regions of the world — including South and Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America, North America, East Asia, and Western and Central Europe — were 3.6 million to 4.5 million, 1.3 million to 1.7 million, 1.2 million to 1.7 million, 1.0 million to 1.9 million, 580,000 to 1.1 million, and 770,000 to 930,000, respectively (Table 4). Additionally, Table 4 shows that the estimated mortality rates among children and adults in South and Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America, North America, East Asia, and Western and Central Europe were 250,000, 90,000, 67,000, 20,000, 56,000, and 9,900, respectively (Table 4).

| Country (Territory or Area) | South and Southeast Asia | Eastern Europe and Central Asia | Latin America | North America | East Asia | Western and Central Europe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated prevalence of HIV infection (children and adults) | 3.6 - 4.5 million | 1.3 - 1.7 million | 1.2 - 1.7 million | 1.0 - 1.9 million | 580,000 - 1.1 million | 770,000 - 930,000 |

| Estimated mortality rate of children and adults | 250,000 | 90,000 | 67,000 | 20,000 | 56,000 | 9,900 |

| Prevalence in adults (%) | 0.3% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Transmission by blood is possible through the use of a common syringe for injecting drugs such as heroin, a wound due to the penetration of the needle head, transfusion of contaminated blood or blood products, or injections that are performed using unsterilized medical equipment (37). The risk of transmission from the needle stick of an infected person is estimated to be 0.3% per practice (about 1 in 333) and the risk of mucosal contamination from contaminated blood is estimated to be 0.09% per practice (about 1 in 1,000) (39).

In 93% of cases involving the use of infected blood in blood transfusions, the infection will be transmitted. In developed countries, the risk of contracting HIV through blood transfusion is very low (less than one in five hundred thousand), and HIV testing is conducted on donor blood (40). As of 2008, about 90% of pediatric HIV cases are accounted for by vertical transmission. With proper treatment, the risk of infection from mother to child can be reduced to about 1%. Treatment through prevention includes the use of antiviral medications by the mother during pregnancy and childbirth, timely caesarean section (rather than emergency), avoidance of breastfeeding, and the administration of antiviral drugs to the infant. Nevertheless, numerous such resources are lacking in developing nations. If food is contaminated with blood during teething, it can increase the risk of transmission (41). Figure 2 shows the ways of transmission of the HIV virus.

3.4. Diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus

According to the occurrence of the patient's signs and symptoms, it is diagnosed through testing and laboratory checks. The HIV testing is recommended for everyone at risk, including anyone with any type of sexually transmitted disease (42). Severe malfunction of the immune system is revealed. Three or six months after the last high-risk behavior or event is considered in the disease diagnosis period, meaning the high-risk behavior should be abandoned, and no other high-risk event should occur. The test should be performed three to six months after the last high-risk behavior or event. The period when the virus entered the person's body, but the test results are negative because a sufficient amount of antibody was not secreted in the person's blood, is called the window period (43).

3.5. Prevention of Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Regular use of condoms in the long term reduces the risk of HIV transmission by about 80% (44). Some evidence shows that the female condom can provide the same level of protection (45). Whether this protects male-to-female transmission is controversial (46). Women who are circumcised are at increased risk of HIV transmission. Programs that encourage abstinence do not appear to be effective against HIV risk (47). The evidence suggests that bilateral training is equally weak. Sex education in schools can reduce risky behavior. A significant minority of young people, although aware of the dangers of HIV and AIDS, still engage in risky activities. The use of zidovudine alone reduces the risk of HIV infection through syringe injection by five times. This treatment is recommended after rape and when the rapist is known to have HIV (48). But when HIV status is unknown, current treatment plans usually involve Lepinavir/ritonavir and lemiidine/zidovudine or tenofovir/emtricitabine, which can further reduce the risk (49). So far, no effective vaccine for AIDS has been discovered. Although there have been advances in the design, initial production, and initial trials of vaccines to prevent HIV/AIDS in recent years, there is still no approved, warranted, and adequately supported vaccine for HIV/AIDS with clinical trial and reassuring research. Production samples are in the early stages of testing and trials, and they have a long way to go before obtaining final approvals and entering the market. An experimental RV 144 vaccine released in 2009 showed a slight reduction of approximately 30% in the risk of transmission, raising hopes in the research community that a vaccine could be effective (50). Further trials on the RV 144 vaccine are underway. Recently, the US CDC announced that Truvada, as one of the HIV prevention drugs, has successfully passed its trial stage (51). In its laboratory stages, this drug has been able to reduce the risk of HIV infection in people who were at risk of this virus by 92% (52). The best key prevention strategies for preventing AIDS include having sex within the family, not using condoms twice, having safe sex, not sharing needles, maintaining pregnancy health before trying to get pregnant, and not using needles from others (53). Education and information are considered the most important strategy for preventing AIDS (54). Achieving this goal requires social cohesion and targeted planning. Informing people about the harms and familiarizing them with the methods of transmission and prevention of HIV infection should be institutionalized among all ages and levels of society (55). The main ways of prevention of the HIV virus are explained in Figure 3.

3.6. Treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection

Currently, no effective HIV treatment or vaccine has been developed for this disease. Treatment includes antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which slows the progression of the disease. Since 2010, more than 6.6 million people in low- and middle-income countries have been diagnosed with this disease (56). In addition, the United States recommends this treatment for all HIV-infected individuals regardless of their CD4 count and symptoms, although it is less confident in recommending it to individuals with higher CD4 counts (57). It recommends this treatment for people with tuberculosis and chronic and active hepatitis B. It is recommended to continue this treatment without interruption or "break" once it is started. In many people, the disease is diagnosed when the ideal time to start the treatment is missed (58). The desired result of the treatment is that the number of HIV-RNA plasma is below 50 copies/mL over a long period. It is recommended that the levels that determine the effectiveness of the treatment be measured initially after four weeks, and when the levels reach below 50 copies/mL, it will usually be sufficient to control it once every three to six months (59). It seems that in ineffective control, something more than 400 copies per milliliter will be seen. Based on this criterion, treatment will be effective in more than 95% of people in the first year. The effectiveness of treatment depends largely on compliance. The reasons for non-compliance include limited access to medical care, lack of sufficient social support, mental illness, and substance abuse, as well as the complexity of treatment methods (due to the multitude of pills and doses) and their side effects, which may cause a person to become a voluntary non-citizen. Of course, in countries with low incomes, people are treated as well as in countries with high incomes. Specific side effects are related to the drug used, the most common of which are dystrophy syndrome, dyslipidemia, and diabetes that occur with protease inhibitors. Other common symptoms include diarrhea and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, although the side effects of some of the recently proposed treatments are less (60). The problem with some drugs may be that they are expensive. However, as of 2010, 47% of those requiring these drugs are from low- and middle-income countries. The United States recommends that children between one and five years of age be treated when their HIV RNA is greater than 100,000 copies per milliliter, and that children older than five years of age be treated when their CD4 count is lower than 500 per microliter. In 2014, researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark tried to use romidepsin to pull the HIV virus out of hiding when it is hiding from antiviral drugs and the immune system, to activate the hidden virus from the rest. This prevents the remaining hidden inactive viruses in the body during antiviral treatment (61).

3.7. Conclusions

In this narrative review, we considered the symptoms, ways of transmission, prevention, and treatment of the HIV virus. The results of this study showed that an increase in AIDS cases can seriously threaten the health of society, especially young people who play an important role in childbearing. Implementing policies and measures to increase public awareness, educating young people from elementary and high school levels about the disease and its complications, creating educational programs to help drug addicts quit, distributing syringes to injection drug addicts, increasing counseling clinics for AIDS patients, reducing the use of shared syringes, facilitating young marriages, covering the medications of infected patients, and following up on the condition of patients are among the things that can help reduce the prevalence and incidence of AIDS.